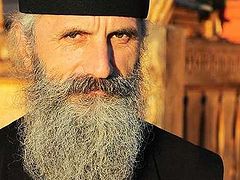

Archimandrite George (Yevdachev), Abbot of St. George’s Monastery of Meshchovsk in Russia’s Kaluga region[1], talks about Divine providence in his life.

The monastery twenty years ago and today

St. George’s Monastery in Meshchovsk

St. George’s Monastery in Meshchovsk

We were visiting St. George’s Monastery in Meshchovsk. Admiring this stunning monastery, its beautiful church and numerous relics inside it, we could hardly imagine that Archimandrite George (Yevdachev), the monastery’s abbot, began its restoration from scratch.

When Fr. George came here twenty years ago, he saw nothing but lonely shells of ruined churches dominating an open field, and the first community of monks often didn’t have enough money for food.

The monastery in the years of desolation

The monastery in the years of desolation

In our days many pilgrims go to this monastery to receive spiritual guidance, and their children can enjoy the company of numerous monastery pets: peacocks and ostriches, deer and yaks, squirrels and various species of birds. And no wonder—the monastery abbot once graduated from the K.I. Skryabin Moscow State Academy of Veterinary Medicine and Biotechnology. There are also more common animals, such as cows and chickens, so the monastery monks and guests can regale themselves with homemade dairy products and eggs on non-fast days.

We were given a cordial welcome. Archimandrite George himself fried potatoes for us, and indeed the potatoes were excellent. According to the brethren, the “father” (this is how they call Archimandrite George) also cooks delicious Russian borscht. After lunch the monks dispersed to their work, while we listened to the father-superior’s story.

Archimandrite George with the fried potatoes he made for his guests

Archimandrite George with the fried potatoes he made for his guests

Divine providence

Looking back at the past years, I clearly see Divine providence guiding me in my life path thanks to which I ended up here—at St. George’s Monastery in Meshchovsk.

By the light of a kerosene lamp

I grew up in a very religious family, and all the residents of our Zhilino village [now the town of Kirov.—Auth.] were believers. It was the only village in the Kaluga region to reject collectivization. That accounts for the fact that the authorities didn’t like our residents, and our village received no electricity until 1965 (the year of my birth), though Zhilino was just two miles away from the district center.

I recall that when I was a first-grader electricity was often disconnected in our village, and our nanny (my mother’s aunt) often used a kerosene lamp. We used to take vials of ink to school and write with fountain pens at lessons, though it was in the 1970s.

How I learned to read

I am the oldest son in the family (there are three of us siblings). I learned to read Church Slavonic earlier than Russian. Our nanny brought us up.

“Son, please look what day is the feast of Sts. Cyrikos and Julitta this year?”

“Nanny, I have no idea!”

“Go and fetch the Psalter with the calendar!”

“Here you are.”

“Now read!”

“But I can’t!”

“Look, these are the letters…”

And I learned to read the Psalter very soon. In our village they read it using poglasitsa (traditional melody), a kind of recitative reading to a particular traditional melody.

We didn’t do anything without prayer

All the inhabitants of our village lived strict lives filled with prayer—women even prayed in their headscarves at home, sent the cattle to grass with prayer, sowed and plowed with prayer—we didn’t do anything without prayer. We kept all the fasts very strictly.

We treated the departed with great reverence and felt our responsibility for them. They could no longer pray for themselves and help themselves and waited for the prayers of the living.

Once I was warned at school:

“You may not wear a cross.”

Then my mother went to the school and said resolutely:

“I entrusted my child to you so that you could give him education. As for his religious faith, that is my right.”

The Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos at the cemetery

The Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos at the cemetery

The only church that we had was the Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos at the cemetery of Kirov. This church was surrounded by police patrols to deny access to young people. But our nanny would hide us children under her skirts and secretly ride to the church on a cart. When I grew up a little, I walked to church on my own—four miles there and back altogether.

My dreams

After leaving the eighth grade my classmates (boys) opted for a specialized education at vocational schools, while I wanted to complete my secondary school education. Then I made grandiose plans—I wished to live close to the earth and with the faith. My dream was to own a big farm—to have a lot of land rich in harvest. My dream was to open a church, a school and a home for the poor there and help the sick as a doctor.

It can be said that my dreams have come true: Our monastery has land, crops, a farm of its own; we have restored churches and children come to us. If you walk around our monastery, you will see different birds and other animals—they feel comfortable and there is space for all of them, glory to God! As a veterinarian I can treat them and even perform operations.

Back to my school years. Only twelve girls and I remained in the class after the eighth grade. They got accustomed to me and even forgot that a boy was near them and sometimes indulged in their girlish conversations in my presence. My favorite subjects at school were chemistry and biology.

We became such close friends that I went with the girls to study at the Milk Academy in the Tver region. I learned to be a head cheese maker and graduated with distinction, then worked at a cheese factory. And I was always with God and never abandoned prayer.

“Be a good soldier!”

I was conscripted into the army. I recall how my father exhorted me: “If you have to die for your motherland, then die. Be a good soldier. There were partisans in our family [during the Second World War.—Trans.]. Father’s uncle was named George—the Nazis hanged him right on a well-sweep before all the villagers’ very eyes. Keep that in mind. Don’t bring disgrace on our family!”

I served in the artillery. First I was in a training unit (for young conscripts) in Nizhny Novgorod, and later as a junior sergeant I was sent to Perleberg in Germany. I was in an antitank battery, where I was appointed commander of a fighting reconnaissance patrol machine. I was an excellent athlete and moving spirit. My faith helped me and never obstructed me.

On a collective farm

I returned home as a senior sergeant. I made up my mind to enter an institution of higher education. It should be said that I was very fond of animals; as a boy I used to keep crows, pigeons, siskins, rabbits, and even hedgehogs. When I was about to join the Moscow State Academy of Veterinary Medicine, the selection committee told me:

“It is very difficult to join our Academy. There are usually seven applicants for every seat here. You’d better work on a collective farm for a while for a start.”

At a collective farm’s threshing floor

At a collective farm’s threshing floor

For a year I worked on a collective farm in the Kaluga region as a threshing-floor and animal feed production foreman. For weekends I would come back to my parents’ home in my native village, where I was dead on my feet.

“What has happened, my dear son?”

“Mom, it is so hard for me to see others drink home-distilled vodka and work negligently, and listen to obscenities all the time...”

The beloved church

A year later I entered the Academy. I went to study in Moscow, taking a three-liter jar of sauerkraut, a large piece of salo [food consisting of salted or cured fat from pork back or abdomen in Russia and Ukraine.—Trans.], and fifteen rubles with me.

When I attended church in my native village, I could feel that the authorities were displeased. But in Moscow I had freedom, no one spied on me, and I could attend any church I liked. And right from the platform of the Moscow Belorussky Railway Terminal I hurried to the nearby Church of the Deposition of the Robe of the Theotokos on Donskaya Street (my relatives lived close by). The funeral service for Blessed Matrona of Moscow was conducted in this very church.

The Church of the Deposition of the Robe of the Virgin Mary on Donskaya Street

The Church of the Deposition of the Robe of the Virgin Mary on Donskaya Street

When I went up, the church was locked because someone inside was tidying it up.

“May I just cross the threshold and stand for a couple of minutes?”

“Well, you may.”

I entered the church narthex (vestibule) and was beside myself with delight. I could not breathe enough of the church air. On the south wall of the church I saw the much-venerated image of the Mother of God, “The Seeker of the Lost”—a wall painting which was famous for many miracles and cures.

And thus I came to love this church!

Prayers to the Theotokos

I began to attend the Church of the Deposition of the Robe frequently and pray in front of the icon, “The Seeker of the Lost” this way:

“O All-Holy Mother of God, save the servant of God Gennady (my secular name) who is weighed down with sins.”

The Church of the Deposition of the Robe of the Mother of God

The Church of the Deposition of the Robe of the Mother of God

And then I would pray to the Kaluga icon of the Theotokos:

“O Queen of Heaven, You are the Mistress of our region. Please, guide me under Your protection!”

The Kaluga icon of the Mother of God

The Kaluga icon of the Mother of God

And my prayer was answered: the Protectress of the Kaluga region led me to the land of Kaluga…

“Doctor Gen is praying”

My studies at the Academy began. So I was going to move into dorm. I saw that the door of one room was wide open and there were around fifteen Africans inside—I thought they were visiting someone. “I hope I won’t have to share the room with them, I am awkward with foreigners,” I thought. But I was told to move precisely to that room! One of my roommates was from Zambia, another one—from Nigeria; the former was a Protestant, the latter a Catholic.

I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to pray in their presence. After all, they could potentially squeal on me: the Church was still persecuted, and religious students were expelled. At first I was overcautious: I would open an anatomy textbook, putting my prayer-book on it. As I prayed, they didn’t react. Then I began to pray and make the sign of the cross openly. But they didn’t react again. Next I began to pray properly: while standing and making bows. All was quiet. Then I grew bolder: I brought icons with rushniks [embroidered handmade towels.—Trans.] and started to pray in front of them. But my roommates had even more respect for me.

Whenever someone knocked at the door, they would say:

“Don’t come in now, Doctor Gen is praying!”

And they didn’t let anybody in as long as I was praying.

A jar of cucumbers and a jar of sauerkraut

As usual, I kept all the fasts. Fellow-students began to come to me and ask me questions about the faith. Many of them decided to keep the fasts too and join me for church services. Now some of them even serve as priests.

The teachers noticed that we observed the fasts. The teacher Raisa Vasilyevna asked us during a seminar:

“Are you fasting now?”

“Yes, we are.”

“Take a jar of cucumbers and a jar of sauerkraut to fortify yourselves.”

A sticharion for the new altar server

So I studied at the Academy and attended my favorite Church of the Deposition of the Robe of the Theotokos—I didn’t miss a single service. One day, when I was praying at the service, the rector, Archpriest Vasily Svidenyuk of blessed memory († 2011), invited me into the altar. The acolyte extended the invitation to me, but I felt shy:

“I am a sinner, how can I enter the altar?!”

During the next service I was invited to the sanctuary again. When I finally stepped into the altar, I was scared to breathe: I felt as if I were in heaven.

The rector said:

“Give the new altar server a sticharion.”

How I felt a desire to become a monk

In 1991, shortly before I graduated from the Academy, the relics of Venerable Seraphim of Sarov were discovered and placed at the Theophany Cathedral at Yelokhovo, Moscow. When I arrived, I saw a multitude of people there. The faithful had been denied access to holy relics for many years, and people got out of the habit of venerating them.

When the faithful were venerating St. Seraphim’s skufia [a low hat worn by Orthodox monks.—Trans.], I had a terrible temptation: I suddenly remembered some information from virology. And I resolved that while everybody was venerating the skufia, I would kiss his bodily relics to chase away the temptation (his skull was partly seen from beneath the skufia).

The meeting of the relics of St. Seraphim of Sarov

The meeting of the relics of St. Seraphim of Sarov

Once I had venerated his relics with prayer, all doubt fell away. And I had only one thought in my mind: “Why did I study at the academy for five and a half years if I need nothing more than to be near St. Seraphim? I wish I could drop a mat on the floor by his feet and stay here forever, just live and pray near his relics without going anywhere. There is such abundant grace here…” I felt the desire to become a monk, and nothing attracted me in the world anymore.

“You will be both a monk and a priest!”

When I revealed my desire to the rector of my favorite church, he blessed me to go to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra for a few days to pray and work a little and take advice from Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) regarding my path in life. I went to the Lavra where I lived, prayed and worked for a while. And my desire to stay there and take up monasticism grew so strong that I neither needed any Academy nor bothered about the state exams anymore.

In those years hundreds of people would flock to Fr. Kirill, and seminarians would form a human chain to “shield” the elder from the crowd and help him get into church for the service. And while the seminarians were standing in a row and the elder was walking towards the church, I cried from the top of my voice, addressing him:

“Father, father! I am here to speak with you!”

I was standing and shouting like crazy. And the elder walked past as if ignoring me. Then he stopped, looked downward, and then lifted his eyes to me, while I was beating my breast and yelling:

“Father, it was me who called you! I am here to see you! I want to become a monk and a priest!”

And he raised his hand, blessed me and said loudly:

“You will be both a monk and a priest!”

A spiritual father

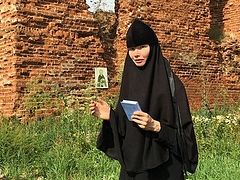

Soon a spiritual son of Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov), Archimandrite Platon (Panchenko) from the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, became my spiritual father. Now he serves as father-confessor of the Metochion of the Estonian Holy Dormition Pukhtitsa Stavropegic Convent in Moscow.

Archimandrite Platon (Panchenko)

Archimandrite Platon (Panchenko)

I saw that Fr. Platon lived in two realms—the earthly and the heavenly—at the same time, and walked before God. This is what I learned later: Every morning before performing his obediences he would go to the relics of St. Sergius of Radonezh and whisper:

“Father Sergius, give me your blessing for today’s obedience!”

And at the end of the day he would come to the relics again and say:

“Thank you, our Venerable Father Sergius! I have done well today!”

“How could I burden myself with such an overwhelming load?!”

Metropolitan Clement (Kapalin)

Metropolitan Clement (Kapalin)

Meanwhile, the Academy state exams were coming, we were given some time for preparation, and I went home for a short time. On my way back a priest from Kirov gave me a lift to Kaluga. While in Kaluga, he suggested that I call on Archbishop (now metropolitan) Clement of Kaluga and Borovsk and ask for his blessing. The hierarch blessed me and said:

“Find me at St. Daniel’s Monastery in Moscow. I would like to speak to you.”

It was at that time that the restoration of the churches that lay in ruins began. There was an acute shortage of priests in Russia, and there were very few monks.

When I came to the archbishop, he advised me to follow the path of the Church I had chosen. My spiritual father gave me his blessing, and soon I was ordained a deacon. And I even didn’t know how to burn incense. I thought: “How should I burn incense?”

It was also difficult for me to celebrate church services; I wept so much that my first cassock fell to pieces from tears and sweat. I also thought: “How could I burden myself with such an overwhelming load?!”

I went to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, where my spiritual father’s prayers strengthened me, and I memorized all that I was supposed to do as a deacon automatically.

Later I was ordained a priest at St. George’s Cathedral of the city of Kaluga, and I felt that the Greatmartyr George the Victorious took me under his wing. Then I was assigned to a parish in Kondrovo [a town in the Kaluga region on the River Shanya.—Trans.], and later served in Obninsk [the “science city” of the Kaluga region, home to the world’s first nuclear power plant.—Trans.].

In honor of the Venerable Confessor George (Lavrov)

The Venerable Confessor George (Lavrov)

The Venerable Confessor George (Lavrov)

I was tonsured at St. Tikhon’s Hermitage Monastery in Kaluga. When Archbishop Clement was going to tonsure me, he came to St. Tikhon’s Hermitage Monastery, where he was met by Archimandrite Tikhon (Zavyalov). Fr. Tikhon showed him a new book and said:

“Your Eminence, look! A book on our New Confessor of Kaluga, George (Lavrov), Abbot of Meshchovsk Monastery, has been published.”

It was perhaps for this reason that Archbishop Clement tonsured me a hieromonk in honor of the Venerable Confessor George (Lavrov) [† 1932; his relics are venerated at St. Daniel’s Monastery in Moscow.—Trans.]. After the ceremony the archbishop gave me the following instruction:

“Now that you bear the name of the Meshchovsk Monastery’s abbot, you should go and restore that monastery.”

This is how St. George’s Meshchovsk Monastery looked like when it was desolate

This is how St. George’s Meshchovsk Monastery looked like when it was desolate

I answered:

“Your Eminence, give me your blessing!”

And I went to Meshchovsk where I have been the abbot of St. George’s Monastery for twenty years.