I first met Mother Nadezhda in the mid-1990s. It was clear from first sight that she was a nun. Short, lean, in a dark coat and headscarf, she was wearily walking along the street with a heavy bag in her hand. “Can I help you?” I asked. “Yes, please help me, honey…” she said simply. This is how we met.

I first met Mother Nadezhda in the mid-1990s. It was clear from first sight that she was a nun. Short, lean, in a dark coat and headscarf, she was wearily walking along the street with a heavy bag in her hand. “Can I help you?” I asked. “Yes, please help me, honey…” she said simply. This is how we met.

She would go to the Liturgy every day, and would always go to Vespers on the feasts. Over twenty years have passed since, but in my mind’s eye I can still see her standing by the icon of the Theotokos of “the Three Hands” at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Stavropol [a city and the administrative center of the Stavropol territory in North Caucasus in the south of Russia.—Trans.], where she would always pray, turning over the pages of the cathedral’s countless lists with the names of the living and departed to be prayed for…

Her old acquaintances would have been unlikely to recognize in this bent over old woman the happy, prosperous and beautiful lady whom she had formerly been. Who could have suspected that her path had contained events that would have sufficed for several lifetimes, though she had never expected or desired anything supernatural.

Nun Nadezhda (secular name: Vera Petrovna Borodinova; 1917—2006) was born in village Mikhailovskoye in what is now the Stavropol territory. She was nicknamed “the nun” in her childhood. As a girl of five she would often gather other children and say: “Let us pray.” The grown-ups were puzzled: why was it so quiet in the room? Having opened the door slightly, they would see the children praying on their knees in front of the icon shelf, with Verochka [a diminutive form of the name Vera.—Trans.] at their head.

“At school I was a top student and a class monitor, but I was a permanent church-goer too. When our teacher rebuked me, I replied, ‘This doesn’t hinder my studies! I will go to church as I have done!’” Mother Nadezhda recalled.

At the age of nineteen Vera married. Her neighbors laughed softly: “Well, that nun has gotten a husband through prayer!” But she had never thought of marriage. All happened as if automatically. A young and handsome pilot proposed to her. It was a nice surprise to her parents and they were happy. So Vera obeyed her parents…

Thus, Vera overnight turned from a poor, modest girl who wore patched dresses into a lady of good social position. The nun recalled that her husband had led her into a shop in a big city and bought its whole selection, dressing her “to the point of elegance.”

Their family life, though it didn’t last long, was peaceful and happy. Anthony, Vera Petrovna’s husband, was kind and sensitive, and they never argued throughout their marriage. He taught their sons, Anatoly and Vladimir, to respect their mother and be responsible to people. Vera Petrovna took active part in the lives of the soldiers. Together with other officers’ wives she would launder, sew and decorate their barracks as well as she could. After the Second World War her spouse was sent to Japan, and the family lived in that faraway country for some time. One day Vera suggested they move to a more comfortable apartment where they could use the properties of its previous owners. “You don’t say so, Vera! These are someone else’s tears!” he replied.

Of course, he knew about his wife’s deep faith. The household always tried to keep fasts; Vera Petrovna attended church services frequently; and Anthony never stopped her by a word of judgment or ban—on the contrary, he showed thorough understanding.

Anthony perished when Vera was only thirty-four. The whole division mourned its commander as everybody loved him dearly. And Vera thought that her life had ended and she had nothing else to expect from it. “I wept over my husband day and night,” the nun related. But God’s plans for her life were different.

She proceeded with her story:

“After the funeral my mother, my sister and I travelled to many monasteries and convents to order services for his repose there. I remember us visiting Kiev, its Lavra, and especially Elder Kuksha (Velichko), who is now ranked among the saints. Later I visited him several times in Odessa, and he blessed me to become a nun and gave me his prayer ropes.”

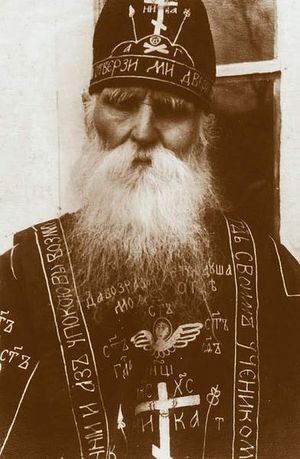

At that time Schema-Monk Damian (Korneychuk; 1863—1954), a great recluse who took a vow of silence, was struggling at the Kiev Caves Lavra. Though he didn’t hear confessions, sometimes he allowed pilgrims to call on him and receive his blessing. For Vera Petrovna, the meeting with that ascetic became a turning point in her life that divided it into two parts: “before” and “after”. She would often remember Fr. Damian and recount what had happened there with great joy.

At that time Schema-Monk Damian (Korneychuk; 1863—1954), a great recluse who took a vow of silence, was struggling at the Kiev Caves Lavra. Though he didn’t hear confessions, sometimes he allowed pilgrims to call on him and receive his blessing. For Vera Petrovna, the meeting with that ascetic became a turning point in her life that divided it into two parts: “before” and “after”. She would often remember Fr. Damian and recount what had happened there with great joy.

“I remember us entering his cell. He blessed everybody and then treated us to the monastery’s tasty kvass [a traditional Russian soft drink made of bread.—Trans.]. The only thing I was thinking about was how I should live out my widowhood and how to ask him about this. Then everybody began to leave. I left too. But I suddenly remembered that I had left my bag behind in his cell. All of a sudden the door opened, and his cell-attendant said, ‘Let the owner of the bag come in.’ I entered. The elder was standing in front of the icons and praying. I fell on my knees, weeping and repeating all the time: ‘Father, I am the worst sinner!’ I was shedding floods of tears. I don’t know how long I was there, but as soon as I had gone outside, the world turned around in my eyes with a strong sense of purification as though I were a teenager. I told those close to me: ‘If I were to experience a miracle of my husband’s return, I would live with him as with a brother.’”

Indeed the future nun’s life was transformed thenceforth. Even her appearance changed: she tied up her hair and began to wear a dark plain polka dot dress instead of expensive outfits. Her neighbors, acquaintances and relatives kept saying in one voice, “The colonel’s widow has gone mad.”

Vera Petrovna lived close to the Church of the Exaltation of the Cross, where Metropolitan Anthony (Romanovsky; 1886—1962) of Stavropol and Baku then served. They kept in touch, and she often performed tasks he gave her. After services she and several friends would go to care for the sick, weak and minister to the elderly. The metropolitan’s precept was the following: “Don’t tell me how many prayers you have read but how many sick you have visited.” One day a woman she didn’t know came up to her in the street and hugged her: “Thank you for attending to my mother right till her death!” Metropolitan Anthony himself set a good example of compassion for and mercy to people. According to her reminiscences, not only did he support the needy—he would always also send parcels to the monasteries and convents that lived in dire poverty at that time.

Vera Petrovna lived close to the Church of the Exaltation of the Cross, where Metropolitan Anthony (Romanovsky; 1886—1962) of Stavropol and Baku then served. They kept in touch, and she often performed tasks he gave her. After services she and several friends would go to care for the sick, weak and minister to the elderly. The metropolitan’s precept was the following: “Don’t tell me how many prayers you have read but how many sick you have visited.” One day a woman she didn’t know came up to her in the street and hugged her: “Thank you for attending to my mother right till her death!” Metropolitan Anthony himself set a good example of compassion for and mercy to people. According to her reminiscences, not only did he support the needy—he would always also send parcels to the monasteries and convents that lived in dire poverty at that time.

Both of Vera Petrovna’s sons became doctors. The elder one became a famous surgeon, and the younger, Vladimir, died young. He had asthma, a genetic disease, from which Vera Petrovna suffered for a long time too. But in 1988, on the day of the canonization of St. John of Kronstadt in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), where she had been brought half-dead, during the solemn service she was healed from this disease completely.

She had known many strugglers for piety of the twentieth century personally: Archimandrite Seraphim (Tyapochkin), Schema-Hieromonk Sampson (Sivers), Schema-Hieromonk Stephen (Ignatenko), and others… For many years she helped Fr. Peter Sukhonosov1, who was martyred by militants in 1999; she had known him since his years at seminary and they were tied by close spiritual bonds.

Vera Petrovna lived in “yards”. These “yards” are a peculiarity of southern Russian cities. Up to ten families normally live in the same residential building, with another one attached to it, with sheds and some other structures adjoining it and tiny flower-beds and vegetable patches close by. Opened doors and windows with shouts, music, aromas of Caucasian and Cossack cuisine and many other things, typical for the region, coming from them. It was in one of such “yards”, that our future nun lived in a little house that was sinking into the ground. She occupied a tiny kitchen-lobby, along with two small rooms with low ceilings. All the walls were covered with icons and paintings with Biblical and Gospel scenes.

We were neighbors, and I would often come to see her. However heavy at heart I felt, I always had peace of mind after talking to her. Small and swift, Mother Nadezhda had time for everything; and whenever she was praised, she replied with tears in her eyes: “I am not a monastic! Monastics are those who bear the Lord in their hearts!”

Every single day of hers began with the Liturgy even when she was ill, even if it was snowing or raining outside. How many times she fell onto the ice-covered ground, hurting or bruising herself badly, but then got up and walked to church… On one occasion she hurt her head very badly but nevertheless came to the service. Afterwards it turned out that she had concussion, but she didn’t lie down for a single day after the incident. Having stood through long hierarchical services, she would stay at church waiting for Vespers, and only after that did she go back home. “What have you eaten today, mother?” I would ask her. “I ate, I ate,” she brushed my questions aside. “What exactly?” I would insist. “I drank tea after Vespers.” And she also travelled to Moscow to petition for the opening of a church in Raguli [a village in the Stavropol territory.—Trans.]. She appealed to the Head of the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church, established at the Council of the People’s Ministers in the USSR. And she succeeded: the church was opened!

People would often seek her advice right in church: where to light a candle, how to confess and take Communion—and she would always answer in detail with love. And whenever she saw improper appearance or conduct in church in someone, she would say gently: “Honey, that’s not the way we behave in church...” People couldn’t help but respond to her childlike open smile and warm look.

One of the most remarkable episodes of her life is the story of her tonsure. Many elders had foretold that she would become a nun. But Vera Petrovna didn’t want to hear about this because she considered herself unworthy. At the age of seventy-two she fell so sick that they invited her elder son. Seeing his mother’s serious condition, he asked an acquaintance who was standing beside in a low voice: “How are we going to bury mom?” Among those who had come to see Vera Petrovna was her intimate friend who suddenly suggested: “Vera, you should take the angelic habit; otherwise you will die without fulfilling the elders’ blessing. But if you do, all your sins will be forgiven.” At first she refused, but then she put up with it and said: “Lord, direct my steps! May Thy will be done in all things!” On the same day, the blessing of Metropolitan Gideon of Stavropol and Vladikavkaz was received, a nun’s habit found, and in the evening the tonsure took place, during which she was given the name Nadezhda in monasticism. Throughout the ceremony she lay, barely able to breathe. But she didn’t die… To everyone’s surprise, Mother Nadezhda began to recover, got up from bed, and finally came to church. All who had visited her were astonished! And, as before, she resumed praying, ministering to the sick, consoling, and visiting monasteries and convents. “This is how things work sometimes. She was so ill! But now all who tended her during her illness have long gone, and she is still alive, glory to God!” Archpriest Peter Savenko she was close with used to say.

At the age of eighty-two Mother Nadezhda visited Holy Land for the first time in her life. She climbed up Mount Sinai unaided. And those who first chuckled at the seemingly infirm little old woman reached the summit later than her, according to her own testimony. Mother Nadezhda couldn’t have imagined that several years later she would go to Jerusalem again, then would end up at a hospital, and then would no longer be able to move unaided. “I am glad I was vouchsafed to suffer where our Lord suffered!” she used to say to those who sympathized with her. Nun Nadezhda spent the final years of her life at the Holy Annunciation Convent in Kirzhach [a town in the Vladimir region.—Trans.]. It was there that she fell asleep in the Lord on October 22, 2006 at the age of eighty-nine.