There are three major monasteries in Bulgaria: Rila in the southwest (a World Heritage site), Bachkovo in the foothills of the Rhodope Mountains to the south, and Troyan in the Balkan Mountains in central Bulgaria.

But aside from these three major sites, there are many monasteries dotted about Bulgaria, in particular around the capital, Sofia, and many of these are inactive or abandoned. The monasteries around Sofia make up what is known as “the Little Holy Mountain”, a reference to the Holy Mountain, Mount Athos in Greece, famous for its monasticism.

You can be in Sofia and not realize that there is a different experience awaiting you only twenty minutes by car from the capital. Unfortunately, many people don’t get this opportunity to travel further afield or don’t know about these places. When you leave Sofia, you enter a different world, one of beautiful nature and one of great spirituality. We do not realize that nature has its own language and it takes time to begin to decipher it.

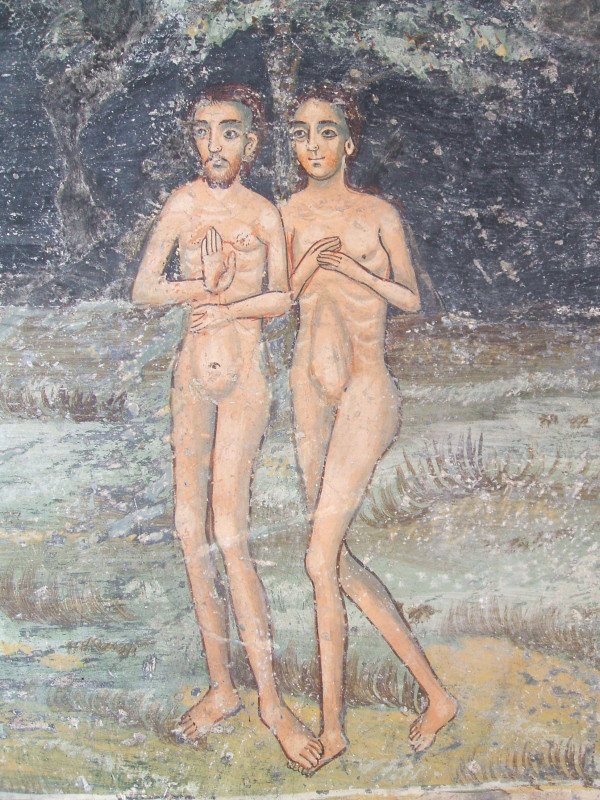

The Bulgarian poet Tsvetanka Elenkova and I visited 140 monasteries from our home in Sofia during the period 2006–2012. The fruit of this pilgrimage was a series of ten essays by Tsvetanka contained in a book published in Bulgarian as Bulgarian Frescoes: Feast of the Root (Omophor, 2013), accompanied by more than a hundred of my photographs. These essays cover different feasts, from the Nativity of Christ to his Resurrection and Ascension. We have made a small selection of the best images to give people an idea of the riches hidden away in monasteries in Bulgaria that are often abandoned and can be difficult to get to.

The best example is Seslavtsi, a district of Sofia twelve northeast of the capital. The frescoes here are breathtaking. They were painted by a famous iconographer, Pimen of Zograph, a monk from the Bulgarian monastery of Zograph on Mount Athos who was called by St George in a dream to return to his homeland and to build and paint churches, which he did at the start of the seventeenth century, four hundred years ago. The church containing these frescoes was used for target practice during Communism and is next to a uranium mine. The quality of the frescoes is so good that attempts have been made to cut them out of the wall and take them. The frescoes have not been restored, which gives them a lifelike quality. Once frescoes are restored, they lose something of their spontaneity and acquire a sheen.

Other monasteries containing high-quality frescoes in the environs of Sofia are Alino, a village on the south side of Mount Vitosha, the mountain that overlooks Sofia from the south; Eleshnitsa, a village 25 km north-east of Sofia; and Iliyantsi, a district of Sofia in the north.

Further afield, we find the church of Berende, a village 50 km north-west of Sofia in the direction of Serbia, overlooking a disused railway and with wonderful autumnal colours. Not far away from Berende is the village of Malo Malovo, a very difficult monastery to find. Our first attempt was unsuccessful. We were with our year-old baby and unexpectedly came across some young lads hanging out in the mountain. We caught the glint of metal, beat a hasty retreat and returned a week later, this time without our child, successfully locating the monastery, which was hidden away behind an elevation, perhaps deliberately if one considers that a lot of these monasteries were built during the Ottoman occupation of Bulgaria in the fourteenth-nineteenth centuries, when churches were not supposed to exceed the height of a man on horseback and so had to be dug into the ground.

To the north-east of Sofia, still in west Bulgaria, we find Strupets and Karlukovo. To the west of Sofia lies Bilintsi, on the road to Tran, which has a very attractive gorge. Here, we came across a monk who had taken it upon himself to paint over the old frescoes and who kindly offered us tea in the hovel he was living in (which had a large hole in the ground). Fortunately, his work of ‘restoration’ was incomplete and we were able to photograph some of the original frescoes.

South of Sofia, near the motorway to Greece, is Boboshevo, another excellent monastery for frescoes. And then in central Bulgaria, we have Arbanasi, a hill with old churches next to the medieval capital Veliko Tarnovo. One of these churches is the Church of the Nativity, an example of a building that is sunk into the ground, with sumptuous frescoes inside. A little to the north of Veliko Tarnovo, overlooking the river Yantra, with Holy Trinity Monastery on the other side, is Preobrazhenie (Transfiguration) Monastery, which has a wonderful Wheel of Life fresco on the outside.

These are only some of the monasteries we visited, but they are the ones with the most important images. Our aim in presenting these images is to show the high quality, the naivety (we must become like children to enter the kingdom of heaven), the deep spirituality of Bulgarian frescoes. In the West, our attention is drawn to the likes of Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel, considered a high example of religious art. Some of these monasteries—Seslavtsi, in particular—can quite rightly be included in the same canon of European religious art.

English and French editions of the book Bulgarian Frescoes: Feast of the Root are forthcoming.

Captions by Tsvetanka Elenkova, photographs and translation by Jonathan Dunne.