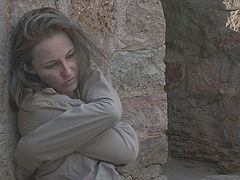

Autumn is over, but the depression and despondency associated with it are not: There is too much global negativity around us. There is the pandemic, lockdowns, economic crisis, and the fear of losing freedom in the era of QR-codes. This is against the background of the sacralization of “depression” in social media. We asked some Russian pastors about how to accept these troubles and not to lose heart, how to overcome the anxiety and apathy that come from the awareness that nothing depends on us. We will be posting these discussions in four parts.

Archpriest George Balakin, the Diocese of Gorno-Altai:

Archpriest George Balakin This question raises two problems. The first is “social media”, and the second is “depression”.

Archpriest George Balakin This question raises two problems. The first is “social media”, and the second is “depression”.

Most often the one whom (or even “what”) we meet in social media is not a real person, but a character, an image, a role. The one who appears on the internet as a depressive melancholic in real life often turns out to be a psychologically stable and even cheerful person. And vice versa—a virtual “cheerful optimist” in real life may be in a prolonged depression. But these are extreme examples. In the middle is the mass of people in social media who play the roles that talents and opportunities allow them. The roles of “trolls”, “haters” and others like them do not require education, talents or even elementary effort. The best thing to do with these characters is simply not to have contacts with them: Ignore, limit communication or ban them—it is not a sin. There is a stereotype that “since we are Orthodox, we must endure”. But it seems to me that this is an erroneous stereotype. It is important for both Orthodox and non-Orthodox to be able to establish and respect personal boundaries.

That is, if instead of a real person we meet a “character”, we must understand that we cannot help here in any way...

But what if this is a real, lonely and suffering person? After all, what we easily define as “depression” may be rooted in the spiritual sphere (the passion of despondency), in the mental, and even physical, somatic sphere. If we do not see reasons for this state, do not have the necessary skills to provide psychological assistance, do not have enough time and energy to share in other people’s pain and problems, then maybe it is better not to violate the personal boundaries, but simply to pray for this person? That is, by showing sympathy, ask for help from the One Who sees every soul and can do everything. Sometimes such help proves to be the most effective and fruitful...

But what if a real and close person finds himself in real depression? Here, in addition to prayer, sensitivity, attention and tact are needed. Sometimes help from outside is vital. But, again, depression (like addiction) cannot be cured by any external means and actions. The most we can do for a loved one is to create conditions where he himself will want to get out of this state.

And, finally, if you have noticed all the signs of depression, you shouldn’t “sacralize” it or shift the responsibility for your bad state to others. You must look for a real and available solution. Sometimes a person just needs to get enough sleep or eat a bar of chocolate. Sometimes he has to work for months and years.

In the Holy Scriptures there is a whole Book devoted to this problem, and it is called Ecclesiastes. Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity. What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun?... All is vanity and vexation of spirit (Eccles. 1:2-3, 14). And it goes depressingly and hopelessly from chapter 1 to 12... But suddenly at the end of chapter 12 there is optimistic advice: Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God, and keep His commandments: for this is the whole duty of man. For God shall bring every work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good, or whether it be evil (Eccles. 12:13-14).

Who are “Orthodox Christians”? Those who were baptized in the Orthodox Church? Or those who go to the Liturgy every Sunday?... I have served as a priest for almost three decades, but I still cannot call myself a full-fledged Orthodox Christian.

More precisely, I want to be an Orthodox Christian, I am learning to be one, but not everything works out. For example, I believe in God to the extent that I accept all the statements of the Nicene-Constantinople Creed without the slightest doubt, but I have not learned to trust God as the Almighty. Or I understand that the commandments of Christ, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself (Mt. 22:37–39), is the highest and most beautiful thing that life can be based on, but how can I fulfill it? How can I love God Whom I have never seen? How can I love my neighbor? And who is my neighbor? (Lk. 10:29).

So if I were one hundred percent Orthodox in name, in life and in essence, I would not have the slightest problem with trusting the Providence of God... But since I am “not a magician, but only learning,"1 it means that I err, stumble and stumble again... But there are those “Orthodox” who stand even further away from normal life in the Church. In this case, we “modern believers” have not lost these virtues because we have not even acquired them yet. So we have no time to be distracted by all sorts of depressions. It is necessary (before it is too late) to learn not only to believe, but also to trust and learn; not only to be called, but also to be.

By the way, thank God, I am aware of many examples even among modern Christians who have succeeded in this.

There is probably no “magic pill” or “miracle button”. There is the following ancient Patristic advice: “Pray, work—and the time of life will pass imperceptibly.” You ask how not to lose heart during the pandemic. But how didn’t our fathers and grandfathers lose heart when the Nazis reached the Volga? How didn’t the Christians of the 1920s and 1930s lose heart when faith in God was a criminal offense in the USSR? How didn’t Russian people who lived along the edge of the Wild Fields2 lose heart when for centuries their villages were regularly burned, fields trampled down, and the population “cleansed” dramatically by nomads during wild raids? It is untrue that “nothing depends on us.” There is always something that does not depend on me in my life, but there is also something that depends only on me. For example, it does not depend on me what the weather is like today, but it depends on me whether to go out in this weather or not, dress according to the weather or not. It is the same with the pandemic, restrictions, and inflation...

Whether to be vaccinated or not, observe self-isolation and social distancing or not, use personal protective equipment or not—this is the choice we are offered. Therefore, to say that nothing depends on us at all is probably wrong... Moreover, we can say that from a certain perspective the pandemic gives us even more freedom. The freedom to express ourselves in relation to God, the Church, and our neighbor... It is no secret that many “Orthodox” have stopped going to church for fear of infection, but continue to go to shops and even places of entertainment.

But we should not forget the most important thing: Orthodoxy is the religion of the Risen Christ! The life that we live is only the beginning of Eternal Life, the True Life. If the Lord has allowed the coronavirus to affect someone, it means that it is not only the cause of the illness, but also, to some extent, a cure for a deeper illness—that of the soul. We need to look at everything that happens not only from the perspective of a hospital ward and death, but also of the future resurrection.