Part 1: Sts. Arilda of Thornbury and Edburga of Winchester

Saint Edfrid of Leominster

Commemorated: October 26 / November 8

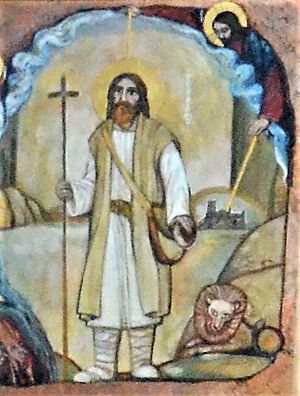

St. Edfrith's painting inside Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (provided by Robert Walker) Herefordshire—one of the greenest, most rural and sparsely populated of English counties—lies near the Welsh border. Numerous hills and rivers, hundreds of orchards, bountiful arable land, tiny villages, isolated communities and distinctive black-and-white half-timbered houses are scattered all over the county. It has many ancient shrines, one of them is the Priory Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in the attractive market town of Leominster1on the River Lugg in the north of the county.

St. Edfrith's painting inside Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (provided by Robert Walker) Herefordshire—one of the greenest, most rural and sparsely populated of English counties—lies near the Welsh border. Numerous hills and rivers, hundreds of orchards, bountiful arable land, tiny villages, isolated communities and distinctive black-and-white half-timbered houses are scattered all over the county. It has many ancient shrines, one of them is the Priory Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in the attractive market town of Leominster1on the River Lugg in the north of the county.

According to a late but picturesque legend, the name consists of two words: “lion” + “minster” in the sense of a monastic church. Legend has it that in the second half of the seventh century, a local king Merewalh of Magonsaete was visited by a priest whom he seated at table for an evening meal. During the dinner a lion appeared as if from nowhere. The priest, unperturbed, took bread and offered it to the predator, which took the treat gently like a lamb.2

The town and its priory church honor the memory of their patron-saint, St. Edfrid (Eadfrith), about whom little is known. He was a Northumbrian monk who in about 660 walked 350 miles to the southwest to preach the Gospel in the kingdom of Hwicce (and in Mercia), which was still largely pagan. In what is now Leominster, this holy priest founded a monastery of St. Peter3 which became famous and was connected with the Royal Family.

It is impossible to say for certain if it was a community for men or women or a double monastery that St. Edfrid founded. Tradition has it that St. Edfrid converted King Merewalh of Magonsaete (a son of the pagan King Penda of Mercia) to the faith and the king took part in the establishment of Leominster Monastery. At that time, Leominster was an island located in a low-lying marshy area. St. Edfrid reposed in about 675 in Leominster, where his memory has been preserved. Almost nothing is known about the fate of his relics—they were not recorded in the inventories taken in the sixteenth century. St. Edfrid was mentioned in the Latin eleventh-century Life of St. Milburgh by the hagiographer Goscelin of Saint-Bertin Abbey (France) and in the eleventh-century Old English Secgan Manuscript (“The Account of God’s Saints Who First Rested in England”).

The monastic community of Leominster suffered at the hands of the Celtic Britons (now called the Welsh) in the eighth century, was plundered by the Vikings in the ninth century and again 100 years later (a hoard, presumably hidden by the Vikings, was found near the town in 2015), and a convent for women appeared soon afterwards that existed roughly until the Norman Conquest. A pre-Norman prayer-book of Leominster written by one of its nuns or abbesses still exists. The convent became so wealthy that in the 1040s, Earl Swein Godwinson abducted its abbess Eadgifu to marry her and take control of the convent’s estates, but had to free her after King Edward the Confessor intervened.

Exterior of Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (provided by Robert Walker)

Exterior of Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (provided by Robert Walker)

In about 1125, a Benedictine Catholic monastery for men, Leominster Priory, was founded by King Henry I together with the more important Reading Abbey (in what is now Berkshire), so Leominster Priory was dependent on Reading. It is uncertain whether it stood on the site of St. Edfrid’s establishment or not, but archeological excavations revealed seventh-century Anglo-Saxon activity on the site of the priory church. Enjoying royal patronage, the monastery could afford construction work on a grand scale (unusually, the church had, and still has, two large parallel naves and a south aisle of a similar size). Leominster and the neighboring area gained prosperity thanks to the trade of local wool, which was of exceptional quality. In 1207, the town of Leominster was burned down by the Welsh, and in 1402, the priory was ransacked again by the Welsh Army,4 but survived. There was likewise much violence in the area during the Wars of the Roses.

In 1539, under Henry VIII, this huge monastery was dissolved, most of its claustral buildings and the church’s east end demolished, the building materials sold, and nearly all the images of the Savior, the Mother of God, saints and angels smashed. But a large part of the former enormous monastery church was spared and has been used as an Anglican parish church ever since. Only the ruins of the Saxon convent of Leominster survive downhill from the priory church. In 1610, a Catholic priest Roger Cadwallader was tried and executed for “treason” in Leominster. In the late seventeenth century, a fire destroyed the rest of the medieval art in the church, with few exceptions. The church interior was thoroughly restored in the nineteenth century by George Gilbert Scott.

Fine carvings on the west door capital of Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (kindly provided by Robert Walker)

Fine carvings on the west door capital of Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (kindly provided by Robert Walker)

Among the church treasures are splendid 900-year-old carvings of men, animals, serpents, birds of prey, vegetation, the “green man,”5 and lions (e.g., a scene of Samson with the lion) on the west doorway capitals by the local Herefordshire school. The church has fine nineteenth-century and older stained glass windows. We mustn’t forget to mention the surviving sixteenth-century missals in Latin, a pre-Reformation paten and silver and gold chalice (the latter kept at Hereford Cathedral), and a rare twelfth-century “wheel of life” wall painting depicting the ten stages of man from birth to death (discovered under whitewash during G. Scott’s restoration) as well. The prior’s house and the reredorter (a latrine for monks) miraculously survived the ravages of Henry VIII’s commissioners.

Splendid carvings on the west door capital of Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (kindly provided by Robert Walker)

Splendid carvings on the west door capital of Leominster Priory, Herefordshire (kindly provided by Robert Walker)

Leominster Priory commemorates St. Edfrid with a special evening service and a lecture of a learned historian annually on his feast-day (October 26 according to the old calendar). On the left of the communion table of the Norman nave’s east end is a painting depicting St. Edfrid. Until recently there was a Greek Orthodox community of Sts. Stephen and Thecla in Leominster, which gathered for worship in the town’s Forbury Chapel.

Another early saint was associated with Leominster—the obscure St. Cuthfleda the Virgin, a princess who became abbess of Leominster after it had been refounded and endowed. Prof. John Blair suggests that St. Cuthfleda’s convent might have been in Lyminster, now in West Sussex, which too had an early minster church. Both Leominster and Lyminster were spelled as “Lemenistre” at one time, but Leominster is far more likely.

There were also more obscure and otherwise unknown Sts. Hemme (Haemma) and Ethelmod of Leominster, who purportedly lived in the late seventh century and are mentioned in a medieval list of the priory’s relics. In the Middle Ages, Leominster Priory received crowds of pilgrims, especially on St. Edfrid’s feast and the major Church festivals. The main object of their veneration was a piece of the Holy and Life-Giving Cross.

St. Edfrid of Leominster should not be confused with his more famous namesake: St. Edfrith († 721; feast: June 4), Bishop of Lindisfarne in Northumbria, who illuminated the Lindisfarne Gospels in honor of St. Cuthbert.

Saint Werstan of Malvern

A view of Great Malvern Priory from the Malvern Hills, Worcs (photo by Irina Lapa)

A view of Great Malvern Priory from the Malvern Hills, Worcs (photo by Irina Lapa)

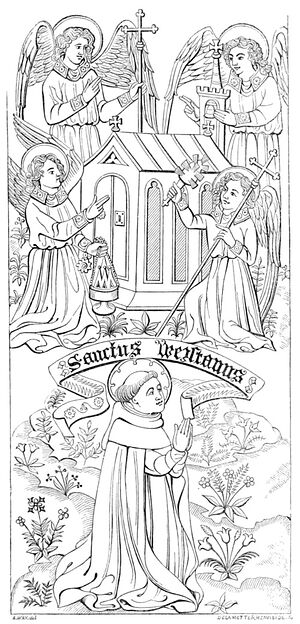

Dedication of the chapel built by St. Werstan (Archaeological Journal, Vol. 2, from Wikisource.org) St. Werstan was one of the last pre-schism saints of the British Isles. Though obscure, he is associated with some of the most important and interesting holy places of western England. No hagiography of St. Werstan survives, though he was mentioned by the antiquary John Leland in the sixteenth century and remembered in local traditions in Worcestershire. According to them, he lived as a monk at Deerhurst Monastery in what is now Gloucestershire in the first half of the eleventh century. It was a time of troubles when the Northmen carried out destructive raids on Britain. After a miraculous vision of the Archangel Michael, St. Werstan left Deerhurst to escape a raid and moved to the picturesque Malvern Hills fourteen miles away, where he first lived as a recluse in a cave and then built himself a hut with a chapel on the slopes above the present-day town of Great Malvern.

Dedication of the chapel built by St. Werstan (Archaeological Journal, Vol. 2, from Wikisource.org) St. Werstan was one of the last pre-schism saints of the British Isles. Though obscure, he is associated with some of the most important and interesting holy places of western England. No hagiography of St. Werstan survives, though he was mentioned by the antiquary John Leland in the sixteenth century and remembered in local traditions in Worcestershire. According to them, he lived as a monk at Deerhurst Monastery in what is now Gloucestershire in the first half of the eleventh century. It was a time of troubles when the Northmen carried out destructive raids on Britain. After a miraculous vision of the Archangel Michael, St. Werstan left Deerhurst to escape a raid and moved to the picturesque Malvern Hills fourteen miles away, where he first lived as a recluse in a cave and then built himself a hut with a chapel on the slopes above the present-day town of Great Malvern.

His chapel was dedicated to the Archangel Michael, or, according to another version, to St. John the Baptist, who was greatly venerated by early anchorites. His hermitage was situated near the ancient St. Ann’s Well (in honor of the Virgin Mary’s mother), where the Victorian Villa of Bello Sguardo was built. After living as a hermit in prayer and solitude, St. Werstan was slain there in his cell by Scandinavians (according to another version, by Welshmen) in the 1050s and was venerated locally as a martyr. The Norman Conquest of England a decade later prevented the wider veneration of this saint—one of the last holy witnesses for Christ in the Old English Church. A small monastery may have been founded in the valley where St. Werstan lived already in his lifetime, though evidence is lacking and it would have been short-lived.

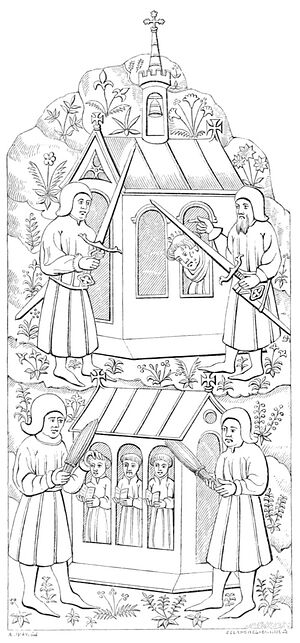

St. Werstan's martyrdom (Archaeological Journal, Vol. 2, from Wikisource.org) At that time, Malvern was a wild and almost uninhabited area. After St. Werstan’s martyrdom, his hermitage was occupied by a succession of hermits, one of them was Aldwyn, who is credited with the foundation of a Catholic Benedictine Monastery known as the Great Malvern Priory in 1085. The monastery was founded with the blessing of Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester (he is venerated by the Catholic Church) and situated below St. Werstan’s cell, at the foot of the Malvern Hills in what is now Great Malvern. It was dedicated to the Mother of God and the Archangel Michael. The first community was small, consisting of thirty monks. At that time, the area was called Malvern Chase—an unenclosed land covered with woods where wild animals were kept for hunting. It was a daughter monastery of the famous Westminster Abbey in London. Despite this, it grew into an important spiritual center. Over the fifteenth century, the priory was substantially expanded to have as many as twelve altars, which accounts for the huge size of the current edifice. One of the most outstanding priors of Great Malvern was Walcher of Lotharingia († 1135), a noted astronomer, mathematician and philosopher who used an astrolabe to measure solar and lunar eclipses.

St. Werstan's martyrdom (Archaeological Journal, Vol. 2, from Wikisource.org) At that time, Malvern was a wild and almost uninhabited area. After St. Werstan’s martyrdom, his hermitage was occupied by a succession of hermits, one of them was Aldwyn, who is credited with the foundation of a Catholic Benedictine Monastery known as the Great Malvern Priory in 1085. The monastery was founded with the blessing of Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester (he is venerated by the Catholic Church) and situated below St. Werstan’s cell, at the foot of the Malvern Hills in what is now Great Malvern. It was dedicated to the Mother of God and the Archangel Michael. The first community was small, consisting of thirty monks. At that time, the area was called Malvern Chase—an unenclosed land covered with woods where wild animals were kept for hunting. It was a daughter monastery of the famous Westminster Abbey in London. Despite this, it grew into an important spiritual center. Over the fifteenth century, the priory was substantially expanded to have as many as twelve altars, which accounts for the huge size of the current edifice. One of the most outstanding priors of Great Malvern was Walcher of Lotharingia († 1135), a noted astronomer, mathematician and philosopher who used an astrolabe to measure solar and lunar eclipses.

During the bloody Reformation under Henry VIII, most of its monastic buildings were destroyed, as were the Lady Chapel and the south transept of the main church. But most of the monastery church was saved by the townspeople who bought it for £20. It has been used as an Anglican parish church called, “the Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Michael” ever since. When the Civil War was raging with the Battle of Worcester nearby,6 the priory church was unscathed as it was still remote and surrounded by forests. In the 1860s, large-scale restoration work was undertaken under the direction of George Gilbert Scott, and the priory’s priceless stained glass was gradually repaired. Anthony C. Deane (1870-1946), a Christian poet and author of religious books, was vicar of Great Malvern between 1909 and 1913.

St. Mary's Priory Church in Deerhurst, Glos (photo by Irina Lapa)

St. Mary's Priory Church in Deerhurst, Glos (photo by Irina Lapa)

Medieval tiles inside Great Malvern Priory, Worcs

Medieval tiles inside Great Malvern Priory, Worcs

Today the priory church is a popular pilgrimage site and tourist attraction. This large twelfth-century church is famous for its huge and fine collection of medieval stained glass, most of which is dedicated to the Mother of God. According to experts, its glass is surpassed only by York Minster. The church is also noted for its medieval floor and wall tiles—more than 1000 of them and over ninety different patterns. The nave is Norman with all its Norman columns still in place. The High Altar has a Victorian mosaic altarpiece depicting the Adoration of the Magi. Another pride of the priory is its set of exceptional fourteenth and fifteenth century carved misericords7 in the chancel which depict mythical creatures, seasonal labors etc. and resemble those in Worcester Cathedral. The large and cozy St. Anne’s Chapel contains many scenes depicting a chronological sequence of events from the Old Testament. The north aisle is used as a bookshop, and the north chapel as a place for quiet prayer.

The nave of Great Malvern Priory, Worcs Apart from medieval glass, there is also Victorian and contemporary stained glass in the church. The west window originally depicting the Last Judgment was donated by Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who in 1483 became King Richard III. It now depicts the Mother of God, angels, saints and bishops. The “Magnificat window” of the coronation of the Theotokos was another royal gift, donated to the monastery by King Henry VII in 1501, though his son Henry VIII spared no object of devotional art in the country, and what remains survived by miracle. There are also two windows, donated for the Golden (1887) and Diamond (1897) Jubilees of Queen Victoria. The chancel is Perpendicular Gothic, as is the central tower (124 ft.) which is similar to that of Gloucester Cathedral as they were built by the same masons. Great Malvern Priory has rich musical traditions and often holds concerts.

The nave of Great Malvern Priory, Worcs Apart from medieval glass, there is also Victorian and contemporary stained glass in the church. The west window originally depicting the Last Judgment was donated by Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who in 1483 became King Richard III. It now depicts the Mother of God, angels, saints and bishops. The “Magnificat window” of the coronation of the Theotokos was another royal gift, donated to the monastery by King Henry VII in 1501, though his son Henry VIII spared no object of devotional art in the country, and what remains survived by miracle. There are also two windows, donated for the Golden (1887) and Diamond (1897) Jubilees of Queen Victoria. The chancel is Perpendicular Gothic, as is the central tower (124 ft.) which is similar to that of Gloucester Cathedral as they were built by the same masons. Great Malvern Priory has rich musical traditions and often holds concerts.

In his guidebook, What to See in Malvern (the eighth edition), John Winsor writes that this great church grows out of the Pre-Cambrian granite on which it is built. Greenish yellow stone from the beds of Cradley, warmed by the pinkish stone of Mathon, were used in its construction. The beauty of this building lies in the fact that the colors change with the season and time of day.

Former gatehouse of Great Malvern Priory, now the Malvern Museum, Worcs

Former gatehouse of Great Malvern Priory, now the Malvern Museum, Worcs

Outside the priory, there is a fifteenth century preaching cross in its churchyard. There are some ancient yews beside the priory. The nearby Priory Park once belonged to the monastery, and the Swan Pool was fed by a healing spring and used as a fishpond by monks. The medieval priory gatehouse now houses the Malvern Museum.

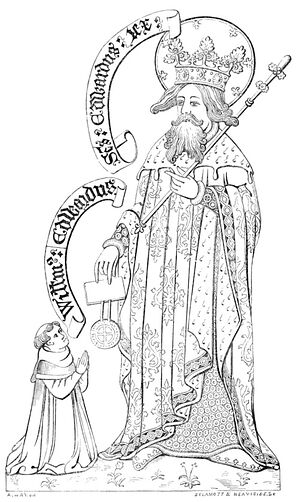

Edward the Confessor is bestowing grant upon St. Werstan (Archaeological Journal, Vol. 2, from Wikisource.org) St. Werstan is immortalized in the Great Malvern Priory Church in a large 1460 clerestory stained glass window in the northern part of the choir which relates the history of this place. It depicts scenes of St. Werstan’s vision, the consecration of his chapel by angels, King Edward the Confessor (ruled 1042–1066) granting his charter for the kneeling saint’s lawful possession of a little plot, and St. Werstan’s martyrdom. Thanks to St. Werstan, monastic prayer and life continued in this idyllic and isolated place for 500 years, and Christian worship goes on to this day. Now St. Werstan is venerated as the patron of the healing springs and wells of Malvern. As for his relics, their whereabouts are unknown. There is a record of their display in the priory in the fifteenth century, while some believe they may lie under the aforementioned Bello Sguardo Villa. His hermitage was preserved for centuries, and when the “Hermitage Cottage,” which had stood on its site, was demolished in about 1830, a church crypt, some carvings, fragments of a coffin and human remains were found under it. A modern award for the enhancement of the Water Heritage of the Malvern Hills is called St. Werstan’s Award.

Edward the Confessor is bestowing grant upon St. Werstan (Archaeological Journal, Vol. 2, from Wikisource.org) St. Werstan is immortalized in the Great Malvern Priory Church in a large 1460 clerestory stained glass window in the northern part of the choir which relates the history of this place. It depicts scenes of St. Werstan’s vision, the consecration of his chapel by angels, King Edward the Confessor (ruled 1042–1066) granting his charter for the kneeling saint’s lawful possession of a little plot, and St. Werstan’s martyrdom. Thanks to St. Werstan, monastic prayer and life continued in this idyllic and isolated place for 500 years, and Christian worship goes on to this day. Now St. Werstan is venerated as the patron of the healing springs and wells of Malvern. As for his relics, their whereabouts are unknown. There is a record of their display in the priory in the fifteenth century, while some believe they may lie under the aforementioned Bello Sguardo Villa. His hermitage was preserved for centuries, and when the “Hermitage Cottage,” which had stood on its site, was demolished in about 1830, a church crypt, some carvings, fragments of a coffin and human remains were found under it. A modern award for the enhancement of the Water Heritage of the Malvern Hills is called St. Werstan’s Award.

The Malvern Hills run north to south for nine miles, stretching along southern Worcestershire, partly in Herefordshire and the northern tip of Gloucestershire. The highest point is the Worcestershire Beacon at about 1400 feet. They offer some of the most beautiful and romantic landscapes, countryside and spectacular views in England. The area is enjoyed by walkers (the walkways crisscross), travelers, pilgrims, poets, writers, artists and musicians. It is said that fifteen counties, the Black Mountains, the Clee Hills, the Cotswolds and the spires of several cathedrals can be seen from the top on a clear day.

The stunning Malvern Hills, Worcs (photo by Irina Lapa)

The stunning Malvern Hills, Worcs (photo by Irina Lapa)

The word “Malvern” is of Welsh origin and means “bare hill.” The rock of the Malvern Hills, mostly the Pre-Cambrian granite, is some of the oldest on the planet, dated by scientists to 600 million years ago, and is from the deepest layers of the earth’s crust. This stone is multicolored and crystalline thanks to numerous minerals. It is very hard—it fissures easily, yet it cannot be carved or be dissolved by rain water, which accounts for the purity of the local springs and wells. The rocks are so ancient that no animals fossils are found in them! South of the British Camp—an Iron Age hillfort amid the Hills—is a man-made cave where hermits used to live.

The major settlements of the Malvern area are called “the seven sisters”: Great Malvern, Little Malvern, Malvern Link, Malvern Wells, North Malvern, South Malvern (or the Wyche) and West Malvern. These scattered parts make up the town of Malvern, with Great Malvern as its center, though in everyday speech Great Malvern is referred to as a “town.” It lies eight miles south-west of Worcester.

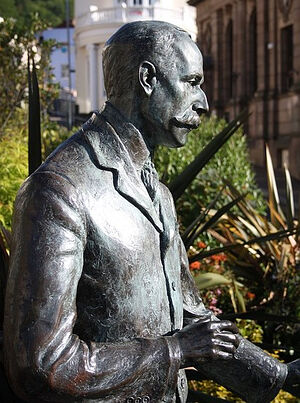

Edward Elgar's sculpture in Great Malvern, Worcestershire The Malverns inspired the medieval author William Langland (c. 1330-c. 1385). His main work is a long allegorical poem in English, “Piers Plowman”, a vision of a Christian pilgrimage partly set in the surroundings of Malvern. The Priory Park in Great Malvern has a bronze bust to Edward Elgar (1857-1934), one of the greatest composers of England—who lived in and around Malvern for many years and used to say that music literally flows in the air there. While in Malvern, he composed (partly or entirely) The Bavarian Highlands, Caractacus8, King Olaf, Sea Pictures, the Black Knight, The Dream of Gerontius, The Enigma Variations, and the Light of Life, among others. Elgar loved the area so much that he said to his friend wistfully shortly before his death in reference to his Cello Concerto, “If ever after I’m dead you hear someone whistling this tune on the Malvern Hills, don’t be alarmed. It’s only me.”

Edward Elgar's sculpture in Great Malvern, Worcestershire The Malverns inspired the medieval author William Langland (c. 1330-c. 1385). His main work is a long allegorical poem in English, “Piers Plowman”, a vision of a Christian pilgrimage partly set in the surroundings of Malvern. The Priory Park in Great Malvern has a bronze bust to Edward Elgar (1857-1934), one of the greatest composers of England—who lived in and around Malvern for many years and used to say that music literally flows in the air there. While in Malvern, he composed (partly or entirely) The Bavarian Highlands, Caractacus8, King Olaf, Sea Pictures, the Black Knight, The Dream of Gerontius, The Enigma Variations, and the Light of Life, among others. Elgar loved the area so much that he said to his friend wistfully shortly before his death in reference to his Cello Concerto, “If ever after I’m dead you hear someone whistling this tune on the Malvern Hills, don’t be alarmed. It’s only me.”

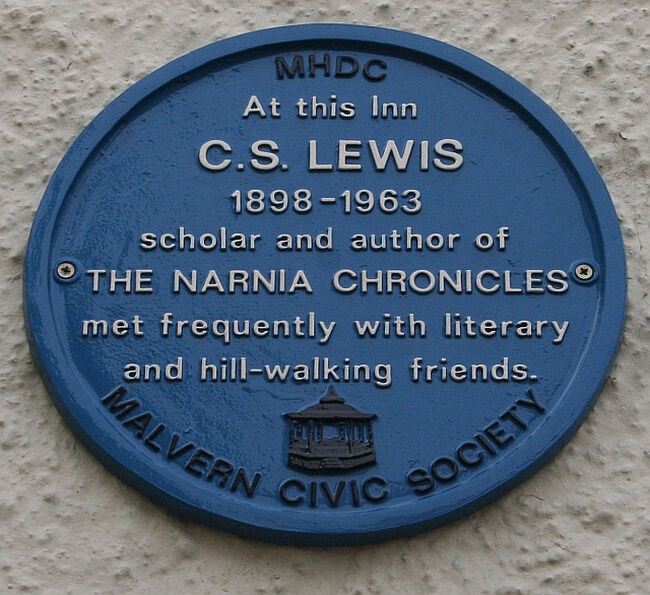

According to some, the Christian author C. S. Lewis derived inspiration in Great Malvern for a detail of his famous Narnia Chronicles. One evening, after visiting a pub in Malvern he was walking along a street when it started to snow, and the light of a gas lamp post began to shine through the snow brightly. (There used to be ninety-three Victorian lamp-posts scattered all over Malvern). Lewis was reputedly so impressed that the lamp-post appeared in Narnia: it was a major landmark in this imaginary land, standing in the middle of the forest and shining day and night. Some believe that the mist-soaked uplands of the Malverns were the prototype for the White Mountains of Gondor in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Plaque dedicated to C. S. Lewis on the Unicorn Inn in Malvern, Worcs (photo by Bob Embleton, Geograph.org.uk)

Plaque dedicated to C. S. Lewis on the Unicorn Inn in Malvern, Worcs (photo by Bob Embleton, Geograph.org.uk)

Among those who visited the Malvern Hills were the painter Edward Burne-Jones, King Edward VII, the conqueror of Everest Edmund Hillary, the seven-year-old future U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and even Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, who went into exile to Britain during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia.

St. Ann's Well in Great Malvern, Worcs (photo by Irina Lapa)

St. Ann's Well in Great Malvern, Worcs (photo by Irina Lapa)

St. Ann’s Well in Malvern may be thousands of years old. It may have been devoted to a pagan deity in antiquity. After St. Werstan’s martyrdom this pure healing spring was renamed St. Werstan’s and subsequently, St. Ann’s Well. It was thoroughly restored in the 2000s. It sits by the Happy Valley and the “ninety-nine steps” footpath that leads up to it from the Belle Vue Terrace in Great Malvern. The spring flows from an elaborately carved spout; there is the famous vegetarian St. Ann’s Well Café a few steps from it. So many miraculous cures were recorded from the fifteenth century that in the early seventeenth century the following song about this holy source was written by Edmund Rea, the Anglican vicar of Great Malvern:

Out of thy famous Hille

There daily springeth

A water passing still

That always bringeth

Great comfort to alle them

That are diseased men

And makes them well again

So Prayse the Lord!

In 1842, Queen Dowager Adelaide (1792-1849), King William IV’s widow, visited St. Ann’s Well. Earlier, in 1831, the twelve-year-old Princess Victoria—the future Queen—made her first public engagement by riding to St. Ann’s Well on a donkey and opening “the Victoria Drive.” Interestingly, she refused to travel without Malvern water.

Hundreds of years ago people also began to visit the Holy Well, the Eye Well (which would heal 113 kinds of eye complaints) and other healing springs of Malvern.9 Many of these springs have curative properties for a lot of diseases. The water is so pure it contains almost no minerals or bacteria, approximating by its purity distilled water, so it is no wonder the British Royal Family are among those who drink it.

The building of the Holy Well in Malvern, Worcestershire

The building of the Holy Well in Malvern, Worcestershire

A few words about the Holy Well, situated in a valley above Malvern Wells. It was visited by pilgrims travelling to Hereford and St. Davids. In ancient times, monks would wrap the sick in cloths soaked in the well water and make them sleep with wet cloths on their ailing body parts. There was the tradition of “dressing” this well on the feast of St. Oswald of Worcester, when those who had been cured in the previous year would come back and give offerings for healing. According to tradition, St. Oswald revealed the medicinal quality of its waters to one hermit in the tenth century. Its water, which is similar in purity to St. Ann’s, has been bottled since 1622. By the eighteenth century, it had become extremely popular. The present well building dates to 1843; it was designed to the pattern of the Baden-Baden spa. The well was restored in 2009. Malvern water is even represented in statuary in the center of Great Malvern. The tradition of “dressing” the springs, wells and spouts was revived in the area some years ago.

The physician John Wall In the nineteenth century, Great Malvern became a famous spa town, known for hydropathy, or water cures—a movement that influenced the whole of Europe. It had begun even earlier, with the physician John Wall (1708–1776), the founder of the Worcester infirmary (which treated scarlet fever and diphtheria) and promoter of Malvern’s development as a spa. He studied the waters of the Malvern wells, improved the facilities and accommodation for patients from England and beyond and initiated the widespread practice of bottling the spring water. The wits of the age put Dr. Wall’s findings into a rhyme:

The physician John Wall In the nineteenth century, Great Malvern became a famous spa town, known for hydropathy, or water cures—a movement that influenced the whole of Europe. It had begun even earlier, with the physician John Wall (1708–1776), the founder of the Worcester infirmary (which treated scarlet fever and diphtheria) and promoter of Malvern’s development as a spa. He studied the waters of the Malvern wells, improved the facilities and accommodation for patients from England and beyond and initiated the widespread practice of bottling the spring water. The wits of the age put Dr. Wall’s findings into a rhyme:

The Malvern water,

Says Doctor John Wall,

Is famed for containing

Nothing at all.

The physician James Gully The first water cure establishment in Malvern was the Crown Hotel. Patients who would come not only from the UK but from as far away as Germany, Russia and the USA, were given care there: a special diet, drinking, dousing, bathing, walks, exercise and other procedures. The most famous doctors who were behind hydrotherapy and contributed to Malvern’s fame as a great spa center were James Wilson and James Gully (1808-1883). The charismatic Gully’s clinic (he later opened two more) had Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens’ wife Catherine, Florence Nightingale, and Alfred Tennyson among its clients. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, hydrotherapy was in decline, and the chief economy of Great Malvern became education, with numerous schools and boarding schools.

The physician James Gully The first water cure establishment in Malvern was the Crown Hotel. Patients who would come not only from the UK but from as far away as Germany, Russia and the USA, were given care there: a special diet, drinking, dousing, bathing, walks, exercise and other procedures. The most famous doctors who were behind hydrotherapy and contributed to Malvern’s fame as a great spa center were James Wilson and James Gully (1808-1883). The charismatic Gully’s clinic (he later opened two more) had Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens’ wife Catherine, Florence Nightingale, and Alfred Tennyson among its clients. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, hydrotherapy was in decline, and the chief economy of Great Malvern became education, with numerous schools and boarding schools.

It was in the Malvern area that the first four-wheeled petrol-engine car in the UK, the “Malvernia,” was produced by the Santler brothers in 1894, and wood-framed sport cars have been produced by Morgan Motors since 1909. Malvern’s famous Winter Gardens Palace has been used as a theater for the annual Drama Festival since 1928, where plays by Bernard Shaw and J. B. Priestley (both were closely associated with this place) along with music by Elgar are regularly performed.

Several years ago, an Orthodox presence finally appeared in Worcestershire. It is the small Antiochian community of St. Anne and All the Saints of Worcestershire, which worships in the village of Bransford on the River Teme near Malvern and makes pilgrimages to St. Ann’s Well.

Great Malvern Priory of St. Mary and St. Michael, Worcestershire

Great Malvern Priory of St. Mary and St. Michael, Worcestershire

Great Malvern Priory was not the only monastery to exist in the Malvern Hills. There was also a smaller Benedictine monastery called Little Malvern Priory, situated in the village of Little Malvern, with its church dedicated at one time to Sts. Mary, Giles and John the Evangelist. It was founded for a dozen monks as a cell of Worcester Monastery-Cathedral and existed from about 1127 until the Dissolution of Monasteries by Henry VIII. The tower and choir of the former monastery church are now used as the Anglican St. Giles Church. Among its gems are a screen with a carved rood-beam, the east window depicting some of the York royalty, medieval floor tiles and a fifteenth-century crucifix. The place is surrounded by the priory ruins and adjoins Little Malvern Court house, which incorporates the former prior’s hall, etc. It is in Little Malvern, on the eastern slopes of the Malvern Hills, that E. Elgar and his wife Alice found their resting place in St. Wulfstan’s Catholic Church.

St. Giles Church in Little Malvern, the medieval priory's remnant, Worcs (by Bob Embleton, Geograph.org.uk)

St. Giles Church in Little Malvern, the medieval priory's remnant, Worcs (by Bob Embleton, Geograph.org.uk)

St. Alphege's Chapel in the Deerhurst Church (copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Church Council) The village of Deerhurst lies close to the town of Tewkesbury. This holy place is unique as it has two Saxon churches: the eighth-century St. Mary the Virgin Priory Church and the mid-eleventh century Odda’s Chapel (in honor of the benefactor Earl Odda) dedicated to the Holy Trinity. It is unknown when the earliest monastery was set up in Deerhurst in the kingdom of the Hwicce. But it flourished in the eighth century and existed for many years, though later it became dependent on St. Denis’ Monastery in Paris. The present St. Mary’s Church, over 1200 years old, was part of this monastery, but has been used as a parish church since the Reformation.

St. Alphege's Chapel in the Deerhurst Church (copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Church Council) The village of Deerhurst lies close to the town of Tewkesbury. This holy place is unique as it has two Saxon churches: the eighth-century St. Mary the Virgin Priory Church and the mid-eleventh century Odda’s Chapel (in honor of the benefactor Earl Odda) dedicated to the Holy Trinity. It is unknown when the earliest monastery was set up in Deerhurst in the kingdom of the Hwicce. But it flourished in the eighth century and existed for many years, though later it became dependent on St. Denis’ Monastery in Paris. The present St. Mary’s Church, over 1200 years old, was part of this monastery, but has been used as a parish church since the Reformation.

In the 970s, the young St. Alphege, the future archbishop of Canterbury and martyr, lived at Deerhurst as a monk but found its discipline too lenient and moved to live as a hermit near Bath. Now St. Alphege is commemorated in Deerhurst church. In 2012, the millennium of his martyrdom, a new altar under the fourteenth-century stained glass window depicting the saint, was dedicated by Dr. Rowan Williams, then Archbishop of Canterbury. An icon depicting St. Alphege was given to the church and placed in the chapel that bears his name. Pilgrims visit the church occasionally.

Carving of the angel on the exterior wall of the ruined apse of Deerhurst church (picture is the copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Council)

Carving of the angel on the exterior wall of the ruined apse of Deerhurst church (picture is the copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Council)

Relief stone sculpture of Madonna at Deerhurst church (copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Church Council) Deerhurst church is one of the most complete surviving Anglo-Saxon churches, which has a lot of unique elaborate carvings and other artworks. Among them are a fine carving of the “Angel of Deerhurst” on an outside wall; the huge carved font with intricate patterns; a heavily faded painting on the east wall depicting a saint holding a book; “monsters’” heads and other grotesques; a double window at the nave’s west end leading to the upper chapel that once housed saints’ relics—all of this is from the ninth or tenth century. A relief sculpture of the Madonna above the nave’s doorway is of the same period. This is how Nick Mayhew Smith describes this in Britain’s Holiest Places: “A lozenge-shaped relief sculpture showing the Blessed Virgin with Christ inside Her womb... It would have been painted, but all color has gone, leaving the merest outlines of a mother’s love. Its geometrical precision is striking in comparison to other rough Saxon pieces. There is nothing similar in early English art, but it has obvious parallels with Orthodox iconography. The composition is known as a Panagia icon. God is contained within humanity: the medallion over Mary’s chest symbolizes Christ in the womb.”

Relief stone sculpture of Madonna at Deerhurst church (copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Church Council) Deerhurst church is one of the most complete surviving Anglo-Saxon churches, which has a lot of unique elaborate carvings and other artworks. Among them are a fine carving of the “Angel of Deerhurst” on an outside wall; the huge carved font with intricate patterns; a heavily faded painting on the east wall depicting a saint holding a book; “monsters’” heads and other grotesques; a double window at the nave’s west end leading to the upper chapel that once housed saints’ relics—all of this is from the ninth or tenth century. A relief sculpture of the Madonna above the nave’s doorway is of the same period. This is how Nick Mayhew Smith describes this in Britain’s Holiest Places: “A lozenge-shaped relief sculpture showing the Blessed Virgin with Christ inside Her womb... It would have been painted, but all color has gone, leaving the merest outlines of a mother’s love. Its geometrical precision is striking in comparison to other rough Saxon pieces. There is nothing similar in early English art, but it has obvious parallels with Orthodox iconography. The composition is known as a Panagia icon. God is contained within humanity: the medallion over Mary’s chest symbolizes Christ in the womb.”

Archeological excavations by the church revealed the remains of a pre-Norman monastery, Saxon burials, a wheel-head cross and evidence of a high-status Roman building. The place must have been of great importance from earliest times. No wonder Kings Edmund Ironside and Canute met near Deerhurst in the early eleventh century to sign their treaty to divide the rule of England.

***

Among the other local saints of western England we should also mention:

-

St. Aldate (+ c. 577; feast: February 4), who may have been a Briton and a bishop in the Gloucester area. He was killed by Anglo-Saxon invaders at Deorham and venerated as a martyr; a modern Anglican church and a minor street in Gloucester bear his name, and an old St. Aldate’s Church stood in the city before the Civil War. In the City of Oxford one of the main central streets is called St. Aldate’s Street and on its west side is St. Aldate’s Church which has Saxon origins but was later rebuilt.

-

St. Cyneburga (Kyneburgh; seventh century; feast: June 25), who according to tradition was the sister of King Osric and the first abbess of Gloucester. Some legends are associated with her. There used to be St. Cyneburga’s Chapel and St. Cyneburga’s Well in Gloucester. Gloucester Museum contains a lead box depicting her with St. Aldate—it once probably housed relics. Several years ago, a life-size statue of St. Cyneburga was unveiled in Gloucester Cathedral and the 52-foot tall “Kyneburgh Tower” was erected as part of a project to connect the city center with the docks and as an art installation.

-

St. Thecla (Tecla; fifth century?) who may have been a Welsh princess and anchoress. She is believed to be the patroness of the parish church and holy well in Llandegla in Denbighshire, Wales. The saint moved to live in seclusion on the isle now called Rock Chapel by the village of Beachley in Gloucestershire beside the Welsh border, where she was martyred by pirates. She lived in extreme conditions—the isle is barren, the currents of the Bristol Channel are violent, and the tidal range is one of the highest in Britain. A chapel in honor of St. Twdrog was erected on the site of her hermitage, which was visited by pilgrims but by the eighteenth century had fallen into ruin. The ruins are still visible.

-

St. Theoc (seventh century) was a hermit in Gloucestershire for whom the picturesque town of Tewkesbury at the confluence of the Avon and the Severn is named. Tewkesbury Abbey of the Virgin Mary was founded in the early eighth century, and the present abbey church began in 1087. Tewkesbury Monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII, but the abbey church was spared and bought by the townsfolk for £453. Now it is used as an Anglican parish church. Tewkesbury Abbey is the second largest church in England and boasts the hugest Norman tower (c. 150 ft.). It has one of the finest collections of splendid stained glass, monuments and artworks. One of its greatest donors was Eleanor de Clare (1292–1337), a powerful Anglo-Welsh noblewoman who was imprisoned in the Tower of London. After her release, she spent most of her fortune on the abbey’s restoration in gratitude to God. Tewkesbury was the scene of a decisive battle (1471) in the Wars of the Roses in which the Yorkists defeated the Lancastrians.

-

St. Weonard (Wannard) was an obscure Welsh hermit (probably a disciple of St. Dyfrig) after whom the village of St. Weonards in Herefordshire and its parish church are named. The church was mentioned in the twelfth century, but the present structure is from the early sixteenth century. It once had a stained glass window depicting the saint as a bearded hermit with a book in one hand and a woodcutter’s axe in the other.

Acknowledgements:

I express sincere gratitude to Mr. Martin Fardell from Oldbury-on-Severn for providing photographs for St. Arilda and the St. Arilda’s hymn; to Dr. Judith Dale from Pershore for providing photographs of windows, a prayer collect and other materials on St. Edburga; to Mr. Robert Walker from Leominster for assisting me in preparation of St. Edfrid’s material and photographs; and to Mrs. Sheila Ryan from Deerhurst for providing photographs of artwork inside Deerhurst church.

The pictures of the angel carving, the Madonna and St. Alphege’s Chapel at the Deerhurst church are the copyright of Deerhurst Parochial Church Council, who kindly gave permission for their use in this article.

Saints Arilda, Edburga, Edfrith, and Werstan, pray to God for us!