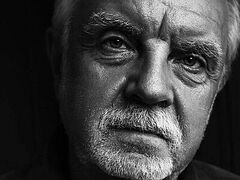

Since 1991, Fr. Luke has been the Assistant Director of the Iconography School and its Director since 1993. As of September 2, 2019, he is the Dean of the Iconography Faculty of the Moscow Theological Academy.

—As time goes by, iconographic canons change, so you wouldn’t confuse the style prevalent in the fourteenth century with that of the seventeenth century. What was new in the iconography of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? In the images of new saints?

—Art is always a reflection of its time. It’s another matter when artists began, in the sixteenth century, to look back to images of the past. Obviously, some icons were created with an eye at a particular historical period. It is inevitable when a painter with knowledge and experience begins to create his own original works.

In the twentieth century, icons brought many people to the Church. Our school’s specialty is mastering the experience of ancient times. The depth of Orthodoxy and culture influence a person through an icon on conscious and unconscious levels, even if he doesn’t understand everything.

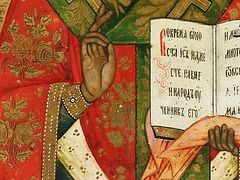

When painting icons of the holy new martyrs, there are iconographic questions about symbolism, clothing and resemblances that arise. An icon should have a connection with its prototype, and that connection can be lost if the face lacks similarity. It is difficult to pray before a badly painted and unrecognizable image. Think of the icon of the Holy Hierarch Nicholas. All of them differ so much! At the same time, we can always recognize him, even if we cannot read his name. It is because there is an understanding of his personality, one that has formed through the centuries. In this respect, it isn’t easy to paint an icon of a new saint well.

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with their lack of attention to the theology of icon and to the narratives of clothing and attributes, had a ripple effect on the modern iconography. The icons of today may come ill-designed in a way. I think the icon of “The Chernobyl Savior” is a complete failure. I don’t like any of the icons of the Mother of God “Resurrecting Rus’.” And not only because it has a dubious source, but also because the icon’s very concept raises questions. We see the Mother of God and a lot of churches below her, but no people. What are these churches for? Who are they for? We have an ultimate goal, the resurrection of the human soul. In this sense, this icon is unsuccessful.

Beginning from the second and third year of study, the students at School are given assignments to create an independently conceived icon. We see new icons being produced today. The iconographers seek inspiration from ancient images and then create their paradigms in graphics, drawings and color systems.

I don’t see any fundamental developments in today’s art. The artists of the twentieth century got as far as negation, down to [Malevich’s—Trans.] “Black Square” and exalted performance art. An artist who strives to create uplifting art as his goal will have to, one way or another, rely on the experience of previous generations. So, whether a secular or a church artist goes through the process of reinterpretation of that experience, it still involves him keeping in line with the tradition.

—Do you agree that the “Black Square” was a revolution in world art?

—I wouldn’t like to dwell on this topic. In short, I think it was the destruction of art. Of course, it has meaning. However, instead of bringing forth beauty, this canvas works as a destructive force. Few people understand this. There are too many emotions involved.

—What stands in the way of modern church art?

—Haste. Determination to do things as cheaply and quickly as possible. A declining level of artistic training and of culture in general.

Discussion at the preview session. 2018

Discussion at the preview session. 2018

—Is there any creative rivalry among your students the iconographers?

—Things are different here. It’s not about competition. Of course, when someone shows better results, the others try and catch up. Our students are like one living organism, a family where one person’s successes help the others. Your neighbor’s luck inspires, brings joy and helps others to achieve the same. When it’s time for our students to defend their final projects, iconographers from Moscow, the surrounding region and even from farther away come to see the projects and cheer on their brothers and sisters.

—We live at a time when we don’t do any long-term planning. There is hope that, after all the restrictions are lifted, life will return to normal, your graduates will come to celebrate the Iconography School’s graduation ceremony, and we will have an opportunity to have another conversation.

—I hope that all of us will soon come together for the defense of this year’s graduates’ final projects and wholeheartedly rejoice at their success.

The final project defense. 2019

The final project defense. 2019

Olga Lunkova

spoke with Archimandrite Luke (Golovkov)

Translation by Liubov Ambrose

A few more words about Archimandrite Luke

Margarita Proskurova, class of 1994:

—Over the winter break during Fr. Luke’s first year as director of the Iconography School, he took a group of students to the Pskov Caves Monastery. Elder John (Krestiankin) immediately blessed Fr. Luke to concelebrate the Liturgy with him and later warmly greeted all of us in his cell. He was asking about the school and joked a lot. Then he generously blessed everyone with holy water, with Fr. Luke getting the biggest share, leaving him soaking wet. The elder told the students, “You have such a humble man as your director!” The rumors are that Fr. John told Fr. Luke to act not like a director, but more like a father figure, or even like a “mother” to his students. Fr. Luke has obediently done so for over a quarter of a century, and his students have felt and continue to feel it to this day.

Anna Gorodianenko, class of 2000:

For modern people, used to comfort and unaccustomed to any deprivation, my story might seem either useless or out of touch with reality. When you speak about the Iconography School at Moscow’s Theological Academy, you wonder what made (and makes) it is so different from other theological and secular schools? I entered the Iconography School at the end of the turbulent 1990s. Keep in mind that the people of the 90s hadn’t been spoiled. There was no endless stream of entertainment, no exotic foreign food, not even parental love. Such circumstances probably helped us advance on our spiritual quest and bring questions of spiritual values front and center. People began to see more value in that which he is given: the first glimpse of the morning sun, the oddly-sized wool felt boots, a cup of a hot tea or a warm greeting from a friend…

Nun Athanasia (Ivanova). The Synaxis of the Saints of Lipetsk. 2012. There were 70 of us living at the Iconography School at the time of my enrollment. Now, as a mother of four children, I realize the great responsibility of having young people in your care, regardless of whether they are young children or adult students. What did we need most? Nothing but love, of course! Love that is neither arrogant nor insists on its own way, neither irritable nor resentful, does not rejoice at wrongdoing but rejoices with the truth, it endures all things and, of course, never ends.

Nun Athanasia (Ivanova). The Synaxis of the Saints of Lipetsk. 2012. There were 70 of us living at the Iconography School at the time of my enrollment. Now, as a mother of four children, I realize the great responsibility of having young people in your care, regardless of whether they are young children or adult students. What did we need most? Nothing but love, of course! Love that is neither arrogant nor insists on its own way, neither irritable nor resentful, does not rejoice at wrongdoing but rejoices with the truth, it endures all things and, of course, never ends.

Father Luke, the director of the Iconography School, bore this love and dispensed it. At first glance, you couldn’t tell, as he looked like any other administrator, in other words, the man in charge. Father used to speak of himself in the third person, “Who will think on your behalf? The director?!” On the other hand, he has unique gifts: you simply can’t hide anything from him. I was always shy (and I still am!) when under his scrutinizing glance because the director is the one who knows everything about everyone.

Dedication to iconographers. 2018. Father’s third unique quality was his ability to always show up at the wrong time—whether it was when we were drinking tea instead of studying in the workshop, or during heartfelt revelations among the sisters (and father would come down from the second floor right when important revelations were taking place on the first floor). On the other hand, whenever anyone was overcome with melancholy, that person would bump into the director, who with a wave of his hand would invite him for a heart-to-heart talk. No one left those conversations without consolation. Father knew how to rejoice with those who rejoiced and how to weep (in the literal sense of this word) with those who wept.

Dedication to iconographers. 2018. Father’s third unique quality was his ability to always show up at the wrong time—whether it was when we were drinking tea instead of studying in the workshop, or during heartfelt revelations among the sisters (and father would come down from the second floor right when important revelations were taking place on the first floor). On the other hand, whenever anyone was overcome with melancholy, that person would bump into the director, who with a wave of his hand would invite him for a heart-to-heart talk. No one left those conversations without consolation. Father knew how to rejoice with those who rejoiced and how to weep (in the literal sense of this word) with those who wept.

Thanks to his wise guidance, I easily found my career path, but that is a topic for another volume of my memoirs. I don’t believe I am the only one. I also want to add that the job of managing the souls of the artists (in other words, incredibly ambitious eccentrics) isn’t for the faint-hearted—watch out or you might go crazy yourself! Thanks to the care of the director, we felt part of one family, a motley crew of brothers and sisters united by a sense of true brotherhood and sisterhood. Everyone around would confirm that. The choir department students used to envy us, “Father fusses over you like a hen with her chicks.” It was true.

I can remember one weekend pilgrimage trip with father. A line of brightly dressed iconographers stretched from the Lavra to a scenic overlook across the highway, moving toward the railway station. Father Luke, at a rapid-fire pace, ran ahead of us to count his chicks. As we reached the ticket counter, we hear his voice, “Seventy children’s tickets!” Deep voices retort from behind his back, “But father…!” He retorts back, “But you are my kids!” His words echoed in my soul long after the trip was over. It echoes in response to the dissatisfied looks of my own adolescent children, overwhelmed at my excessive motherly concern for their wellbeing.

The Synaxis of the Saints of Moscow Theological Academy. Anna Korchukova. 2018. oIt was winter and the temperature plunged to -33° C (-27° F). Some of us who came from Moldova and Ukraine had trouble adjusting to the freezing weather. I had to settle for a three-day stay in the isolation ward with a diagnosis of vegetovascular dystonia. When my three-day stay was over, I hurried to father, and found him distributing warm clothes left behind by the school’s graduates of previous years (I’d like to point out specifically to the young people today that we were not at all concerned what brands of shoes or clothing we were wearing). I was stuck behind the backs of my male classmates. Father pulled out a pair of wool felt boots, a real luxury! The guys in front of me impatiently waited for this happy lot to fall into their hands but father warned, “These are a women’s size! Brothers, they are for women!” The sunny winter day suddenly got warmer when I put on my new boots. It was hard to walk in them, but I brushed off any thoughts about it. I smiled, and then I saw father coming the path. “How do they feel?” he asked. My blissful smile was the best answer. “Almost like home, right?” he said, walking away, and my heart skipped a beat for a moment at the thought of home. My home today was now here, at the Iconography School. And the care I felt there is something every student felt, I can say that with certainty.

The Synaxis of the Saints of Moscow Theological Academy. Anna Korchukova. 2018. oIt was winter and the temperature plunged to -33° C (-27° F). Some of us who came from Moldova and Ukraine had trouble adjusting to the freezing weather. I had to settle for a three-day stay in the isolation ward with a diagnosis of vegetovascular dystonia. When my three-day stay was over, I hurried to father, and found him distributing warm clothes left behind by the school’s graduates of previous years (I’d like to point out specifically to the young people today that we were not at all concerned what brands of shoes or clothing we were wearing). I was stuck behind the backs of my male classmates. Father pulled out a pair of wool felt boots, a real luxury! The guys in front of me impatiently waited for this happy lot to fall into their hands but father warned, “These are a women’s size! Brothers, they are for women!” The sunny winter day suddenly got warmer when I put on my new boots. It was hard to walk in them, but I brushed off any thoughts about it. I smiled, and then I saw father coming the path. “How do they feel?” he asked. My blissful smile was the best answer. “Almost like home, right?” he said, walking away, and my heart skipped a beat for a moment at the thought of home. My home today was now here, at the Iconography School. And the care I felt there is something every student felt, I can say that with certainty.

The Synaxis of the Saints of Damascus. Konstantin Shatkov. 2017. Fifteen years after my graduation, I was helping my husband with an order in the iconography studio, which is next to the Iconography School. Two student assistants couldn’t agree on how to carry a large table through the doorway. They immediately heard the director rushing toward them, “You’ve got no conciliarity!” I knew instantly that father hadn’t changed over all those years. He still shares the love that never ends. Without learning conciliarity, the students will never know how to carry a table inside or, what’s much worse, how to weather the trials of life. Our dear Father Luke is still the vessel of Christ’s love and his former “chicks” come together to drink tea and celebrate his name day. Father’s prayer is akin to a mother’s love: it helped us, and not just once, as we struggled in our lives.

The Synaxis of the Saints of Damascus. Konstantin Shatkov. 2017. Fifteen years after my graduation, I was helping my husband with an order in the iconography studio, which is next to the Iconography School. Two student assistants couldn’t agree on how to carry a large table through the doorway. They immediately heard the director rushing toward them, “You’ve got no conciliarity!” I knew instantly that father hadn’t changed over all those years. He still shares the love that never ends. Without learning conciliarity, the students will never know how to carry a table inside or, what’s much worse, how to weather the trials of life. Our dear Father Luke is still the vessel of Christ’s love and his former “chicks” come together to drink tea and celebrate his name day. Father’s prayer is akin to a mother’s love: it helped us, and not just once, as we struggled in our lives.

Father turned to me with a scrutinizing glance and I looked down in response. “Why is he looking at me like that?” I wondered. Well, it is because I have very little of that love that, according to the Apostle, never ends.

Galina Proskurova:

—My first memories date back to that blessed time when there was neither Internet nor social media. I believe that the creative atmosphere of the Iconography School has changed little since then. However, at that time we would enter a world dramatically different from the one around the School, and we had never witnessed anything like it before. It was a world fully immersed in iconography and the creative process, in worshipping, eating and praying together. It helped us come together and feel like a family. Of course, this had a lot to do with the personality of Father Luke, the School’s Director. He is an extraordinary man of living faith and love.

Then, there were our instructors! In general, anyone working at School was wonderful! I was lucky to study with A.V. Zdanovich, who cared for his students, and was capable of finding the key to every student’s heart, helping us discover our potential, and offered his support. This is extremely valuable for anyone studying iconography or any other subject.

I remember many things when the School comes to mind. There are many open sources of information about it, how it is run, or how to join its online courses. Much effort is exerted to make it accessible. Yet, it remains a special educational institution, with its unique environment and traditions. The quality of work produced there remains high in terms of the beauty of execution and spiritual content.

Maria Glebova, Senior Instructor at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University and the Surikov Art Institute:

—I studied at the Iconography School between 1992 and 1995. When I entered it, the School was very low-key with just two classes enrolled and Father Luke working as its Assistant Director. I was overwhelmed by the School’s warm and kind atmosphere that Father Luke worked hard at creating for us. I was surprised by his delicate and thoughtful attitude towards his students.

The Ladder of Divine Ascent. 2018. We never heard any reprimands or rebuffs and he always treated us with warmth, attention and tactfulness. This disposed us to behave well in response and helped us feel remorse for any bad behavior. Father Luke is particularly known for reasoning and admonishing us with silence and meekness.

The Ladder of Divine Ascent. 2018. We never heard any reprimands or rebuffs and he always treated us with warmth, attention and tactfulness. This disposed us to behave well in response and helped us feel remorse for any bad behavior. Father Luke is particularly known for reasoning and admonishing us with silence and meekness.

Father Luke has great organizational skills. At the time, we had students from all walks of life, some making the first steps into the Church and others bringing the years of secular life experience. To ease them into life at school, Father Luke would select the God-fearing and devout students and appoint them as the course leaders. He would give them assignments while they, so to speak, churched and taught their unchurched classmates. Later on, many of them stayed at the School working as Father Luke’s assistants. Gradually, the spiritual life at school was organized.

Father Luke, an artist by profession, took an active part in the creative process of iconography, supporting our artistic quest and innovations. The School’s proximity to the Lavra facilitated concentration, contemplation and the creative process, so we studied in the atmosphere of creativity and prayer. I have never experienced it since to such an extent. We were extremely happy to live near the Lavra in the friendly environment of our Iconography School. I view all graduates of the School as part of a family, since all of us feel this connection.

When I graduated from the Lavra’s school, I really wanted to stay and work there, but Fr. John (Krestiankin) blessed me to seek work in Moscow at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University. I became an iconography instructor there. It was quite hard at first and I would come to seek advice from Fr. Luke who helped me a lot by sharing his experience and wisdom. He offered some iconography samples for my students to copy. Later on, the School produced the icon study samples and supplied them to other recently opened iconography schools. It was akin to St. Sergius who sent his disciples throughout Rus’ after they had learned the foundations of monasticism and spiritual life. His disciples worked hard to nurture and enlighten our Motherland. And we, nurtured by the Lavra and our wonderful Father Luke, were able to go forth, and with the help of our mentors and education, spread throughout Russia and abroad and open new iconography schools and classes.