In 1917 began what would become perhaps the most complex period in the history of the Russian Church. In great measure thanks to St. Tikhon, his dedication to his service, and his personal martyric podvig, the Church survived that era. It was literally “carried on the shoulders” of the holy patriarch from the flames of persecution and social turmoil.

The history of His Holiness’s lineage is hidden in his surname

Before monasticism, St. Tikhon was named Vasily. His surname, Bellavin, was a fairly common name in the Pskov governate, where he was born. The future Patriarch came from a priestly family. According to a tradition in the Pskov governate, strictly only people of a spiritual vocation could be surnamed Bellavin. Some suppose that it proceeded from the name, “bely” (white), which was associated with purity and incorruption. This surname bespoke the family’s piety.

Incidentally, there is some confusion in the spelling of Patriarch Tikhon’s last name. It is connected with the fact that the soviet press in the 1920s systematically deleted one letter “l” from his name. This mistake crept into many other articles and publications. The correct spelling of His Holiness’s surname is really “Bellavin”.

Even in his school years, his classmates would jokingly call out to Vasily, “Your Holiness, many years!”

The Pskov theological seminary, where Vasily Bellavin studied and taught. Photo from the early twentieth century.

The Pskov theological seminary, where Vasily Bellavin studied and taught. Photo from the early twentieth century.

At age nine, Vasily began attending the Toropets church school. His classmates, knowing the future saint’s peace-loving and gentle nature, once put together a censer from some scraps of metal and swung it, solemnly shouting to him, “Your Holiness, many years!”

In the Pskov theological seminary Vasily was nicknamed “Hierarch”, and in the Petersburg theological academy they would call him “Patriarch”.1 Moreover one of his classmates, Archpriest Konstantin Izratsov, recalled, “Throughout his academic years he was secular and did not display his monastic leanings in any way. That is why his tonsure after graduation from the Academy was for many of his friends completely unexpected.”

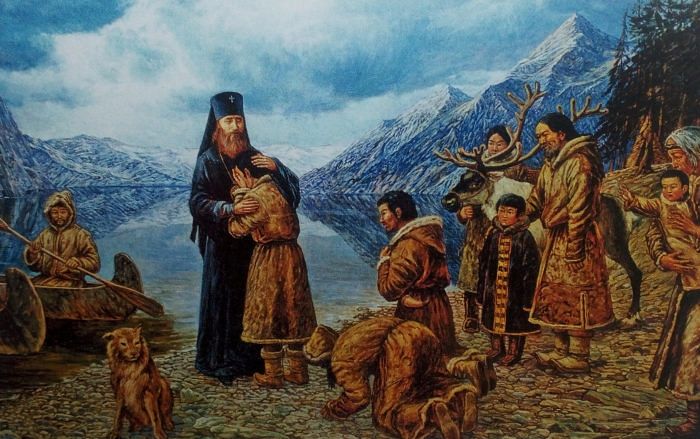

St. Tikhon travelled in places of the notorious “gold rush” described by Jack London

The future St. Tikhon in Alaska.

The future St. Tikhon in Alaska.

During his time in the United States, Bishop Tikhon made a three-month trip through Alaska. There were Orthodox parishes there, founded by Russian missionaries in the late eighteenth century. The chronicles of this journey are extraordinary. The saint stopped in settlements with unpronounceable names—the island of Unalaska, Nunapyliugmiut, Kwikpak, Nunaleanhagmiut, and Kalkagmiut.

The bishop spent time with the local population, instructed his “compatriots” to pray as Christians, and gave out crosses and icons. It is known that the future Patriarch floated down the Yukon River—along the places of the “gold rush” described by Jack London. These travels were not only uncomfortable, they were often simply perilous. St. Tikhon himself later recalled gleefully how he had to “travel through the tundra on foot, sleep for twelve hours on the ground, experience “shortages” in provisions, and "conduct a bloody but not always victorious battle with mosquitoes.”

Once the saint unwittingly pronounced a toast

In his next place of service—in the Yaroslavl diocese—St. Tikhon again demonstrated his gentleness, simplicity and openness. He travelled throughout the diocese, investigating the problems in nearly every parish, even the tiniest. Once the bishop visited a distant village where persons of high rank simply refused to go, it was so inaccessible. The locals had the impression that a “whole earthquake” had happened.

After visiting the tiny village church, the serving priest invited the bishop to his home for a festive meal. The polite Bishop Tikhon accepted. There they treated him to the local “delicacies”: pies with cloudberries, salted herring and onion, and pickled mushrooms. Having talked thoroughly with the priest, St. Tikhon was already getting ready to leave when the priest’s wife showed up. In her hands shaking with emotion she held a full shot glass on a plate. This was a gesture of hospitality from the cordial hosts, and rather than offend them the saint took a little sip; but from the drink’s unexpected strength he pronounced, “Gorko” (bitter). Hearing this as if it were a wedding toast, 2 the young matushka then and there threw her arms around her embarrassed husband and kissed him. “Yes, go on living just like that,” the bishop said affectionately, then blessed them and left.

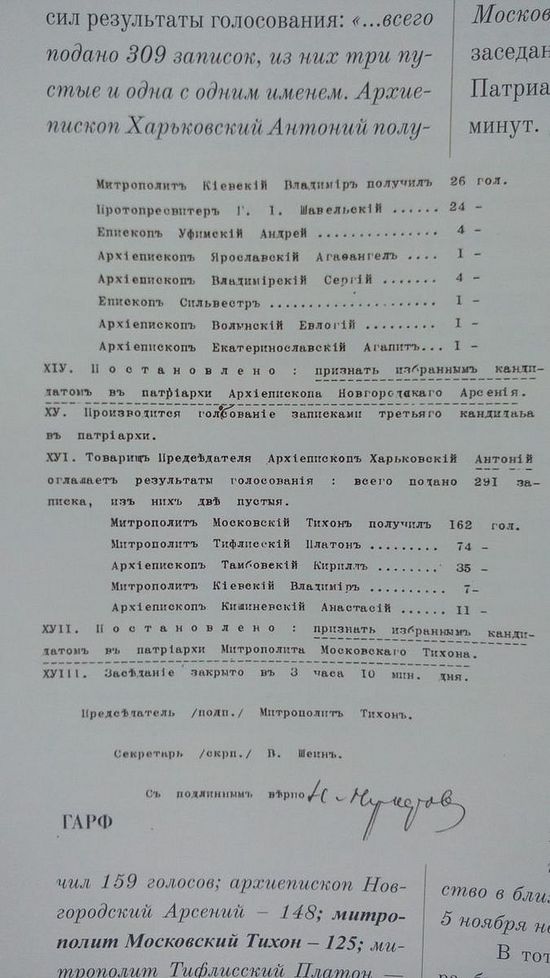

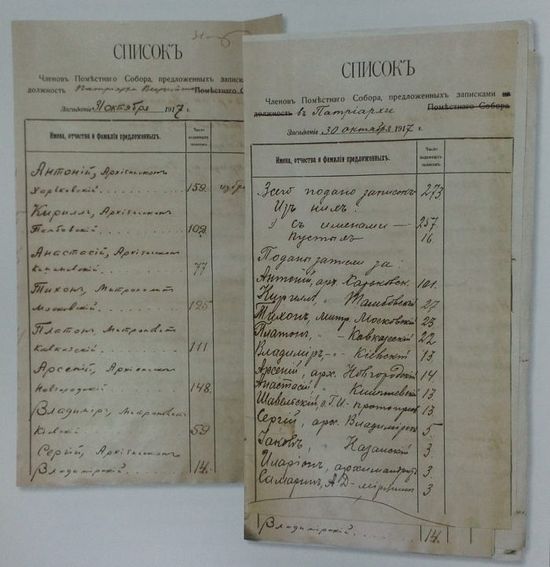

In the results of the first vote for candidates for the Patriarchal throne, St. Tikhon only took in third place

List of candidates, members of the Local Council for the election of a Patriarch. Russian state archives.

List of candidates, members of the Local Council for the election of a Patriarch. Russian state archives.

The 1917 revolution left Russian sovereignty in the past. The whole former system of church government crashed down, and the Church now had the opportunity to restore the Patriarchy it had lost for nearly 200 years.

At the All Russian Local Council it was resolved that a Patriarch be chosen. After four rounds of voting, the Council chose three candidates for the patriarchal throne. The first was Archbishop Antony (Khrapovitsky) of Kharkov with 101 votes. Next was Archbishop Arseny (Stadnitsky) of Tambov with 27, and finally Metropolitan Tikhon (Bellavin) of Moscow, with only 23 votes.

St. Tikhon was never considered the main contender for the Patriarchal throne; however at the Council it was decided that the final choice would be determined by lots—a piece of paper with the candidate’s name would be drawn. And on November 5 in the Dormition Cathedral [of the Moscow Kremlin], Elder Alexiy (Soloviev) drew the lot with the name “Tikhon, Metropolitan of Moscow”. Thus did the Russian Church obtain its eleventh Patriarch.

During the years of the Civil War (1917–23), Patriarch Tikhon did not bless the White [Army] movement.

Emperor Nicholas II and Archbishop Tikhon leave the Dormition Cathedral in the Rostov Kremlin.

Emperor Nicholas II and Archbishop Tikhon leave the Dormition Cathedral in the Rostov Kremlin.

After the revolution in Russia came the Civil War—between the so-called Reds and Whites. And although personally St. Tikhon was sympathetic to Denikin and Kolchak (he directly stated as much during his interrogation on Lubyanka), nevertheless he did not bless the Whites in the name of the Church. It is known that a party of cadets once addressed the saint, asking for his blessing. The Patriarch declined.

Prince Gregory Trubetskoy recalls another telling incident. In the summer of 1918, he was getting ready to join the ranks of the White Army, and went to the Holy Trinity Lavra metochion in Moscow to ask St. Tikhon for his secret blessing; but the “Patriarch, in the most delicate but at the same time unshakeable form said to me that he does not consider it possible to do that...”

St. Tikhon considered it unallowable for him to mix his personal stance with that of the entire Church, and called upon both sides of the fratricidal war to cease their violence.

During the terrible famine along the Volga (1921–22), thanks to Patriarch Tikhon’s connections the hungry received 50 million dollars of aid

The early 1920s. Civil war, a dry summer, and the Bolshevik politics of militant communism provoked a terrible famine throughout a huge part of the Russian territory. On the heels of the famine came outbreaks of typhus with malaria and cholera. People ate clay, bark, field animals, and sometimes even the bodies of killed people.

In summer of 1921, in the very peak of the catastrophe, Patriarch Tikhon sent a letter to the bishop of New York and the Archbishop of Canterbury, making use of the connections he had made during his service across the ocean.

The text of this letter was published in the New York Times and received an immediate response from Herbert Hoover, who was chairman of the American Relief Administration. By the summer of 1922, nearly 11 million Russian citizens received aide from the ARA every day (that meant not only food but also clothing, shoes, and medical supplies).

The Patriarch himself coordinated the organization’s activities, writing letters indicating where the aid needed to be sent for distribution to the needy. The activities of the ARA in Russia over two years totaled 50 million dollars.

Despite his aid to the starving, the soviet press called the Patriarch a “cannibal”.

Patriarch Tikhon blesses the people.

Patriarch Tikhon blesses the people.

The Church itself contributed a huge amount to the aid fund for the starving. Knowing that this could seriously strengthen the authority of the Patriarch and the whole Church, on January 2, 1922 the Bolsheviks adopted the resolution, “On the liquidation of Church property”. This campaign was organized ostensibly to aid the starving.

In February Patriarch Tikhon responded to this resolution with a call to the faithful, for the parishes to donate their “valuable church decorations and objects that are not intended for use in the divine services,” in order to overcome the catastrophe on the Volga. The saint called the confiscation of sacred objects a sacrilege in no uncertain terms, knowing full well that the government’s resolution itself was a provocation. The soviet press reacted to this call by the “cannibal patriarch” Tikhon with a squall of accusations and histrionic indignation.

St. Tikhon did not faint in spirit even while under house arrest and colossal political pressure

From May 1922, the authorities ordered that Patriarch Tikhon be isolated on the territory of Donskoy Monastery in Moscow, “for anti-Soviet activities”. His prison was located in a small two-story house next to the gate church dedicated to the Tikhvin icon of the Mother of God. The saint remained there for over a year, until June 27, 1923.

In this building Patriarch Tikhon was held under house arrest. Now it is the St. Tikhon Museum. Photo: http://www.donskoi.org.

In this building Patriarch Tikhon was held under house arrest. Now it is the St. Tikhon Museum. Photo: http://www.donskoi.org.

What were perhaps the most difficult months in His Holiness’s life had begun. Every day he was under colossal political pressure. He was periodically called down to the Lubyanka. He was bullied, provoked, and threatened, but the saint steadfastly endured his suffering, not losing his presence of mind and spirit. He even bore it all with a smile. It is known for example that over the door of his room in Donskoy Monastery hung a sign bearing the inscription: “Not accepting questions on counterrevolution.”

One day Patriarch Tikhon returned very late from yet another interrogation. Tortured by the long wait, his cell attendant asked him at the threshold, “How was it?”

“They interrogated for an awfully long time.”

“And what will happen to you?”

“They promised to chop off my head,” he said with his usual good nature, but the Patriarch answered the question wearily.

One woman who worked for the GPU (state political administration within the NKVD), Maria Veshneva, who was assigned to watch the prisoners, recalled, “The Patriarch always returns from the Lubyanka very exhausted. And when he catches his breath—he passes through all the rooms, stops in the doorway of the duty room and looks at me, and only his eyes are smiling.”

St. Tikhon had to celebrate the New Year of 1923... with the GPU agents

The same Maria Veshneva recalls one incident in His Holiness’s life while under arrest. “When the New Year came and we (another coworker sat in the duty room with Veshneva.—Ed.) could tell by the ringing of the bells that people had begun to celebrate, and then soft steps could be heard. We turned around in surprise (the Patriarch never came at night), and saw him. He was in a silk ryassa, with a large gold cross on his chest, with scrupulously combed silvery hair. He was holding a wooden tray mounded with spice cakes, marshmallows, nuts, and apples. He placed it on the table, bowed low and congratulated us with the New Year. We rose and also congratulated him, wishing him good health and luck. Then we made some tea, called the guard and had a grand New Years celebration.

There were several attempts on Patriarch Tikhon’s life

St. Tikhon was fifty-nine years old. Aware that arresting the Patriarch would bring them nothing, the Bolsheviks set him free. However, the man who had always enjoyed excellent health was now nearly blind, and had fainting spells. His every step was watched. His personal letters were opened. Searches continued. And the slander in the press did not die down. But the hardest moral trial was the successive attempts on his life.

Even before his arrest, on July 12, 1919, a woman in a crowd stabbed the saint in the side with a knife. The Patriarch was saved by his leather belt, which softened the blow.

Another attempt happened after the saint was freed. During the Liturgy, when the deacon came out of the altar with the Communion chalice, an unfamiliar man shouting, “Tikhon, we’re going to kill you!” clubbed Metropolitan Peter on the shoulder, mistaking him for His Holiness. The criminal was immediately disarmed and taken outside. St. Tikhon stood the whole time in the altar and wept bitterly.

The saint also wept on December 9, 1924, when unknown persons broke into the Patriarchal house and shot his cell attendant, secretary, and close friend Jacob Polozov. The saint was in the adjoining room at the moment of the murder. The murderers remained unidentified, but the possibility has not been excluded that they had actually come for the Patriarch. Later it was discovered that for two nights in a row, someone had sawn the grate on one of the windows in his house on the territory of Donskoy Monastery. Then St. Tikhon was taken to the hospital for his poor health while a safer living space was looked for.

Over the seven years of his service, Patriarch Tikhon served 777 Liturgies

It is known that over the seven year of his patriarchal service St. Tikhon served 777 Liturgies and around 400 evening services. That means that the saint served about every two or three days. This was with his enormous administrative workload, and under the very onerous conditions of psychological pressure from the authorities, arrests, searches, and interrogations.

What the Patriarch said before he died.

In January 1925, Patriarch Tikhon began to have heart failures. In April, he was admitted to the private clinic of the Bakunins (the building is located as Ostozhenka Street 19, and is still there today). Only this clinic’s administration risked accepting the disgraced Patriarch (a year later the clinic was closed).

The Kekushev tenant house, Ostozhenka Street 19. Architect: Lev Kekushev. Photo: NVO – own photo, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Kekushev tenant house, Ostozhenka Street 19. Architect: Lev Kekushev. Photo: NVO – own photo, CC BY-SA 3.0.

According to his cell attendant’s memoirs, on April 7, in the early evening the Patriarch began to get very anxious for some reason. He looked at his fingers—the nails were black—and he sighed deeply, saying, “Now I’ll fall asleep... deeply and for a long time. The night will be long and very dark.” St. Tikhon repeatedly asked what time it was. At 11:45 p.m. he asked again for the last time. When he heard the answer, the saint said, “Well, glory be to God,” and crossed himself broadly. At the third sign of the cross, St. Tikhon’s arm fell lifeless.

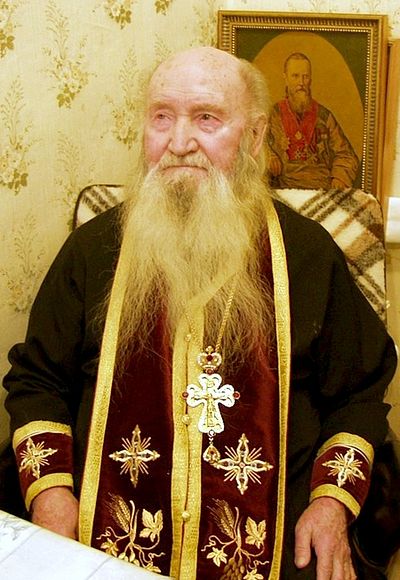

In 2006, a man reposed who had participated in Patriarch Tikhon’s burial, and then, sixty-seven years later, also in the uncovering of his relics.

Archimandrite Daniel (Sarychev)

Archimandrite Daniel (Sarychev)

This was Archimandrite Daniel (Sarychev), a monk of Donskoy Monastery. The monk recalled that he even managed to get the saint’s blessing, and then participated in his funeral service and burial. He witnessed the closing of Donskoy Monastery (in 1929), and later the renewal of monastic life in it, in 1991. Then he became a monk of the monastery. Two years later he directly participated in the uncovering of St. Tikhon’s relics.