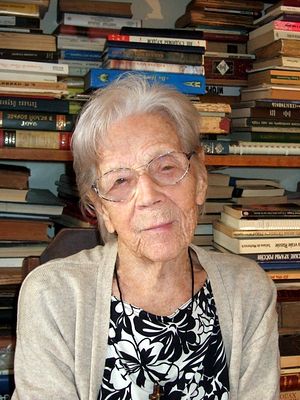

“I had long been waiting for Russian citizenship and didn’t want the Soviet one. Then I waited for a passport with a double-headed eagle, not accepting the one with the ‘International’ emblem. And I was granted it at last—what a stubborn old woman I am!” September 5, 2019, marked the 107th birthday of an extraordinary woman—Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya.

Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya was born on August 23/September 5, 1912. As was the case with many other children, during the Civil War as a little girl of eight she was evacuated from Russia to Tunisia. A terrible thing about the Civil War was that it was not fought against an enemy who invaded the country: people fought with their own relatives, brothers, who spoke the same language, lived in the same land, and in many cases—even in the same families. But the most terrible thing was the fact that out of ten million casualties only 800,000 were soldiers and officers, while the other 9.2 million were civilians: children, women, and old people.

Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya was born on August 23/September 5, 1912. As was the case with many other children, during the Civil War as a little girl of eight she was evacuated from Russia to Tunisia. A terrible thing about the Civil War was that it was not fought against an enemy who invaded the country: people fought with their own relatives, brothers, who spoke the same language, lived in the same land, and in many cases—even in the same families. But the most terrible thing was the fact that out of ten million casualties only 800,000 were soldiers and officers, while the other 9.2 million were civilians: children, women, and old people.

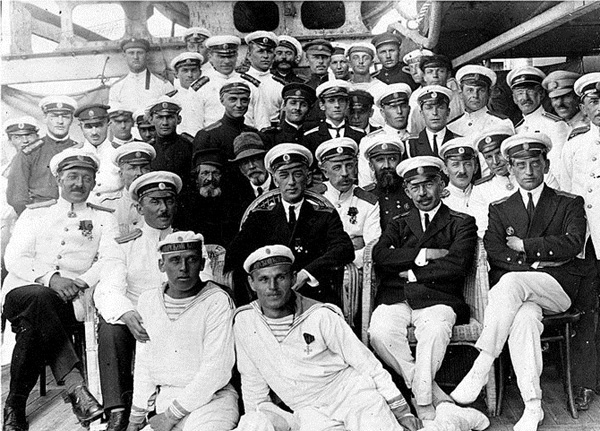

Anastasia’s father, Alexander Manstein, was a naval officer and commanded the “Zharky” (“Hot”) torpedo-boat destroyer. In November 1920, thirty-three ships were leaving Russia forever: first they moved to the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey (where the land forces of Baron Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel’s army remained), and then to the Tunisian city of Bizerte. Alexander Manstein said to the sailors: “We have taken the spirit of Russia with us. Now Russia will be here.” And those words had a very deep meaning because these people truly managed to “take” Russia with them in their hearts and on their vessels. Remarkably, on their way to Bizerte a violent storm broke out, and the “Zharky” destroyer’s rope on which it was being towed came untied several times because of an error. The sailors and their families were urgently moved to another ship. Then the old boatswain Bogdan Chmel tied an icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker to the destroyer. “Kronstadt” moved ahead, towing “Zharky” with the icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. And by a Divine miracle (since the vessel without the sailors on board was absolutely out of control) it was successfully towed as far as Bizerte.

Russian squadron ships in Bizerte

Russian squadron ships in Bizerte

In Bizerte the sailors continued their customary way of life: maneuvers were conducted continually, and the sailors practiced underwater swimming. More than 6,000 people arrived in all, with professors, doctors and priests among them. Bridges were built between the decks because the sailors and their families were not allowed to go ashore for almost four years. The vessels were surrounded by small yellow buoys, and small “apartments” were set up: some lived astern, others lived on decks. Lectures were read, plays were performed, children knew all the Orthodox Church festivals, baked kulichi [traditional Pascha breads—Trans.] for Pascha, and were taught a whole classical school curriculum. The sailors raised their children in Orthodoxy and instilled love for the history of their motherland in them.

A naval cadet corps was formed on the “General Kornilov” cruiser; there were an Orthodox church, a school, and even overhaul shops on the “Kronstadt” cruiser, which was later confiscated by the French authorities because of the plague that had mysteriously broken out there. The cruiser was sailed off to France where a month later it was renamed “Le Volcan”, with the French flag flying over it. The Russian sailors were robbed and deprived of the basics of life. By the way, there had even been an operating room on one of the ships! It was in this environment that little Anastasia Manstein lived and was raised. When France recognized the Soviet State, all the Russians were offered French citizenship. Anastasia Alexandrovna’s father used to say that the Russian officers only swore allegiance once—and since they had already once sworn allegiance to the Tsar, they remained faithful to that oath, to Imperial Russia.

Those who refused to get French citizenship lost their jobs. Women did the washing, sewing and darning. Anastasia Alexandrovna’s mother, Zoe Nikolaevna Doronina, used to say that she was not ashamed to wash clothes but she was ashamed to do it badly. And, while washing clothes, she would sing songs about her motherland. She wanted all of her three daughters to be well-educated and become good people.

Like many other families, the Mansteins refused to become French citizens. Until 1997 Anastasia had lived with a passport of a Russian refugee, a Nansen passport [a document of identification issued to stateless people after the First World War.—Trans.], on which it was written that she had a right to travel to any country except the USSR. And Anastasia had been waiting for a Russian passport with a double-headed eagle her entire life: “I had long been waiting for Russian citizenship and didn’t want the Soviet one. Then I waited for a passport with a double-headed eagle without taking that with the “Internationale” emblem. And I was granted it at last—what a stubborn old woman I am!” But many didn’t live long enough to receive any of this; among them were Anastasia Alexandrovna’s parents along with Michael Andreevich Berens, the last Rear Admiral of the Black Sea Fleet. Berens, who sewed leather bags in the final years of his life, died in extreme poverty, though large amounts of money had once run through his hands.

Officers and sailors of the Bizerte squadron

Officers and sailors of the Bizerte squadron

Anastasia Alexandrovna was granted Russian citizenship on the feast of the Holy Royal Martyrs. And it was symbolic. She remained faithful to Russia, and Tsar Nicholas II accepted this loyalty. One of her students was Bertrand Delanoë, Mayor of Paris between 2001 and 2014, and she was on friendly terms with his family. Whenever Delanoë visited Bizerte, he would call on his former teacher. Once, while visiting St. Petersburg, he called Anastasia Alexandrovna and said that he had seen the St. Andrew’s Flag on some Russian ships. And she remembered the tragic end of the Russian squadron, when in October 1924 the St. Andrew’s Flags were lowered, and the ships handed over to the French Government. The Maritime Prefect in Bizerte Vice-Admiral Exelmans was informed that the day before France had officially recognized the Soviet Union. Receiving the telegram that obliged him to start the liquidation of the squadron, Vice-Admiral Exelmans gathered Russian officers and naval cadets at the “Derzky” (“Bold”) torpedo boat to share the distressing news with them. This is how Senior Lieutenant Monastyrev described that meeting:

“The old admiral was very disturbed, and his eyes filled with tears several times. A worthy seaman, he was sympathetic towards us and shared in our grief. But the officer’s duty made him execute the order: We were to leave the ships… And we left.”

On the same day, at 5:25 p.m., October 29, the St. Andrew’s Flag was lowered. And for her, the daughter of a naval officer, it was a great blessing and grace of God to live to see the time when the St. Andrew’s Flag would once more fly over the Russian Navy. The Lord vouchsafed her to see this with her own eyes.

Anastasia Alexandrovna remained of perfectly sound mind till the end of her life.

She taught mathematics all her life: from the age of sixteen when she was still a student herself. She would say: “Study mathematics, it will help you preserve your mind.” Her daughters, who are physicists, live in France. She would say to them that only the hard sciences could save them from poverty.

Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya at the Russian cemetery of Bizerte

Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya at the Russian cemetery of Bizerte

The Church of the Holy and Right-Believing Prince Alexander Nevsky was built in Bizerte in 1932 in memory of the Russian squadron, its sailors, officers, and admirals. The katapetasma [the curtain inside the altar behind the Royal Doors in Orthodox churches.—Trans.] of this church is the same St. Andrew’s Flags that were lowered in 1924. The church has a marble slab with the names of all the ships that came to Bizerte. It also has a casket with some earth from Sevastopol. And there are St. George’s Crosses on the church gate.

It seems to us that today Russia is reviving largely thanks to the sacrifices and heroism of the people who managed to retain their humanity and not become hardened in the Civil War.

Anastasia Alexandrovna was often asked why she still loved Russia, a country which had caused so much harm to her and her family. And she would answer that Russia hadn’t done anything wrong, but the people who had taken power and destroyed Russia were to blame. When she was saying these words, there was no hatred for those people in her voice. It was just a statement of fact: Since God allowed all of this, there was a reason for it.

Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya at the Russian cemetery of Bizerte The church was built with the modest funds of the Russian officers, but Tunisian Muslims helped too. According to Anastasia Alexandrovna, at first only a prayer room was set up in a leased building, and there was no charge for the rent because taking money for prayer to God was considered a sin. By the 1960s there were almost no Russians left, there were no means to support the priest’s family, and services were not held in the church for a long period of thirty years. To prevent the closure of the church Anastasia Alexandrovna with her friends (there were Muslims and Catholics among them) just went into the church regularly so that people could see that the church was needed. Anastasia Alexandrovna stored up all the values she had been raised with and the qualities her soul was filled with. And she lived to see the 1990s, when the Patriarchate of Moscow sent a Russian priest to Tunisia. It was largely through her prayers that the Church of the Holy Prince Alexander was not demolished.

Anastasia Alexandrovna Manstein-Shirinskaya at the Russian cemetery of Bizerte The church was built with the modest funds of the Russian officers, but Tunisian Muslims helped too. According to Anastasia Alexandrovna, at first only a prayer room was set up in a leased building, and there was no charge for the rent because taking money for prayer to God was considered a sin. By the 1960s there were almost no Russians left, there were no means to support the priest’s family, and services were not held in the church for a long period of thirty years. To prevent the closure of the church Anastasia Alexandrovna with her friends (there were Muslims and Catholics among them) just went into the church regularly so that people could see that the church was needed. Anastasia Alexandrovna stored up all the values she had been raised with and the qualities her soul was filled with. And she lived to see the 1990s, when the Patriarchate of Moscow sent a Russian priest to Tunisia. It was largely through her prayers that the Church of the Holy Prince Alexander was not demolished.

Incidentally, the square in which the church stands was named after Anastasia Alexandrovna, when she was still alive.

It was the Tunisian residents that gave the square this name. She was awarded the Tunisian State Order of Companion of Culture.

Virtually all the city residents knew Anastasia Alexandrovna, calling her “Babu”, or “Madame Shirinsky”. As the only surviving Russian woman in Bizerte she used her slender means to maintain the graves of Russian sailors and look after the monument to Russian and Soviet sailors (there had been a concentration camp in Tunisia during the Nazi occupation).

In 2004, the Russian Orthodox Church conferred the Order of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Princess Olga on Anastasia Alexandrovna; and she received a special award “For Labor and Fatherland” of the Russian National Literary St. Alexander Nevsky Prize.

In 2004, the Russian Orthodox Church conferred the Order of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Princess Olga on Anastasia Alexandrovna; and she received a special award “For Labor and Fatherland” of the Russian National Literary St. Alexander Nevsky Prize.

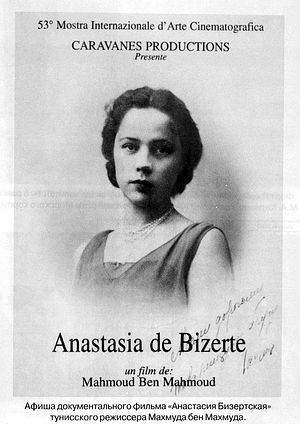

In 2006, Anastasia Alexandrovna was stricken with a severe illness and went into a coma. But, according to the woman herself, the Lord restored her to life so that she could share her memories and thus make an invaluable contribution to the documentary by Nikolai Sologubovsky and Victor Lisakovich, “Anastasia. The Angel of the Russian Squadron”. The film received many honorary awards, including a prize of the “Kinotavr”, Russia’s largest film festival. Anastasia Alexandrovna, the chief female character, lived to see its premiere and waited for it to be shown in Russia. The documentary was shown on Channel One in Russia in February 2010.

Unfortunately, Anastasia Alexandrovna had reposed earlier—on December 21, 2009. Her whole life, like the lives of her parents and other people who had lost their names, homes, and motherland, was a feat of faithfulness to Russia, the Russian Church, and God.