Vasily Konoplev hesitated. Always so confident and reasonable, a veritable pillar for the faithful, he was now in doubt. It is good that these doubts will be resolved very soon. Very soon—tomorrow morning. If it is not resolved as expected, it means everything he had lived up to now was wrong, and he’ll have to cross everything out and start life all over again. Only the strong can admit their mistakes without prevaricating, honestly, without self-justification. Will he be able to? Will he find this strength?

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

In the village of Ilinsky, in a remote corner of the vast Perm Governorate, a verst1 from White Mountain, they didn’t talk about anything earthly—they discussed things heavenly. A warm sunbeam looked in through the open window of the spacious hut, walked along the clean floorboards covered with homespun rugs, running from the warm faces of the ancient icons in the beautiful corner2 to the old books—the Psalter, the Horologion, and the Menaion.

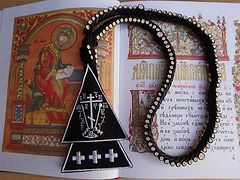

There were a lot of people sitting on large, solid benches in the hut: staid men of various ages with full beards listened attentively to the reader. In their hands—leather lestovkas, each of them usually praying a cell rule of ten lestovkas a day, and some more, according to their zeal; and with prostrations and bows. They prayed on their lestovkas for their incorrigible souls—three prostrations for each.

At last, the reading of the instructive narrative from the manuscript collection of bygone years finished, and the men began to amicably discuss what they had heard, without interrupting, taking turns to instruct one another in the spiritual life. The prerogative to instruct belonged, however, to the learned head of the priestless Old Believers Vasily Konoplev.

Vasily was an exceptional man. At ten years of age, he learned to read and write and prayed with the bezpopovtsy,3 with the elders and the regular people. When he came of age, he loved to read the Divine Scriptures. He gave all his free time to the reading of books, buying them or asking to borrow them from others to read.

And the zeal of podvig gradually began to flare up within him. At night, he often arose in prayer before the icons of the Lord Almighty and the Most Pure Theotokos and prayed fervently, with tears. He would ask the Lord: “Lord, open my eyes. Grant me to understand the path of salvation! Tell me the way which I should go; teach me to do Thy will!” He spent a long time this way. Therefore, he didn’t get married—so there would be no obstacles to his examination of the true path.

In this hot, drought-threatening summer of 1893, Vasily Konoplev had just turned thirty-five. There was not a single gray hair in the dark strands of his hair or in his neat beard. The regular features of his face, the large, expressive, dark eyes, his attentive and intelligent look attracted attention. When Vasily began to speak, his speech was so intelligent and thoughtful that it became clear to everyone that the Lord Himself had given him the gift of persuasion and the gift of leadership.

That is why, despite his youth, the Old Believers of the Osinsky District, whose numerous sketes and cells were spread out near White Mountain, saw him as their head and mentor. If they recognized priests here, Konoplev would definitely have become a priest. But they didn’t recognize them.

The Old Believers didn’t disperse after the reading. Everyone awaited a communal meal—generous and sufficient. Old Believer households were well-off—as they say, fat. If you labor with your soul and don’t drink wine, the Lord will send everything. They were famous for beekeeping. Vasily himself had a good-sized apiary and notable honey…

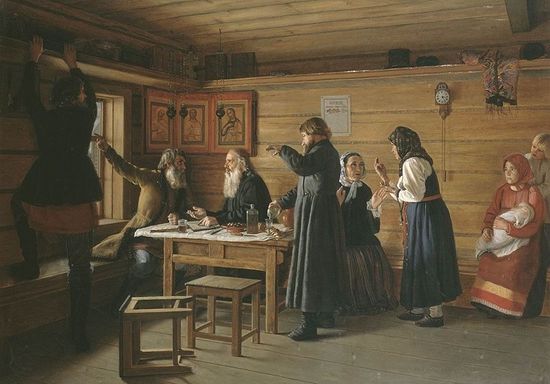

A dispute about the faith. Artist: D. E. Zhukov, 1867

A dispute about the faith. Artist: D. E. Zhukov, 1867

They sat at the table. They each took out their “communal” cup and towel. After the meal, everyone would wrap their cup in their towel and take them with them. Vasily liked the strict, long-established rhythm; he liked the rite and the order. His soul loved it. There should be order in everything—it is good and pleasing to the Lord. After all, He too has ordered the ranks of angels and archangels, and they all sing in harmony, not discordantly…

Once Vasily went on pilgrimage to Cheremshanksy Monastery in the Saratov Governorate—a schismatic lavra, and he liked it so much that his old dream of becoming a monk again arose in his soul. At the All-Night Vigil there were many regular monks, with gray-haired schemamonks in front; hundreds of lit candles and burning lampadas in front of the rich iconostasis, the readers reading unhurriedly, clearly, and reverently, everyone crossing themselves and bowing at the same time—order and splendor… But he didn’t decide to stay yet. He returned home.

In general, in the Osinsky District, safely far from the parish churches and pastoral care of the Perm Diocese, many schismatic leaders of various sects had settled: Pomorsky, Chasovenny, Belovodsky, Avstrisky—each doing his own thing. And each sect considered its teachings the most correct, the truest.

Vasily was a fervent schismatic and his speeches even led the Orthodox into doubt. He well knew that there was much in the Orthodox Church that disagreed with the books that existed before Patriarch Nikon. He would call the Orthodox heretics who brazenly perverted the holy teaching of Christ and the apostles, but he couldn’t prove it. He was seeking the truth. That’s how he was since his childhood.

He went to Moscow, going all around: the Khludov Library, the Synodal Library, St. Nicholas Monastery… He went to the St. Sergius Lavra. He spoke with the abbot of the St. Nicholas Edinovertsi, that is, Orthodox, Monastery, Fr. Paul. He was a former Old Believer. He had converted to Orthodoxy. Such a wise elder! He received him with great love. Forgetting his old age, he spoke with Vasily for a long time. And through his words about the fullness of the gifts of the Orthodox Church, which has succession from the holy apostles, Vasily was swept up into a storm of doubts about his rightness. He lost sleep. You could say he was in despair. How to know the truth?!

And in the St. Sergius Lavra, he saw a book written by the hand of St. Cyril of White Lake. It turned out that what they, the Old Believers, accused the Orthodox Church of was incorrect. And the ancient books confirm it… The Lord brought Vasily to see with his own eyes words about which they, the Old Believers, argued and called innovations and heresy: the name of Jesus, the Nicene Creed without the adjective “True,” alleluia three times followed by “glory to Thee, O God,” and so on.4

And when he went home, he found out that the Orthodox served molebens on White Mountain for the sending of timely rain. And whenever they would finish—it would rain. What could this mean? God doesn’t hear sinners…

Vasily decided for himself: Like Doubting Thomas, he would believe only when he saw everything clearly for himself, with his own eyes, or when they undoubtedly proved which Church has the fullness of the gifts of grace. He didn’t tell the brethren about his doubts yet—he should understand everything himself first.

While he was thinking and remembering, the common meal ended. They stood up decorously and prayed. Vasily said authoritatively: “Tomorrow we’re going to White Mountain. His Grace Peter and the clergy are coming. They’re going to consecrate the place and lay their church. Thus, we will test the prayer of an Orthodox hierarch.”

View from White Mountain (Perm Region)

View from White Mountain (Perm Region)

Stephen, a gray-haired, respectable elder, objected: “There’s nothing to test here. They always serve their moleben before the rain—of course, it rains. And now there’s a drought, and no rain is expected. They won’t be able to deceive the people!”

His son, Theodore, also gray already, assented: “It won’t work this time! A multitude of spiders are weaving webs in the forest. The cuckoo coos for a long time. And also—listen!”

They listened. They looked at Theodore perplexed. He explained timidly: “Do you really not hear? You can hear the frogs at Irena singing from here… That means, it won’t rain!”

Stephen stopped his son: “Just hold on with your spiders and frogs!”

The fathers discreetly grinned into their beards. Stephen added knowingly: “Look out the window!”

They looked out the window.

“What a clear sunset! Nice weather… And no frogs!”

They smiled in anticipation of the defeat and shame of the heretics. Vasily asked: “And what if, by the prayers of His Grace Peter at the moleben, God gives rain for the crops?”

Their smiles widened.

“What’s with you, Vasily Efimovich? It doesn’t happen that God listens to apostates!”

And with that they parted.

Vasily slept poorly that night. He got up many times. He prayed. The moment of truth was approaching.

Having woken up early in the morning, he laid a “beginning”—he prayed. He went out in his yard. He looked around. He could understand the weather better than anyone else by his worker bees. The bees headed out to their honey flow early in the morning—a good day. They won’t return soon—they flew far out into the field. Yes, by all indications, it won’t rain today!

And then Vasily, firmly convinced that it could not rain naturally, made a vow in prayer: “Lord, show me a miracle. Resolve my doubts and confusion! If the Russian Church wasn’t deprived of the gifts of grace for its change in rites, if the grace of the Holy Spirit acts through these pastors, then during their moleben, send abundant rain upon the earth, O Lord! If this happens, I will convert to the Russian Orthodox Church!”

![Belogorsky [White Mountain] Monastery](http://www.pravoslavie.ru/sas/image/102115/211598.p.jpg?mtime=1440427186) Belogorsky [White Mountain] Monastery

Belogorsky [White Mountain] Monastery

The fathers gathered on time. Silently, with a steady pace and with prayer, they moved up the mountain. The morning silence was disrupted only by the singing of the birds. Theodore couldn’t resist breaking the general silence:

“You were wrong yesterday, father, to not believe about the spiders and frogs … They are God’s creatures. I looked around in the morning: Swallows flying high in the sky, grasshoppers loudly chirping! And there was a full moon… The sky was clear at night, starry—not a cloud! There won’t be any rain!”

The scowling Stephen only grunted sternly—his son recoiled, he grabbed his lestovka and continued praying silently. Although he himself was almost fifty, he humbled himself before his father, honoring him. That’s how it’s always been with them.

Covered with green forests, White Mountain towered over the surrounding distances like a mighty giant. Huge mast firs and spruces were growing at the foot of the mountain. Lindens and maples occasionally met with the tender greenery. There was almost no road, and the path went up, passing swamps, clear streams, and a number of springs. The glades flared with red peonies, which were locally called “Mary’s Root.” Snakes didn’t like it, and therefore there wasn’t a single viper on White Mountain, thank God.

Sometimes the mountain was covered in clouds, and sometimes the clouds floated below its summit. But today the sky was cloudless.

The higher they went up the mountain, the more beautiful the view. The panorama of the vast horizon was striking with its greatness, its immeasurable air space. The dawn lit up such a distance—it was breathtaking: blue mountains, yellow fields, emerald valleys with an endless palette of shades of green. Gradually, the crests of distant mountains appeared from the height, which, bathed in rays of sunlight, became invisible to the ordinary eye in the daytime.

From the top of the mountain opened up a view in all directions, and the soul was seized by ineffable delight—he wanted to pray, to weep, and to sing praises to God: How wondrous are Thy works, O Lord; in wisdom hast Thou made them all!

On the large clear meadow, a mass of pilgrims gathered with the clergy from the surrounding villages. They were carrying icons. There was a multitude of clergy: Seventy people— priests, deacons, and chanters—came with Vladyka Peter.

Vasily felt complete confusion in his soul. What did he want? That there would be no rain and the apostates would be put to shame? Or that the Lord would work a miracle in response to their prayer? His heart was pounding, he lost his breath.

“Blessed is our God!”

The moleben began. The cloudless sky and bright sun left no hope for a successful outcome to their prayer.

“Hearken unto us, O God our Savior, Thou hope of all the ends of the earth and of them that be far off at sea, Who setteth fast the mountains by Thy strength, Who art girded round about with power, Who troublest the hollow of the sea, as for the roar of its waves, who shall withstand them?”

Neither wind nor cloud. The leaves didn’t sway. Vasily lowered his head.

“In peace, let us pray to the Lord!”

“That He mercifully send upon the earth, and upon His people, seasonable weather and timely rains, that their crops may flourish, let us pray to the Lord.”

“That He not slay His people and the livestock in His wrath, but command the clouds to let rain fall from on high and the earth to put forth its fruits, let us pray to the Lord.”

A slight movement of air touched Vasily’s face. He raised his head: The leaves on the trees were fluttering in the wind.

“O Lord Who dost determine the disposition of the weather by Thy command, grant Thou a mighty rain and seasonable weather to the earth, that it may bring forth abundant fruit for Thy people; and satisfy every living thing with Thy benevolence, through the prayers of the Theotokos and of all Thy saints.”

There was a subtle change in the air. The pilgrims raised their heads: Huge clouds raced across the darkening sky.

“O protection of Christians who cannot be put to shame, mediation before the Creator unfailing: disdain not the cries of supplication of sinners, but be thou quick, O good one, to help us who with faith cry unto thee: Haste thou to prayer and speed thou to make supplication, O Theotokos, ever interceding for those who honor thee.”

Lightning flashed. Thunder rumbled in the distance. Vasily knelt. A shiver ran down his body. Other pilgrims knelt behind him.

“Grant rain to the thirsting earth, O Savior!”

Vasily felt a large drop of water fall on his forehead.

“Peace be to all. The reading from the Gospel according to Matthew.”

Large, sparse raindrops fell upon the thirsty ground.

By the end of the moleben, there was a torrential downpour. Vasily wept, not ashamed of his tears: No one could distinguish them from the raindrops.

Archimandrite Varlaam Konoplev), builder and first abbot of Belogorsky Monastery

Archimandrite Varlaam Konoplev), builder and first abbot of Belogorsky Monastery

From eyewitness accounts:

After the torrential rain that changed the entire course of the summer and prevented the threatened drought, the leader of the Old Believers, Vasily Konoplev, who lived a verst from White Mountain, brought bread and honeycombs from home and publicly presented them as a gift to the Orthodox hierarch—His Grace Bishop Peter (Losev) of Perm and Solikamsk—in front of the Old Believers who were present there. Vladyka accepted the gift and told Vasily welcomingly: “Such a wise man won’t remain an Old Believer for long, but will soon come out of the darkness into the light and be a son of the Orthodox Church with us.”

From the journal of the Monk-Martyr Archimandrite Varlaam (Vasily Efimovich Konoplev), the abbot of Belogorsky Monastery:

“My joining the Orthodox Church took place on October 17, 1893, in the cathedral before Liturgy, celebrated by His Grace himself through the Sacrament of Chrismation… On November 6, Vladyka Peter clothed me in the riassophore and I settled on White Mountain. Gradually, everyone desiring the monastic life began to come to me, and twelve people had gathered by February 1, 1894, when I was tonsured into monasticism with the name Varlaam in Vladyka’s home church. The next day, Bishop Peter ordained me as a hierodeacon. On February 22, the altar in the little Church of St. Nicholas on White Mountain was consecrated. Vladyka consecrated it himself, and after the consecration of the altar, he ordained me as a hieromonk during the Liturgy.”

From the notes of a monk pilgrim a few years later:

“The services in the monastery churches were distinguished by solemnity and deep tenderness. The schemamonks with gentle, childlike faces had their own forms in the church; the young monks stood in the choirs, and some down below. After the evening rule in the church, the candles were extinguished, and the entire monastic army, about 500 people, barely rustling their mantias, moved towards the shrine with the fragments of relics. Then came the powerful chanting of the prayer, “It is Truly Meet,” in Athonite chant. I wanted to weep at the sound of the prayerful blessing of the Mother of God. Some bright feelings made their way into my soul in a broad wave, and I thought: ‘How satan probably trembles at these moments and hates the singing monks.’”

Historical reference:

In August 1918, the monastery was captured by the Bolsheviks. They destroyed and desecrated the altar table in the main cathedral altar, and a bathroom was set up in Archimandrite Varlaam’s cell. Many monks were killed after brutal torments. On August 12, the Red Army arrested the abbot of the monastery Archimandrite Varlaam, and on the way to the town of Osa, they shot him and threw his body into the Kama River.

Belogorsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, founded by Fr. Varlaam, Perm Region. Photo: Peter Zakharov

Belogorsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, founded by Fr. Varlaam, Perm Region. Photo: Peter Zakharov