There are dozens of cathedrals, former abbeys and parish churches across Britain which commemorate the feats of early pioneering female saints of this land—these holy, wise, brave, and independent women who enormously contributed to the formation of the English Church in its Orthodox (pre-Norman) period, in contrast with the status women had in the medieval period of history. These were saintly nuns and abbesses, queens and princesses, hermitesses and martyrs, and female missionaries. This article is dedicated to two heroic holy women who served as Abbesses of Romsey, a convent in Hampshire in southern England, which remains a holy site to this day.

***

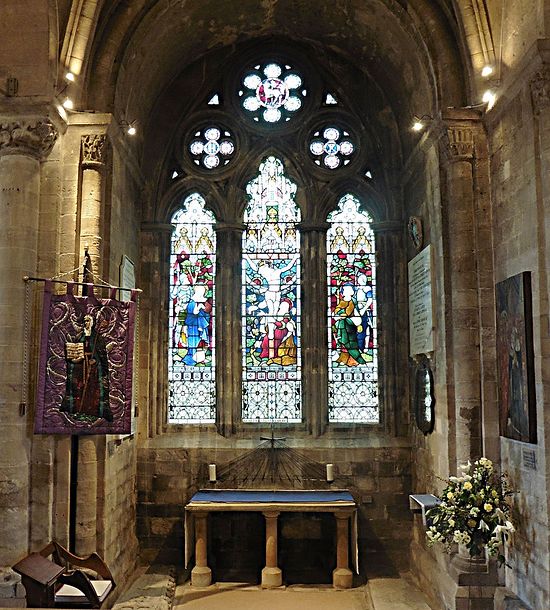

Inside Romsey Abbey, looking east (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

Inside Romsey Abbey, looking east (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The convent in Romsey in the then Kingdom of Wessex appeared in 907, when King Edward the Elder, a son of St. Alfred the Great, set up a small community of nuns there under the charge of his daughter Elfleda. Little is known about its history until its re-establishment in the early 960s by the Holy King Edgar the Peaceful. This convent, which was later dedicated to the Mother of God and St. Ethelfleda, flourished till the barbarous Reformation under Henry VIII. What remains of the celebrated convent is its large church, in which the holy memory of its first and third abbesses is still commemorated to our day. Many facts from the lives of these abbesses and the history of the convent can be found in the book by Revd. Henry George Downing Living (1861—1947), Records of Romsey Abbey: an Account of the Benedictine House of Nuns, with Notes on the Parish Church and Town. The Abbey’s history is also colorfully described in a recent book entitled, Romsey Abbey: the First 1,100 Years, by Elizabeth Hallett, to whom we are much indebted for indispensable help during the preparation of this piece.

St. Merewenna (Merwenna, Merwinna, Merewenne, Maerwynn) was most likely a member of the English nobility. In about 967, King Edgar placed her as abbess of his newly-founded Romsey Convent. The establishment enjoyed royal patronage for many years, and even Edmund, Edgar’s young son, was buried in the abbey church in 972. The community received many endowments from the royalty. As the first Abbess of Romsey, Merewenna lived a holy life, firmly developing this new community and serving as an able administrator. Thanks to her prestige and influence a large number of women and girls of high standing, including members of the royal family, chose to join this convent for years. Her signature can be found on a number of important documents of the time: among them let us mention the charter of granting lands for the rebuilding of Crowland Abbey (where she appears as the only abbess among the king, archbishops, bishops and a number of abbots) and a letter in which some sacrilegious people who were damaging the Church are denounced (among other signatories were the archbishops and other abbesses of great authority).

It is known that St. Ethelwold, bishop of Winchester, who together with the hierarchs Dunstan and Oswald contributed to the revival of the English Church in the tenth century, praised and admired Merewenna. This bishop would often consult the holy abbess, keep her informed of life in the outside world, and occasionally visit the convent seeking peace there. According to one source, the same hierarch gave several hairs of the Most Holy Theotokos to St. Merewenna’s convent from St. Dunstan.

We know more details of St. Merewenna’s life when it comes to her relationship with St. Ethelfleda, Romsey’s third abbess, who was raised and educated at the convent from her childhood.

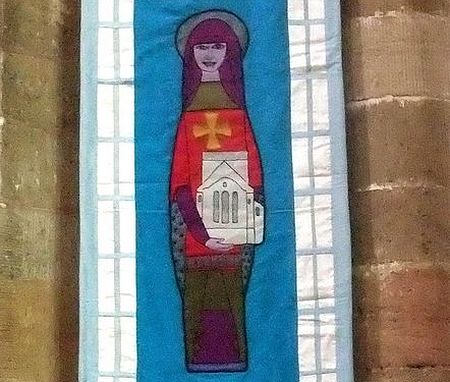

St. Ethelfleda's banner kept at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

St. Ethelfleda's banner kept at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

St. Ethelfleda (Aethelflaeda, Elfleda), whose name means “noble beauty”, was one of many children of Athelwold (Aethelwold), a pious nobleman and close friend of King Edgar, who gave to him in marriage Brichgiva—a beautiful and devout lady of near kin to his (Edgar’s) wife, Queen Elfrida. Brichgiva gave birth to St. Ethelfleda shortly before her own death. When she was pregnant she had a dream in which a ray of glorious sunlight broke out right above her head, which indicated that her baby would attain holiness. Later Athelwold remarried, but soon died, and his widow neglected her little stepdaughter Ethelfleda. Seeing this, King Edgar decided to place young Ethelfleda at Romsey Convent and entrust her to the care of Merewenna, who became a foster mother to her. It is believed that the main purpose of the nunnery’s re-foundation was that Ethelfleda would become its abbess when she was old enough. Let us quote Revd. Living, mentioned above, who relates the life and miracles of St. Ethelfleda, citing a fourteenth-century manuscript of the abbey church library which is still extant:

“King Edgar delivered Ethelfleda to the Blessed Merewenna, Abbess of Romsey, which he had constructed, to be brought up by her. After a time the Blessed Merewenna, having proved her to be active in the works of saintliness and obedience, recognized her as one who would undoubtedly profit under God’s favor in the church. She cherished her with the privilege of so great a love, that in going out and coming in, by day and by night, she desired to have her continually in attendance. And right well did Abbess Merewenna behave as a most sweet mother to Ethelfleda, and Ethelfleda as a most loving daughter to Merewenna. The one taught the way of the Lord in truth as a most modest mother, and the other, by entire obedience as a dutiful daughter, retained zealously what she had been taught. The one, as a torch of light, showed the way without error along the path of righteousness, the other, delighting in such a leader, followed without stumbling. The one on fasting days chastened her body by hunger, the other, whatever by abstinence from food she withheld from the body, she distributed to the poor in secret.”

St. Merewenna reposed in about 990, having ruled her convent for over twenty years. She was venerated as a saint soon after her death, and her feast was celebrated on February 10, the date of her repose. Later, after St. Ethelfleda’s repose, the relics of two holy abbesses were enshrined close to each other in two linked chapels, and throughout the Middle Ages they also had a joint feast day—October 29.The remains of the convent ruled by St. Merewenna have been found under the tower and part of the nave of the present Romsey Abbey church. With time, however, the veneration of St. Ethelfleda, who worked many miracles, somewhat eclipsed that of St. Merewenna, though today interest in both holy women is steadily reviving.

But let us return to St. Ethelfleda. All the medieval authors testify to the deep mutual affection of St. Merewenna and her young disciple St. Ethelfleda. Ethelfleda was tonsured while still an adolescent by St. Ethelwold of Winchester not long before King Edgar’s death in 975. When St. Merewenna reposed in 990, Ethelfleda was still not old enough to assume this post, so the second abbess was Elvina. She ruled the convent for several years. It was during her abbacy that Romsey Abbey fell victim to a Viking raid. The Danish pirates landed at Southampton and sailed up the River Test in search of riches. This most probably occurred in 994. One night, while praying by the altar, Elvina had a vision of Danes attacking and burning their convent. Without wasting time, the abbess gathered her sisters, took the convent’s treasures and fled to Winchester (the capital of England at that time), where they took refuge at the local convent called Nunnaminster. They stayed there safely for a few years until the danger was past. It appeared that the Vikings had burned down the convent, though the church may have partly survived. In any case construction work was carried on. The nuns came back to Romsey no later than 1012—the year when Queen Emma gave lands to the convent. In all probability they had returned much earlier. St. Ethelfleda became the third abbess in about 996. The community may have been in Winchester when she was elected, but she did take active part in the rebuilding work. Sadly we know little factual information about the abbacy of this saint, though we do have a collection of accounts of her miracles, which draw an image of a very holy and virtuous woman who led a very strict monastic life. She was always generous to the poor, kind and humble, and much loved by all her nuns and Christians in the region.

Her biographers say that Ethelfleda was “abundant in virtues”, “generous in alms”, “constant in watches”, “in speech vigilant”, “in mind humble”, “of joyful countenance, and kindly mannered to everybody. And in order to hide her holiness and be able to help the destitute she pretended at table among her companions to drink when she did not drink, and to eat when she did not eat, hiding in her sleeves the food which she was going to distribute among the poor. The saint never missed prayers or services or the canonical hours at church: neither secular business nor greatest ailments of body deterred her from praying and serving God. She was so diligent in singing and reading that the Lord once deigned to show how great she was in His eyes. Once on her night for reading the lesson she went up to the lectern, but the candle that she was holding in her hand was suddenly (and providentially) extinguished. The saint slightly raised her right hand, and instantly a bright radiance shone around from her fingers and made the clearest light for those around her to read. And this supernatural light did not disappear until the entire reading was over.

The following miracle occurred when Ethelfleda was a young nun at Romsey. It happened once that her cruel teacher went into an orchard of saplings near the house where Ethelfleda with the other young girls would study. While the senior nun was cutting the switches, Ethelfleda miraculously saw through the wall of the stone house, as through a glass, the saplings in the hands of the nun cut for lashing her and her companions. The nun, returning and carrying the switches, concealed them under her clothes and had scarcely crossed the threshold of the house when her student Ethelfleda exclaimed in a loud voice, with tears prostrating before her feet: “Do not beat us with the switches: we will sing at your pleasure as long as you command. When we gladly carry out your orders, why do you chastise us?” The nun, astonished beyond measure, said, “Tell me how you know that I have brought switches.” And Ethelfleda said, “I saw you under the tree when you plucked them, and you are still holding them underneath your clothes.” Ashamed, the nun decided not to lash the girls. What was done by the teacher could not have been known by her pupil except through the Holy Spirit. The sight of this girl had pierced the thickness of a stone wall, by the power of the Almighty.

The following miracle is perhaps the most famous one. St. Ethelfleda made a custom every night of leaving the dormitory for a place where she could most conveniently and secretly immerse herself in the cold water of a running stream (part of the River Test), and stay in it for as long as time permitted, singing the Psalms together with some prayers. And she persevered despite the cold and her lightest possible attire. The same kind of spiritual labor (praying in the cold water at night) is characteristic of many Celtic and some early English saints, and St. Ethelfleda appears to be one of them. It happened once that the Queen Consort Elfrida, mentioned above, called St. Ethelfleda to herself and kept her honorably in her chamber. She unwillingly stayed there for a short time, always fearing that the deceitful pleasures of earthly vanities might distract her mind from her purpose. On her arrival, sitting on a terrace and looking around, Ethelfleda saw nearby a spring of fresh water. She went to it every night, as had been her custom at the convent, when the others were sleeping, through the door or the window, sang and prayed in the water as long as was possible. Having returned, she was found in the morning in bed like the others, apparently sleeping.

One night, when the Queen could not sleep, she saw the holy virgin go alone from the room, and she imagined her to be going out for immodest purposes at such an hour of the night. The handmaiden of Christ went out, and the Queen followed. The former, having made the sign of the Cross in the water, jumped in, while the latter, obviously seeing a sign from heaven, returning to the threshold of the room, screamed loudly in hysterics and fell to the ground, as if she were out of her mind. Those who were nearby gathered around her in wonder, and took her into their arms, but the Queen was tossing about without coming to her senses. What had happened was revealed to St. Ethelfleda, who immediately prostrated herself on the ground, praying unceasingly and shedding tears until the Queen was restored to her former health.

One of her bailiffs, to whose keeping the properties of the church were committed, who was St. Ethelfleda’s household servant, placed in her coffers for safe-keeping the whole payment which he was obliged to render in one year for custody. However, Ethelfleda, whose care was always for the poor, took it out of from the coffers little by little, and distributed all the money given her to the poor. When it was time for the bailiffs to render account of the rents received for the whole year to the steward, the servant demanded back the money which he had delivered to the abbess. But of all the money only one farthing was found. The bailiff did not know what to do and St. Ethelfleda was placed in no less difficulty. With hope and confidence, she directed her earnest prayers to God: “O Lord who created all things out of nothing and caused all things created by Thee wonderfully to obey Thy commands, multiply on us Thy mercy. God, who multiplies the things we have, and wonderfully restorest the lost, restore the money spent on the needy to the honor of Thy Name.” As soon as she had finished the prayer, the coffers, previously empty, were found full of money, and after calling the bailiff, returned all the money to him with great joy. The holy abbess ran into the church, knelt down, and thanked God for a long time.

St. Ethelfleda reposed in the first half of the eleventh century: probably in about 1016, though some give 1030 as the year. At her wish the abbess was at first buried humbly in the graveyard outside the church, but later, as the miracles increased, her relics were translated into the church. Numerous pilgrims flocked to the relics of St. Ethelfleda for healing throughout the Middle Ages, and the prayers of many were answered at once. The name of Ethelfleda of Romsey was included in a number of early English (greater and lesser) litanies; her memory was also kept at Hyde Abbey in Winchester and other places. In time an annual four-day fair in honor of St. Ethelfleda was instituted in Romsey. Unfortunately, the relics of both St. Merewenna and St. Ethelfleda were lost during the Dissolution of Monasteries under Henry VIII. At present the veneration of St. Ethelfleda is reviving among Orthodox living in the UK, and recently the first Russian Orthodox icons were painted with her depiction.

According to the surviving records, the abbey church under St. Merewenna was built of stone. It was cruciform, with the nave length similar to that of the present church, but its porticoes extended beyond the walls of the church we see today. The stone used for the walls was from the Isle of Wight, and for the roof they used Purbeck stone. The convent buildings were grouped to the south of the church around a cloister. Interestingly, the townspeople may have been granted permission to use part of this church for worship also—at least from the tenth to the early twelfth centuries. As writes Derry Brabbs in his Abbeys and Monasteries in Great Britain, “In those pre-Conquest times, Romsey achieved a reputation as a place of learning, a safe haven where Saxon nobility could send their daughters to be educated in religion and other subjects in a sympathetic environment.

“However, in common with many other ‘finishing schools’, the students were not totally cut off from outside influences, as one of their number, a daughter of Margaret, Queen of Scotland, was successfully courted by Henry I.” In fact the girls educated at Romsey Abbey were not forced to become nuns and could leave the convent anytime if they didn’t feel the calling to take the veil. One of the daughters of King Malcolm III of Scotland, Matilda (baptized as Eadith), was a student of Romsey Convent at the time when her aunt Christina was a nun there. King William II Rufus, a son of William the Conqueror, came to Romsey to woo her and even convince her to marry him. However, Christina took a dislike to William; she hastily changed the girl’s dress for a monastic habit and told her to kneel down in front of the altar. Christina had to explain to him that the princess had already given monastic vows and had been betrothed to her heavenly Bridegroom. After William II perished during a hunting trip in 1100, his younger brother, the future King Henry I, came to Romsey to propose to Matilda, and Christina gave her consent. Thus Matilda became the famous “Good Queen Maude”, known for her charitable works.

The last three arches of the present abbey building were finished by 1240—by that time the convent community boasted over 100 nuns. In 1348 the Black Death decimated the population of the country, including Romsey, so the number of the nuns shrank to nineteen. Though wealthy, this convent never fully recovered after that. Such eminent figures as Kings Henry II, Edward I, and Archbishop Thomas A Becket were visitors to Romsey Abbey. Princess Joana, King John Lackland’s daughter, was among its students, and Mary de Blois, daughter of King Stephen, served as its abbess for five years.

Romsey Abbey has been used as an Anglican parish church since the 1540s. Faithful townspeople saved it from demolition after the Dissolution by joining together and buying it for 100 pounds. They had to pull down an extra south aisle (that had been purposely built for them as an extension to the abbey church) because the whole monastic church would have been too large for them. In 1643, during the Civil War, Parliamentary troops stormed the church, damaging the seats and destroying the organ. After a long period of neglect in the nineteenth century the abbey entered its stage of renaissance, especially under the rector Edward Lyon Berthon (1813–1899) — a prominent cleric and inventor, who invented the “Berthon folding boat”.

The exterior of Romsey Abbey in honor of the Virgin Mary and St. Ethelfleda, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The exterior of Romsey Abbey in honor of the Virgin Mary and St. Ethelfleda, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

This huge ancient building dominates the small medieval market town of Romsey to this day. Most of the architecture of the abbey is Norman. Norman and Early English Gothic arches in the nave are as high as a three-storied building (its three stages are called the arcade, triforium and clerestory) and date back to the period between 1120 and 1250.The initial stage of its construction was supervised by Henry de Blois, a renowned and active bishop of Winchester, to which diocese it has always belonged. The abbey remains the largest parish church in use in Hampshire, the most intact Romanesque church in England, and is often mistakenly taken as a Cathedral by visitors who see it for the first time.

The Saxon rood in St. Anne's Chapel at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The Saxon rood in St. Anne's Chapel at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

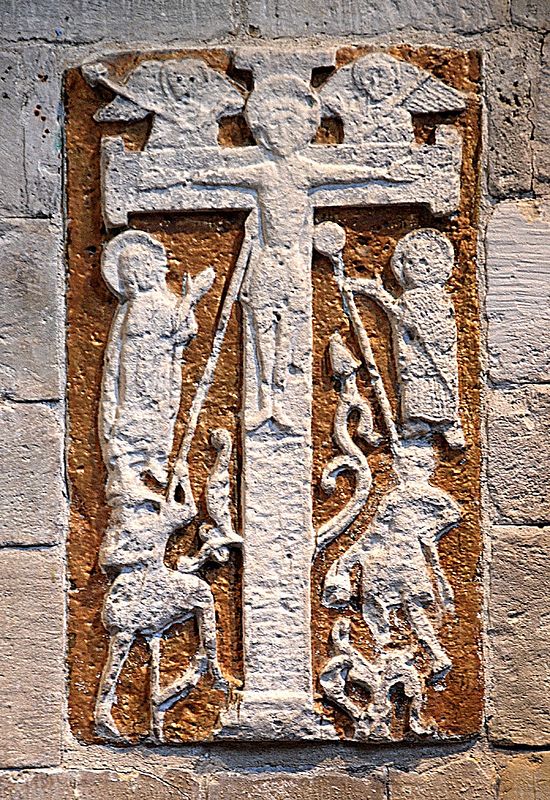

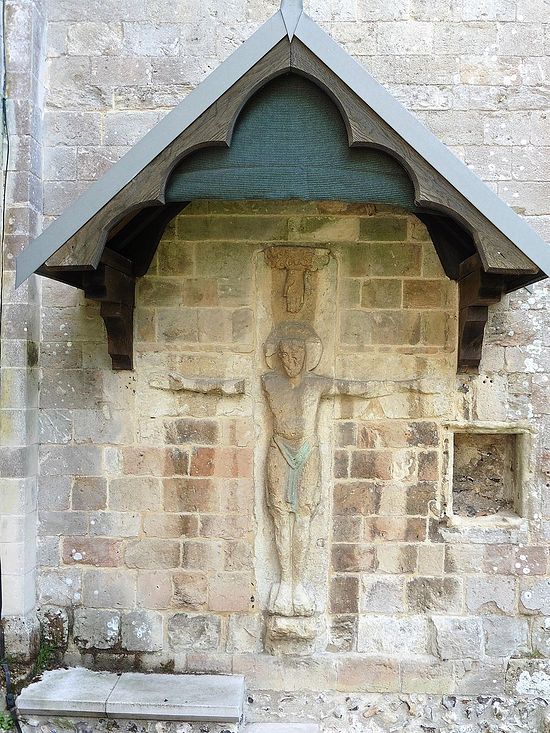

The gems of Romsey Abbey are its two stone Saxon roods (crosses). Only a handful of pre-Norman crucifixes across Britain survive, but Hampshire can be proud of preserving several of them. Both roods were moved from the Saxon church to the current abbey after the Normans had begun the construction of the abbey in 1120. The interior crucifixion carving dates back to the late 900s, which means that St. Ethelfleda must have seen it with her own eyes, while the external cross dates back to the early 1000s. The almost life-sized early eleventh-century rood can be found on the exterior western wall of the south transept. In fact both crucifixes would originally have stood inside the Saxon church, but after the completion of the stone Norman church they were installed inside the new monastic church despite the fact that the Normans rarely appreciated Anglo-Saxon art and sculpture.

The hand of God, the exterior rood at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The hand of God, the exterior rood at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The rood must have included the figures of the Mother of God and St. John the Evangelist on either side of the Crucified Christ, but these were lost. However, the Hand of God the Father appearing from the cloud above Christ’s head indicating that the Savior is His only beloved Son, still survives. Typical of the Anglo-Saxon period is the way Jesus is depicted reigning from the cross triumphant, with His face very welcoming and serene. This is not the Catholic Christ of agony and Crucifixion—this is the Orthodox Christ the King, the triumphant Savior, extending His victory and sacrifice at the same time.

The exterior rood at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The exterior rood at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

There is a manuscript of the same period (the 990s) in the British Museum, which contains a homily of Abbot Aelfric of Eynsham, with a drawing of another life-size crucifix on it virtually identical to this one! As writes Nick Mahew Smith in Britain’s Holiest Places: “How the exterior rood… has survived in such adverse conditions—weather and the Reformation chief among them—is unclear. Perhaps it stops everyone in their tracks. People no doubt queued up to kiss this effigy’s feet… Some crucifixes, such as this one, gain more power from being battered. Perhaps it underlines the function of the cross, a lightning rod for human failings.” Some reckon this rood to be the oldest of this kind in all Britain.

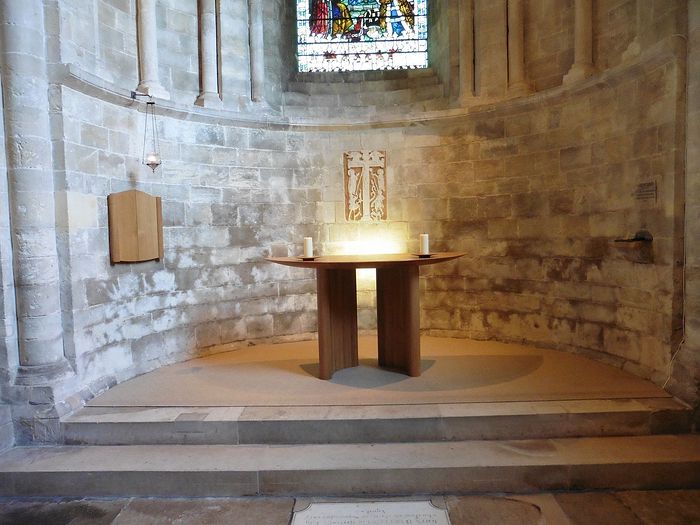

The altar and Saxon rood in St. Anne's Chapel of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The altar and Saxon rood in St. Anne's Chapel of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The internal rood carving is located in St. Anne’s Chapel—behind the altar at the southernmost corner of the church—and represents Christ being pierced by a spear and offered vinegar on a sponge. Though this panel is considerably smaller, it is better preserved. It reminds one of Orthodox crucifixes. There are St. Longinus the Centurion and another soldier who offered the Savior vinegar. The Mother of God and the Apostle John are above them, and angels are seen hovering by the arms of the cross. Originally the scene was painted, and now the background is covered with gold paint. Some suggest it dates back to the 960s and was a gift of King Edgar.

There is a wealth of monuments commemorating St. Ethelfleda at Romsey Abbey, though sadly there are no obvious ones dedicated to St. Merewenna. Among them let us mention:

a) A banner, used by Romsey Abbey in processions but housed in St. Ethelfleda’s Chapel in between times;

b) The abbey has her image as one of the saints on a curtain. The embroidery was done mostly by students aged sixteen and seventeen in 1961.

St. Ethelfleda depicted on the red staff of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

St. Ethelfleda depicted on the red staff of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

c) She appears on the two staffs (staves) carried by the abbey churchwardens on special occasions, such as when the Bishop visits. The staves are their staff of office, just as the abbesses carried a staff called a crozier.

St. Ethelfleda depicted on the blue staff of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

St. Ethelfleda depicted on the blue staff of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

d) The abbey has a special “Ethelflaeda Festival” each year around her saint’s day, October 23 in the calendar of the Church of England. This lasts for four or five days and they have concerts, a lecture, activities for the children, often a display of art work of some sort—but all intended to show the importance of women in the Church, since Ethelfleda was a nun. For the Festival they have a special banner which is on display for those days—this is a copy of the image on the curtain and was worked by a member of the congregation.

St. Ethelfleda depicted on the festival banner of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

St. Ethelfleda depicted on the festival banner of Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

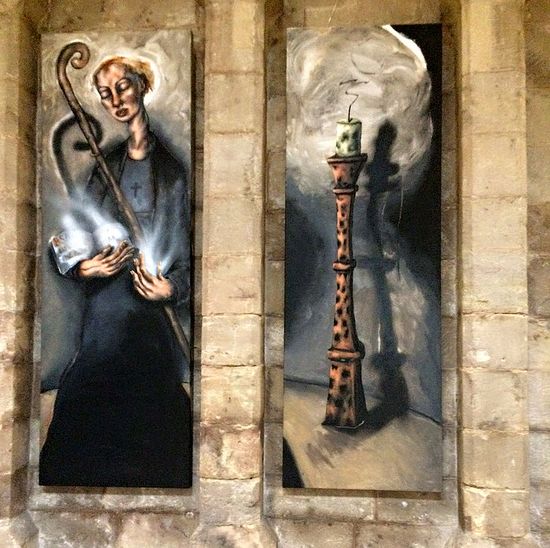

e) The abbey has recently acquired a painting of St. Ethelfleda showing one of her miracles, when the candle blew out and the tips of the fingers of her right hand lit up so that she could see to read to her nuns. It is depicted in a diptych created by Chris Gollon and is kept in the south aisle.

The painting on a diptych showing one of St. Ethelfleda's miracles by Chris Gollon (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The painting on a diptych showing one of St. Ethelfleda's miracles by Chris Gollon (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

f) And, lastly, the abbey has a side-chapel in her memory. Initially it was probably a passageway leading to the saint’s original pre-Reformation chapel. Though the surviving abbess’s elaborate coffin lid there is not Ethelfleda’s (as was formerly believed by a number of historians)--it dates to about 200 to 300 years later. There are a couple of other “candidates” within the abbey, but in the recent years it was proved that these graves belonged to later abbesses or assistant abbesses and certainly not to St. Ethelfleda or St. Merewenna. For example, there is a (presumably) Saxon grave stone at the back of the nave featuring a hand clutching a staff, as if some committed abbess were unable to cease her duties even after her death.

St. Ethelfleda's Chapel at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

St. Ethelfleda's Chapel at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

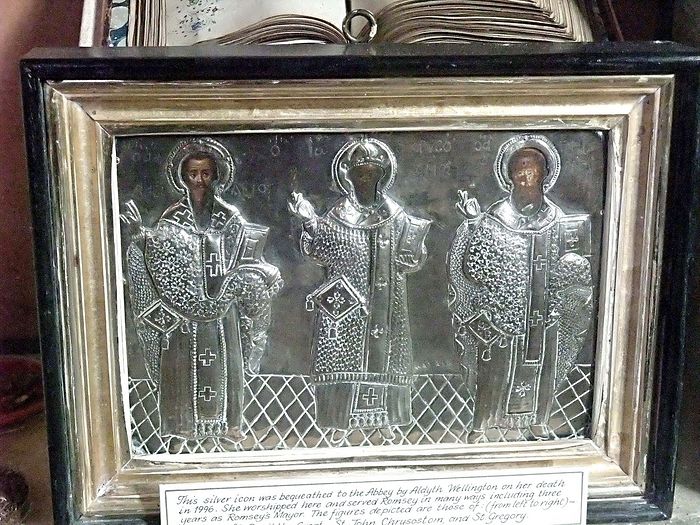

Romsey Abbey (along with other historic churches in Britain) has managed to acquire a number of icons over the years. The most striking example is the silver Orthodox icon of the Three Holy Hierarchs—Sts. Basil the Great, John Chrysostom, and Gregory the Theologian; it was a gift in the 1960s.

The silver icon of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The silver icon of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The braid of hair discovered at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

The braid of hair discovered at Romsey Abbey, Hants (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

An interesting relic from an early burial is kept at a display case at the west end of Romsey Abbey. It is a beautiful complete head of Saxon hair with a long braid (over eighteen inches long), originally resting on a block of wood which formed a pillow. It was discovered in 1839 in a lead coffin when a grave was being dug at the eastern bay of the south aisle. When it was found, the hair was in perfect form, and looked as if the skull had recently been removed from it. No bones were found in the perfectly-preserved coffin except for one finger which turned to dust with the first contact with air. Initially it was conjectured that it was a braid of hair of one of the late Saxon princesses who had lived at Romsey Abbey, but there has been no evidence to support this version so far. In fact until 1853 Church of England permitted the burial of bodies of some departed people inside church buildings, so Romsey Abbey (as well as a host of other churches) does have remains of a large number of important persons under its floor. Though the hair was examined by radio carbon dating a couple of years ago, we don’t actually know yet whether it is the hair of a man or a woman, but hopefully further research will be able to identify--they are still working on it. The lovely story is that the young man who has carried out the tests came from Romsey and as a child he was taken with his school to see the abbey. He was fascinated by the hair and decided then and there to be an archaeologist when he grew up and to find out about it--which is exactly what he has done. It is a really good reason for showing visitors including children around churches.

Madonna and Child by Travers inside Romsey Abbey, installed 1935 (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

Madonna and Child by Travers inside Romsey Abbey, installed 1935 (provided by Mrs Elizabeth Hallett, Romsey Abbey)

Elsewhere at the abbey visitors can admire St. Nicholas Chapel which houses the grave of Louis, Earl Mountbatten of Burma (an uncle of HH Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh[1]), who lived locally, and a modern statue of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker by Peter Eugene Ball; twelfth-century wall-paintings with the scenes of the Life of St. Nicholas at St. Mary’s Chapel (restored in the 1970s); St. George’s Chapel that contains a contemporary sculpture of Christ the King in glory by P. E. Ball, and a statue of George the Victorious vanquishing the dragon, with the floor tiles which are 700 years old; the late fifteenth-century “Romsey Cope”—a ceremonial robe of green Italian velvet with silver gild thread and silver star patterns; a relief of the Madonna and the Christ Child by Martin Travers above the High Altar; a display of the Saxon finds discovered around the church at the west end; the quiet St. Laurence’s Chapel with a unique large Italian painted board which was used as a reredos behind the altar and one can light candles in this chapel. This abbey has a rich collection of stained glass windows (there are both Victorian and Gothic ones among them), exquisite Norman carved capitals and corbels. Romsey Abbey is noted for its rich musical tradition. Unlike most English cathedrals and abbeys, one of Romsey Abbey’s main choirs has always been made up of girls, thus this important tradition of the former convent is maintained. The choir’s recordings are known all over Europe, and it tours other European countries as well.

Romsey (the name probably meaning “Rumbald’s island”), a Hampshire town seven miles from Southampton, ten miles from Winchester and eighty miles south-west of London, standing on the outskirts of the famous New Forest, was described (in a very sentimental manner) by the author and traveler Henry Vollam Morton (1892–1979) in his collection of vignettes entitled, In Search of England, written in the mid-1920s.

A collect prayer for St. Ethelfleda from Romsey Abbey:

Almighty God, by whose grace the Abbess Ethelflaeda, kindled with the fire of Thy love, became a burning and a shining light in the Church: inflame us with the same spirit of discipline and love, that we may ever walk before Thee as children of light: through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen[2].

Holy Mothers Merewenna and Ethelfleda, pray to God for us!