We’re forever doomed to choose between good and evil, and the tragedy of our choice is further exacerbated by our wavering out about the very notions of what is “good” and “evil”…

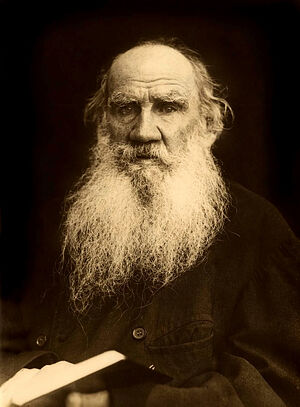

Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy—unquestionably a genius of world literature and a distinguished thinker—has an expression: “The mind of the mind and the mind of the heart.” The mind is tricky! It can explain everything exactly how a man lost in the labyrinths of pride wants to hear it. It’s the heart that perceives the Truth—Christ! Only the heart knows the path to Salvation! And the heart needs no explanation!

All the grace of the Spirit contained in the Church’s Sacraments, which Count Leo Tolstoy tried in vain all his life to perceive with his mind, is aimed at the purification of the heart. The great mind of the thinker was never able to understand the simplicity of the “mind of the heart.” Therein lies the tragedy of Leo Tolstoy.

Tolstoy’s grave, Yasnaya Polyana

Tolstoy’s grave, Yasnaya Polyana

A grave without a cross

Perhaps only Leo Tolstoy’s own pen could properly describe the chilly dreariness of this grave without a cross.

Neither a cross nor a tombstone adorns the grave of Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy, the greatest Russian writer and humanist, the profound thinker whose life was full of intense and sometimes truly agonizing spiritual searching. At Yasnaya Polyana, the Tolstoy family estate, visitors are still surprised to see the grassy burial mound. The grave is known for its utter seclusion: a grove of oaks and birch trees, a thicket of hazel bushes, a ravine, a forest... Here, in a sunlit meadow half a versti away from the house, not far from the road where Count Tolstoy liked walk to walk every morning, where the writer’s restless spirit found its “eternal rest.” Perhaps only Leo Tolstoy’s own pen could properly describe the chilly dreariness of this grave without a cross.

“I prayed and cried…”

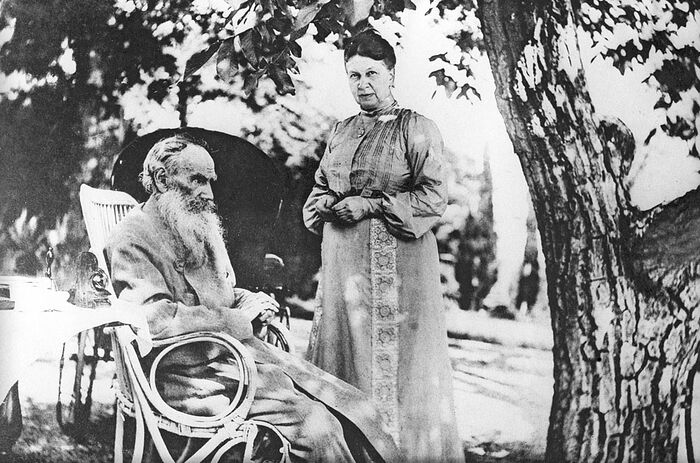

In April 1911, Sofia Tolstoy wrote in her diary:

The day is warm, but windy. I stepped outside for the first time and went, of course, to Leo Nikolayevich’s grave. In the distance, the bells were ringing incessantly. “Christ is Risen!” sounded all over Russia, but there, in the forest, at the grave, everything remained silent; dried wreaths swayed in the wind, and I prayed and cried.

It seems Sofia, Tolstoy’s wife and unfailing assistant, the mother of his thirteen children, couldn’t help but cry over the fact that her famous husband whom she was married to for forty-eight happy-yet-unhappy years, got quite lost in his search of the Truth by developing, with his “solid mind,” a religious and philosophical doctrine that led a great number of people away from Christ. She was probably also weeping over those diary entries Leo left behind regarding their married life, that would now be read by so many people. They would accuse Sofia of being unable to understand her husband’s spiritual quest and of making their family life miserable with all those scandals that provoked mutual hatred. With her desire to firmly “tether” her husband, a man of genius, to “earthly prosperity,” Sofia failed to notice when and how the spiritual bond between them was broken.

“What does it take to bind him?” Sofia Tolstoy would candidly ask in her diary. “I was taught that I have to be honest and love him, and be a good wife and mother. It’s in all the books—but it’s all nonsense! You don’t have to LOVE, but to be cunning instead; you should be smart and hide everything, as there has never been and never will be people without malice. AND, MOST IMPORTANTLY, YOU DON’T NEED TO LOVE.”

How could Sofia, who held on to such an attitude for more than forty years of married life, become Tolstoy’s “ark of salvation” in his desperate spiral of spiritual delusions?

The path to the “earthly paradise”

Questions about the meaning of life occupied Tolstoy already in early childhood. He firmly believed that there exists a “green stick” with the secret of happiness for everyone carved on it, and that all people should become “ant brothers.” Placing great emphasis on moral principles as the binding force of being, and the human mind as a creative, rather than destructive, force, the future great humanist began his search for a path leading to the “earthly paradise.”

At the age of sixteen, Tolstoy replaced his cross with a Rousseau medallion

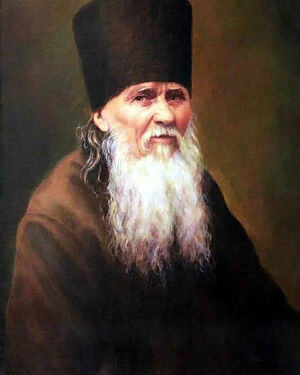

Until the age of fifteen, Leo Tolstoy, baptized in infancy in the Russian Orthodox Church, honored all Church traditions and canons, but his great interest in the philosophical works of the French Enlightenment authors did its part: An ardent opponent of Christianity, Jean-Jacques Rousseau became his “icon” and, at the age of sixteen, Tolstoy replaced his cross with a medallion with a portrait of Rousseau. It was only after forty, as he grew disappointed with this pessimistic philosophy that couldn’t offer any “reasonable answers” for his searching mind, that the writer was forced to admit that it was faith that fills a man’s life with meaning. That’s when Tolstoy again turned to the Orthodox faith: He would frequent the Church services, read theological literature, and hold lengthy conversations with the Optina Elders. His meeting with St. Ambrose of Optina left a great impression upon him, and he often spoke about it:

This Fr. Ambrose is truly a holy man. I spoke with him, and somehow I felt relieved and consoled. When you talk to someone like him, you experience closeness with God.

Venerable Ambrose of Optina St. Ambrose, on the contrary, bitterly lamented as he recalled his conversation with Tolstoy: “What a proud man... so proud...”

Venerable Ambrose of Optina St. Ambrose, on the contrary, bitterly lamented as he recalled his conversation with Tolstoy: “What a proud man... so proud...”

Instead of accepting the Christian faith in his heart, Tolstoy simply explored and interpreted it with his great mind and proceeded to “purify” it from the “irrational:”

“Talking about the Divine and faith has led me to a great and profound thought, and I feel capable of dedicating my life to its realization. This thought is the basis of a new religion that corresponds to the development of mankind—the religion of Christ, but purified from faith and mystery; a practical religion that doesn’t promise future bliss, but offers to live blissfully here, on earth,” Tolstoy writes in his diary.

Tolstoy sincerely believed that, based on “purified religion,” it is possible to create the

“Kingdom of God on earth”

Tolstoy’s great mind ventured to develop its own religion! He began to openly deny the Triune God and considered Jesus Christ simply a great Man; he was unwilling to acknowledge the chaste conception of Christ and His Resurrection; he refused to honor the Sacraments of the Church and the holy icons. From a position of “common sense,” the writer rejected the Old Testament and rewrote the four Gospels of the New Testament, discarding the “unnecessary” parts of Holy Scripture. Tolstoy sincerely believed that, based on “purified religion,” it’s possible to establish “the Kingdom of God on earth among men.”

The writer’s restless spirit never accepted the beliefs of the Christian Church and his “proud mind” desperately opposed the “mind of the heart.” Having written the Critique of Dogmatic Theology in four volumes and having developed “What I Believe” as his religious philosophy, in his Confession, Tolstoy expounded in detail the history and the reasons of his disagreement with the Orthodox Church that he perceived as being a social, political, and economic, but not a spiritual, notion. The fact that Tolstoy criticized the Church in harsh terms means that there was an element of deep personal resentment and undisguised irritation. But, alas, we’ll never know the cause of such resentment. Either way, the harsh criticism of the clergy attracted the attention of the whole world to Tolstoy.

In spite of his international renown, Fr. John of Kronstadt openly stated:

So many spiritually blind men were learning and still learn from Leo Tolstoy, as they avidly read his works and fall into his net, alienating themselves from God, falling into despair and ending their own lives. These are the fruit of the devil’s talent sewn by the enemies of God.

In 1896, К. P. Pobedonostsev, the Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod, in his letter to the former professor S.A. Rachinsky, wrote:

It’s so awful to think of Leo Tolstoy. He spreads that dreadful contagion of anarchy and faithlessness all throughout Russia!.. It’s as if he’s demon-possessed—and what are we to do with him?

Emperor Alexander III used to say in this regard:

Don’t make Tolstoy a martyr, and me his executioner.

Desiring to help Tolstoy to gain insight into his mistakes, a great number of hierarchs of the Orthodox Church entered into correspondence and held conversations with him

Desiring to avoid conflicting misunderstandings among the intelligentsia, who blindly idolized Tolstoy, the Church was loath to attract public attention to the writer’s religious delusion. Wanting to help him understand his errors, many hierarchs of the Orthodox Church entered into correspondence with and conducted lengthy conversations with him, including Metropolitan Macarius (Bulgakov), Bishop Alexiy (Lavrov-Platonov), Archimandrite Leonid (Kavelin)... But all to no avail.

Only when Tolstoy published his huge novel Resurrection (in Russia and Europe!), where he openly mocked the Sacrament of the Eucharist, did it become clear to everyone that it was no longer possible to remain silent, because it brought about an ambiguous situation: Tolstoy called himself a Christian, all the while openly promoting false religious beliefs drastically opposed to Orthodox Christian teaching. The public waited for the Church’s reaction. And the Church responded!

The “Church Bulletin” journal published the “Ruling of the Holy Synod from February 20-22, 1901, № 557 with an address to the faithful children of the Orthodox Greek-Russian Church regarding Count Leo Tolstoy” that officially notified of Count Leo Tolstoy falling away from the Church, because his publicly expressed beliefs were absolutely incompatible with the Orthodox faith.

Was there truly an anathema?!

Leo Tolstoy Many people know the story “Anathema” by Kuprin. Although the story diverges from the historical reality, readers couldn’t help but be moved by the image of a rebellious archdeacon who was so greatly impressed with his nighttime reading of a “charming short novel” by Tolstoy that at the service the next morning, instead of solemnly anathematizing the writer, he proclaimed “Many Years!” to him.

Leo Tolstoy Many people know the story “Anathema” by Kuprin. Although the story diverges from the historical reality, readers couldn’t help but be moved by the image of a rebellious archdeacon who was so greatly impressed with his nighttime reading of a “charming short novel” by Tolstoy that at the service the next morning, instead of solemnly anathematizing the writer, he proclaimed “Many Years!” to him.

Kuprin’s literary fiction fueled public interest in Tolstoy’s “anathematization.” But the fact is that none of the churches of the Russian Empire publicly proclaimed an anathema against Tolstoy! The Synodal decision regarding Tolstoy was simply a statement of the fact that the writer ceased to be a member of the Orthodox Church, that is, he “fell away” from it of his own volition. The Synodal Acts of February 20-22 also stated that Tolstoy could return to the Church were he to repent.

Escape from Yasnaya Polyana

In an attempt to spend the remaining time of his life in obedience to his convictions, the eighty-two-year-old writer decided to “escape” from Yasnaya Polyana to a place where he could find inner peace. In the autumn of 1910, in bad weather and in the darkness and dampness of the night, Tolstoy quickly got ready, trying not to wake anyone, and left the house. Taking no one with him but his personal doctor D.P. Makovitsky, already bumping along the road in a springless carriage, Tolstoy took a long time to decide where to escape to: the Caucasus or some remote village... Then, suddenly, he said firmly: “I’m going to Optina!” The writer’s rebellious soul rushed to salvation—where he could find help and overcome the bitter loneliness from which neither his family nor his world fame could save him.

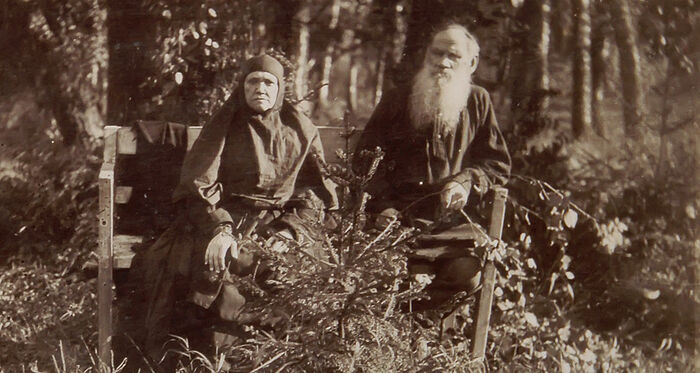

Leo Tolstoy with his sister the nun

Leo Tolstoy with his sister the nun

The Optina Hermitage chronicle for October 28 reads:

The famous writer Count Leo Tolstoy arrived at the Optina Hermitage. Stopping at the monastery guesthouse, he asked the riassaphore novice Fr. Michael, the guesthouse master: “Perhaps you feel annoyed that I came here? I’m Leo Tolstoy, excommunicated from the Church; I arrived to talk to your elders. I am to leave for Shamordino tomorrow.” In the evening, stopping in to see the guesthouse caretaker, he inquired who was the abbot, who was the head of the skete, how many brethren they have, who are the elders, and whether Fr. Joseph was well and accepting visitors. The next day he went for a walk twice. They saw him by the skete, but he neither went inside nor visited the elders and left for Shamordino at 3 PM. There is the following information about the Count’s stay in Shamordino. His meeting with his sister, a Shamordino nun, was quite moving: The Count tearfully embraced her and the two of them then spoke for a while. Among other things, the Count mentioned that he stopped at Optina, and that it was nice there, and he’d gladly wear a cassock and live there doing the lowliest and most strenuous work, but under the condition that he not be forced to pray, which he couldn’t do. When his sister remarked that they also would have stipulated that he wasn’t to preach or teach anything, the Count replied, “What is it that I can teach there? We should learn from them,” and said that the next day he’d go to Optina to spend the night and see the elders. He spoke well of Shamordino, saying he could have shut himself up in his hut there and prepared for death. In the middle of the next day, he was at his sister’s again, but in the evening the Count’s daughter suddenly came and whisked him away at night.

“The Yasnaya Polyana Notes” by Dushan Makovitsky from October 29 reflected what Tolstoy said after his walk near the skete: “I won’t go to the elders myself. Had they summoned me, I’d have gone.” Once more, St. Ambrose’s words about Tolstoy come to mind: “What a proud man... so proud...”

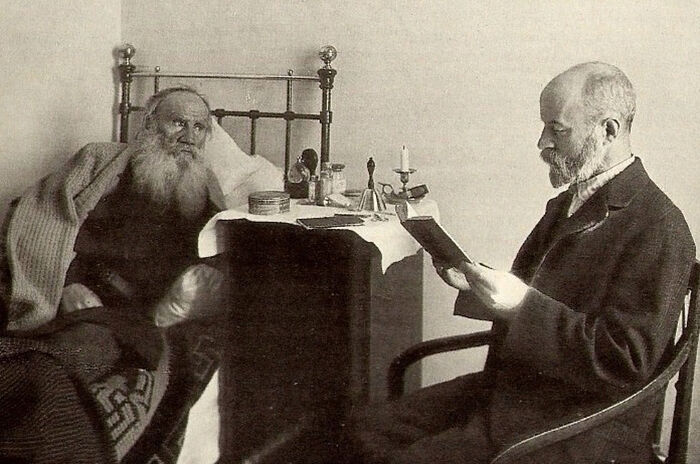

Leo Tolstoy and Dushan Makovitsky

Leo Tolstoy and Dushan Makovitsky

“I won’t go to the elders myself. If they summoned me, I’d have gone,” he said, unable to find the strength to step inside the Optina skete

Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy never found the strength to step inside the Optina skete!

What was on his mind as he was leaving the Optina Hermitage, a place where his tormented soul could find rest? Did he feel the approach of death, which he experienced so many times with his beloved characters? He failed to escape—Tolstoy was once again on his way back to the “earthly paradise” he tried to build according to the laws of his mind.

At the Astapovo station, the writer and his companions had to get off the train—he fell ill with pneumonia. He began to suffocate...

“I really love the truth…”

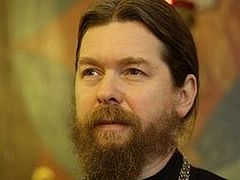

Venerable Barsanuphius of Optina “I think I’m dying... I really love the truth...,” Leo Nikolayevich kept saying feebly, surveying the people gathered at his bedside with bleary eyes. He cried a lot and remained silent for a long time. He couldn’t move anymore, except that the fingers of his right hand continued to move as if he were writing still unspoken thoughts. He asked only for one thing—that his wife not be allowed in to see him...

Venerable Barsanuphius of Optina “I think I’m dying... I really love the truth...,” Leo Nikolayevich kept saying feebly, surveying the people gathered at his bedside with bleary eyes. He cried a lot and remained silent for a long time. He couldn’t move anymore, except that the fingers of his right hand continued to move as if he were writing still unspoken thoughts. He asked only for one thing—that his wife not be allowed in to see him...

Overnight, the railroad junction at Astapovo near Lipetsk became famous all over the world—there, in the house of the station master I. Ozolin, the greatest mind of the time was dying a painful death.

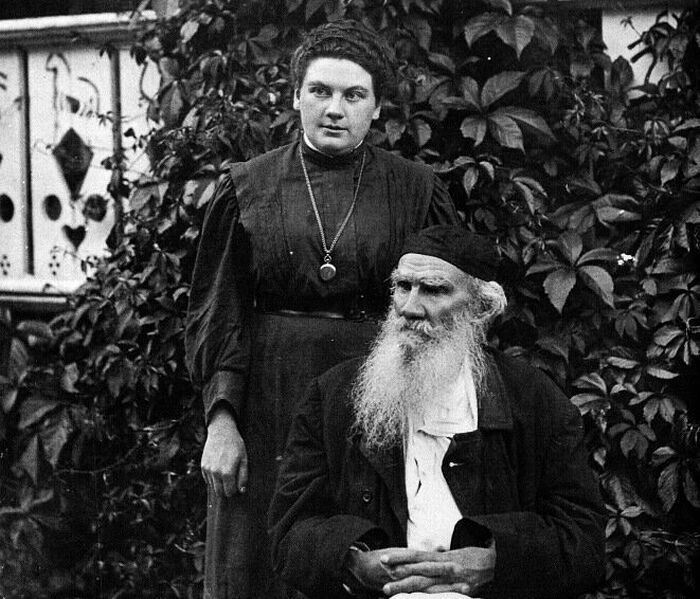

By order of the Synod, Elder Barsanuphius went to Astapovo from the Optina Hermitage to bring the lost sinner back to the Church through the Sacraments of Repetance and Holy Communion, but alas... Alexandra Tolstoy, the author’s youngest daughter, secretary, and follower of his teachings, never let the Elder see her dying father, but delivered a note saying that Count Tolstoy didn’t wish to see him and that her father’s wish was sacred to her. Fr. Barsanuphius replied:

I respectfully thank Your Ladyship for your letter, where you write that the will of your parent comes first for you and your family. But, Countess, you also are aware that the Count has expressed his wish to his sister, and your aunt, the nun Mother Maria, to see and speak with me.

There was no reply. When Tolstoy died, the Elder sent a telegram to Bishop Benjamin of Kaluga:

Count Tolstoy died today, November 7, at 6 AM... He died without repentance. I wasn’t invited.

Alexandra Tolstoy with her father

Alexandra Tolstoy with her father

Alexandra Tolstoy bitterly repented the rest of her life for never telling her father about the arrival of Elder Barsanuphius with the Holy Gifts

The like-minded people surrounding Leo Nikolayevich’s deathbed during the last seven days of his life never thought what a heavy burden they took upon themselves for the “empty quiet” they created around a dying man. Upon his return to Slovakia in 1920, Dushan Makovitsky, Tolstoy’s personal doctor and friend, who called himself a “Tolstovite,” committed suicide in a state of severe depression. Alexandra Tolstoy, who emigrated to America following the revolutionary upheaval in Russia, became a devout Christian, and for the rest of her life, she bitterly repented that, not wanting to excite her gravely ill father, she didn’t tell him about the arrival of Elder Barsanuphius with the Holy Gifts and didn’t show him the telegram from Elder Joseph, who was also ready to come and see Tolstoy on his deathbed...