The Church of St. John the Evangelist in the village of Sidorovichi, the Ivankov district of the Kiev region.

The Church of St. John the Evangelist in the village of Sidorovichi, the Ivankov district of the Kiev region.

The village of Sidorovichi is situated close to the Exclusion Zone, an area with a 19-mile radius surrounding the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, where the radioactive contamination from nuclear fallout is highest and inhabitation is illegal due to the ecological catastrophe resulting from the disaster of April 26, 1986. Even the large part of the population in the villages surrounding the disaster zone has moved elsewhere. Sidorovichi, once a prosperous village of the Ivankov district in the Kiev region with a flourishing Soviet collective farm, was included in this zone too. Now deserted, with overgrown fields and a ruined livestock farm, the village numbers around 100 inhabitants, mostly old people who live out their days here…

The church of my childhood

The wooden church in honor of St. John the Evangelist, which was built in 1896 and miraculously survived the Soviet-era persecutions, remains the main attraction of Sidorovichi.

I remember this church from my childhood, long ago in the 1960s, when our parents would take my sister, elder brother and me to the village on summer holidays, to a log hut with a thatched roof. In the autumn, winter and spring the hut was boarded up all over because its owner, our grandma’s sister, was dead. Our grandma was born and spent her childhood in this village. She became an orphan early on, her brothers were killed in the First World War, and her parents died before the Revolution. In summer evenings by a kerosene lamp, after enjoying fresh milk with fresh brown bread, we would listen to granny’s stories about the terrible times of the early twentieth century when the world was being shaken by wars and revolutions, when people were dying of hunger, and about the beginning of the Great Patriotic War [the Russian name for World War II.—Trans.] She told us how Fyodor, her sister’s husband, was blown up by a mine, how they used to walk twenty miles in search of something to eat and exchange clothes for food.

When our grandma was young, she sang in the church choir. Our hut stood some 110 yards from the church. I remember how at sunset, the sun reflected in the church windows, making it seem as if reddish-gold flames were burning there, and angels of God with golden wings were celebrating Vespers…

I remember how the village would become silent on Sundays—there was not a sound. The unpainted floor of our hut was washed and cleaned, the fire in the stove was kindled, the Sunday pie was cooling off under embroidered rushnik towels, and there would be a bunch of wild flowers by the old icon of the Nativity of Christ. We would wait for our parents to arrive. People from the neighboring villages of Zhmiyovka, Polidarovka and Olizarovka would hurry into the church. Women would walk barefoot, carrying their shoes in their hands to prevent them from gathering dust. They would sit down on the grass near our fence while talking in hushed tones, put on their stockings and leather slippers, set their headscarves and calico dresses straight, and “march” towards church while making the sign of the cross and repeating: “Lord, forgive us! God, help us! Queen of Heaven, be with us!”

Grandma didn’t take us to church, most likely in order to avoid a getting a talking-to from our Communist father who, I think, would not have objected anyway: he was good-natured, compliant and never imposed his opinion on others. Granny recollected how in the 1920s, the Communists tore the crosses down from the church roof, how the bust of Tsar Nicholas II, installed by the church, was taken away, and how a “CLUB” sign was nailed to the entrance.

During World War II, the church was reopened and services were celebrated from then on. I remember how the death of one of the villagers was announced by a specific ringing of the bells. Trying to explain its meaning, granny would repeat in time with the ringing: Buv-da-vmer-buv-da-vmer1… That was a bit scary. Then horses, pulling a cart covered with sackcloth, would bring the coffin with the deceased in it. And then the old priest, in white and gold vestments probably as old as he was, would come out, cross in hands, and lead the villagers in singing the Trisagion hymn, “Holy God…” The procession would move on the sandy road towards the graves—a cemetery in the pine wood at the entrance to the village.

These bright summer scenes, like others from my distant childhood, were engraved in my mind forever like unfading colored slides: once you pull one of them out from the “archive” of your childhood, it becomes filled with new contents, acquiring colorful details, sounds and even smells…

It is no coincidence that Fyodor Dostoevsky concluded his enduring novel The Brothers Karamazov with a monologue of the main character, Alyosha Karamazov, who addressed the other boys after the funeral of their classmate Ilyusha, the son of the unhappy Staff Captain Snegiryov:

“You must know that there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and good for life in the future than some good memory, especially a memory of childhood, of home. People talk to you a great deal about your education, but some good, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man carries many such memories with him into life, he is safe to the end of his days, and if one has only one good memory left in one’s heart, even that may sometime be the means of saving us…2”

Perhaps we too, the children of the 1960s, who heard the echo of the war all around us, and despite the horrors of that period, inherited beautiful memories that can be defined by one word: happiness. Because the souls of children, which aren’t stained by sin, see the world in a kaleidoscope of bright colors and radiant feelings, perceiving all people as good, with love reigning in their hearts…

Half a century later

It’s horrible to think about it, but half a century has passed since then… Granny is long gone, my parents are no longer on this Earth, and my grandchildren are growing. I can’t help but recall the words of an old Ukrainian folk song, “There is a High Mountain” that granny sang when she relaxed:

Do not cry, dear pussy-willows,

Spring will return, will return,

But the fine young man will not return,

Neither will the years return…

I came to my ancestors’ native village in the autumn of 2020. I hadn’t been there for decades. Actually, there had been no one to visit here. We children grew up, our grandma grew old, and our hut was bought for a song by our neighbor. Life went its own way. When I had started serving in the Church as a deacon, I found a photo of our old church online and trembled as I recognized it in the ring of old birch trees. I found out that it is still active, although the village has almost died out… I also found the phone number of the priest who serves there, Fr. Alexander Dovgan, and we agreed to meet.

Getting off the bus, I barely recognized this long-forgotten place.

The pine plantation at the entrance to the village had turned into a pine wood, and the sandy central street had been paved.

I saw a new village hall, which must have been built in the 1970s (we kids would run to the old wooden one for children’s shows, and each ticket cost 5 kopecks3), with a monument to the unknown soldier erected beside it and a memorial plaque in commemoration of 160 fellow-villagers killed in World War II. To my amazement, the hall was open: I entered the cool, empty space of the library and met the librarian Tatiana Mukhoid.

It turned out that Tatiana also assists Fr. Alexander: she reads and sings in the choir, contributes to the district’s newspaper, writing about the history of Sidorovichi and the lives of fellow-villagers. One of them, Nehemiah Rabin (1886—1971), as an eighteen-year-old teenager emigrated to the USA seeking a better life, then fought in the First World War in the British Army and afterwards became a prominent public and political figure of Israel and the father of Yitzhak Rabin (1922—1995), the fifth Prime Minister of Israel.

The librarian Tatiana Mukhoid.

The librarian Tatiana Mukhoid.

Another great native of Sidorovichi was Anton Grigoryevich Zabrodsky (1899–1989), a Ph.D in Technology, a professor, an awarded scientist and engineer, a food technology specialist in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. There were a bundle of other celebrated workers and military men from Sidorovichi. Photographs of various years are displayed at the library stands.

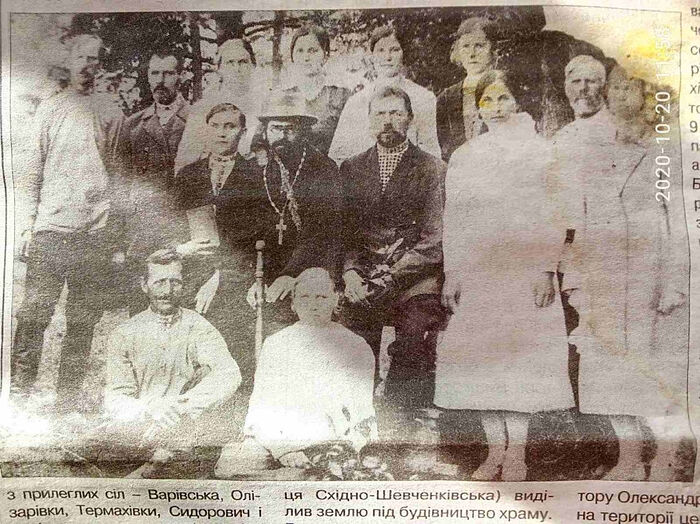

The parish of St. John the Evangelist in Sidorovichi. A photo of the 1920s.

The parish of St. John the Evangelist in Sidorovichi. A photo of the 1920s.

Before the revolution, when Sidorovichi was part of the Radomyshl District of the Kiev governorate, my great-grandfather Ilya Chapovsky (the father of my grandma, Tatiana Ilyinichna, whom I spoke of before), lived in the Shlyakhta rural area. He was involved in founding the village Church of St. John the Evangelist and died in 1913, shortly before the revolution. Prior to the Revolution of 1917, the village had a parish school and the main hospital of the district. In the Soviet era, a new “eight-year school” (providing the first eight years of school education) was built. There was a district hospital, a maternity ward for twelve nearby villages, along with a pharmacy, a post-office, four grocery stores and other shops. There was a large livestock farm in the May 1st Collective Farm; flax, potato, beetroot and other agricultural produce were grown on its fields. After the collapse of the USSR, the collective farm ceased to exist. The fields were overgrown with weeds and trees. The post office, hospital and maternity ward, and later even the school were closed.

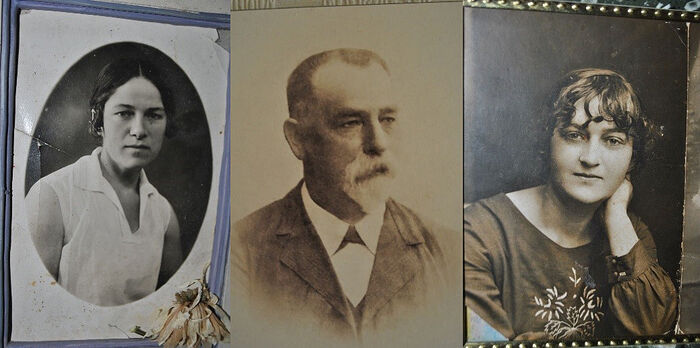

The Sidorovichi residents who witnesses the building and opening of the church: Ilya Chapovsky and his daughters, Maria (1899—1957) and Tatiana (1903—1984).

The Sidorovichi residents who witnesses the building and opening of the church: Ilya Chapovsky and his daughters, Maria (1899—1957) and Tatiana (1903—1984).

Feeling blue, I plodded towards the site of our village hut. The librarian Tatiana told me that the hut had been burned down long ago and now there was just a vacant lot. I found it in the overgrown brush, and among the trees I saw the remains of the chimney, along with the old withered apple-tree, under which there used to be a table and a children’s swing. Having prayed for my reposed relatives, I headed toward the church that called me with its blue silhouette and the gold yellow cross on top of the dome.

In sorrow, I saw the remains of the chimney and an old withered apple-tree.

In sorrow, I saw the remains of the chimney and an old withered apple-tree.

Fr. Alexander

Anxiously, I opened the church gate and lingered by the steps leading to the church porch. The autumn wind was rustling in the leaves of the old birch trees. I noticed that most of the ring of birch trees that had once surrounded the church had disappeared, and the few surviving dying trees were waving their branches, as if trying to say: “Well, hello there. Why haven’t you come for so long?”

“Well, I came…” I whispered in reply, made the sign of the cross and opened the heavy church door.

To my surprise, the church interior was resplendent with its bright paintings, like a Paschal egg. A ray of sunlight pierced sideways through the church space and fell directly onto the central icon of St. John the Evangelist.

The bright colors of the paintings, coupled with the words of the akathist hymn sung by the priest, filled my heart with ineffable joy, as if someone said distinctly, “There is no death! There is everlasting joy!” In confirmation, the beautiful words of the akathist resounded:

“Rejoice, ray of the noetic Sun:

Rejoice, radiance of the Unsetting Light!

Rejoice, lightning that enlightenest our souls:

Rejoice, thunder that terrifiest our enemies!4”

An hour later we were drinking tea in Fr. Alexander’s small church lodgings, where he has lived for twelve years. While examining his “mansion” that resembled the hut of a rail worker, with paper bags hanging on hooks everywhere “to stop the mice from getting to them,” I couldn’t stop marveling at his ascetic way of life. I imagined winter nights with blizzards, with a lonely street lamp outside the church swinging in the wind, the chilly church where he goes every morning in the dark to perform his monastic rule with the midnight service, the hours, canons and the akathist. The altar on the right side of the church is partitioned by a plywood wall—in winter Fr. Alexander heats the stove there because it is impossible for him to heat the entire church. I recalled episodes from the lives of Athonite ascetics who struggled in their kalyvas in solitude, far away from monasteries, and I thought, “Mt. Athos, the Solovetsky Islands, and the Optina Hermitage are here, at the same time!”

“Fr. Alexander, how do you live in such conditions? Do you cook for yourself?”

“Sure, I do it myself. I also bake prosphora myself in the other half of my ‘chamber,’” the priest smiled. “I’ve gotten used to it. After all, twelve years aren’t the same as twelve days.”

During our unhurried talk I learned that Fr. Alexander was born in 1967 in what is now the Altai Republic [within the Russian Federation, in the west of Siberia.—Trans.] to a working family, and then his parents moved to Uman in Ukraine where now they live out their days. It was there that Alexander Dovgan graduated from an eight-year school, studied at the Technical College of Agriculture and then was drafted into the army—not just anywhere, but to Moscow—to the Interior Ministry’s special unit that guarded the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at Staraya Square.

“That was an amazing period of my life,” Fr. Alexander recounted excitedly. “While on leave, I, a soldier from a Ukrainian province, was lucky enough to stroll around Moscow, visiting museums, churches and arts and crafts exhibitions. Then I began to think about the purpose of life for the first time. If there are churches, and they have stood for centuries, then God dwells in them…”

After two years of service, he was offered extended military service. Why not? Here he had Moscow, the dormitory and a salary. So he agreed.

One day he stood through a Lenten service at the Theophany Cathedral in Yelokhovo and then walked as far as the Pushkinskaya metro station, where there was a spontaneous book sale. There he saw a man selling a copy of the Bible. Alexander inquired and the man charged 100 rubles for the sacred book—an astronomical amount for that time. But Alexander took out his savings in rubles from the pocket and bought the long-awaited book, which he then read through the night.

“After reading the Old and the New Testaments, the Acts and the Epistles of the Apostles, I understood very clearly that I must follow Christ, just as His disciples did… I handed in my resignation and came back to my homeland, to Uman,” the priest proceeded. “There I got a job at a factory as an engineer and assistant head of the equipment department. One day at a local church, the choir director approached me and suggested that I sing in the choir. I agreed and later began to help the priest, Fr. Peter. As part of my work, I would often travel on business, and wherever I travelled I always tried to visit churches. A hieromonk at the Kiev Caves Lavra said to me during confession, ‘Do you wish to become a priest, brother?’ I was baffled. I had never considered anything of this kind. ‘Then go to your local priest and talk to him on this matter,’ he said gently and blessed me. I won’t dwell on my twists and turns of life that followed, how I intended to marry but was unsuccessful because it was contrary to God’s plan for my life. I quit my job at the factory and after struggling to find a suitable monastery, I ended up at the Diocese of Vinnitsa—at the Holy Trinity Convent in Brailov, to which Metropolitan Macarius (Svistun; †2007) of Vinnitsa sent us candidates for the priesthood to help reconstruct it. It was he who ordained me as a deacon and then as a priest. I served in some parishes of the Diocese of Vinnitsa and later in the Diocese of Kiev for several years. I tried to get obediences in some monasteries in Kiev, but things didn’t work out for me. And in 2008, I was sent to this faraway village… And I thank God.”

“How do you survive, father, if you barely have ten people at services?”

Fr. Alexander and his “kalyva”

Fr. Alexander and his “kalyva”

“I manage somehow,” the priest smiled. “The Lord doesn’t abandon me. Hermits subsisted on grass, and St. Seraphim of Sarov ate wild masterwort. As for me, I have my own vegetable patch, and some generous people gave me a Zhiguli [a Soviet and Russian car brand produced between 1970 and 2012.—Trans.]. I take care of it just like a shah grooms his Arabian stallion. Everything would be fine, but the church needs to be saved. This church of God is in a very bad state,” the priest ended his story on a sad note.

And we headed there again to say the lunch-time prayers.

In the church

I venerated the icons and looked at the simple paintings on the old church walls. Everything about the church had an old feel about it. This church has stood here for 124 years, surviving world wars and revolutions, militant atheism and the Khrushchev-era persecutions, Gorbachev’s perestroika, the Chernobyl disaster, and the collapse of the Soviet Union… How many baptisms and funeral services must have been performed here! I struggled to find the graves of my grandma’s sister, Marusya, and her husband Fyodor who had been blown up by a mine during the war. As a boy, I would visit their graves with my grandma, but the cemetery has grown over these fifty years and I couldn’t find the graves of my relatives. I recall a wooden cross on my grandfather Fyodor’s grave, painted green, with the inscription, “Passerby, remember my ashes. Now I am home, but you are a guest.”

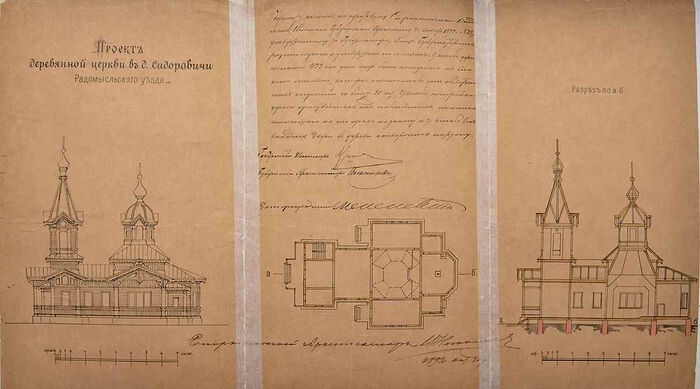

Fr. Alexander pointed at the ceiling and the decayed beam that holds it up. He also showed me a copy of the old designs of the church, dated 1882 and signed by the governorate’s administration and the local bishop. The church was decorated with high domes, both on the bell-tower and on the central cupola. According to the stories told by the old-timers in the village, the domes and crosses had been removed before the war when the church was turned into a club.

The design of the Church of St. John the Evangelist.

The design of the Church of St. John the Evangelist.

“The roof leaks in five places, and the wall has rotted through from the north side where the sunshine can’t reach,” The priest pointed at the damp wall. “People help me, so we are filling in holes little by little from the inside and from the outside. God willing, we will survive the coming winter too… A commission from Kiev was here to take photographs and even make a film with drones; they promised help. But, as the saying goes, ‘one has to wait for three years for what is promised,’” the priest smiled again. “The Lord won’t abandon us, we believe that!”

***

Filled with sadness, I left the church of my childhood. “The Lord won’t abandon us, we believe that!” I recollected the words of the ascetic priest.

On the way to the bus stop I glanced back again. It was drizzling, and the shining corrugated iron church roof seemed to be reflecting the gray, weeping sky.

And the old birch trees were waving their branches to say goodbye, as if asking: “Will you come to us again?”

“I’ll definitely come back,” I said and walked along the village street.

For those who wish to help the church the author asked us to give the bank card number: PrivatBank of Ukraine 4149 4991 1319 2429 (Liventseva Ludmila Georgievna; the rector’s assistant).