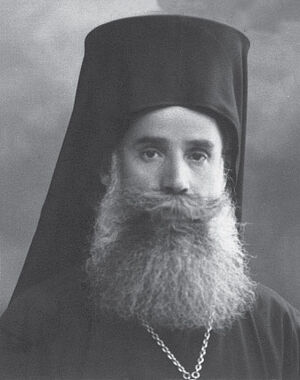

Metropolitan Boris of Nevrokop Is it possible to preserve holiness and piety in the face of the persecution of the Church? History shows that in every age, even in the years of the most terrible persecutions, the ascetic life was possible, and the persecution of the faithful never interfered with personal holiness. And although we have a number of examples when an ascetic managed to survive in difficult times, personal holiness and standing for truth did often lead to confession and martyrdom. One such example is the life of the Bulgarian Metropolitan Boris (Razumov) (1888-1948).

Metropolitan Boris of Nevrokop Is it possible to preserve holiness and piety in the face of the persecution of the Church? History shows that in every age, even in the years of the most terrible persecutions, the ascetic life was possible, and the persecution of the faithful never interfered with personal holiness. And although we have a number of examples when an ascetic managed to survive in difficult times, personal holiness and standing for truth did often lead to confession and martyrdom. One such example is the life of the Bulgarian Metropolitan Boris (Razumov) (1888-1948).

The life of this archpastor was closely connected with the Russian Church and the Russian emigration. Unfortunately, little is known about him in Russia and beyond. A book, Metropolitan Boris of Nevkorop, by Hieromonk Viktor (Todorov) and S. Mukhova recently came out in the hierarch’s homeland, but the study is written in Bulgarian and inaccessible to the foreign reader. Moreover, even in such a voluminous and interesting book, the circumstances of this remarkable hierarch’s tragic death aren’t fully investigated. The documents of the Russian Federation State Archives help clear up the picture.

Metropolitan Boris was born in 1888 in the village of Gyavato near the city of Bitola in the Ottoman Empire (now in North Macedonia), and given the name Vangel. The family was pious, and the future Metropolitan was acquainted with Church life from early childhood. A decisive event in his life was when he met Exarch Joseph I, the head of the Bulgarian Church, who later became his patron.

Vangel graduated from the Bulgarian Seminary of St. John of Rila in Constantinople. The future archpastor had a variety of gifts, such as writing poetry and the ability to learn languages. For his success in learning the Turkish language, he was awarded a golden watch by the Turkish Ministry of Education. Over the course of his lifetime, he also learned Russian, Greek, German, French, English, Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian.

At twenty-two years of age, Vangel Razumov became a monk with the name Boris, and continued his education at the Theological Faculty of the Chernivtsi University in Austro-Hungary, where they taught in German. In 1915, Fr. Boris received a doctorate in theology. In 1917, he was ordained a hieromonk, and in 1922, with the rank of archimandrite, he became the protosingel of the Sofia Metropolis and rector of St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral.

This period coincided with terrible upheavals. With the support of the Comintern in Bulgaria, a communist coup began according to the Russian model. Weapons were delivered to the country, propaganda was carried out, and armed units were created. On Holy Thursday, 1925, the communists staged an explosion in the Cathedral of St. Nedelya during a service. The dome fell, killing 140 people and wounding another 500. It’s unknown how these events would have ended if not for the help of the Russian white emigration. Yesterday’s officers and soldiers were able to rally, arm themselves, and fight back against the red militants.

Archimandrite Boris actively resisted the coup attempts. He stated that none of the cultured European countries had such a tolerant attitude towards atheistic and socialist views as in Bulgaria, and that false teachings brought from outside were corrupting and stifling the youth and retarding the development of the country. In the article, “Martyrdom,” published on the fortieth day after the terrorist attack, the pastor sharply denounced this crime. In his articles, he constantly showed that communists and materialists have no other path but that of crime.

In 1930, Fr. Boris was consecrated Bishop of Stobi and became the Synod’s chief secretary. The high authority of Metropolitan Boris is evidenced by the fact that from the spring of 1932, he was engaged in unofficial reconciliation negotiations between the Churches of Constantinople and Bulgaria, which were conducted through the mediation of the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Unfortunately, the dialogue didn’t brought no results at that time.

In 1935, Bishop Boris became the Metropolitan of Nevrokop.

There were many problems in the life of the Church. Contemporaries noted the low educational and sometimes moral level of the clergy. The Nevrokop Diocese was no exception—there were only three priests with a higher education: One had a legal degree, another philosophy; only the third had a theological degree. The archpastor believed he needed to correct the priests by his own example. He forbade the clergy from giving him any gifts, including money, and ordered them not to demand payment for public services.

During his thirteen years of administration of the metropolis, thirty-three new churches were opened and many old ones were restored, seven Orthodox brotherhoods were founded, and pastoral-theological courses were organized. Contending with the vices of the clergy, the archpastor forbade them to go to drinking establishments and even defrocked several priests who abused alcohol.

The Holy Hierarch was known for his humility and simplicity. For example, he sometimes personally took a priest’s salary to him, wanting to see what conditions his clergy lived in. One time the Metropolitan went to the house of a certain priest. The door was open, but no one was home. The neighbors said the priest and his wife were working in the field. Then the Metropolitan went into the house, tidied everything up, and cooked dinner. When the owners returned, the priest began to weep, he was so touched. Metropolitan Boris didn’t stay for dinner, but gave the priest his stipend and went to give money to another cleric.

1944 came, and the Red Army was approaching Bulgaria. “Ominous clouds are hanging over Bulgaria,” St. Seraphim (Sobolev) wrote in his prayerful request to the Lord. “The Bolsheviks are approaching Bulgaria. Don’t let them come here… Gladden us!”

But, on September 8, 1944, the Soviet troops entered the country. Metropolitan Boris had four years to live. He continued to actively participate in Church life, for example, joining the Commission for Negotiations with the Church of Constantinople. In March 1945, relations were established, and Constantinople recognized the autocephaly of the Bulgarian Church, putting an end to the division that had lasted since 1872.

And yet Metropolitan Boris’ main task during these years remained the struggle for the Church in conditions of persecution, which began almost immediately after Soviet troops entered Bulgaria. A coup was carried out in the country on September 9, and the Fatherland Front came to power, with the communists playing a lead role. Soon, as in the Soviet Union, they became the only party in the country. Political terror had also unfurled.

The new authorities immediately began persecuting the clergy—perhaps not as terribly as in the Soviet Union, but quite tangibly for the small country.

Ideological pressure on the Church also began. They created the Septemberists organization—the Bulgarian version of the pioneer organization in the Soviet Union. One of the organization’s goals was the atheistic education of the youth. In January 1945, Church marriage lost its force. In May 1946, the communist leader George Dimitrov announced the task of creating a “genuine national, republican progressive church” in Bulgaria, hinting at the same time that opposition from the Church could lead to persecution after the soviet model. Dimitrov also pointed out the need for believers to support communist ideas.

The trends observed in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s began to be noticed in the Bulgarian Church. Firstly, this included attempts by so-called “progressive” clergy to seize Church authority; secondly—modernism; and thirdly, and perhaps the most terrible and egregious—the sympathy of some clergy for communist ideology.

A striking example of this was the Clergy Congress in Sofia in 1948. There were no icons in the meeting hall, but there was a giant portrait of Dimitrov. The Congress’ resolutions about building a socialist society were obviously inspired by the ideas of the heresy of Chiliasm about the “millennial Kingdom of God.” In Bulgaria, this heresy was previously spread in the form of so-called Good Samaritanism. Among the priests could be found members of the Communist Party, to whom the authorities left party tickets, giving a directive not to openly speak out against the Church. One such figure managed to deliver atheist lectures and the next day calmly serve the Liturgy.

The Communist Party of Bulgaria relied precisely on this group of clergy. The fact that some of them supported Hitler during the war didn’t interfere with their successful careers. On the contrary, priests with a tarnished reputation were promoted in every possible way by the new government, since it’s much easier to manage such people. The state imposed second marriages for the clergy upon the Bulgarian Church.

An attack on the monasteries began. The main Bulgarian holy site, Rila Monastery, was turned into a resort for tourists, and the monastery was formally closed. The monks were simply systematically squeezed out. Night services and early Liturgies were canceled, and young monks were transferred to other monasteries and parishes. In the end, two or three monks remained at Rila Monastery, and they preferred to live in sketes.

Part of the hierarchy of the Bulgarian Church understood that the Russian experience could help overcome the problems of Bulgarian Church life. The Russian party in the Bulgarian Church opposed modernism and opportunism. For example, the Exarch of the Bulgarian Church, Metropolitan Stefan (Shokov), spoke in support of Russia, which was a clear act of heroism for Bulgaria, which was in an alliance with Germany. The Exarch sent young priests to train at the Russian Church of St. Nicholas in Sofia.

Metropolitan Boris acted the same way. In his diocese, the archpastor tried to appoint Russian priests as the deans. Another of the archpastor’s tasks was to attract Russian monks to Rila Monastery. As the Synodal Secretary, Metropolitan Boris had the opportunity to carry out this endeavor and create a genuine spiritual monastic center there. However, the Holy Hierarch wasn’t supported by the Synod in this matter.

The Metropolitan also struggled with the extremes of ecumenism, which grew into religious indifference with some representatives of the Bulgarian Church. On June 1, 1948, at a meeting of the Synod, he declared that ecumenism in the form proposed by the Bulgarian modernists should be condemned in principle. The proposal was supported by all the metropolitans who were at the meeting. The Synod unanimously decided to sever all relations between the Bulgarian Church and the ecumenical movement.

Additionally, Metropolitan Boris sharply opposed the communists. He categorically forbade the clergy to join the “Union of the Fatherland Front,” and to join the Workers’ (Communist) Party. He boldly helped the families of repressed priests and directly announced a collection of assistance for the arrested.

The Metropolitan’s actions can, without exaggeration, be called heroic. The thing is that the Nevrokop Diocese, including Pirin Macedonia, was considered by the new authorities as a stronghold of “capitalism and fascism.” There were detentions and shootings there, and forty-five priests were arrested in the Nevrokop Diocese in those years, three of whom suffered unto death. The Metropolitan’s position was an open challenge for the Reds. As a result, the Pirin Macedonia administration declared Metropolitan Boris “enemy of the people’s power No. 1.”

At the same time, Metropolitan Boris enjoyed great authority among the common folk. It was impossible to deprive him of his See or arrest him—let’s not forget that this wasn’t the Soviet Union. But the authorities were looking for a reason to get rid of him. The State Security started surveilling the hierarch, and his every movement was recorded. Informants reported about everything he said, and the Metropolitan spoke very openly in his sermons; for example:

“A state, or any other organization that has no faith in God, will perish sooner or later.”

“Every one of us, no matter who or what we are… must know that God, Who created us, is above all… Don’t rely on any teachings that deny God.”