Photo: bg.wikipedia.org Starting in 1948,the Bulgarian Communist leadership, backed by the Soviet Union, launched a campaign to destroy the Russian party in the Bulgarian Church. Despite the fact that Russian party representatives spoke out against Hitlerism during the war and participated in the resistance, now they were being accused of fascism. Bishops and priests who gravitated towards Russia and the Russian Church didn’t receive high posts in the Bulgarian Church. Clouds had gathered over St. Seraphim (Sobolev), the head of the Russian parishes in Bulgaria. After his harsh denunciation of the Bulgarian Renovationists, the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church considered sending Archbishop Seraphim into retirement. The Holy Hierarch’s death in February 1950 interrupted these plans.

Photo: bg.wikipedia.org Starting in 1948,the Bulgarian Communist leadership, backed by the Soviet Union, launched a campaign to destroy the Russian party in the Bulgarian Church. Despite the fact that Russian party representatives spoke out against Hitlerism during the war and participated in the resistance, now they were being accused of fascism. Bishops and priests who gravitated towards Russia and the Russian Church didn’t receive high posts in the Bulgarian Church. Clouds had gathered over St. Seraphim (Sobolev), the head of the Russian parishes in Bulgaria. After his harsh denunciation of the Bulgarian Renovationists, the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church considered sending Archbishop Seraphim into retirement. The Holy Hierarch’s death in February 1950 interrupted these plans.

Another pro-Russian archpastor, the Exarch of the Bulgarian Church Metropolitan Stephan (Shokov), was sent into exile in 1948 to the distant village of Banya, where he spent the rest of his days under virtual house arrest.

But most tragic was the fate of Metropolitan Boris.

The archpastor foresaw his death. When a friend once advised him to be careful, because he had been sentenced to death, Vladyka replied:

“Are you against me becoming a martyr? And what if I want it myself?”

Shortly before his death, he went to see his close friends, and said:

“I’ve urgently come to say goodbye.”

Then he clarified:

“Yes, yes, to say goodbye. This is the last time we’ll see each other. I received a sign last night that my end is nigh. I dreamed that some fire fell from Heaven, and this fire grabbed me and carried me away to Heaven. It’s true. This is the end for me.”

On November 8, 1948, Metropolitan Boris consecrated the Church of St. Demetrios of Thessaloniki in the village of Kolarovo. At the end of the Liturgy, he preached about the feat of the Great Martyr Demetrios, noting that a Christian shouldn’t fear death, but should be ready to meet it. After the service, the archpastor, clergy, and guests went to the trapeza.

At that time, a man named Ilya Stamenov came to the church and started demanding to see the Metropolitan. Apologizing to his guests, the archpastor went out into the hallway, and soon everyone heard shots. Running out of the refectory, everyone saw the dead Metropolitan. Stamenov didn’t try to escape, but immediately went to the authorities and surrendered.

The criminal’s story was interesting. He was once a priest. In 1935, he was suspended for spilling Communion, but after three years he was forgiven. In 1942, he was suspended again—this time for stealing alcohol. After that, the crook got interested in political affairs, and was involved in the extradition of anti-fascist partisans. In 1944, Stamenov was sentenced to death in absentia by the new Bulgarian leadership, but remained at large.

Of course, the fact that the traitor sentenced to death was alive suggests that Stamenov was involved in the Special Services. This is confirmed by the fact that the investigation into the murder of Metropolitan Boris was classified, being handled not by the police, but by the State Security Service. As often happens in such cases, the reason for the murder was officially said to be personal revenge. Stamenov himself said that he shot the hierarch for refusing to restore him to holy orders.

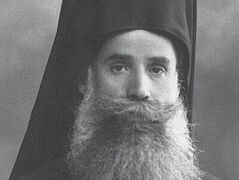

Met. Boris serving a moleben on November 14, 1937. Photo: bulgarian-orthodox-church.org

Met. Boris serving a moleben on November 14, 1937. Photo: bulgarian-orthodox-church.org

Metropolitan Boris’ death was another victory for the communist authorities in Bulgaria. The Nevrokop Cathedra was vacant for a time, and the authorities wanted to impose Bishop Pimen (Enev) into this position. St. Seraphim (Sobolev) spoke negatively about him and testified that absolutely all Bulgarian hierarchs had opposed his consecration to the episcopate. Nevertheless, it was precisely such people that the Communist state promoted. In 1953, Bishop Pimen became Metropolitan of Nevrokop.

The subsequent life story of Metropolitan Pimen is quite interesting. In 1992, he became one of the organizers of the “Pimenov” schism and even declared himself “Patriarch,” and participating in his enthronement was the infamous Philaret Denisenko, who had also gone into schism by that time. And although a year before his death, Pimen formally reconciled with the Bulgarian Church, his career again testifies to what kind of people the so-called “People’s Democracy” recruited for Church personnel.

We should also talk about the fate of the killer.

His connection with the Bulgarian State Security Service can’t be formally established. The court was closed, and all important investigative documents were destroyed. The Special Services have seriously cleaned up the case of Metropolitan Boris himself. At one time all hierarchs were monitored; they had briefs on all of them, and reports came in from agents. But compared with the cases involving other Bulgarian hierarchs, the case of Metropolitan Boris is marked by a striking scarcity of materials.

Therefore, we have only indirect data about the involvement of the Special Services in his murder.

Above all, this is the person of Stamenov. First, as already mentioned, despite the death sentence of 1944, he not only was alive, but was at large. Second, he received only six years and eight months in prison for killing Metropolitan Boris, but after only nine months he was transferred to work outside prison, taking care of vineyards. And after another two years, Stamenov was pardoned by decree of the Presidium of the Bulgarian People’s Republic. However, the further fate of the murderer can’t be envied. He soon found himself in a psychiatric hospital, where he ended his days constantly repeating: “I killed him, I killed him.”

But let’s return to the bright side of our story—to Metropolitan Boris.

They wanted to bury the Holy Hierarch in the main Bulgarian monastery—Rila Monastery—but the Bulgarian Chekists wouldn’t allow it. Vladyka was buried in Gorna Jumaya,1 at the Church of the Entrance of the Theotokos, with a huge gathering of people. Priest Stefan Khristov testified:

“The body was in an open coffin for four days. He didn’t change, neither in his face or his body. It couldn’t be said that he was dead. People were saying he was a holy man.”

In his eulogy, Metropolitan Mikhail, who served the funeral, called Vladyka Boris “the conscience of the Bulgarian Church,” and St. Seraphim (Sobolev) responded to his death saying: “He departed as a hieromartyr, who kept his hierarchical conscience pure and unblemished.”

In subsequent years, cases of Metropolitan Boris’ posthumous prayerful assistance have been recorded, and in 2016, the Bulgarian Church announced it was preparing to canonize the archpastor.

The Metropolitan’s fate shows how difficult it was in the times of persecution, even in their milder Bulgarian version, to keep one’s conscience clean and to stay safe. As for the first, the Metropolitan succeeded in preserving his conscience. But as for the second—preserving his earthly life—he didn’t manage. But he acquired eternal life, and perhaps it’s thanks to the prayers of people like Metropolitan Boris that our world still exists today.