Recently reposed Archimandrite Antony (Guliashvili) talks about eldership, punishment, his spiritual father, Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), and why Russia and Georgia are inseparable.

Why are there no elders today? Because there are no disciples

To really help your spiritual child, you yourself have to be well prepared. And now, what can you really ask of a young priest in most cases? A ninety-year-old grandmother confesses to him, and he doesn’t even know about the existence of the kind of sin she confessed to him. I feel sorry for these young people; very sorry.

Why are there no elders today? Because there are no disciples. When we were novices, we had elders. We tried to emulate our spiritual guides, observing how they moved, talked, gave instructions, etc.

I said to Batiushka John once, “Fr. John, I want to ask you—time passes inexorably, as you yourself say. One day is consumed by the next, and everyone is moving towards their end—what will we do without you? You’re our elder!” And he replied: “I’m not an elder—I’m old. But if you want, call me a good old man.”

And now a priest is just beginning to grow a beard and he already calls himself a young elder. What’s the use? I know one young man who was very, very good at first. At least that’s how he acted. But as soon as he started getting some encouragement, he stopped greeting people. What kind of elder is that? I spoke with him recently and I said, “Child, neither I nor the older generation really need your greeting, but do you understand that this behavior of yours will gradually have pride and arrogance creeping up in you? It’s called prelest,1 and it will be very, very difficult to get rid of it.”

—You said that St. Ephraim the Syrian’s Spiritual Psalter says that he who loves his student punishes him. But in society today, especially among cultured intellectuals, they often argue about whether or not you can physically punish your children—spanking them, for example. More and more, intellectuals say you can’t even lay a finger on a child. What do you think of this view?

—I have a negative view of spanking children.

—But you yourself talk about punishment.

—Punishment shouldn’t consist of spanking. If you spank a child, when he grows up, he’ll think that if you want to punish someone, you have to beat him, or even kill him. I don’t reject strictness, but it has its limits. You have to show a child that their behavior is bad by your own example. Children have to be educated, not trained. You train animals and cattle.

Such a child won’t grow up Orthodox

—People debate now about when people were more moral—in the Soviet era or now?

—In the Soviet era.

—Why do you say that?

—In the Soviet era, when we came home from school, one child would go to swimming lessons, for example, and another to make model airplanes. I would play soccer or something else in the yard. But it was enough to hear the bell ring and I would go to church. No one could tear me away from the Church or stop me.

—Were you a Pioneer and Komsomolets?2

—I was never a Komsomolets. I was a Pioneer, but I didn’t wear the signature tie. When I left school, I would always take off the tie and hide it in my bag. As I got close to home, I would put it on again, because my mother was against the Church then. It was the same thing in the morning when I left. I would put the tie on at home, and as soon as I got around the corner, I put it in my bag again, and I would put it back on closer to school. That’s the kind of Pioneer I was.

—Do people really not strive for the Church this way now?

—I’ll tell you from the examples I see of how parents lead their children to church.

The parents are standing in church, and the children spend the whole time playing in the yard. As soon as Communion starts, mama goes out and drags the child into church: “Let’s go, Batiushka’s going to give you some medicine now.” Such a child won’t grow up Orthodox. You have to tell them from the very beginning, as soon as they begin to learn to go to church, what it is that Batiushka is giving on the spoon. If you tell the child that it’s medicine or just sweet wine, then when he grows up, he won’t find it interesting or necessary.

For example, when friends or relatives bring a child to me, I ask him, “Do you want to be good and handsome, to be good at soccer and dancing, to sing and study well?” Of course he says yes. So I say, “Then you have to always live together with God. And what is God? God is what you go to church and receive in Communion, receiving into yourself His Body and Blood, which He has given to us men.”

If you give a child this kind of correct formation, then even if he grows up to be someone, even the secretary of the district committee, he’ll still be a good person. But what does God need? That we would be good people, or just believers?

—Probably both. But the secretary of the district committee can’t be a believer?

—I lived in those times and I can say that many district committee secretaries were secret believers. Many would come to me and say: “Fr. Antony, what can I do to atone at least a little bit for my guilt before God?” I would tell them: “Try this first. You have some document on your desk—some kind of petition or request. And you know that it’s a fair request, but something doesn’t allow you to help this person. But take it and overcome yourself, and do what they’re asking.” And many people, even district committee secretaries, did what I said. After all, it is said, Not every one that saith unto Me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the Kingdom of Heaven; but he that doeth. the will of My Father Which is in Heaven.

—But still, Fr. Antony, why do you think people were better in Soviet times?

—Maybe I’m mistaken, but there was less bad information and bad news all around then. It was good for us. What’s the point, for example, of spreading information that a family of cannibals has been discovered? After all, both believers and unbelievers, fallen and good people hear it. A good person takes this news with sorrow, but a fallen person might think about doing the same thing.

—Were there fewer temptations?

—There were fewer temptations, and more strictness. And families used to have more joy and unity. Today it’s usually every man for himself. The husband has his business and the wife hers. They don’t make up a single whole, and so divorces have become more frequent.

—Perhaps the reason for the latter is modern technology—computers? Today, you often have one person behind one computer in the evening and another behind another. People used to at least be united around the TV.

—Fr. John (Krestiankin) had a good answer about this. If all this exists, it means the Lord allowed it to be so. That’s unambiguous. But He also allowed man to be the crown of all creation. He should put his mind in motion. If the computer bothers you, turn it off. Otherwise, you aren’t in control of yourself. There is no sin the devil can force you to do if you yourself don’t want to.

People used to go visit one another, speak with one another, now they only talk on the phone. Now people are just wrapped up in themselves. He comes home from work, eats, lays down, watches TV, and goes to sleep. In the morning, he gets up and does it all over again.

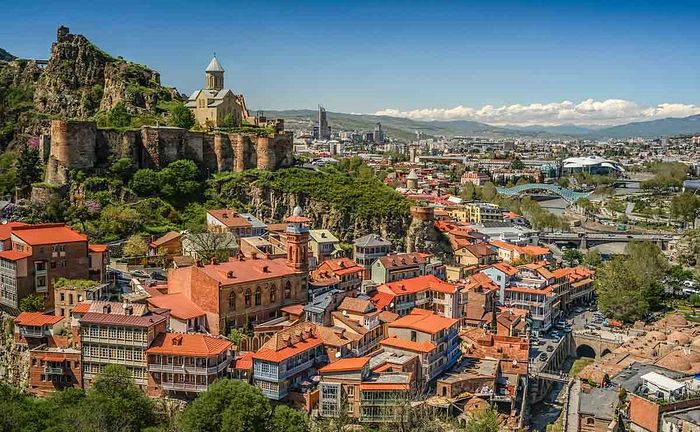

Russia and Georgia

—Fr. Antony, how, in your view, does Georgia differ from Russia today? For example, in terms of morals?

—Almost not at all. But we still try to stick to the old traditions.

I share the opinion of the older generation, for whom all events were held at home. There’s the example of the words of one elderly woman: “Why don’t you want to have the wake in a restaurant? It’ll be easier for you and you won’t have a hassle at home.” But she answered, “My son was born here, he grew up here, and the last piece of bread in honor of his memory should be eaten here.”

They seem to be backwards traditions, but they are still alive for us. And they’re good traditions. That’s how my grandmother’s children grew up. And no matter what happens, I can’t imagine a guest coming to visit me and me taking him to a restaurant. I should receive a guest into my house, and whatever I have, I should share with him.

Most Georgians are favorable towards Russia today

—I don’t want to get into politics, but I can’t help but ask about current relations between Russia and Georgia. Do you think the present situation of, if not enmity, then a very strong difference between them, will last a long time? Maybe even forever?

—No!

—Why don’t you think so?

—I’ll give you the example that I used to start my book, A Day in the Life of a Priest, and Other Stories. If you can ever imagine the Eucharist separately—the Body of the Lord separate and the Blood separate—then I could agree that Russia can live without Georgia, and Georgia without Russia. But it is impossible to divide the Eucharist. If Russia is the grain in the loaves, then Georgia is the wine.

—But, Fr. Antony, on the other hand, relations between Russia and Georgia are still interpersonal, worldly relations, and everything in this world is transitory, and sooner or later it all ends.

—I agree with you, and I’ll answer as an Orthodox priest, in the words of one of our Georgian historians and thinkers Plato Ioseliani: “Times pass, people and events change, but the Church of God is indestructible and eternal.”

Most Georgians are still favorable towards Russia today. I assure you. Today, Russians love to go on pilgrimage and excursion to Georgia, which has always been renowned for its hospitality and cordiality. And our guests from Russia feel this warmth when they come to visit us in how we greet them and how we treat them.

I was asked once, “Are you really so rich that you can welcome guests from Russian like this?” And I said, “Haven’t you ever thought about the fact that we have a family budget too, and every head of the household allocates his budget for the whole month? Now imagine this picture: I’m awaiting a dear guest from Russia, and I tell my wife that we have to reduce our monthly budget because a guest is coming soon, and we should receive him properly. Maybe today we set such a luxurious table for our guest that he is amazed, but then we cut our budget for the rest of the month.” This kind of hospitality is in the blood of Georgians, and those who come visit us understand it well.

—You were a spiritual child of Fr. John (Krestiankin) for forty years. How did this work? Did you to go to the Pskov Caves Monastery regularly?

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) with Archimandrite Antony

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) with Archimandrite Antony

—Yes, two or three times a year—because there was no visa regime then, and we could go at any time. One time when I arrived, the brothers started to murmur: “Oh, he’s here again, and now no one will get to see Batiushka until he leaves.” When word of this reached Fr. John, he called them and others and said, “You see, my children, he comes but once a year, but you are here every day.”

He was the incarnation of love. When I would come, he would always ask me about my mother. He knew she was against my priesthood and monasticism. Then once, ten years before her repose, he greeted me with this same question at first, but then suddenly said, “She won’t die until she receives the tonsure.” And five days before her death, my mother was indeed tonsured.

So when people ask me today, “Fr. Antony, what do you think, will Fr. John be glorified among the saints?” I don’t care at all. Not at all. For me, it’s absolutely clear that he’s a saint. Fr. John has worked so many miracles for me during his life and after death…

—What miracles?

—First, without knowing my mother, he called her by name. My mother and I first went to the monastery together on the forty-day memorial of Vladyka Theodore. Dormition Square was full of people and no one was being let into the caves. And we were standing there among the people—mama, my assistant, and me—but without any hope. They were all Russians—their own people—so who would let us in? No one knew us.

—Wasn’t your mother Russian?

—My mother was Ukrainian, from Krasnodar. Her maiden name was Zagorulko. So, we were standing there among all the people, when suddenly there was some kind of noise. Everyone was making way, forming a corridor. Fr. John was coming. He had his cell attendant, Vanya, with him, who is now Archimandrite Philaret. So, Fr. John was walking past us when he suddenly took my mother by the hand and said, “Theodosia, come with me.” Mama later told me that her knees buckled—he’d never seen her before, but called her by name.

There was also the time I just told you about, when he said, “She won’t die until she becomes a nun.” And there are many, many other instances when Batiushka’s words came true. I believe he showed his holiness with his whole life.