At what age did people get married in the Russian Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century? From 1840 on, men were allowed to marry at eighteen, and women at sixteen. In accordance with the data of the First General Census of 1897, the average age of marriage was twenty-four for men and twenty-one for women.

Around this time (the second half of the nineteenth century), an ordinary pious peasant family lived in the settlement of Tarnogrod, Bilgoraj district, Lublin province (the Russian Empire; now the territory of Poland). The spouses Foma and Ekaterina Stasevich had no children. Only when the husband was forty-four and his wife thirty-two did the Lord send them their only child—a son. This event took place on March 20, 1884. The boy was named Lev.

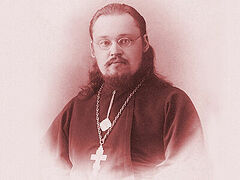

Hieromonk Leonty (Stasevich) Lev’s parents were God-fearing, hospitable, hardworking and sensitive to other people’s misfortune. Wandering pilgrims would often stay overnight in their house. Little Lev would fall asleep to their singing. They sang prayers and spiritual hymns. The boy grew up receiving a Christian upbringing, helping his parents in their peasant labors and studying to the best of his ability.

Hieromonk Leonty (Stasevich) Lev’s parents were God-fearing, hospitable, hardworking and sensitive to other people’s misfortune. Wandering pilgrims would often stay overnight in their house. Little Lev would fall asleep to their singing. They sang prayers and spiritual hymns. The boy grew up receiving a Christian upbringing, helping his parents in their peasant labors and studying to the best of his ability.

After graduating from high school, the fifteen-year-old Lev got a job at the Tarnogrod court as a clerk. Frequent attendance at court hearings had an unexpected result. Having seen enough of the injustice of this world, human malice and human suffering, Lev decided to devote his life to God. He entered the Chelm Theological Seminary, after which in 1910, at the age of twenty-six, he joined the Jableczna Monastery of St. Onuphrius. This monastery was unique in that, despite its westernmost geographical location, it rejected the Catholicism and Uniatism imposed by the West and preserved the purity of the Orthodox faith. Two years later, Lev Fomich was tonsured into the monastic mantia with the name Leonty. In the same year he was ordained hierodeacon, and a year later hieromonk. At the Monastery of St. Onuphrius, Fr. Leonty got to know the perfect monastic life, and this ideal was imprinted in his soul forever.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Fr. Leonty was transferred to the (now defunct) Theophany Monastery in Moscow. Here a fateful meeting took place: One “fool-for-Christ” predicted his future suffering for the faith. “The time will come when they will take you down the street threatening you with rifle butts.” But all this would come later. In the meantime, Fr. Leonty was a student of the Moscow Theological Academy. But he was not destined to finish his studies—the Academy was closed by the godless authorities in 1920. And Fr. Leonty was elevated to the rank of igumen.

The Jableczna Monastery of St. Onuphrius

The Jableczna Monastery of St. Onuphrius

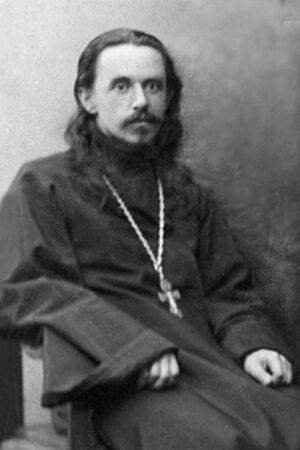

Two years later he became the abbot of the Monastery of the Savior (Holy Transfiguration) and St. Euthymius in Suzdal, but very soon the monastery was closed, and Fr. Leonty became a parish priest. He began to celebrate daily services according to the Typikon, serving ardently, with burning faith, illuminating everything around. People from all over the Diocese of Vladimir flocked to the parish—so great was the spiritual hunger among people in those hard times for the Orthodox Church. In 1924, Fr. Leonty was elevated to the rank of archimandrite.

The year 1929 was marked by a new phase of persecution of the Orthodox Church at the State level. On November 4, 1929 (the feast of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God), the Anti-Religious Commission adopted a resolution banning bell ringing.

The goal of the campaign was to close all the churches that by some miracle had survived in post-imperial Russia after the onslaught on Orthodoxy of the Renovationists and the robbing of the Orthodox Church through the program for confiscation of its property.

The confiscation of Church property

The confiscation of Church property

Meanwhile, the OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate) received a denunciation. Someone with the common surname Petrov wrote: “Archimandrite Stasevich used to be a member of the White-Tikhonites, but now he is a member of some particular group; many people usually gather at his church, especially nuns, and in general the Suzdal intellectuals; by his speeches in the church he undermines the authority of the Soviet Government. All the clergy... are White-Tikhonites. This group is often seen all together. We must expose it.”

The authorities did not even have to invent anything. Fr. Leonty himself gave them occasion to deal with him closely. “Bell ringing was banned,” Fr. Leonty himself later recalled. “I so wanted to glorify the Lord with ringing. I climbed up the bell-tower and rang vigorously for a long time. When I came down from the bell-tower, they met me with handcuffs.”

The criminal case was initiated on February 2, 1930, and on February 3, Fr. Leonty was arrested. It was the beginning of his spiritual labor of confession of the faith.

From the transcript of the interrogation of Fr. Leonty:

“I plead not guilty to the charges brought against me and explain that I have never belonged to any anti-Soviet groups and have not heard of such groups. I know all those taking part in the trial listed in the resolution, but I have not known them closely. I shy away from all acquaintances and live in isolation.”

Sentence: three years in labor camps. When he returned, he again served as a parish priest—this time in the Ivanovo region.

He was arrested for the second time on November 5, 1935. From the indictment (the spelling and punctuation of the original have been retained): “He was a member of the group of active church-goers of the ‘TOC’ (the True Orthodox Church)—and was its inspirer. He maintained ties with elements who feigned foolishness, and with Elder John of Ardatov, and presented the them as ‘visionaries’ and ‘saints’; he drew children of school and preschool age into religious activities by distributing various gifts among them; he spread provocative rumors about the end of the world, the coming of the antichrist and the fall of Soviet rule.”

Fr. Leonty was courageous and firm: “I plead not guilty to any of the charges brought against me.” The result: three years of labor camps. Karlag (the Karaganda Labor Camp in the Kazakh SSR). One of the most notorious Gulag camps with unbearable, inhumane conditions. This is what Fr. Leonty himself related: “We were often not allowed to sleep for whole nights. As soon as we lay down, they shouted: ‘Stand up! Fall in outside!’ It was cold and rainy outside. They would start tormenting us: ‘Lie down! Stand up! Lie down! Stand up!’ We would fall right into a puddle, into the mud. Then they would give the command ‘retreat’. We would come into the barracks, and once we started to get warm, they shouted again: ‘Stand up! Fall in!’ It went this way till the morning. And in the morning we had to go to hard labor... Once we’d had a meal in prison, they would take us out, line us up and say: ‘Now we’ll shoot you!’ They would aim at us, scaring us for a while and then drive us back into the barracks.’”

KarLag (the Karaganda Camp). Sentinel tower

KarLag (the Karaganda Camp). Sentinel tower

An incredible story happened with Fr. Leonty at that camp. What he was subjected to would have broken anyone. But the confessor of Christ not only endured it, he also taught his tormentors the lesson of standing in faith and Christ’s love for those who hate and offend you.

Do our readers know what a cesspool is? It is a pit in a latrine filled with all sorts of sewage. It was into such a pit that the camp guards let down the bound Fr. Leonty on a rope on Paschal night because he had refused to renounce the Lord. They then pulled him out and asked, “Do you renounce now?” “Christ is Risen!” was his answer. He was dipped into the filth again, then pulled out again and asked the same question. “Christ is risen, guys!” Fr. Leonty replied meekly. So they failed to make the confessor betray God. In the end they released him.

After the labor camp, Fr. Leonty returned to Suzdal. All churches were closed, so the archimandrite served in the apartments of his spiritual children who sheltered him. In 1947, Fr. Leonty was appointed rector of the Church of the Holy Trinity in the village of Vorontsovo of the Puchezh District [in the Ivanovo region.—Trans.]. Later he became the head of the local deanery. The pressure on the Orthodox Church in the late 1940s took on the form of the late 1920s: the authorities once again imposed excessive taxes on churches and closed them for non-payment. But Fr. Leonty managed to keep parish life alive, which attracted more and more people. A zealot of piety, he again served every day, and his services were almost monastic. All of this irritated the godless authorities greatly. They decided to arrest the archimandrite for the third time. As if sensing this, three days before his arrest Fr. Leonty distributed the icons and other belongings from his cell to his spiritual children. He was arrested on May 2, 1950, immediately after the Liturgy. The interrogations continued for three months nonstop. He behaved courageously, steadfastly, with great dignity, and at the same time meekness and humility.

From the interrogation protocols of the confessor:

“To the present time you have not given truthful evidence to the investigation about your criminal activities. Are you going to change your behavior and tell the truth during the investigation?”

“I will not change my testimony during the investigation because I did not commit any crimes against the existing political system in the USSR.”

“You are lying! The investigation knows that even in your sermons during church services, along with religious teachings, you spread provocative anti-Soviet fabrications.”

“During services and in conversations with believers I did not spread any provocative anti-Soviet rumors and I am not guilty of this.”

“What did you say about the so-called ‘Last Judgment’ and the ‘end of the world’?”

“I read the extract from the Gospel about the Last Judgment, but I did not myself interpret this passage from the Scriptures.”

“Now you have read the decision to bring you to criminal responsibility. Do you understand the essence of the charge?”

“The content of the charge is clear to me.”

“Do you plead guilty to the charge?”

“I plead not guilty to the charges against me. I have never been hostile to the Soviet Government and have never been engaged in anti-Soviet activities. I believe that I have served honestly in the Church, have never gathered anti-Soviet people around me and have not even met such people among my co-religionists.”

“You know that your criminal activity has been fully proven by the investigation. Are you going to speak honestly during the investigation?”

“I did not engage in criminal activity, and therefore I cannot change my testimony during the investigation.”

“But you were given testimonies that expose your ongoing anti-Soviet activities. You cannot refute these testimonies in any way and only deny your criminal actions without proof. You are once again invited to answer to the questions posed truthfully.”

“I have already said that the witnesses gave false testimony against me.”

“During past interrogations you concealed a number of your followers with whom you maintained close ties. Give us their names.”

“I did not have close ties with anyone.”

“During the last interrogation you showed that you were a supporter of the so-called true Orthodox faith. What is the essence of this faith?”

“For me a true Orthodox believer is someone who does not deviate from God’s Scriptures, is wholeheartedly devoted to the faith, and does not deform Church services. Personally, I try my best to celebrate full services, as it was done, for example, in pre-revolutionary monasteries. Services in churches should be celebrated daily, and I strictly adhered to this rule. I believe that a priest should be, first of all, a monastic, completely devoted to the faith, and therefore I have led a monastic lifestyle. I believe that the priests who do not hold services every day, shorten them and indulge in worldly temptations have apostatized from the Orthodox faith.”

Fr. Leonty was sentenced to ten years in the camps and sent to the Bratsk Labor Camp in the Irkutsk region. After Stalin’s death in 1953, an amnesty was issued, and Fr. Leonty’s case was reviewed. The seventy-one-year-old confessor was released on April 30, 1955. He wanted only one thing: to serve. On June 20, 1955, he was appointed rector of the Church of the Archangel Michael in the village of Mikhailovskoye of the Sereda District [the name of the Furmanov district between 1929 and 1963.—Trans.] of the Ivanovo Region. The parish was huge: it served the faithful of the district center (the local town) and twenty-four villages around it. The living conditions were deplorable—Fr. Leonty lived in an unheated hut. He visited those who needed pastoral care in their homes, for which he had to walk dozens of miles. And he served daily. Fr. Leonty only praised the Lord; not a word of complaint, not the slightest grumbling, not a single displeasure. The Lord endowed him with amazing humility and meekness. Just one example. The authorities were informed that the priest walked to the town, took orders for services and immediately performed them, whereas according to the law he was supposed to register them at the church. And so Fr. Leonty had to take orders in the town, walk six miles to the village to the church to register them, and then on the same day return on foot to the town and perform the services. It was an outright mockery of the elderly pastor. But Fr. Leonty fulfilled everything silently and meekly.

In 1960, Archimandrite Leonty was granted to celebrate the Divine Liturgy with the royal doors open until the Cherubic Hymn.

Archimandrite Leonty (Stasevich) It is sad that some clergy were personally responsible for the sorrows endured by Fr. Leonty. One of them wanted to be the rector of his church and scribbled anonymous letters; others slandered him for the sake of their own interests... Because of one of such denunciations the confessor was even banned from serving for a month. “I am crying and weeping,” he said. “But truth will come out. Everything will be revealed.” He was transferred to the backwoods—to the Church of the Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple in the village of Elkhovka of the Teykovo district. A miracle occurred there—through Fr. Leonty’s prayers a possessed woman was healed.

Archimandrite Leonty (Stasevich) It is sad that some clergy were personally responsible for the sorrows endured by Fr. Leonty. One of them wanted to be the rector of his church and scribbled anonymous letters; others slandered him for the sake of their own interests... Because of one of such denunciations the confessor was even banned from serving for a month. “I am crying and weeping,” he said. “But truth will come out. Everything will be revealed.” He was transferred to the backwoods—to the Church of the Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple in the village of Elkhovka of the Teykovo district. A miracle occurred there—through Fr. Leonty’s prayers a possessed woman was healed.

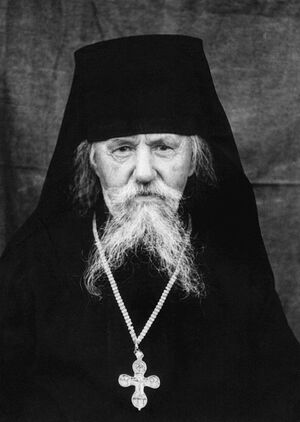

Meanwhile, the flock of the village of Mikhailovskoye petitioned for the return of their beloved pastor. Their hopes were eventually crowned with success, although Fr. Leonty was already eighty when he returned to the church of Mikhailovskoye. The Lord endowed him with the gift of clairvoyance. The confessor was a true spirit-bearing elder. He treated people with great love. He never denounced anyone, and was neither strict nor demanding. Gently and with great concern for the human soul he pointed to people’s spiritual illnesses and healed their spiritual wounds.

“Confessions with him were amazingly fruitful, very spiritual and very humble,” Archbishop Ambrose (Shchurov) of Ivanovo and Kineshma testified. “he never denounced you for your shortcomings, but tried to speak in such a way so as not to hurt you.”

One of Fr. Leonty’s spiritual daughters recounted, “He would give you a piece of paper with listed sins, and while you were reading these sins, he would point to some sin with his finger and say: ‘Read it again,’ which meant it was your sin. And when someone was very worried, Father Leonty would say: ‘I had it too.’”

His instructions were brief, and he gave them as if not from himself, but inspired by the Holy Spirit. He used to say to his close ones: “Paradise has been open to me for a long time, but I live for you, so that all of you may be saved.”

Many miracles occurred. Fr. Leonty would point to something, and further events confirmed the correctness of his words. And one day there was the following story. Early in the morning of April 16, 1970, Fr. Leonty performed a memorial service for the newly reposed Patriarch Alexei I. The people who were present at the service were shocked and stood in silence. After the service he was asked why he had celebrated a memorial service for the living Patriarch. Fr. Leonty replied: “His Holiness Patriarch Alexei has died, but last night I saw him and we prayed together for Metropolitan Pimen to be elected the next Patriarch.” Everything was confirmed very soon.

He prayed for everyone: not only for his spiritual children and parishioners, but even for blasphemers. A tractor driver wanted to destroy the bell-tower, about which he warned Fr. Leonty every day with cynicism and ridicule. As a result, while implementing his evil plan, he fell together with his tractor through the ice of the river on his way to the church, and died of a heart attack. Fr. Leonty prayed for him with tears. He answered his bewildered parishioners: “How can I not pray for him, if he comes to me every day, asking for prayers?”

Shortly before his repose the confessor began to choose a place for his own burial. He did not want to be buried behind the altar because “everything will be tarmacked over there.” He did not want to be interred at the small cemetery beside the church: “I don’t want tractors to drive over me.” Instead, he left orders that they bury him in a ordinary rural cemetery. Over time, the place behind the altar was tarmacked over, the small cemetery next to the church was plowed over and ridden over by tractors, but no one touched the village cemetery.

On February 7, 1972, Fr. Leonty celebrated his final Liturgy. The next day, very weak, he joyfully exclaimed: “We are coming to God, we are coming to God!” On February 9, the confessor took Communion, and the next day he peacefully fell asleep in the Lord.

Venerable Confessor Leonty Shortly before his repose, Fr. Leonty said to Fr. John, the second priest of the church in Mikhailovskoye, who was often rude to the confessor, “When I die, a lot of water will flow from me.” Fr. John scolded him for these words. And after batiushka’s death, he came to serve a Pannikhida at his grave and saw that a spring had gushed forth nearby. With tears he asked the confessor’s forgiveness: “Father Leonty, forgive me that I did not believe you.”

Venerable Confessor Leonty Shortly before his repose, Fr. Leonty said to Fr. John, the second priest of the church in Mikhailovskoye, who was often rude to the confessor, “When I die, a lot of water will flow from me.” Fr. John scolded him for these words. And after batiushka’s death, he came to serve a Pannikhida at his grave and saw that a spring had gushed forth nearby. With tears he asked the confessor’s forgiveness: “Father Leonty, forgive me that I did not believe you.”

Archimandrite Leonty (Stasevich) lived on this earth for eighty-eight years—meek and humble in heart, joyful and thankful to God for all things. In all the circumstances of his hard life he repeated only one thing: “I live in Paradise!” He was always with the Lord, wholeheartedly devoted to God. A model of strong faith and piety for the laity, of an austere God-pleasing life for monastics, and of a fiery ministry for priests. He was a visionary and a miracle-worker. The Lord did not spare him, sending him many trials. But the confessor always proclaimed: “Glory to God for all things!” And now at the Throne of God with all the saints our loving pastor, the Venerable Confessor Leonty, prays for us. He hears our prayers and helps us, sinners, as we run with faith and love to his grace-filled intercession.