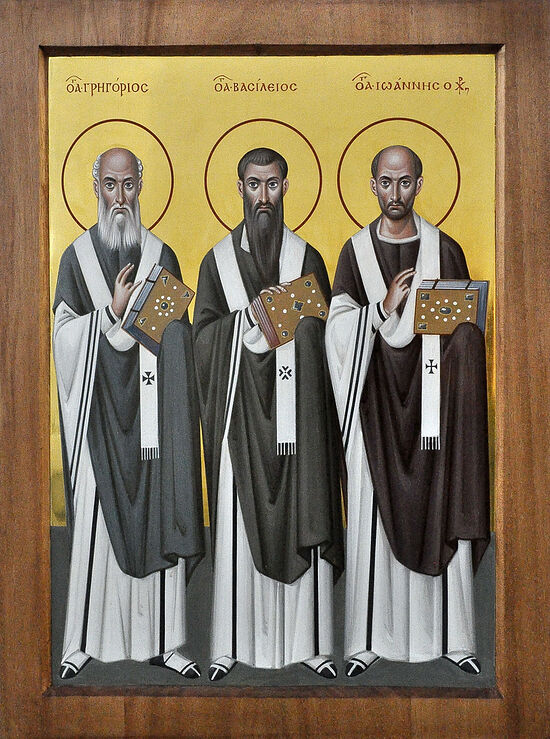

On February 12 we celebrate the Synaxis of the holy Ecumenical Teachers Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom. The love of believers for these ascetics was so great that divisions occurred in the Church. Some called themselves Basilians, others Gregorians, and others Joannites. By Divine Providence in 1084, the Three Hierarchs appeared together to Metropolitan John of Evchait and declared that they were equal before God. Since that time they have had a shared feast.

If asked: “How can you prove that Orthodoxy is the true faith in Christ, sanctified by the grace of the Holy Spirit?”, I would answer: “Because it was in the Orthodox Church that people like Sts. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom lived, served and labored.” For me the appearance of such saints in the Church is physical, biological, historical and spiritual proof of the existence of God and the presence of His grace in Orthodoxy.

And the second question that I would like to reflect on is why these three people became so important for the Church that they were called ecumenical teachers.

Examining the lives of these saints, we can conclude that they sought only one thing: God. Nothing else mattered to them. They deliberately cut off from themselves all the blessings of the world so that nothing would prevent them from moving up the ladder, to Heaven, to the Lord.

As young men from wealthy families, they could have found themselves worthy beautiful spouses, but instead they went into the wilderness to lead an ascetic life. When others tried to ordain them priests, considering themselves unworthy they went further into the wilderness. Having become bishops, they led an almost beggarly lifestyle. When the time of trials came, they defended the purity of the Orthodox faith unshakably, fearlessly and uncompromisingly.

The “tuning fork” for this article could be the dialogue of St. Basil the Great with the Prefect Modestus, who, on the orders of the Emperor Valens, under threat of torture and the death penalty, tried to persuade the saint to accept Arianism.

The saint answered the prefect: “All this means nothing to me. If you take away my possessions, you will not enrich yourself, nor will you make me a pauper. You have no need of my old worn-out clothing, nor of my few books, of which the entirety of my wealth is comprised. Exile means nothing to me, since I am bound to no particular place. This place in which I now dwell is not mine, and any place you send me shall be mine. Better to say: every place is God’s. Where would I be neither a stranger and sojourner (Ps. 38/39:13)? Who can torture me? I am so weak, that the very first blow would render me insensible. Death would be a kindness to me, for it will bring me all the sooner to God, for Whom I live and labor, and to Whom I hasten. Perhaps you’ve never spoken to a bishop before. In all else we are meek, the most humble of all. But when it concerns God, and people rise up against Him, then we, counting everything else as naught, look to Him alone. Then fire, sword, wild beasts and iron rods that rend the body, serve to fill us with joy, rather than fear.”1

These words lift the veil from the inner world of St. Basil the Great (and of Sts. Gregory and John, as well). Longing for God is the center of life for each of them.

Astounded by this answer, the Prefect Modestus In a report to the Emperor Valens said: “Emperor, We stand defeated by a leader of the Church.”

That is why the “good ground” of the hearts of the three saints brought up an hundredfold (cf. Mt. 13:8). Hence the Divine Liturgies, the sublime theology, which was the basis for the definitions of the Second Ecumenical Council, the commentaries on the Holy Scriptures, the spiritual and saving works for priests, monastics, and laity, and the holy life edifying for posterity. And Jesus said unto them…: for verily I say unto you, If ye have faith as a grain of mustard seed, ye shall say unto this mountain, Remove hence to yonder place; and it shall remove; and nothing shall be impossible unto you (Mt. 17:20). St. John of Kronstadt in his book, My Life in Christ, wrote: “With faith you will be able to conquer everything, and even the Kingdom of Heaven will be yours. Faith is the greatest blessing of the earthly life; it unites a man to God, and makes him strong and victorious through Him. He that is joined unto the Lord is one Spirit (1 Cor. 6:17).”2 The Holy Hierarchs had this faith...

How did they live? How did they acquire the gifts of the Holy Spirit, which allowed posterity to call them Ecumenical Teachers of the Church?

The three saints were almost contemporaries and almost of the same age (with the exception of St. John Chrysostom, who was born seventeen years later). Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian were born in the rich Asia Minor province of Cappadocia (translated from Old Persian as “the land of beautiful horses”). Basil was born in 330 in the administrative center of the Caesarea region to an ancient wealthy family that had practiced Christianity for a long time. Gregory the Theologian was one year his senior; he was born in 329 near the city of Nazianzus, which was part of Cappadocia. John Chrysostom was their younger contemporary. He was born in 347 in the then rich and powerful city of Antioch in Syria, famous for its theological school.

Sts. Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian were bosom friends. Basil came from a noble Christian Cappadocian family. His grandmother preserved the tradition about St. Gregory the Wonderworker. His mother was a martyr’s daughter. Five people from the saint’s family were canonized. Among them are Basil himself, his sister St. Macrina, two brothers—Bishops Gregory of Nyssa and Peter of Sebaste, and another sister, St. Theosebia the Deaconess.

St. Gregory the Theologian was born to a family of righteous Christians. His parents became saints. His father was named Gregory and is known as Gregory the Elder. Subsequently, he became bishop of his native city of Nazianzus.

Both families were wealthy, so the parents could afford to give their children a good education in Athens. It was in Athens that Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian met in their youth and became lifelong friends.

During his training, it became clear to Basil the Great’s contemporaries that a great mind was before them. It was written of him: “He studied everything thoroughly, more than others are wont to study a single subject. He studied each science in its very totality, as though he would study nothing else. Philosopher, philologist, orator, jurist, naturalist, possessing profound knowledge in astronomy, mathematics and medicine, he was a ship fully laden with learning, to the extent permitted by human nature.”3

His closest colleague, St. Gregory the Theologian, wrote about him in his Eulogy to Basil the Great: “Various hopes guided us, and indeed inevitably, in learning... Two paths opened up before us: one to our sacred temples and the teachers therein; the other towards preceptors of disciplines beyond.”4

Some time after receiving his education, St. Basil the Great was baptized, then distributed his possessions among the poor and undertook a journey to monasteries of Egypt, Syria and Palestine, settling down in the deserts of Asia Minor to lead an ascetic life and inviting St. Gregory the Theologian there. They lived in extreme austerity. There was no hearth or roof in their dwelling. The ascetics observed strict food restrictions. Basil and Gregory worked, hewing stones to the point of bleeding calluses on their hands. They had only one garment each (without change): a shirt and a mantle. At night they wore sackcloth to increase their ascetic labors.

Lamps of God cannot be hidden under a bushel. They were called to the episcopate. But for quite a long time, out of humility and the fear of the height of the rank, both fled from offers to become priests and then bishops. St. John Chrysostom did the same. His wonderful work, Six Books on the Priesthood, was written for his friend, who had come to the wilderness, to persuade him to accept the priesthood. But the Lord called His chosen ones to the ministry, and they ascended to it as to their Golgotha.

It often seems to us that our times are the hardest. But for an Orthodox person who sincerely believes in Christ and strives to live according to the gospel commandments, any time is not easy. Analyzing the ascetic labors of the Three Hierarchs, we can say with certainty that they ascended to their episcopal thrones as if ascending the cross.

In his book, An Introduction to Patristic Theology, Protopresbyter John Meyendorff wrote about Basil: “St. Basil ruined his health through tireless ascetic life. He died on January 1, 379 at the age of forty-nine, a little short of the triumph of his theological ideas at the Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople (381).”

Forty-nine years of life, wholly devoted to the Church and its well-being. Despite the victory over Arianism at the First Ecumenical Council, the second half of the fourth century was also very troubled. Arianism, named after Arius, the founder of the heresy who rejected the Divinity of the Savior, was transformed into the heresy of Pneumatomachy, which denied the Divinity of the Third Person of the Holy Trinity—the Holy Spirit. Almost the entire Orthodox East was infected with the heresy of Arianism. Not a single Orthodox church remained in Constantinople. With God’s help, through the efforts of Sts. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and their supporters, the purity of Orthodoxy was preserved and Pneumatomachy was refuted at the Second Ecumenical Council by adding to the Creed the verses about the Holy Spirit and His Divinity.

However, a very difficult and dangerous path lay before the victory.

The aforementioned Cappadocian prefect Modestus, a supporter of Arianism, threatened to remove Basil from his see and punish him physically, and part of his flock refused to obey the saint. An Arian bishop served in Caesarea in parallel to him. Archpriest Georges Florovsky wrote about that time in his essay, “The Eastern Fathers of the Fourth Century”:

“Basil was a pastor by vocation and by temperament… He was a man of strong will… When Eusebius died in 370, Basil was elevated to his see, although not without difficulty and opposition. Several prelates refused to give him their obedience. First of all the new bishop had to pacify his flock, and he achieved this by a combination of authority, eloquence, and charity: earlier, during a terrible famine, Basil had sold the property he had inherited and given all of his money to help the hungry. In the words of Gregory, Divine Providence called Basil to be the bishop not only of Caesarea, but ‘through one city, Caesarea, he is lit up for the whole universe.’ Basil was truly a universal pastor who brought peace to the whole world. When at first he had to fight for his see, it occasionally seemed that the concessions he was making were too great. However, these sacrifices were deliberate because Basil considered that nothing could be worse than a heretical bishop. Basil was forced to keep silence for a long time. He refrained from openly confessing that the Holy Spirit was God, because in the words of Gregory the Theologian: ‘They were trying to catch him clearly proclaiming that the Spirit is God.’ In spite of both Scripture and his own beliefs, Gregory continues, ‘Basil for a long time hesitated to use the proper expression, asking both the Spirit and the true supporters of the Spirit not to take offense at his circumspection. At a time when Orthodoxy was threatened, an uncompromising position taken on a matter of mere words could have ruined everything. The defenders of the Spirit could suffer no harm from a small variation in wording, since they would recognize the same concepts behind different expressions. Our salvation is not so much in our words as in our works.’ Although he was forced to impose caution on himself, Basil ‘granted the freedom to speak’ to Gregory, ‘who, by reason of his fame, would not be condemned or exiled from his homeland.’ As a result of this policy Basil was the only Orthodox bishop in the East who managed to keep his see during the reign of Valens.”5

It was he who blessed his friend, St. Gregory the Theologian, to be elevated to the See of Constantinople.

According to Gregory himself, when he arrived in the Patriarchal See in 378, not a single Orthodox church remained in the Byzantine Empire’s capital. At first Gregory served and preached in the house church of his relatives. He named this church “Anastasios” (“Resurrection”). Subsequently it became a real resurrection of Orthodoxy in Constantinople.

On the Paschal night, April 21, 379, a crowd of Arians broke into the church and began to stone the Orthodox. One bishop was killed, and St. Gregory was wounded. But he did not despair. Patience and meekness were his armor. Soon, by Divine Providence and through the labors of St. Gregory, Constantinople became Orthodox.

Gregory wrote about himself: “I am an organ of the Lord and sweetly by intricacy of song of the Most High I do glorify the King: all atremble before Him.”6 The saint lived in the richest capital of the world as though he still lived as an ascetic in the wilderness. “His food was food of the wilderness; his clothing was whatever necessary. He made visitations without pretense, and though in proximity of the court, he sought nothing from the court.”7 When by various intrigues attempts were made to topple him from the Patriarchal throne, he responded gladly, saying: “Let me be as the Prophet Jonah! I was responsible for the storm, but I would sacrifice myself for the salvation of the ship. Seize me and throw me... I was not happy when I ascended the throne, and gladly would I descend it.”8 Gregory sacrificed himself for the sake of peace in the Church.

He died on January 25, 389 in Arianza, a secluded place dear to his heart. The Holy Orthodox Church gave him the title “the Theologian”—one of only three saints in history to hold it—the other two are the Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian and Simeon the New Theologian. This title is given to those saints who through their spiritual writings especially contributed to the revelation and affirmation of the dogma of the Holy Trinity.

The life of the third hierarch, John Chrysostom, was similar to that of St. Gregory. He ascended to the See of Constantinople, which became a second Golgotha for him. With his golden mouth he uncompromisingly denounced the dissolution of morals: hippodromes, theaters with their depravity and bloodthirstiness, etc. Empress Eudoxia was displeased and began to look for ways to remove St. John from his see. An unrighteous council was held and it was decided to put the saint to death. The Emperor replaced the execution with exile. But people who dearly loved John Chrysostom defended their pastor. In order to avoid bloodshed, the saint voluntarily gave himself up into the persecutors’ hands. Suddenly a terrible earthquake occurred in Constantinople, and Eudoxia, frightened, restored John Chrysostom to his see. But two years later, in March 404, another unrighteous council deposed the saint and put him under arrest. He was sentenced to exile in the faraway Caucasus Mountains. The soldiers who escorted him were given a task: “If he does not reach the place of exile, it will only be better for everyone.” One can imagine how hard the “journey” of the aged John was. Indeed John Chrysostom did not reach the place of exile. Exhausted by illnesses, he died in the village of Comana in the Caucasus.

Near the tomb of Martyr Basiliscus this saint appeared to him and said: “Be of good cheer, brother John! Tomorrow we will be together!” St. John Chrysostom partook of Holy Communion and with the words, “Glory to God for all things!”, departed to the Lord. This happened on September 14, 407.

Several decades later his relics were solemnly translated to Constantinople. They were found absolutely intact and were enshrined in the Church of Martyr Irene. Emperor Theodosius II asked the saint’s forgiveness for his parents. People streamed to their beloved saint’s relics. When they exclaimed to John Chrysostom: “Ascend to thy cathedra, O father!”, the holy Patriarch Proclus and the clergy saw St. John Chrysostom open his mouth and heard him say: “Peace be unto all.”

So once again the truth of God triumphed over evil. Therefore, we should not lose heart in our troubled time. The great saints, as we see, endured sorrows. And the Church of God has always been persecuted. But he that shall endure unto the end, the same shall be saved (Mt. 24:13). The life of an Orthodox Christian is bloodless martyrdom. Purifying our souls in the crucible of the severe trials of the times, preserving the purity of the Orthodox faith, following the path of the gospel commandments, we make our souls great treasures in the eyes of the Lord. May He grant them (our souls) the Kingdom of Heaven through the prayers of Sts. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom.

Holy Fathers Basil, Gregory and John, pray to God for us!