Part 1. “I Should Kill You—You Know Communism Better Than Me!”

Part 2. “Comrade Major, This is a Monk, Not a Monarch!”

We continue the recollections of Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavlević), a friend, companion, and co-struggler of the Serbian Patriarch Pavle. Fr. Jovan published his recollections in the book Memories, printed at Rača Monastery in 2018. We offer today several episodes from this book concerning the persecution of the Serbian Church and people by the state and by Albanians.

Attempts by the authorities to destroy the brotherhood of the monastery

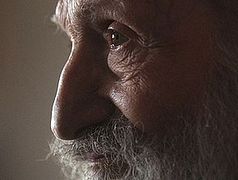

His Holiness Patriarch Pavle of Serbia When the brotherhood of Rača Monastery grew and became stronger—both spiritually and economically—with seven monks and more than a dozen novices and students of the monastic school, it caused sharp aversion and even fear among the employees of the Udba.[1] The communist authorities couldn’t allow the Church and monasteries to live in prosperity—they only needed to present the image of it at best. When the authorities noticed the wonderful products produced by the monastery brotherhood being sold in the city market, they immediately decided to put a stop to it. They were particularly indignant about the brotherhood’s refusal to hand over liturgical items and vestments from the ancient sacristy to the museum at their demand. They called the novices, Abbot Julian, and Fr. Pavle into the Udba for questioning. They asked what right they had to gather young people in their monastery, abuse their trust, and use them as labor, which is strictly forbidden in the country of victorious socialism, and they were given the strictest punishment for violating the socialist rule of law.

His Holiness Patriarch Pavle of Serbia When the brotherhood of Rača Monastery grew and became stronger—both spiritually and economically—with seven monks and more than a dozen novices and students of the monastic school, it caused sharp aversion and even fear among the employees of the Udba.[1] The communist authorities couldn’t allow the Church and monasteries to live in prosperity—they only needed to present the image of it at best. When the authorities noticed the wonderful products produced by the monastery brotherhood being sold in the city market, they immediately decided to put a stop to it. They were particularly indignant about the brotherhood’s refusal to hand over liturgical items and vestments from the ancient sacristy to the museum at their demand. They called the novices, Abbot Julian, and Fr. Pavle into the Udba for questioning. They asked what right they had to gather young people in their monastery, abuse their trust, and use them as labor, which is strictly forbidden in the country of victorious socialism, and they were given the strictest punishment for violating the socialist rule of law.

The abbot and Fr. Pavle answered:

“They are the monastery’s novices and students. They’re preparing to become monks. We monks have a rule: You have to work to live. So we’re working.”

“What students?! Where are the classes, where are the teachers, where is the permission?!” the chief of the Udba and the other interrogators shouted.

“And where was the school of Haji Melenty[2] and his monks?” replied Fr. Pavle. “They had an Horologion to learn and a hoe to work and earn their bread! It’s the same now: Our monks and novices aren’t hirelings, but honest laborers, working conscientiously.”

The interrogators were well aware that not only Rača, but all the monasteries in general could be closed under the pretext of not having a normal school at the monastery, but they came up with something worse: They raised the tax on the monastery from 75,000 to 350,000 dinars—a terrible amount—so all possible profits would just go towards paying the tax—and that’s what happened. Additionally, some of us were simply physically unable to cope with the new requirements. We had to sell our cattle to pay the tax, and the students and novices were forced to leave the monastery due to the pressure on them. And then laudatory articles appeared in the press about how well they work in the monastery and how diligently they manage their property… The monastery brotherhood was soon completely impoverished.

The beginning of his ministry in Kosovo. First concerns, jokes, and… wounds

In 1957, Fr. Pavle became the bishop of Raška and Prizren and he moved to Kosovo and Metohije. We went to congratulate him in Prizren. After the enthronement, all the guests went to the ruins of the Monastery of the Holy Archangels. The Albanian children accompanied us, shouting after us: “Pop, Pop, go hang yourself!”[3] and so on, and none of the Albanian adults even tried to put a stop to this shameful behavior.

When the guests left, I stayed to help Vladyka Pavle set up his accommodations in the seminary building in Prizren. The next day, I saw Vladyka on the stairs changing light bulbs and sockets. I asked him jokingly:

“What will you do, Vladyka, if someone comes here now looking for the bishop to congratulate him and take his blessing, and the bishop is in the stairway changing light bulbs?”

“It’s all right, I’ll ask him to join me—he does the same work at his own place. We’ll get to know one another and talk while working, and it will be a blessing,” Vladyka Pavle calmly replied.

That’s how he always was. When he had free time, Vladyka was always repairing or correcting something—shelves, cabinets, decorating the church, liturgical books. Such work is very useful when you have to think carefully about what you will write or say in a homily.

Vladyka worked hard to restore ruined churches in Kosovo and Metohije. In addition, he paid the closest attention to endowing empty parishes with good, zealous priests, and improving the lives of the clergy. Given that he had no car (Vladyka was against any “luxury,” which a car was at that time), he would take a suitcase in hand with his vestments and either go by bus or train, or he would walk on foot to a church or a monastery where there was no priest yet. And he would sometimes jokingly call me “the flying messenger,” because he would also send me to various villages to serve Liturgy or other services.

I remember one time after Liturgy in Gorioč Monastery, thirty children were baptized. Everyone was with their Godfathers—their kumbaris. But one of the kumbaris was definitely mentally ill. When during the Baptism the Godfather answers for his Godchild that he renounces satan and all his works, that he unites himself to Christ, and so on, everyone clearly answered with awareness of what was happening, but with this one was a howl like “n-n-n”—what kind of Godfather is that? I asked people who he was. The parents of one child said that, “This is how it traditionally is—his father was a good parent, and this is his heir, and it’s not acceptable to change the kum.” I had to insist that a healthy person take his place, because the Sacrament requires understanding and cooperation with the priest.

The altar in the church at the Monastery of the Holy Archangels

The altar in the church at the Monastery of the Holy Archangels

It should be noted that in those years, in the mid-1960s, there were many Orthodox Serbs in Kosovo and Metohije. The villages were full and children were everywhere. And not only Serbs came to the services, but also Albanians, especially on big feasts. Some of them worked in the monastery fields, and there were no problems. But as soon as Tito changed the policy regarding Serbian Kosovo, the troubles immediately began: The Albanians realized that they had been given the “green light” and could now persecute the Serbs, forcing them to leave, so they could build their own “Albanian Kosovo,” and all under the hypocritical slogan of “brotherhood and unity.” From that time on, no Serbs, including priests, could freely and peacefully move about our region. They would throw stones and mud at us and insult us. The students of the Prizren Seminary were constantly attacked with knives, broken bottles, clubs with nails, and the like. They also attacked the convents and tried to rape the nuns. Vladyka Pavle was attacked right in Prizren, on the bridge in the center of the city. Some impudent young man ran up to him and began to pull on his beard. Vladyka pushed him away and continued walking towards the post office to send off some letters. The Albanian waited for Vladyka to come out of the building and hit him hard on the back of the head with some object. He fell unconscious, covered in blood. People nearby called the ambulance and the police. The attacker was found a few days later, but he wasn’t punished at all—a common occurrence in Kosovo.

The Monastery of the Holy Archangels

The Monastery of the Holy Archangels

Another time another person hit Vladyka, knocking his kamilavka off his head. Seeing this outrage from afar, a Serbian policeman ran over, picked it up, and ran after Vladyka to give it to him.

I was lucky once: A kamilavka made of strong paperboard saved me from a severe wound—there was no blood, but I nearly lost consciousness. There were thousands and thousands of such instances.

“Don’t get involved in politics, Vladyka!”

Soon about 700 (!) Serbian villages were inhabited by Albanians. Our churches were left without parishioners, and we bore witness to a terrible sight: The warden of a church handed the keys over to the bishop, saying: “The church is empty—no one comes anymore. There are no more Orthodox in this village.” Then Vladyka Pavle went to Belgrade to inform the Synod of the catastrophic situation. The Synod decided to send Vladyka Pavle to meet with Marshal Tito, at which the bishop would acquaint the head of Yugoslavia with the actual situation in Kosovo and Metohije. When Vladyka told him about the murder of Serbs, of their persecution by the Albanians, Tito replied:

“Vladyka, don’t get involved in politics and its problems; it’s none of your business. We have our people in Kosovo; they inform us about everything on a daily basis. All is fine in Kosovo.”

Even before going to Belgrade to meet with Tito, Vladyka Pavle realized that he had to face the truth: There would be no help. In any case, the Albanians accused the Serbs, implying that it was not they who were killing, persecuting, and torturing the Serbs, but to the contrary—the Serbs them. They also accused us, priests and monks, when they were smashing our heads, when they were persecuting us. Thus, “thanks” to Tito and the communist authorities, they presented themselves as victims of “Greater Serbian nationalism”—and later “thanks” to the U.S.A. and NATO too. In the forty years I spent in Kosovo and Metohije, I never saw or heard of a Serb attacking an Albanian at night or from around a corner, while they were killing the Serbs by the hundreds—whether civilians or policemen. The strange long-suffering of the state ended only when the soldiers posted at their barracks began to be killed.

The Patriarch’s prayer

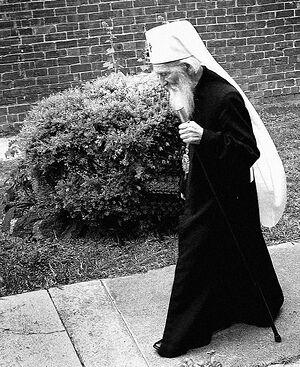

Patriarch Pavle What is man without God, rationality, and God-given freedom? What is a family without them? What do villages, cities, states, and all of humanity mean without all this? Without them, what are America and Europe with their visa-free passports? Without rationality, without God-given freedom, everything will be turned into slavery—that slavery that our Kosovo, consecrated by St. Sava, Prince Lazar, and many other holy hierarchs and martyrs from the day of the sacrifice of St. Lazar and his army until our day, is now experiencing. We can “thank” America and American Europe, as well as our politicians and leaders, our ignorance, our spiritual immaturity, and our irresponsibility for such slavery.

Patriarch Pavle What is man without God, rationality, and God-given freedom? What is a family without them? What do villages, cities, states, and all of humanity mean without all this? Without them, what are America and Europe with their visa-free passports? Without rationality, without God-given freedom, everything will be turned into slavery—that slavery that our Kosovo, consecrated by St. Sava, Prince Lazar, and many other holy hierarchs and martyrs from the day of the sacrifice of St. Lazar and his army until our day, is now experiencing. We can “thank” America and American Europe, as well as our politicians and leaders, our ignorance, our spiritual immaturity, and our irresponsibility for such slavery.

Patriarch Pavle prayed for Kosovo and for our entire homeland, for all the people, old and young, at every Liturgy, in every appeal to God. As long as he was able, he spoke and reminded secular and ecclesiastical people—the whole of the people—about this. Then he departed to God the Creator and Almighty of the entire world in firm faith that He will save us. During his earthly life, the powerful of this world, the national leaders often paid due attention to his words, pleas, and prayers. But our holy Church will wait for God’s judgment from Heaven with the patience of rational people.

To be continued…

[1] The Yugoslavian equivalent to the KGB.

[2] Bishop Melenty (Stevanović)—a national hero of Serbia, one of the leaders and organizers of the First Serbian Uprising, and abbot of Rača Monastery in the nineteenth century.

[3] “Pop” is a derogatory term for a priest.—Trans.