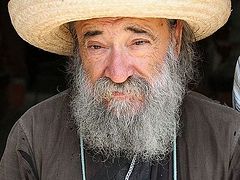

The father-confessor of Donskoy Monastery in Moscow and others share their memories of the newly-reposed elder, abbot of Dochariou Monastery on Holy Mount Athos, Schema-Archimandrite Gregory(Zumis).

Lessons to modern men

Alexander Artomonov, an acolyte, Moscow:

I remember coming to Dochariou Monastery one day, when the elder, as usual, was sitting there, surrounded by his beloved dogs. Russian and Ukrainian pilgrims were sitting around him as well, though somewhat farther off. The elder was talking with them. Suddenly he took his stick and struck one strapping fellow hard to his shoulders! “What is wrong, geronda?” the guy asked him, completely baffled.

“A man mustn’t wear women’s clothes,” the interpreter interpreted the elder’s words.

And that sturdy man had a gaudy shirt with palms on. That was totally unacceptable for the elder. He believed that men should dress modestly.

The elder’s gestures and speech were like those of a fool-for-Christ. And he used his stick so that his admonitions could stay in people’s memory.

Even if one had a red label on his shirt, the elder would immediately rush towards him to “educate” him with his staff…

“Communist!” he would exclaim. And one day I caught it from the elder for the way I dressed, too.

Once, when we (pilgrims) were sitting and talking to the elder, a priest took his camera and made a snapshot photo of geronda. At the same moment something unexpected happened. Fr. Gregory stood up, looking sadly at us, uttered something in Greek and left. We were at a loss. “What is up?” we asked the interpreter. “The geronda said, shaking his head: ‘Oh father, father! You won’t go to Paradise!’” Priestly ministry and the camera were seen by him as incompatible: if you serve in the altar, you shouldn’t care about external pomp anymore.

When I saw the geronda this spring, he was very weak. We dared not come up and receive his blessing because he looked so poorly. Young monks were guiding him, holding him by his arms, and he had great difficulty making every step.

And in the autumn, literally only a few days before his repose, I suddenly met the elder again, when I was boarding the ferry after a visit to Dochariou Monastery, while the elder was getting off the ferry by car. The elder looked so fit and cheerful, that I was unable to believe my own eyes! I even said to my companions: “Imagine that! The man who was dying not long ago is now enjoying good health again!” And all who were standing on the quay received his blessing with joy.

Scarcely had I returned to Moscow, when the news of Fr. Gregory’s repose struck me like a bolt from the blue! As is often the case, the Lord gave him a sudden burst of energy just before his end.

He craved for this energy so much! In the final years of his life the elder built about seven small churches along the seashore near the monastery.

I remember being absolutely amazed at seeing him at the head of a large procession, when he was already seriously sick. He was walking forward with determination. I inquired what he was doing and was told that the elder had just consecrated a new church. Although he was scarcely able to walk, he had blessed a newly-built church (constructed through his efforts and prayers) and served the first Liturgy in it. That was astonishing!

A very strict discipline was observed at the monastery under Fr. Gregory’s abbacy. Surely he inherited this strong spirit from his close relative, Elder Joseph the Hesychast. Confessors of other Athonite monasteries used to say when some young monk was doing something wrong: “We will send you to Dochariou Monastery for re-education!” At Dochariou the brethren labored very hard and their diet was frugal. It can be said that its community had simple, skimpy meals as compared with other Athonite monasteries.

People flocked to Dochariou Monastery not to rejoice in some material things and comfort, but to meet the elder—and it is amazing that one would meet him there every time! I would often go and think: “Will I meet the elder or not?” – And I would meet him each time without fail! The elder was already sitting and talking with pilgrims, or walking on the territory of the monastery (surrounded by dogs and cats), or working there in the open. And one could always receive his blessing.

While asking for his blessing, we saw his work-weary hands. At the sight of his hands we learned a lesson which is so useful for modern men. His hands literally preached hard work.

Elder Gregory was a man of holy life.

Fr. Gregory’s answer to Patriarch Bartholomew about Russians

Schema-Hieromonk Valentin (Gurevich), father-confessor of Moscow Donskoy Monastery:

After the beginning of perestroika some of my acquaintances, believing that it was time for them to do something to change the social climate for the better, were trying to take the first steps themselves. Thus, they sought counsel not only of Russian spiritual fathers of authority, but also of famous Athonite fathers.

I joined them on their trips to Mt. Athos on several occasions, though I later distanced myself from that group and became a monk of one of the capital’s monasteries.

One day the necessity arose for travelling to Mt. Athos to strengthen the faith of and instruct newly-converted neophytes there.

These were mature men who had gone through many ups and downs. They desperately needed instruction and exhortation to be provided by somebody on Holy Mount Athos.

For that visit I sought the advice of my secular friends mentioned above, who had established systematic contacts with Mt. Athos. They furnished me with a list of the names and addresses of Athonites of great authority.

And I decided to start our pilgrimage from Dochariou Monastery, as its abbot was referred to as an extraordinary and somewhat mysterious personality who was worthy of special attention.

According to a monk of Dochariou Monastery, who acted as a Greek-Russian interpreter during our communication with the elder (and even translated extracts from his conversations with Greek pilgrims for us), when we were approaching the monastery geronda made a remark about our impending arrival without seeing us:

“A Communist is coming…”

And in some sense the elder was right. Though by that time I had already become a monk, I was born into a Communist family, brought up as a Communist, and was a Pioneer and a Komsomol member in my teens. Fortunately, I never was a member of the Communist Party because I had been “enlightened” to some extent before then...

And my “leaven of Communism” had been revealed to the holy man before he saw me for the first time—a foreigner and perfect stranger to him!

The elder would often arrange talks with pilgrims at the monastery’s archondariki [a guest reception room].

While speaking to us, the elder stressed that just praying and avoiding physical work would be wrong for a monk and that monastics should perform manual labor for the benefit of everyone.

“What are your duties at the monastery?” he asked me right away.

There was an occurrence during my life in the monastery, when some journalists made a photo of me, then a bell-ringer, while I was ringing, and published this snapshot in a newspaper with the inscription, reading: “All go to the polls”. So I was demoted after that incident and became a monastery plumber.

But in the eyes of the elder I grew into a hero, and he even set me up as an example to the other pilgrims. Actually, I had worked as a plumber at Donskoy Monastery before receiving the monastic tonsure, and following the incident with the photograph the father-superior was reminded what else I could do without attracting the attention of the press… By all appearances, Fr. Gregory in his usual spirit of strict training approved all of this.

Fr. Gregory deemed it necessary for the spiritual health of monks, not least the young ones, in addition to long Athonite services to burden them with rather long labors that required considerable physical effort for subduing impure thoughts.

Permanent extensive building and repair work served this purpose, along with harvesting the ever-abundant olives and other fruit. Then olives were pressed by hand to produce olive oil, which was used not only to strengthen monks (after long-term exhausting work and obediences), but also as the source of oil for icon lamps and vigil lamps. There is no electric lighting at Dochariou Monastery.

Besides, some of the monastery’s olive oil was sent as a blessing to righteous Christians on the mainland Greece who preferred blessed oil to kerosene and electricity (which are widespread in Greece) for fueling their icon and vigil lamps.

It is remarkable that despite his permanent feebleness, physical pain, and a whole bunch of serious diseases, Fr. Gregory, who had no need of physical labors for his spiritual health (his maladies were more than enough), continually and selflessly worked with the brethren so that seeing his example the young monks might not be cast down or grumble about excessive “service of labor”…

Just imagine: One of my companions there, after performing obediences at Dochariou Monastery (in his former life he had been an athlete and robber) returned back home from Mt. Athos and worked alone for three years, constructing a two-storied stone house for someone who had nowhere to live.

He really loved to make mortar at Geronda Gregory’s, to get bricks and, most importantly, to join them together with the Jesus Prayer. He admitted that combining the Jesus Prayer with physical toil sobered him up and made him feel contrition.

We pilgrims would observe the novices; young Dochariou brethren labor there with great enthusiasm, thus “repairing” their own souls.

The elder, who every now and then behaved like a fool-for-Christ, was himself perhaps only in front of his monastery’s greatest relic—the wonderworking “Quick to Hear” icon of the Mother of God. He and his brethren always sang the canon loudly to it—with ardor, inspiration, and full dedication, like a child. It contained the names of all the archangels, movingly pronounced in Greek with soft “l”.

In spite of his eccentricity, even young drug addicts were brought to Fr. Gregory as to a caring mother for rehabilitation. We took one such teenager with us on that trip. He felt jaded and unstrung due to his drug dependence, shirked his work and skipped church services. But the elder, who often was stern with others, was very kind with this adolescent and took care of him.

Fr. Gregory was a person of whom it was said: A righteous man regardeth the life of his beast (Prov. 12:10). The elder ordered the brethren to see that all the dogs and cats living in the monastery were well fed in time every day. One male dog accompanied the abbot everywhere within the monastery, barking and sticking with its master.

Fr. Gregory, like his contemporary, St. Paisios the Hagiorite, was a patron of women monasticism. It is known that both of them founded convents: St. Paisios established that in Souroti, and Fr. Gregory founded one near Ouranoupoli. In this way they can be compared to Sts. Seraphim of Sarov and Ambrose of Optina in Russia, both of whom started and patronized communities for nuns.

By the way, the repose of Geronda Gregory coincided with the feast-day of St. Ambrose of Optina, who, like him, not only founded a convent, but was also afflicted with various painful diseases.

And female monasticism is especially significant in our days, when, in the words of Fyodor Dostoevsky, the dominant “ideal of Sodom” should be opposed by “the ideal of the Madonna”.

However, the elder strongly disapproved of the presence of women in monasteries. I recall how he asked me during our talk in the archondariki:

“Are there any women in your monastery?”

“Yes, geronda,” I answered.

“What are they doing there?!” the elder expressed his indignation.

“They keep the church clean, peel potatoes, cook, wash the dishes, work in the kitchen-garden, grow flowers in beds and vegetables in hotbeds,” I replied.

“Can you invite me to your monastery?” the geronda asked absolutely unexpectedly.

“Though I am not responsible for that, but please come to us! You will be very welcome!”

And then he announced the purpose of his supposed visit:

“I will kick all the women out of the monastery with this staff!!”

Then he addressed an honorable, fine-looking grey-haired elder of venerable age and his young cell-attendant from Romania, who were sitting near: “Are there women in your monastery?” And when they said no, he looked at me triumphantly and explained to me that communication with women is damaging to a monk’s soul and hinders his monastic life.

“As a young priest I used to draw back while hearing women’s confessions,” the elder shared his experience with me. “I would even turn away from them while covering their heads with my epitrachelion. They always tried to move up, while I moved aside.”

He proceeded to tell us about his childhood and youth. He grew up in a very pious family. His spiritual father was a renowned elder. When as a student he wanted to plunge into secular life and decided to begin with a visit to a cinema, his elder (who was many miles away) appeared to him in a vision on the same day and sternly forbade him to implement his “sinful intention”,, thus preventing him from deviating from the straight and narrow path. After that remarkable event the future elder never dared think about such things again.

As far as I remember, the elder in question who miraculously mended the future Geronda Gregory’s inclinations was Elder Philotheos (Zervakos; †1980).

I recall that in response to patriotic statements by some Greek pilgrims, who were concerned over the Turkish occupation of former Byzantine territories and asked when the Greeks would be able to win back Asia Minor, the elder replied:

“Don’t be bird brains! How will you attempt to make this happen?!”

He spoke about the moral degradation of the Hellenes who identify themselves as an Orthodox nation, the widespread sexual immorality, “birth control” in marriage, deploring that there were almost no young men in Greece fit for ordination to priesthood because in the Church of Greece a candidate to this ministry should be a virgin or the husband of one wife (so even monastic tonsure doesn’t guarantee ordination). By the way, Athens ranks first in the number of meetings arranged through dating websites.

Hence the slackness, degradation, and dying-out of the offspring of Orthodox Christians. Speaking with the elder, I found that I was of one mind with him. And, as my interpreter told me, the geronda even started citing to Greek pilgrims my aphorism about the idleness that has affected and paralyzed Orthodox people: “Women don’t want to be saved by childbirth anymore, husbands are unwilling to toil in the sweat of their brow, and monks don’t take the trouble to pray hard.” And this corruption and slackness have led to a decrease of fighting capacity, which the Greeks would need if they were to win back Asia Minor…

But does it make sense to put it this way? Is there a need to revive the greatness and might of the “Orthodox empire” by another bloodbath? Maybe the so-called “Byzantine lesson” was an instrument by which God trampled down proud “Orthodox nations”, as was the case with the seventy-year Babylonian Captivity in the Old Testament and the seventy-year “atheistic captivity” of Russia in the twentieth century? And what about the fulfilled prophecy of God incarnate about the beautiful buildings of Jerusalem: There shall not be left one stone upon another (Mark 13:2)? And this was said in response to the chosen people’s vainglorious aspirations as they were expecting Christ to sit on David’s throne in Jerusalem…

These words are as clear as daylight: My Kingdom is not of this world (Jn. 18:36). And every time, contrary to the plain truth of the Holy Gospel, various ethnic groups have made the same mistake over and over again, endeavoring to make their vicious dream (exposed and rejected by God Himself) a reality, namely to build a mighty and powerful earthly “Orthodox” state (or a kingdom, or an empire), which will be able to “set the world aright”…

All of my companions grew very fond of Geronda Gregory, the community gathered by him, and Dochariou Monastery. The monastery’s brethren consisted of absolutely different people, from highly educated academicians to simple elders.

For example, there was an interesting old man named Charalampias there. He was short, lean and worked diligently. Fr. Gregory would tease him in a good-humored manner. As soon as somebody entered the monastery gate, he would rush to their assistance, explaining to them what was the proper order in which to venerate icons, how to receive a blessing from a priest, and so forth. And he did it fussily and comically. Observing this little old man made us laugh. And it was obvious that despite his age the man didn’t give up his spiritual labors and fervent prayer. Fr. Gregory praised him for that with a certain degree of irony. All of this made the atmosphere of Dochariou Monastery at the time of my stay there very unique.

Incidentally, monks of Dochariou Monastery were always interested in the spiritual life in Russia, specifically in how we managed to preserve the continuity of tradition. I told them about our holy elders, how they had gone through exiles and labor camps and prayed there under the harshest conditions. I cited Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) as an example of an elder who had a healing effect on people. The Dochariou brethren would listen to me attentively.

I recollect that one pilgrim at Dochariou told us the following about Elder Gregory: Once during the Eucharistic canon he (the pilgrim) felt as if some powerful wave had surged up and lifted all those inside the church up to a height that had previously been unattainable for them. He admitted he had never felt such a powerful energy in the celebration of the Eucharist as this one with Fr. Gregory.

Dochariou Monastery enjoyed wide popularity with pilgrims from the Patriarchate of Moscow. A high percentage of Dochariou monks have always been Russian. Patriarch Bartholomew reproached and reprimanded the abbot for this more than once. This is how the elder would answer him:

“I can’t do anything with this. It is the Theotokos Who has been sending them [Russian monks] to me.”

Not long ago a video entitled, “A Paschal Word to the Ukrainian People” was posted on the internet. In it Geronda Gregory answers a question about the Ukrainian crisis (the translation from Greek):

“I, humble monk of Holy Mount Athos, would like to say a word to the much-suffering Ukrainian people and all the Russian people in general: forgive each other and move together with love towards the great feast of Pascha. If we bear a grudge against our brothers, we cannot celebrate Pascha. Forgiveness shone forth from the tomb of Christ. Only he who forgives and loves his brother will be able to celebrate Pascha. Thus all the nations will know that we are true disciples of Christ. According to the teaching of St. John Theologian, as he wrote in the Holy Gospel: By this shall all men know that ye are My disciples, if ye have love one to another (Jn. 13:35). Christ Is Risen!”

The unhealthy climate in Ukraine and Russia caused great distress to Elder Gregory. He prayed a lot for our people. When asked about the enemies of Orthodoxy, he would reply:

“True, these are real enemies. But if we hate them, we won’t go to Paradise.”

It should be said that at the beginning of my pilgrimage trip with the neophytes we intended to visit other monasteries of Mt. Athos after Dochariou and meet other wonderful Athonite fathers.

But when Dochariou Monastery suggested an alternative to us, namely spending the entire pilgrimage trip in this “monastery of the archangels”, we agreed. In this case we could focus on one example of genuine Athonite monasticism to get a deeper understanding of its essence, which we otherwise would not have so strongly felt after brief meetings with many abbots.

And I don’t think we should regret the choice we made as it has borne fruit.

Why both simple and high-ranking people sought to get into these “military barracks”

Gregory Gorokhovsky, a reserve officer, St. Petersburg:

What really astonished me in Geronda Gregory was the remarkable accuracy of his description of every single visitor, whether it be a young Greek man or our Russian monk. He “X-rayed” all of his guests, seeing them inside out, and could denounce any of them in the presence of everybody.

After the morning service the elder would arrange talks for pilgrims. And guess what amazed us the most? There were quite big rooms for pilgrims at the monastery that could accommodate up to fifteen persons. We, robust men, would gather in the evening and discuss various spiritual themes and the things that were hard to fathom. And the next morning, when we gathered at Fr. Gregory’s, like school students, he would begin enlightening us and explaining to us all the things in order, answering every single question we had mentioned the previous night…

Day in and day out we would listen to him attentively with downcast eyes, and one morning after another “final review” we dashed into the cell, trying to find some listening devices behind the icons!... Needless to say, our search was in vain. There was no electricity in the monastery, not to mention “bugs”! Moreover, the monastery was huge, and devising any more primitive methods of bugging was impossible either. After all, not only did the elder answer our questions, he also thoroughly commented on other unsettled questions we discussed in other cells...

All of this made us tremble.

The work schedule at Dochariou Monastery was extremely heavy. Nobody had time for rest there. Even those who held the highest ranks worked shoulder to shoulder with us as hard as any of us. They would come here to spend their vacations at Dochariou Monastery instead of five-star hotels and luxury resorts. From morning to late night we would “keep our noses to the grindstone”, as it were. In some sense it resembled military barracks. It was like a harsh boot camp—the geronda was remolding us, lock, stock, and barrel. We would even miss evening services. The elder was with us all the time.

I recall how one day we were picking up stones for the masonry of a new wall. Some were doing it on the shore, others somewhere on the slopes, others were carrying them up, others were mixing cement, others were making masonry. I remember dragging a huge block, when the elder started shouting at me. He was running side by side and yelling at the top of his voice. “I’ve been caught! The elder has ‘X-rayed’ one of my thoughts and is now exposing me!” I thought. The elder was scolding me in Greek, but I didn’t know a word of that language. Meanwhile I was lugging this block without stopping. And suddenly I strained my back, so one of my vertebrae was even pushed out. While the elder looked at me sadly… Only then did the interpreters explain to me that the elder had shouted to me: “Why are you dragging it?! You will break your back now!”

The geronda was usually hard on people. But when he opened up his soul to us and by the grace of God we were able to contemplate this unearthly purity (even if for a moment), these were unforgettable moments.

Fr. Gregory has left an indelible mark on my soul and indeed on the souls of many others.

Eternal memory! May he rest in heaven!