The Church of St. Nektarios of Aegina

The Church of St. Nektarios of Aegina

In the very heart of Aegina

Bright sun, fresh and salty sea wind, the aroma of invigorating Greek coffee, the fragrance of white, violet, and pink bougainvilleas—the wind here is rough and perceptibly saturated with smells and sounds; tirelessly and sweetly cooing turtledoves. All around spread small mountains with rocky flat tops, nearly devoid of vegetation. On the slopes of the mountains, among the shrubs, olive trees, cypresses, and low spreading mountain pines, there’s a spread of small homes with terraces and brown slopes of tiled roofs. We’re on the small Greek island of Aegina, about twenty miles from the Athens port of Piraeus.

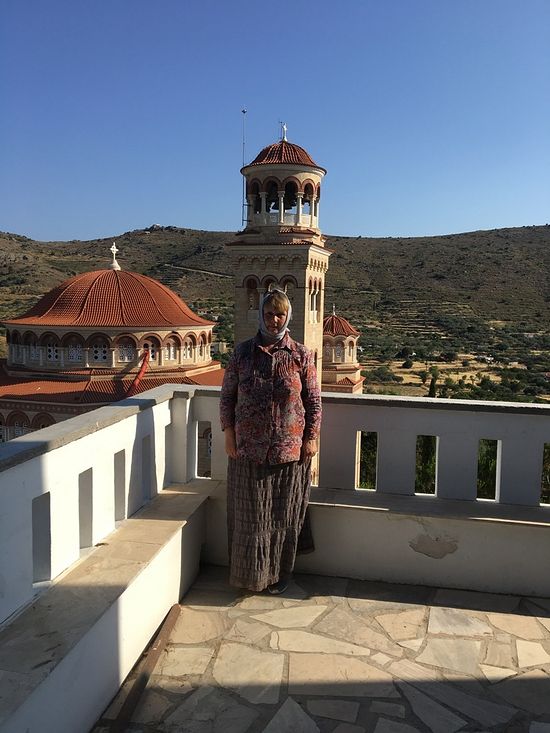

With Sister Nektaria under the same mountain pine where St. Nektarios usually spoke with the sisters of the monastery

With Sister Nektaria under the same mountain pine where St. Nektarios usually spoke with the sisters of the monastery

Around Aegina are azure sea expanses, and on the island itself—seven monasteries and a huge number of small churches and chapels. At one time, the Turks forbade the building of large Orthodox churches here and required that the church be built in one day, otherwise they would destroy the building. In cafes, stores, and small shops, in hotels and private homes on Aegina, St. Nektarios of Aegina (1845-1920) looks out at the guests from old photographs and icons. Holy Trinity Monastery, which he founded and is now often referred to by the name of its holy founder, is located in the very heart of the island.

“The cross and crucifixion are part of my life”

Both in childhood and adulthood, St. Nektarios knew what poverty was. All his life he was persecuted by slander, calumny, and persecution. Having left his parent’s poor home as a boy, he worked a lot, studied independently, was sometimes beaten by his master, and suffered undeserved accusations and reproaches. Thanks to his brilliant mind, his extraordinary thirst for knowledge, his great diligence, and his fervent prayers, he received an excellent education and became no less than the Metropolitan of the ancient Metropolis of Pentapolis.

But even here he was slandered before the elderly Patriarch as allegedly planning to take his throne. He was deprived of any opportunity to defend and justify himself and was ordered to leave the city and go wherever he might. Upon returning to Athens, he couldn’t get even the humblest of places and, as in his childhood and youth, had no money for food.

In the first years of the creation of Holy Trinity Monastery on the site of ancient monastery ruins on the island of Aegina, St. Nektarios himself carried water, hauled rocks for construction, cultivated a garden, and fixed the nun’s shoes. But slander did not leave him alone here either; the Elder bore the heavy affliction of denigration, and he was threatened with an unjust judgment. After an investigation, the charges were dropped, but what suffering he had to endure! By the end of his life, there were thirty-eight nuns laboring in the monastery he founded, and Vladyka himself, according to the sisters, was all aglow during the Divine services. Many saw him floating in the air during prayer.

When Vladyka was very ill and suffering in the last year of his life, he consoled himself with walks through the mountains to the neighboring monastery, where he would pray for a long time at the “Chryssaleondisa” (“Golden Queen”) Icon. He loved to contemplate the Lord’s sufferings on the Cross, because his own life was like a cross. He would say: “The Cross and crucifixion are part of my life.”

When the holy hierarch became very ill, the sisters took him to the hospital in Athens, and the doctors couldn’t believe that this poorly-dressed old man was a metropolitan. He was placed in the poor ward, where he spent two months in severe sufferings, praising the Lord and praying without ceasing. The miracles by his prayers began immediately after his blessed repose, and now there are too many to count.

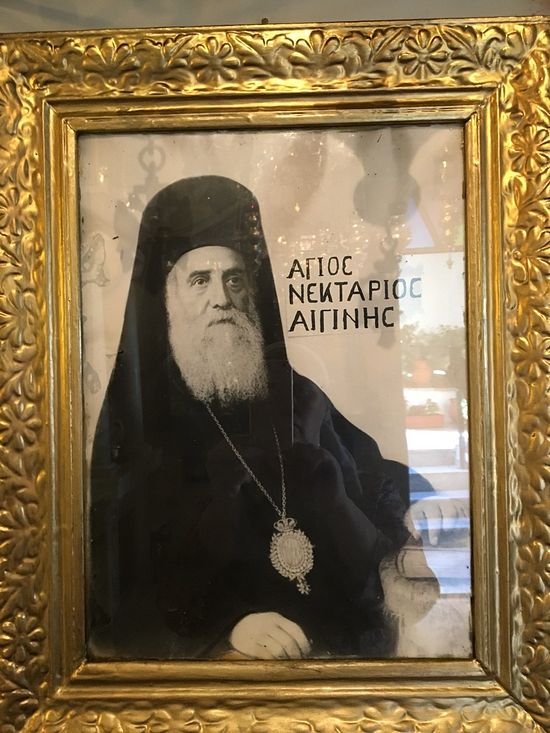

St. Nektarios of Aegina, Metropolitan of Pentapolis

St. Nektarios of Aegina, Metropolitan of Pentapolis

Meeting in the monastery

There is a special silence in the inner courtyard of the Monastery of St. Nektarios, interrupted only by the gentle cooing of turtledoves. There are fragrant flowering plants and a fresh breeze pleasantly blowing from the mountains surrounding the monastery.

I was greeted with love. The abbess of the monastery, Gerondissa Theodosia, blessed me with lunch and fruit. Gerondissa is eighty-three and she is a spiritually-experienced eldress. While in the world, she worked in a bank, but spent all her free time in a sisterhood. In Greece, a sisterhood is like a monastery in the world. The sisters have an intense spiritual life, great missionary work, and social activities, and they do a lot of work with priests.

Gerondissa blessed two sisters to have a conversation with me for Pravoslavie.ru—the Greek nun Christonymphy and the Russian Nun Philothea. The sisters told me about the monastery today, about the its joys and difficulties, and the miraculous help of St. Nektarios.

Sisters Christonymphy and Philothea

Sisters Christonymphy and Philothea

St. Nektarios still cares for us

Sisters Christonymphy and Philothea talk about St. Nektarios as one living: “Our Vladyka loved the monastery very much, cared for his spiritual children, always asked the sisters what he could bring them, and brought them everything himself. He’s gone to the other world now, but he still cares for us. We ask him, and he helps us. If one of the sisters needs something, St. Nektarios helps her solve the problem. We really feel his support and his presence here. He follows everything from start to finish. If one of the sisters needs a doctor, he finds her precisely the doctor she needs.”

I experienced the truthfulness of the sisters’ story, many times. The first time, the strap on my bag that I usually wore over my shoulder unexpectedly broke in the monastery. It was extremely uncomfortable to just carry it in my hands.

When I went into St. Nektarios’ cell, I quietly lowered my bag to the floor and began to read the Akathist to the saint. The sister on duty didn’t ask me anything, but just picked up my bag and took it into the hall. I was embarrassed: Maybe I shouldn’t have just put it on the floor in the cell…

Peering cautiously into the hall, I saw the sister skillfully sewing a rather thick and firm strap on my bag, and I was going to look for a large shoe needle for it, as I was sure a simple needle wouldn’t work with the leather strap. I didn’t manage to finish reading the Akathist before the strap was sewn, so securely and firmly that I could only grasp it with amazement and thank the attentive and friendly Greek woman. When I told Sister Philothea about it, she wasn’t surprised at all: “Vladyka Nektarios is so thoughtful! He cares even about the little things! He made shoes for himself and the sisters, so how could he let you go on your way with a torn bag?!”

Sister Philothea speaking about St. Nektarios

Sister Philothea speaking about St. Nektarios

How St. Nektarios introduced me to St. Minas

The second time I experienced the care of St. Nektarios was when I returned from the monastery to the village of Agia Marina, where I had booked a room in a small family hotel. Buses come by the monastery at fairly large intervals, and I was already ready to look for a ride, but right at the gates of the monastery I noticed a car with two Greek women. They kindly agreed to take me, but only a third of a mile, to the highway, because they had to go in the opposite direction, to the city of Aegina (the monastery is located halfway between Agia Marina and Aegina).

As we were going down this glowing hot road, we got to know each other. It turned out that one of my fellow travelers lives in Arizona, near the Monastery of St. Anthony the Great, founded by Geronda Ephraim of Philotheou. It also turns out that she read my articles about the monastery. After such discoveries, we felt almost like family, and my companions abruptly changed their plans.

They didn’t just go the opposite of the way they needed to go, they didn’t just take me to my hotel, but took me to the Monastery of the Great Martyr Minas, well known to them, where they introduced me to the sisters of the monastery and showed me all the churches and sacred objects. We venerated the icon of St. Minas, tried some delicious loukoumi and cookies, refreshed ourselves with ice water, thanked the nuns, and only then went to Agia Marina.

The next day, in response to my story about my absolutely wonderful and unexpected trip to the Monastery of St. Minas, which I wasn’t trying to get to, Sister Philothea said: “It’s all Vladyka Nektarios! You see, he introduced you to his co-struggler and spiritual patron—St. Minas!

And Sister Philothea told me about the spiritual connection of the two saints.

Entrance to the Monastery of St. Minas

Entrance to the Monastery of St. Minas

How St. Minas visited St. Nektarios

Once, while St. Nektarios was alive, one of the nuns of the monastery was in a hurry to ask his advice, and, peering into the cell of her spiritual father, she saw how he was speaking with a very presentable middle-aged officer. The sister excused herself and went into the hall to wait for Vladyka to be free. She waited for the end of the conversation a long time, but couldn’t wait the whole time: The interlocutor of her spiritual father hadn’t come out through the only door leading from the house to the street.

When St. Nektarios realized the sister was witness to the miracle, he told her that his interlocutor was St. Minas and forbade her to reveal the story to anyone until his death.

St. Minas is celebrated almost at the same time as St. Nektarios—November 11 and November 9. The holy Great Martyr Minas lived in the third century and served as a soldier in the Roman army. He is greatly revered in Greece together with other holy warriors—George the Victory-Bearer, Demetrius of Thessaloniki, and Theodore Stratelates.

Testimonies about St. Nektarios

The grandparents of today’s inhabitants of the villages around the monastery knew the saint well and asked for his prayerful help and often spoke with him. Now their grandchildren pass on these stories to the sisters. The older sisters also tell the younger sisters what they heard from the nuns who have already departed for the other world.

When St. Nektarios would serve the Liturgy, everyone present experienced such grace, such bliss, that no one wanted the service to end. Such a gift he had.

St. Nektarios greatly revered the Most Holy Theotokos and spoke to her formally, but entreated her with such faith as if she were there with him. He would say: “O Lady Most Holy Theotokos, help me, please, and entreat your Son. But we need it urgently!”

Vladyka wrote several thousand verses dedicated to the Most Holy Theotokos, some of which were used for the very famous Orthodox song “Agni Parthene.”

The Lord glorified St. Nektarios as a wonderworker, but he was also a remarkable spiritual writer and an outstanding theologian. He has thirty volumes of theological works. Scholars are amazed at how one man with so many responsibilities could write so much!

The holy hierarch prayed a great deal, standing, and his legs were sore and very swollen.

His words are widely known in the monastery: “You know that no one can come to me unless I call him.” Everyone who comes to the saint for help receives it.

In the Monastery of St. Nektarios

In the Monastery of St. Nektarios

In the Monastery of St. Nektarios

In the Monastery of St. Nektarios

“My relics are my stole”

When St. Nektarios departed to the Lord, because of the slander they even had to get permission to bury him as a priest, and his spiritual children, themselves priests, received permission to bury Vladyka in priestly vestments. When they put a stole on him, St. Nektarios raised his head and helped put this stole on him.

Thirty-three years after his blessed repose, the holy hierarch looked as if he had just died. From 1920 to 1953, his tomb was opened several times, he was revested, and he remained completely incorrupt. Even the flowers placed in his grace turned out to be alive every time.

Then he appeared to one of the nuns and said: “Put my old vestments on me; I will go around the world with my relics.”

And only then, after thirty-three years, did his body turn into relics. The words of St. Nektarios are well-known: “My relics are my stole.”

Vladyka was numbered among the saints in 1961, his memory being celebrated on November 9. In his cell, in a prominent place, there hangs a gramota with the confessions of the Alexandrian Church that the accusations against St. Nektarios were false. Among the apologies are the following words: “We did this out of human infirmity, being tempted by the evil one.” The gramota is signed by Patriarch Peter VII of Alexandria and All Africa, whose memorial visit to Aegina took pace in 1998.

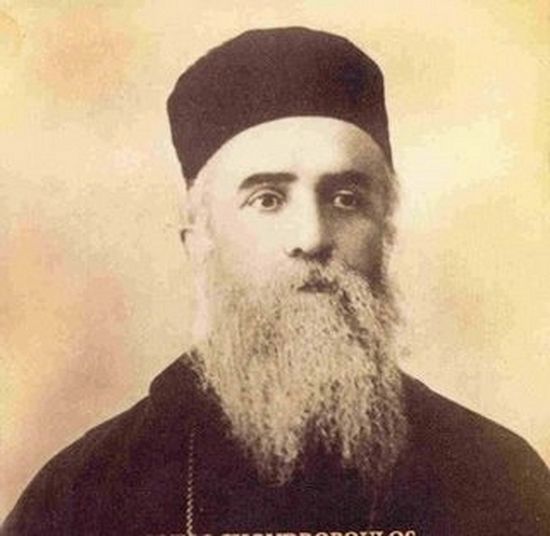

How St. Nektarios looked for several years after his burial

How St. Nektarios looked for several years after his burial

The gramota of apology of the Patriarch of Alexandria

The gramota of apology of the Patriarch of Alexandria

A wonderworking icon

In St. Nektarios’ cell, on the chest of drawers, is a large icon of the Most Holy Theotokos. This icon was painted on Mt. Athos. St. Nektarios brought it with him from Athens and really loved to pray before it. The sisters of the monastery venerate it as wonderworking.

In the 1980s, a council was assembled in Greece, where they wanted to ban all icons of a non-Byzantine style (in short, for non-professionals, not planar, but voluminous icons, more conveying human appearance than symbolism).

Then this argument was put forth at the council: “What about the icon of the Most Holy Theotokos in the cell of St. Nektarios of Aegina? It is non-Byzantine, but it is miraculous!”

After that, the participants in the council started mentioning examples of other wonderworking icons in non-Byzantine styles, and that was enough to not forbid them.

Wonderworking icon of the Most Holy Theotokos before which St. Nektarios prayed

Wonderworking icon of the Most Holy Theotokos before which St. Nektarios prayed

We try to preserve the very spirit of St. Nektarios

Sister Philothea also spoke about the contemporary life of the monastery and the precepts of St. Nektarios:

The entire life of our monastery is built according to the precepts of Vladyka Nektarios. Perhaps some external conditions of our monastery life have changed, but we try to preserve the very spirit of St. Nektarios, of his sacrificial service to people.

The monastery used to have this rule: After the Liturgy, the sisters wouldn’t talk amongst themselves all morning; they prayed and remained in silence. Now we have a large number of pilgrims and there is no such rule, but we still try to speak only about work and not fall into idle chatter.

Under St. Nektarios the monastery was very poor, lacking the most basic necessities. For example, they had no frying pans, and the sisters couldn’t fry anything or prepare those dishes that we cook now. These days we can cook everything, but that’s not the most important thing. The elderly residents of the local villages who have been visiting the monastery since their childhood for many decades, testify that everything remains simple here, without any pomp, without any special ceremony—everything is like under the saint.

We try to preserve the love that was in our monastery under its founder, and we try to suffer the infirm and the sick and to serve people.

From the external typikon, it is preserved that the Chapel of the Holy Trinity remains as small as under St. Nektarios, and only women are still allowed to enter. Men pray in the neighboring chapel, where rest the precious head and relics of the saint.

The climate here on Aegina is warm. In winter, the temperature is 32F, rarely dropping to around 20, but it still becomes cold in such weather due to the high humidity in our cells, which have no central heating. It’s easier for us now: We can use heaters, but under St. Nektarios, the sisters moved burning coals from one cell to another to warm themselves. They also sewed riassas from blankets to keep warm outside and in church.

The living room in St. Nektarios’ residence

The living room in St. Nektarios’ residence

The chapel with the tomb of St. Nektarios under the mountain pine

The chapel with the tomb of St. Nektarios under the mountain pine

Our routine and statutes

We usually rest six hours in the day: from 9:00 PM to 3:00 AM. At 3:00 AM, the sisters get up and read the cell rule. Usually that’s 500 prayers, and 3,000 for schemanuns. Every sister has her own additional, individual rule—a certain number of prostrations depending on strength and age. There are sisters who labor in vigils, pray fervently, and, with a blessing, sleep less than the monastery statues allow—that is, less than six hours a day.

At 4:30 we go to church and get it ready for the service, lighting the lampadas. At 5:30 we have the Midnight Office. The monastery is still closed; only the sisters pray at the Midnight Office. The doors open for pilgrims at 6:00 AM and don’t close until sunset—all day long. Liturgy is served every day. Priests come to us—Archpriest Nicholas and Fr. Andreas. The sisters confess, as usual, to the priests, and they reveal their thoughts to the abbess—either written or orally, depending on desire and circumstances.

The sisters usually commune four times a week, on Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays, and there’s a number of sisters who commune on fasting days and fast additionally. It’s not an example to be emulated for all monasteries or laypeople—it’s the statutes of our monastery.

After the service we have some coffee and eat some olives and bread and a piece of loukoumi. Then we work at our obediences. At 1:00 PM we have lunch. We have sixteen sisters—one Russian, two Romanians, and the rest are Greeks. The obediences are typical for a monastery: in the garden, at trapeza, on the kliros, around the relics. We have a small garden, but we don’t keep any animals. We don’t have any chickens or cows or goats. We give much time and energy to receiving pilgrims.

Our sisters consider the best obediences to be handiwork in their cells, making prayer ropes, or sewing, so they can say the Jesus Prayer undistracted by anything. Even being alone at an obedience in the garden can’t compare with obedience in the cell, because in the garden or in the mountains, in nature, the mind is distracted from prayer.

Under St. Nektarios, after lunch the sisters rested for an hour, but now it doesn’t always work and it depends on the obedience: Those who have urgent obediences can rest a little later.

In the winter, the evening service begins at 4:00, then we close the monastery. In the summer it’s open all day and the evening service is served around 6:00 PM. After the evening service there is dinner—some of the sisters go and some don’t—according to desire. Then we have the evening rule, and then the sisters disperse to their cells, they pray, they read the Holy Fathers, and they reflect on the spiritual life. It’s not blessed to keep food in the cells, except, perhaps a little bread and water.

There are few sisters in the monastery, but much work; but I want to note that all of our obediences go on without tension, peacefully, by the prayers of St. Nektarios. In the world, such work, in the garden, at the trapeza, receiving pilgrims, would require considerable effort, but here, by the prayers of our dear Vladyka, it all seems easy, like you’ve fallen into a fairytale.

The monastery’s inner courtyard, view from the terrace

The monastery’s inner courtyard, view from the terrace

Invisible ministry

In the summer we get a lot of pilgrims, and we have to meet and take care of them all. Throughout the entire day, our two icon shops, the chapel with the tomb of St. Nektarios, both sections of our church, and St. Nektarios’ residence, where he lived for the last twelve years of his life, from 1908 to 1920, are open. The sisters meet with pilgrims everywhere, answer questions, show them where to go, where to get Holy Water, and they distribute free holy oil and bottles of water.

It’s not a very prominent ministry, but it requires a lot of effort and time when throughout the day you have to answer the same question 200 times, give help, bring water, make coffee, show the way, to the entrance to St. Nektarios’ residence, to the trapeza, to the holy spring. Another time you go to your obedience, for example, to do the laundry, and then an entire bus full of pilgrims arrives. You drop your obedience and go to meet them—we have to manifest the sacrifice that St. Nektarios commanded us to keep.

In the winter we live in more seclusion.

How can a speechless creation praise God?

Olga, we are now sitting on the terrace under the same mountain pine where St. Nektarios held talked with the sisters, interpreted the Psalter, and answered questions. Sometimes they were caught in conversation by the roosters singing in the morning. Once the sisters asked their spiritual father the meaning of the words of the Psalmist, King, and Prophet David: Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord. How can a speechless creation praise God?

Instead of an answer, St. Nektarios prayed, and the nuns found themselves in a transfigured world, where they heard how every tree, every flower, and every little blade of grass sings the glory of the Lord.

Under this very tree St. Nektarios spoke with the sisters

Under this very tree St. Nektarios spoke with the sisters

St. Nektarios is very helpful to the sick

Many Romanians come here—they love St. Nektarios dearly. They say: “He’s our saint!” But the greatest number of pilgrims come to us from Serbia. They had a huge increase in cancer following the bombardment with uranium warheads. And St. Nektarios greatly helps these sick people.

Besides the usual pilgrimage buses, entire buses full of cancer patients come. It’s terrible to look at them: they are thin, pale, emaciated people with stage 3 or 4 diseases. They themselves talk about it and how it’s metastasized. And we’re no longer surprised when these same pilgrims come again a few months later and tell us about their significant improvement or even to give thanks for their healing.

Many patients, after their trip to St. Nektarios, have another analysis done or undergo examination again before continuing their course of treatment or having surgery, and the results of the analyses or examinations testify to a complete healing!

Silver and metal plates with gratitude to St. Nektarios

Silver and metal plates with gratitude to St. Nektarios

Doctors couldn’t believe the pictures

One priest, Fr. Dalibor from Leskovac, Serbia, told us how the parents of a sick boy who had symptoms of brain damage came to him. They did a CT scan and found a huge tumor. They scheduled the boy for a complicated operation with a skull trepanation.

The priest blessed all the boy’s relatives to reconcile if they had had any fights, and to read the Akathist to St. Nektarios of Aegina for the healing of the child—and the boy was completely healed. The doctors were amazed. They couldn’t believe the pictures, but with a CT scan, the brain is scanned with accuracy down to the millimeter.

(During this story, I surmised that Sister Philothea was a doctor. And I was right: She worked as a therapist for seven years in Russia after finishing a medical institute.)

“Go to the church and venerate St. Nektarios!”

Another Serbian priest told us a story as well. When he was a young man, not even thinking about becoming a priest, working as an economist, his mother told him she had been diagnosed with leukemia. He was very worried for his beloved mama, and one night he saw a church in a dream.

The Lord said to him: “Go to this church and venerate St. Nektarios!”

The young man recognized the church, in Belgrade. As soon as he woke up, he heard on the radio: “A wonderworking icon of St. Nektarios of Aegina has been brought to Belgrade…”

This loving son immediately went to the church and prayed at the icon of St. Nektarios, entreating his prayerful help. After his prayer, his mother had to do an analysis again—and there was no trace of leukemia. From that very moment, his mother was completely healthy and often comes to our monastery.

But that’s not the end of the story. This young man’s spiritual father went to see the bishop of the Niš Diocese and told him about the miracle. Vladyka listened and said the young man needs to become a priest.

When the spiritual father told his spiritual son about Vladyka’s blessing, the young man had another dream, and in this dream St. Nektarios himself ordained him to the diaconate in a church with which he was not familiar.

When the young man’s ordination to the diaconate took place in reality, he realized it was in the same church that he saw in the dream. Now the former economist is a priest.

Holy Hierarch Father Nektarios, pray to God for us!