Little Olga with St. John of Shanghai

Little Olga with St. John of Shanghai

The first meeting with St. John of Shanghai’s spiritual children

My first meeting with spiritual children of St. John of Shanghai was in 2015. It was then that I met Margarita Dubrovskaya (Baroness Rida von Luelsdorf) and Maria Potapova, the wife of Archpriest Victor Potapov, Dean of St. John the Baptist’s Cathedral in Washington D.C.

What’s surprising is that I hadn’t sought to meet the saint’s spiritual children—I had no idea that this acquaintance would take place and that they would share with me their most personal memories of this great saint of the twentieth century.

“The Bitter Herb of Exile”

Rida’s story inspired me to write the book, The Bitter Herb of Exile, which I dedicated to St. John of Shanghai. Since its publication, I have met a dozen people who remembered him well and began to share their memories of him with me. These were archpriests who knew St. John of Shanghai personally or took part in the opening of his relics, his assistants and acolytes who travelled with him from Shanghai to the tropical island of Tubabao and then on to faraway San Francisco.

At St. John of Shanghai’s relics

At St. John of Shanghai’s relics

On how I lost the sense of time and space

It was a miracle that I was able to venerate St. John’s relics at his Holy Virgin Cathedral in San Francisco, built in honor of the “Joy of All Who Sorrow” icon of the Mother of God. We also visited the so-called “Old” Cathedral (where Vladyka had served while the New Cathedral was under construction) and met its dean, Hieromonk (now bishop) James (Corazza). He turned out to be a very cordial and considerate pastor, and though the evening service was over and all the parishioners had left, and in spite of his noticeable fatigue, he celebrated a moleben especially for me and two of my companions, during which he covered me with the saint’s mantle.

I knelt through the entire service by the analogion (lectern) with St. John’s icon, covered with his mantle, losing the sense of time and space, as if I were in heaven and not on earth. St. John showed me such an undeserved grace. Fr. James showed us around St. Tikhon’s Orphanage with its dining room, chapel and Vladyka’s cell and even allowed us to sit in the saint’s armchair.

In St. John’s cell at St. Tikhon’s Orphanage in San Francisco

In St. John’s cell at St. Tikhon’s Orphanage in San Francisco

A new person who knew the saint well

Several years passed, and I thought that all the wonderful discoveries had finished. But quite recently, and completely unexpectedly, a new person who knew St. John well appeared in my life.

This person is Olga Vladimirovna Hawkes, nee Rossi. Interestingly, her maiden name is Italian. Her father was Vladimir Emilievich Rossi, and her mother, Sofia Lvovna, bore the German surname Balk before getting married. One of her grandmothers had the surname Rousseau.

In addition to Russians, Olga’s ancestors included Germans, Italians and Frenchmen. They had come to the distant, northern land of Russia under Tsar Peter I when German craftsmen, Italian architects and French tutors considered it an honor to work for the Russians. They married Russian women, had many children and became Russified. Centuries passed, Russia became the motherland for the Rossis and the Balks, and only the foreign surnames testified that their ancestors had once lived in other countries.

“I talk to St. John of Shanghai as if he were alive”

Olga Vladimirovna didn’t merely know St. John—it was he who chose her name when she had just been born, and who performed the funeral of her beloved father several years later and blessed her long and happy marriage. Olga grew up in San Francisco with other children from the orphanage, where they had been brought by St. John from Tubabao. He brought up a whole generation of Russian children, and the spirit of Vladyka was among them.

Olga says of herself:

“I pray to St. John of Shanghai, wonderworker of San Francisco, day and night. I talk to him as if he were alive.”

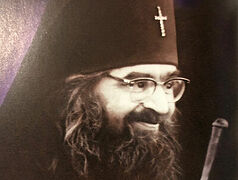

Vladyka John of Shanghai with his assistants

Vladyka John of Shanghai with his assistants

St. John of Shanghai

In 1942, Shanghai was occupied by the Japanese. It was a tough time for everyone who had found shelter in the huge cosmopolitan city. One Russian family, Vladimir Emilievich Rossi, a former White officer, and his wife, Sofia Lvovna, were raising their first child, Marina, and were expecting a second.

Sofia Lvovna, known as Sonechka within the family, was a sweet, kind and very religious woman. She would often visit the orphanage in Shanghai founded by St. John.

Vladyka John had come to Shanghai in 1934 when around 50,000 Russians were living there. He became their father and intercessor, a man of prayer and support. Under St. John, the Cathedral of the “Surety of Sinners” Icon of the Mother of God was built there. With his blessing and participation, a hospital, classical school (gymnasium), nursing homes, a public dining hall, and a college were constructed as well.

Vladyka also established a home for orphans and the children of poor parents in honor of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk. At first there were eight children at the orphanage, but later there were dozens and even hundreds of them, and over the years of its existence it became home to 3,500 children. Vladyka himself picked up sick and hungry children from the Shanghai slums.

Sonechka often helped St. John at the orphanage and he knew her well. Sofia Lvovna and other kind-hearted Russian assistants like her were nicknamed “lady patronesses” of the orphanage.

Archbishop John on his arrival in Shanghai in November 1932

Archbishop John on his arrival in Shanghai in November 1932

The girl that St. John of Shanghai named

Sonechka went into labor on time and Vladimir Rossi, agitated, took her to the hospital. It was nearly morning when he returned home, but did so as a happy father of two girls. He met Vladyka John, whom he knew well, on his way home. It is well known that he never slept in a bed, but only occasionally dozed off while sitting in a chair. He spent nights visiting the sick, praying for the dying and saving orphaned children from imminent death. Numerous cases of healing of hopeless patients through his prayers were known even then.

That night, as Vladimir was walking home from the hospital, Vladyka was heading to visit some sick people. The happy father hadn’t yet had time to share his news with anyone and was shocked when St. John said to him, “Congratulations, Vladimir Emilievich! What are you going to name your daughter?”

Not only did he know that Sonechka had given birth to a baby—he already knew that it was a girl! Confused, Vladimir could only answer, “We haven’t decided yet.”

Vladyka said with a smile, “You are Vladimir. Therefore, your daughter should be Olga.”

And the baby was baptized with this very name.

Archbishop John with parishioners

Archbishop John with parishioners

Vladimir Rossi and his parents

Vladimir Emilievich Rossi, Olga’s father, was no longer young when his second daughter was born—he was forty-eight, and had already passed through the terrible First World War and even more terrible Civil War. Vladimir was born on July 26, 1894 in St. Petersburg, and his parents were famous and respected people in the capital of the Russian Empire. His Father, Emil Karlovich Rossi, graduated from the Imperial Military Medical Academy, fought in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and worked as the chief physician of a military hospital. For many years, he raised five nieces orphaned after his sister’s death and saw all five of them get married.

As Emil Karlovich devoted so much time and energy to his service as a doctor, it is no surprise that he started his family late—he was over fifty when he married his young chosen one, the twenty-three-year-old Sofia Fedorovna. He retired with the rank of privy councilor; in the army, this civil rank corresponded to general. The Rossi family had two children: Vladimir and Dora (Dorothea), who was four years older than her brother.

When Sofia Feodorovna was expecting a second time, Emil Karlovich asked His Majesty Emperor Alexander III to honor him by becoming the godfather of his future child. The Emperor graciously agreed. Unfortunately, he suddenly passed away on November 1, 1894, at the age of forty-nine. When Crown Prince Nicholas II ascended the throne, he learned about his father’s promise and sent Sofia Fedorovna a brooch from Faberge and an elegant ladies’ watch-pendant.

Grandfather Emil Karlovich Rossi

Grandfather Emil Karlovich Rossi

The Page Corps

Emil Karlovich Rossi died in 1913, just as his nineteen-year-old son Vladimir was set to graduate from the Page Corps, an elite imperial military school housed in the Vorontsov Palace in St. Petersburg. Only the sons or grandchildren of the highest ranks of the army or officers who had died in battle were admitted to the Page Corps, and its students were under the personal patronage of the Emperor.

During their studies, the young men were considered to be attached to the imperial court and systematically carried out guard duties. It was considered a great honor and privilege for a page to be elevated to the rank of chamber-page; only the best of the best students could hope to do so—those who excelled in their studies and behavior, and also spoke foreign languages fluently. Vladimir Rossi was elevated to the rank of chamber-page and was proud of this honor.

During the celebration of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov Dynasty, in February and March of 1913, the young cornet Vladimir Rossi was the chamber-page of the sixteen-year-old Grand Duchess Tatiana, the second daughter of Tsar Nicholas II. Vladimir accompanied the Grand Duchess at several important state events and balls and even had the honor of dancing with her.

Later he joked that those dance lessons, so unloved in the Page Corps, came in handy. Then it was impossible to imagine that just five years later Grand Duchess Tatiana, charming and full of life at the age of twenty-one, would be brutally murdered along with the entire Royal Family in Ekaterinburg.

A young cornet in the First World War

After graduating from the Page Corps, Vladimir Rossi joined the Russian Imperial Guard, as a cornet in the Horse Grenadier Regiment. The brilliant Guard had always been a stronghold of the Throne and the Fatherland—they were the first to die on the bloody battlefields of the First World War.

The loyal guardsmen had to show an example of courage and fortitude to other regiments, and they showed it, fearlessly dying under German shells on the most dangerous sectors of the front. Horse Grenadiers were thrown into the attack against the German machine guns, and the fearless horsemen were mown down along with their clever horses.

During the offensive near Kovel in the summer of 1916, the flower of the Russian troops, the Imperial Guard, was thrown into the attack with almost no artillery reinforcements (there were not enough shells) under powerful enemy fire and along the swampy floodplain of the Stokhod River, a difficult obstacle. The boggy ground became a mass grave for half of the imperial guard—fifty percent of the lower ranks and eighty percent of the officers died there.

The young Cornet Vladimir Rossi miraculously survived and was awarded the Orders of St. Stanislav and St. Anna “For Bravery.”

On the eve of the War. At the bottom, “Papa” written by Olga’s hand with an arrow pointing to Vladimir Rossi

On the eve of the War. At the bottom, “Papa” written by Olga’s hand with an arrow pointing to Vladimir Rossi

In the Volunteer Army

After the Revolution, Vladimir fought in the Volunteer Army under Denikin’s command, together with the Don Cossacks, who loved him very much. At twenty-four he was made a colonel.

In one of the last battles near Perekop, the young colonel was seriously wounded, carried away from the battlefield by the Cossacks, taken aboard a steamer and evacuated from the Crimea in an unconscious state. He came to his senses in Constantinople.

His mother died of typhus in Novorossiysk in March 1920. His older sister Dora left Russia immediately after the Revolution—no one else was waiting for Vladimir in his homeland.

Life in foreign lands

Thus began his life in foreign lands: Constantinople, Italy, France. Vladimir drove a taxi in Paris, worked as an editor for a Russian newspaper and as a guide for wealthy Americans.

When the Great Depression interrupted the flow of tourists from America, a former classmate from the Page Corps invited Vladimir to Shanghai, and promised to help him get a job in the municipal police department of the French concession where he worked. His knowledge of several European languages and erudition came in handy: he translated documents and compiled analytical reports.

Marriage

In 1929 in Shanghai, Vladimir Rossi, aged thirty-five, met his future wife, the twenty-four-year-old beauty, Sonechka Balk. They were married in the Church and had two daughters: Marina and, in 1942, Olga. We have come back to the beginning of our story.

Olga Vladimirovna recalls how much she loved her dad, how they would go together to buy rye bread at a Russian bakery, and how she always asked her father to carry her—it was so good and comfortable in his strong, familiar arms.

The young Sonechka Balk, Olga Vladimirovna’s future mother

The young Sonechka Balk, Olga Vladimirovna’s future mother

A troubled year

The year 1947 came. It was a very troubling year. After the Japanese occupation, a civil war broke out. China’s largest city of Shanghai, with a population of six million, became the center of confrontation between the Kuomintang [the Nationalist Party in China founded in 1912.—Trans.] led by Chiang Kai-Shek and the Communists of Mao Zedong.

It was in 1947 that Mao Zedong’s Communists turned to the Soviet Union for help, and Soviet soldiers appeared in China. A curfew was imposed in Shanghai, with propaganda rallies and mass demonstrations, factory owners’ public confessions, demonstrative executions, and terrible inflation. European companies recalled their employees out of China, and Shanghai gradually emptied.

The arrival of the Chinese Communists threatened the Russians in Shanghai with either deportation to the USSR or time in a Chinese prison; the Chinese Communists were very cruel to their ideological opponents. In Shanghai at that time, out of 50,000 Russians about 15,000 remained. About 10,000 of them decided to return to Russia, where they were promised Soviet passports, forgiveness and complete amnesty for their White Guard past—all of them, with a few exceptions, ended up straight in the Stalinist camps.

Vladyka John of Shanghai didn’t bless anyone to go to the Soviet Union, but he prayed even for those who disobeyed him; many of them recalled that they felt the prayer of the saint during the camps, persecution and exile that came after.

Vladimir Rossi openly criticized the Stalinist regime and discouraged Russians from returning to the Soviet Union, and his opinion was heeded. He enjoyed authority among the Russians in Shanghai.

St. John of Shanghai performed the funeral of V. Rossi

In 1947, Vladimir Emilievich contracted typhoid fever and ended up at the hospital. His wife did not leave him. When things got better and the patient began to be prepared to be discharged, she finally decided to leave him for a while and go to her daughters. Sonya was away for only a few hours, but when she returned she was told that her husband was dead.

Vladimir’s fellow patient, also a White officer, whispered to her that her husband had been given some strange “shake” to drink, after which he began to cough, suffocate and died instantly. His body was immediately rolled out of the ward. Olga Vladimirovna, like her mother, believes that her father was poisoned, but what really happened is now impossible to find out.

Vladyka John of Shanghai (who had become an archbishop in 1946) served the funeral service for Vladimir Rossi. The coffin was covered with flowers, and little Olga, without looking away, gazed at her beloved father’s profile and the white chrysanthemums. Since then they have been inextricably linked with her father’s death.