“Where’s Misha?”

In the fall, when yellow leaves were strewn about the monastery, several guests arrived: a mother, father, and a fourteen-year-old son. The parents had to go on a long business trip and they were worried about leaving their son with his grandmother. The thing was that their son spent all his time on the computer, refusing to sleep or eat. It was hard for his parents to get him to go to school, and he would always manage to escape back to his sole joy—the computer. They placed no hope in grandma anyways: She watched TV shows all day and lived vicariously through the characters’ adventures.

That’s how Misha—thin and lanky, with faded eyes and an unhealthy pallor—wound up in the monastery. He looked around the remote monastery in horror, and in his eyes lurked an unchildlike melancholy: He didn’t have his beloved computer here.

Abbot Savvaty attentively listened to the parents, looked at the depressed Misha, and allowed them to leave the boy in the monastery for the duration of their business trip. The school was six miles away, and they were already taking two students there—the children of a priest who lived near the monastery.

Misha spent the first days in a state of shock. He answered questions briefly and sullenly and was obviously harboring a dream of escaping. But he gradually began to come to life. Then he became friends with Novice Peter, who was the youngest in the monastery, having graduated from high school just a few years ago. And now the role of mentoring the youth warmed his soul. He generously favored Misha, and sometimes got carried away, frolicking about like a boy on par with his young charge. And a monk, Fr. Valerian, had the obedience of watching after both of them.

After class in the village school, Misha had obediences in the stables and fell in love with the monastery horse Yagodka.1 It seemed Yagodka was the first domesticated animal Misha had ever been close to. He took care of the horse with tenderness, to the surprise of the brothers. So they began to love one another, and a couple of weeks later, Misha and Peter began to take turns valiantly riding Yagodka around the monastery, although under the careful watch of Fr. Valerian.

Winter imperceptibly came to the monastery. And winters here were for real—not like in the city. Out here in the wilderness, on Mount Miteina, there were no neon advertisements or dazzling displays; there was no city hustle and bustle or dirty melted snow under foot.

Perhaps that’s why the stars shone unusually bright in the winter blue twilight, the white paths were surprisingly clean, and the dark dawn of the year was illuminated only by the light of the windows of the brothers’ cells. The frost and the winds, the snow and blizzards knocked on the monks’ doors, and then a fire crackled calmly and gently in the stoves, contending with the bad weather.

After their obediences, Misha and Peter started going sledding in the mountains. Peter was embarrassed at first: he, an adult—and a sled… Some of the brothers might see… Everyone would laugh at him. But none of the brothers even thought about making fun of him, and Peter gradually got hooked. And at the ringing of the bell, they would glide into the trapeza on a sled, covered in snow, rosy, cheerful, and hungry.

And everything was delicious, although it was the Nativity Fast. Monastic food is always like this, even if it’s fasting soup or pirozhki with water. The brothers cook with prayer—and that’s why it’s delicious. Rosy potato pastries or tender cabbage pirozhki, monastic fish soup and fish straight from the oven on Sundays—so fragrant! And then cranberry or lingonberry juice or tea with fragrant herbs, with raisin rusks.

The elder brethren ate little. Schema-Archimandrite Zacharias would eat a couple of spoonfuls of cabbage soup and nibble a piece of potato pie. Even Fr. Valerian, tall and broad-shouldered, ate little. They’ve been in the monastery for a long time. The abbot blessed Peter and Misha to eat their fill. And they tried.

The brothers had a tradition of making a manger scene on Nativity. Right by the church, in the midst of a winter snowdrift, was a lantern-lit ice cave, with a wooden manger inside, with real hay, and rag horses with a donkey and, most importantly—the Most Holy Theotokos with the Christ Child on a sheet.

It was especially nice to see this cave in the evening, when it was dark all around and the large stars were shining brightly in the sky. The hearth in the manger scene would shine especially gently, and the lanterns drew the eye and dispersed the surrounding darkness.

Fr. Valerian also brought a fluffy Christmas tree from the forest. Misha and Peter brought ornaments and icicles from the storage room, and the rain was shining. The ornaments were bright, with a crystal-clear chime. Misha would have never thought before that he could have a good time decorating a Christmas tree. It’s something for little kids, he thought. Now he was decorating and listening to the stove humming and crackling in the warm, cozy trapeza. Wonderful, delicious smells were coming from the kitchen, and snow-white trees stood in the frost outside the windows covered in an icy pattern. Snowflakes softly swirled.

In the evening, Fr. Savvaty called Misha and Peter to his cell. These were the best moments. There was such a wonderful smell in Batiushka’s cell—Athonite incense, icons, books. And Fr. Savvaty would start to talk about Mt. Athos, about the mountain trails, about the monasteries of Mt. Athos.

When they left the abbot’s cell, the blue night had already descended upon the monastery. Huge stars shimmered in the sky. A light was burning in the cave of the manger scene, and the light of its holy inhabitants illumined the path to the cells.

They stopped for a moment at the snowy cave. As they stood there, Misha suddenly felt an unusual fullness of life, impossible to convey in words. He couldn’t. When Peter asked: “Mish, why are you so silent?” he only quietly said:

“You know, Peter… It’s so good to be living in this world!”

He was worried his friend wouldn’t understand and would laugh and scare away the mood. But Peter understood and replied seriously:

“Yes, brother Misha, it’s good… ‘I see, I hear, content. I know it all.’ That’s Bunin, brother…”2

The Nativity was approaching. They were expecting frost, and after trapeza, all the younger brothers hauled firewood on sleds from the woodshed to the cells and the trapeza, so on Nativity itself they could celebrate the feast and relax without worrying about firewood. Everyone was in felt boots, padded jackets, and hats with earflaps. They worked efficiently.

Returning with a sled full of firewood, Peter and Misha froze before they could reach their cell: Misha’s parents were rushing to meet them. They looked concerned. They passed by them, only nodding their heads in greeting.

Misha was confused: His parents didn’t even notice him. They went up to the woodshed, passing by all the working monks and hurried back. They returned to the frozen Misha and Peter and stopped next to them. Misha’s mother asked plaintively:

“Fathers, have you seen our Misha, our son?”

His father nodded his head in agreement. Misha and Peter looked at each other in amazement, and his mother wailed even more mournfully:

“What’s going on?! Dear fathers! Have you seen our son Misha or not?”

Then Misha finally regained the power of speech. He sheepishly uttered in a deep voice:

“Come on, Mom. It’s me, Misha.”

Peter looked at his friend carefully: a sweatshirt, boots, and an earflap hat down to his eyebrows. But it wasn’t his clothes that made him unrecognizable. Instead of the pale, dim-eyed boy who had arrived at the monastery a few months ago, there stood a ruddy, fat-cheeked Misha with a lively and joyful look.

That’s their Christmas story.

“I didn’t sleep a wink”

Some guests came to the monastery for Nativity. The guest house was crowded, and one of the guests, Volodya, was blessed to stay in the cell of Fr. Valerian, whom he had come to visit. They put out a cot for him.

Before going to bed, Fr. Valerian warned his guest:

“Sometimes I snore in my sleep. Just give me a shove if I do.”

And that settled that. Night came. Fr. Valerian immediately began snoring loudly. Volodya hadn’t managed to fall asleep, and now he wouldn’t be able to. He whistled, and Fr. Valerian stopped snoring. It worked!—Volodya rejoiced. But after about fifteen minutes, it all happened again. And again… and again…

In the morning, Volodya, who hadn’t slept enough, decided to jokingly express his dissatisfaction:

“Someone snored so hard all night that I couldn’t sleep!”

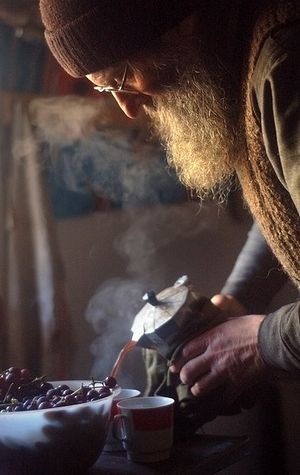

Photo: Alexander Kuzmin / Photopolygon.com

Photo: Alexander Kuzmin / Photopolygon.com

Sleepy Fr. Valerian answered him:

“I didn’t sleep a wink: Someone was whistling all night!”

Firewood for Fr. Theodore

Photo: Alexander Kuzmin / Photopolygon.com The old schemamonk Fr. Theodore was short, thin, but very no-nonsense. Despite his age, he often gave the monastery brethren a hard time.

Photo: Alexander Kuzmin / Photopolygon.com The old schemamonk Fr. Theodore was short, thin, but very no-nonsense. Despite his age, he often gave the monastery brethren a hard time.

“There’s no order in the monastery! Is that how they shovel snow?!”

He would snatch the shovel from the hand of some monk and start to do it himself—and he did such a good job! Everyone knew Fr. Theodore, and they loved him—he meant no harm. Once the young Hieromonk Simeon decided to secretly help the old man.

Fr. Theodore was almost out of firewood, and he had to go pretty far to get more. Knowing the schemamonk’s scrupulosity in all things, Fr. Simeon secretly brought the lightest firewood on a sled that night, cut in uniform pieces. Having replenished the woodpile to the top, he headed for his cell with a feeling of joy for the work he had done.

In the morning, everyone was deafened by the shout of Fr. Theodore. Looking out of their cells, the brothers beheld the woodpile lying in the street, the remaining beautifully-selected firewood flying out of the corridor.

“Who brought this wood?! They blocked everything! And the old man has to move it! What a genius! It’s not birch; it’s all aspen! It’s not firewood, but I don’t know what it is! There’s no order in the monastery!” Fr. Theodore shouted.

If you’re thinking that Fr. Simeon was offended, then listen to the rest of the story: The next morning, the brethren were woken by the old schemamonk’s loud cry:

“See, birch wood, that’s what I need! They finally figured it out! They finally got it through their thick skulls! You have to do things right the first time! You teach these young people order, you teach—and all for nothing! There’s no order in the monastery!”

The brothers shook their heads, and only Abbot Savvaty and Archimandrite Zachariah smiled to themselves. They well remembered the monastic rule: “He who reproaches us gives us a gift. But he who praises us, steals from us.”

They also knew that, after having his shout, Fr. Theodore would close the door to his cell and immediately calm down as if he had never seemed angry. He would calm down, quietly get down on his old frail knees, and pray for his benefactor and all the monastery brethren for a long time.

“Who was this beautiful work made for?”

One time, around Christmas, Fr. Theodore got very sick. He was almost ninety, and his whole life was spent in labors! The brethren were upset, but monks try to always preserve the remembrance of death, and they ordered a coffin and cross for Fr. Theodore.

Hieromonk Simeon took the Holy Gifts and went to commune the patient. Fr. Theodore lay motionless on his bed, his eyes rolled back in his head—everything indicated the approaching mystery of death. Fr. Simeon gave Unction to the dying Fr. Theodore and communed him with a drop of the Blood of Christ.

The next day, during the festive Nativity meal, the door to the trapeza swung open with a bang. On the threshold stood the very-much-alive Fr. Theodore! Not a trace of the previous day’s mortal infirmity remained!

On the way to the trapeza he noticed the new coffin that was drying in the winter sun. It was beautifully made: The monastery worker Peter of the “golden hands,” had come up with the carving design—it was for Fr. Theodore after all! Fr. Theodore liked the carving very much.

“Who was this beautiful work for?” he loudly asked the brothers as he walked in.

How Fr. Theodore prepared for trapeza

Photo: Alexander Kuzmin / Photopolygon.com Fr. Theodore suffered two heart attacks, but was still quite energetic for his ninety years of age. Only, he couldn’t chew hard stuff anymore. And so as not to spoil his bread by taking off the crust, he always went to trapeza early.

Photo: Alexander Kuzmin / Photopolygon.com Fr. Theodore suffered two heart attacks, but was still quite energetic for his ninety years of age. Only, he couldn’t chew hard stuff anymore. And so as not to spoil his bread by taking off the crust, he always went to trapeza early.

And today, Dionysiy hadn’t even gone around the monastery ringing the bell and Fr. Theodore was already sitting demurely in his place, preparing for the meal. It was the week of the Nativity, the brethren were joyful, and Fr. Theodore was also in high spirits. He was crumbling bread crusts into his soup, smiling happily, looking at the Christmas tree, trimmed and standing in the corner of the trapeza.

Fr. Valerian casually looked into the trapeza, and seeing Fr. Theodore, cheerfully asked:

“What, Father, are you soaking your crusts?”

Fr. Theodore nodded his head happily.