As the world celebrated the 200th birthday of Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky, his seventy-five-year-old great-grandson Dmitry Andreyevich spoke to Pravoslavie.ru about their renowned family, his miraculous healing, and love of Staraya Russa.

Dmitry Andreyevich Dostoyevsky with family

Dmitry Andreyevich Dostoyevsky with family

—Dmitry Andreyevich, you belong to a world-famous family. How and where did you celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Dostoyevsky family line?

—I celebrated the anniversary in the bogs of Pinsk on the territory of today’s Belarus. This is where the Dostoyevsky family originated. As I was traveling there by train, I wondered what it would be like once I got there. So, I came, sat down on a stone, and started crying. I was very surprised at myself! I seemingly broke down under the weight of those five hundred years and let the tears flow. Later on, I had a meeting with the director of a local House Museum of Dostoyevsky. It is the only museum of its kind because it is dedicated not only to Feodor Mikhailovich but the rest of the family as well.

—How does your family keep the memory of Feodor Mikhailovich alive?”

—The memory is undying. We have the same genes and we pass down from generation to generation the memory of Feodor Mikhailovich as we inherited nothing else but the genes. Everything else was taken away from the Dostoyevsky family and their descendants in due time, and as my father used to say, in a “volun-datory” fashion. They took everything, pretending we had given it up voluntarily; but it really had nothing to do with our wishes.

—How did you celebrate your anniversary?

—As a descendant of the “bloody, wretched Dostoyevsky”—that’s what Ulyanov-Lenin called the writer—I managed to be born on Lenin’s birthday, on April 22. During Soviet times, flags were flown everywhere on this day. It’s no longer celebrated as a holiday. I thought of inviting close friends and family to celebrate the big day. But before you knew it, COVID was everywhere! We were asked to delay the celebration. That’s why I couldn’t have anything done for my humble seventy-fifth birthday. But we are marking the 200th birthday anniversary of Feodor Mikhailovich at a time of even more severe restrictions—we can only access places like the Dostoyevsky Museum in Saint Petersburg, or the Dostoyevsky memorial house in Staraya Russa, or any other places on condition that we possess a special kind of a code, akin to the ones we see on sales receipts.

About the writer’s descendants

—Tell us about Dostoyevsky’s children.

—Feodor Mikhailovich had four children: both his firstborn and last child died; the only ones who lived were his daughter Liuba and son Feodor. Feodor II (that’s what we call him) continued the family line. He had two sons, Feodor III who died in infancy, and Andrey, my father. My wife and I had only one son Alexey so the male line continues. Alexey gave us three girls, Anya, Vera, and Masha—and grandson Fedya. He is Feodor number four. So, we are good, the lineage continues, and I hope that there will be more Dostoyevskys in the future.

Immediately upon his graduation from engineering school at the age of nineteen, Feodor Mikhailovich declared: “I am not going to work as an engineer, I will be a writer instead.” His son Feodor also quickly realized what he wanted to do—He worked with horses all his life. He became a distinguished equine specialist and published a great number of articles in the Imperial Horse-Breeding Journal. He signed them simply, “F. Dostoyevsky.” Anytime people realized there was a third Feodor, the writer’s grandson who, sadly, died early, they’d start wondering: “Why are there so many Feodors? Feodor Mikhailovich, Feodor Feodorovich?” But there was a tradition in old Rus’ to give the eldest son his father’s name assuming that a large family would have a few more sons. But Feodor Mikhailovich became a father late in life and he couldn’t bear a lot of children. Only two of his four children lived long lives. Truth be told, both of them met a sad demise.

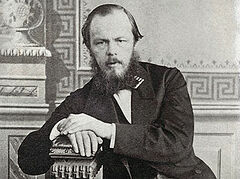

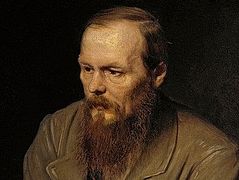

Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky as a young man Dostoyevsky’s daughter Liuba died in 1924 in Italy. She was over sixty years old. A few days before her death, a Czechoslovakian Consul visited her, helping her a great deal. Just recently, we found a letter he wrote at the time: “I must admit that the daughter of the world-famous writer is dying in misery.” His son Feodor died under similar circumstances in Moscow when he was also sixty years old. They both died in poverty because the Bolsheviks “nationalized” the creative legacy of the writer and no one (including his widow) was able to receive book royalties for the publication of his works.

Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky as a young man Dostoyevsky’s daughter Liuba died in 1924 in Italy. She was over sixty years old. A few days before her death, a Czechoslovakian Consul visited her, helping her a great deal. Just recently, we found a letter he wrote at the time: “I must admit that the daughter of the world-famous writer is dying in misery.” His son Feodor died under similar circumstances in Moscow when he was also sixty years old. They both died in poverty because the Bolsheviks “nationalized” the creative legacy of the writer and no one (including his widow) was able to receive book royalties for the publication of his works.

There is some mystery in all of it. I noticed that one’s place of birth plays out mystically in his life. Fedya was born in Petersburg and, as a true Russophile, never exhibited any desire to travel abroad, despite his mother’s pleadings: “Why don’t you go and explore what life is like out there, we have the money!” He retorted: “But I’m perfectly fine here in Russia; I’d rather visit a steam bath!” That’s what is written in those letters displayed at the Pushkin House. Whereas Liuba, who was born in Dresden, took off and left Russia for good, telling her motehr that she was going to stay abroad for a short while to see some doctors. She traveled extensively throughout Europe but suddenly fell ill and died in Alzano in northern Italy. The Italians revered Dostoyevsky’s memory, and the only remains they transferred from a closed, old cemetery to the new one were those of Liubov Dostoyevskaya.

—Didn’t his children attempt to follow in their famous father’s footsteps?

—Liuba declared: “I will be a writer. I will become famous.” But her attempts to become a writer broke her down mentally. When she realized that practically no one reads her books, she asked: “Why does everyone talk about my father but no one talks about me?” It was an immense personal tragedy for her. It was possibly the reason why she left Russia and died abroad.

Her attempts were futile, so she became obsessed with a popular saying of the time: “Nature rests on the children of geniuses.” She decided that nature rested upon her. She didn’t get married because her father’s worldwide fame coincided with the time of her coming-of-age, so she ended up distancing herself from eligible bachelors and other young people who wanted to get acquainted with her. She was well disposed towards the governor of Staraya Russa and expected to find favor in his eyes in return. She wrote to her mother how she had met the governor on a railroad platform beside a train but he paid no attention to her. Liuba was friends with Lev Lvovich Tolstoy, Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy’s descendant. They wrote playlets together. But nothing came of their friendship either. In general, she was known as a “tough cookie.” Dostoyevsky himself would write about his six-or-seven-year-old Liuba: “What will become of her? She has certain traits that worry me a lot.”

My grandfather, the writer’s son Feodor Feodorovich, possessed a radically different character. Clearly, I feel that he and I have a lot of things in common. When Feodor Mikhailovich left for the opening of the monument to Pushkin in Moscow, where he delivered his famous Pushkin Speech, his wife Anna Grigoryevna wrote to him: “I don’t know what to do with Fedya—he is constantly sneaking away from home only to be found later in a company of local kids; all he is interested in is horses.” He wrote back: “Just buy him a colt to keep him busy and he won’t run away anymore.” And that’s what she did. In his next letter, hoping that his son already had the colt, Feodor Mikhailovich sends it a kiss along with the rest of the family. It became an almost mystical, prophetic prediction that Feodor Feodorovich was to dedicate his life to horses. Even at such a tender age, his father had pinned down so accurately a major interest in his son’s adult life.

It is rather sad that teaching science never followed Dostoyevsky in his footsteps. First of all, he never used the expression “to bring someone up” in his letters to Anna Grigoryevna but instead had words like “observe” or “guide.” His principle wasn’t about the children catching up and being on par with the grown-ups that made the parenting job easier but about understanding the child. It yielded excellent results.

Overall, Feodor Mikhailovich grieved over the fact he had started a family so late in life as it meant he wouldn’t be able to guide them to maturity. “How I wish my little children were to have grown up as independent human beings as did yours,” Feodor Mikhailovich wrote to his brother Andrey Mikhailovich, whose children were almost the adults at the time. He treated it as a great personal tragedy that due to his advanced age, he probably wouldn’t see his children as adults.

—When did you realize you were the Dostoyevsky?

—I remember how my mother (it was after the war) decided I was smart enough to understand that I am related to a great man, so she told me about him. She added: “Only, you can’t tell it to just anyone; keep it to yourself.” Because at the time, Feodor Mikhailovich was considered a counter-revolutionary writer. The walls of my school’s literature class were lined with portraits of Dobrolyubov, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Nekrasov—overall, there was everyone but Dostoyevsky. He just didn’t exist. So, I’ve got nothing but my genes and a great desire to study the life and creative activity of my great-grandfather. I think I am very similar to Feodor Mikhailovich in character. Therefore, I am genuinely interested in finding out what kind of a man he was, what he was like as a family man and a writer, what life was like for his ancestors and descendants.