Exactly five years ago today, one of modern Russia’s greatest elders stepped forever across the borderline between earth and heaven. It was clear to all those who knew him that even here on earth, he mysteriously, simultaneously abode in both the earthly heavenly realms. It is extraordinary and life-churning to be under the spiritual direction of such a man, especially if you are only just emerging from the darkness and falsehood of a sinful life, and the scales are only just cracking, I won’t even say falling, from your worldly eyes. This was how I could partially describe my own state when I first encountered Fr. Adrian. I can only attribute my immediate trust of him to an inner thirst for authenticity and probably the strenuous work of my newly-assigned guardian angel, recently received at holy baptism into Orthodoxy.

It happened like this: After Baptism, already speaking and understanding the Russian language, wild horses could not have dragged me away from Russia—a country that I had previously studied but which had now come alive to me in a completely different dimension—the dimension of Holy Russia with its deep roots in authentic, mystical, full to overflowing, yet extraordinarily practical and healing Christianity. So off I flew to what was still officially the Soviet Union. It was springtime on all levels: Holy Week, and Holy Russia reemerging from the militant atheist winter that had cast its frosty crust over that vast territory for seventy years. There was a freshness and naivete there that in some ways matched my own. A Russian immigrant in a ROCOR church had loaded me with various items of clothing and whatnot to bring to people in her homeland, and I was overjoyed to be able to take them. One of these items was destined to change my life. It was a pair of shoes for “batiushka”, with the address of this woman’s sister in Moscow.

“You should bring the shoes to him yourself,” Vera said to me irresistibly, her intensified gaze directed at me from under a lowered forehead in a poignant air of secretive urgency, when I met her at a church after a Bright Week service in the Russian capital. “I’ll take you there.”

On Friday evening in the second week after Pascha, Vera and I boarded a night train to Pechory in Pskov Oblast, near the Estonian border. In our cozy sleeping compartment, she filled me in on all that could be told at the time about “batiushka”, Fr. Adrian (Kirsanov); about how he was born to a deeply religious peasant family in a village near Kursk, how he fought in the Second World War, lived a life in the world between church services and disgusting workers’ dormitories, surrounded by drunken brawls as he silently prayed. After the war, he with difficulty freed himself from factory work and entered the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, where he was soon tonsured a monk and ordained a hieromonk. Spiritually very close to the great elder Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) and the now Archimandrite Iliy (Nosdrin), he led a deep and ascetic monastic life, penetrated through and through with holy, militant humility. I juxtapose these words because his humility was so deep that he was given the obedience of exorcising demons from demonaics. Such an obedience can only be relatively safely be carried out in deep and holy humility.

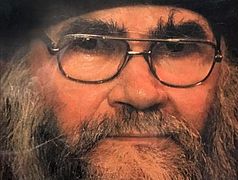

Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov).

Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov).

Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra.

Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra.

When demons are revealed for what they are they become enraged, and people who at their suggestion try to war against God become earthly expressions of this rage. And so, at the order of the Communist authorities Fr. Adrian was exiled from the Lavra to the Holy Dormition Pskov Caves Monastery in the town of Pechory. I supposed it was deemed easier to control this “unruly backward element” in a smaller monastery. That could also be why the holy elder, Fr. John (Krestiankin) and other very spiritual monks were literally concentrated there. But the result was an outpost of intense spiritual life and eldership far from the soviet capital. Fr. Adrian continued his exorcisms there, only now his “patients” were be able to settle in houses around the monastery, and confess to him, live under his close spiritual direction, and regularly attend divine services in this ancient monastery, which had never been closed even while all other Orthodox monasteries in Russia had.

Holy Dormition Pskov Caves Monastery. Photo: ppmon.ru

Holy Dormition Pskov Caves Monastery. Photo: ppmon.ru

We disembarked at the tiny train station in the deep dawn of Saturday and walked to the town. The air was filled with pleasant chimney smoke rising from the Baltic-style wooden houses against a gentle shimmering pink and violet layered sky—thrillingly typical of the Paschal firmament in Russia, when the sunrise comes earlier and earlier with the force of rapidly awakening life. We arrived at the Holy Dormition Cave Church just in time for the early Liturgy, which in keeping with his practice on every Saturday for many years, Fr. Adrian was celebrating. Vera arranged through Fr. Adrian’s close spiritual children a meeting after the service. It was still soviet times, albeit a thaw, so the meeting was appointed in a semi-conspiratorial manner. Fr. Adrian was given leave to bless the house of his spiritual daughters in the town, and it was there where I was to present him his shoes. He received them from my hands in a manner I had perhaps read about in a classic Russian novel—imbued with humble gratitude, sincerely making much more of the service than I or my worldly peers would ever have ascribed to it. With time I would only begin to understand how important this gratitude to other human beings is for a person’s relationship to God.

Soon, unobtrusively, with his gentle, loving smile, Fr. Adrian allowed the others to leave the room so that we could talk. In the course of this talk, with the deftness of an experienced doctor treating a gaping, festering wound, the elder made an initial treatment by hearing my lame confession, which he helped along by artfully revealing—as if about someone else—my main life sins. He blessed me to receive Holy Communion the next day—the Sunday of the Myrrh-Bearing Women.

To put it in medical terms, I had finally been directed to a specialist, and I knew that healing was here. I knew that I wanted to return, which I did within the year.

I won’t go on to relate all that happened after this—it’s too involved and personal. But I will say that it became very clear to me over the course of the roughly year and a half that I lived in a house next to this spiritual hospital, under the direction of this experienced spiritual surgeon, that spiritual awakening and growth is not about quickly reaching noetic prayer and becoming so spiritual yourself that you dare to teach others. No, it’s about humbling yourself till it hurts, giving up your own will in order to obtain bright, magnificent freedom. I am by no means saying that I progressed in this, but I at least saw the reality of it—a sight that is unforgettable. It is as a compass engraved in the soul, which one has the opportunity to refer back to. As it has been said, I am not holy, but I have seen holy men.

Jumping forward, as from a sort of Alpha to the Omega: At the end of this amazing year, in a stroke of final humbling, Fr. Adrian blessed me to enter the monastic life. He had been hinting at this all the time. For example, once I asked his blessing to invite him to a meal at his spiritual daughters’ house. He accepted, although he always seemed rather indifferent to foods, especially dainty foods. I tried my best to make a tasty soup, but it was as if I was doomed to failure. As he tasted it, he said, “no salt”—as if to say, there was no prayer put into it. In his gracious manner he thanked me for my love in creating this meal, but added, “What I really want from you is not a dinner (in Russian obed), but a vow (obet)—a play on words that referred to what we all understood as a monastic vow. I had stayed through the winter in Pechory without the outerwear necessary in that cold, damp climate, and he was always here and there giving me warm clothing—a down vest, a homespun wool sweater, wool socks. And they were always either black or dark brown. His other spiritual daughters just nodded knowingly: “That’s what he gives to future nuns.” He also let me know in no uncertain terms that it would be far from easy—through allegories, comparisons with other nuns, and by direct instruction. He said several times, “Don’t think that you will get any praise, or that you’ll just glide along.” (This is a loose translation—his words are hard to convey directly). “If you are truly laboring, the demons will war against you. If you find life easy, it means you are pleasing the demons.”

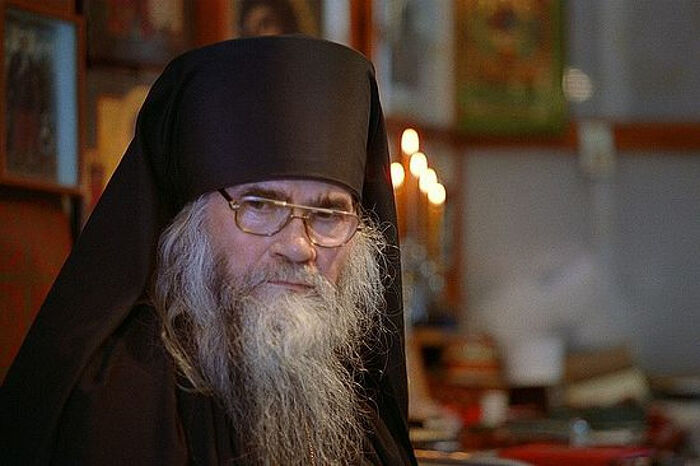

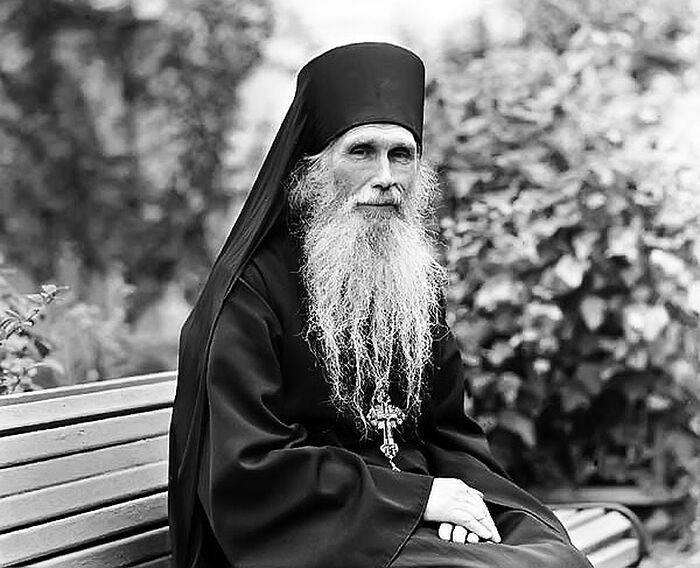

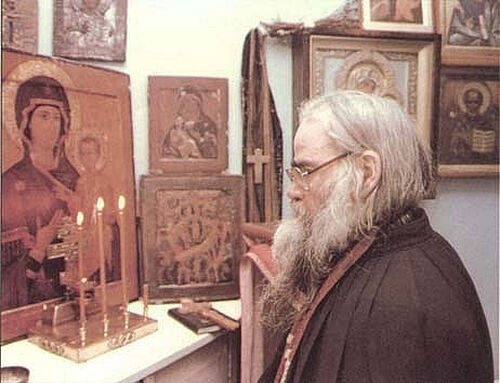

Archimandrite Adrian (Kirsanov)

Archimandrite Adrian (Kirsanov)

Anyway, he at length told me to leave Pechory, although I did not want to leave at all. For all the ten or so years that I did not see him, I nevertheless felt his prayers, getting me through difficult times. He never blessed me to return to him, for reasons known to him and Christ. Although, other people who knew him and me tried to get me to visit him before he reposed. Somehow, I couldn’t. I couldn’t act against his blessing. God’s ways are not ours. In his final months, he saw few people because he was extremely weak. But in his final weeks, he told one of his cell attendants—a very humble, kind spiritual daughter who had come to Pechory from the Ukraine—that very soon he would be perfectly well and would receive everyone who wished. This is exactly what soon happened—only not in the way she thought it would.

Soon he reposed in the Lord, and the news spread like wildfire. The hardships of travel were overcome by all who immediately dropped everything to attend the funeral service and burial. I and another nun living in Moscow, who was also his spiritual daughter and whom he had blessed to receive the monastic tonsure, travelled by car and stayed in the monastery guesthouse. Now I have to say that usually it is nigh unto impossible to make your way through a crowded church in the monastery during a big event. But when Mother Antonia and I entered the church, despite our initial despair at reaching the coffin, we were as if bounced like footballs in a zigzag across the packed church, coming to rest at the side of the coffin, where other nuns from convents he spiritually guided were standing.

We processed with the nuns behind the coffin to the courtyard before the holy caves, where the burial service continued. The caves are where all monks of the monastery are interred after death, with the elders having special spaces in the caves’ chapels. There were so many people in the courtyard that I doubted I would be able to enter the caves behind the elders’ coffin, to see it interred in the chapel wall. But somehow, after the long service, the nuns lined up in twos behind the monastery brothers as they processed around the courtyard and into the caves. I found myself at the tail of this procession. At the entrance, I looked queryingly at the monk standing by the door (he was supposed to close it after the nuns of the convents, because the caves are far too small to accommodate everyone), but he kept his head lowered in a sort of noncommittal yet encouraging gesture, at which I slipped in, and he deftly closed the door behind me. I was in heaven as I walked with the young nuns, clipping along almost militarily, singing, “Christ is Risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!” My singing fell in note-for-note in with theirs, and I felt as though these angelic beings were surrounding me with their dispassionate monastic kindness as we processed behind the holy remains of our beloved elder, who drew us along in a final act of blessing on his part, and obedience on ours.

Gratitude... I thank Fr. Adrian and the Lord with all my soul for those moments. They are what makes life joyous and full amidst all kinds of sorrows and difficulties. And on this Pascal day, I say with all my heart, “Fr. Adrian, Christ is Risen!”