He reposed in the Lord on March 10, 2023, at the age of 97. Fr. Iulian (Lazăr) was the spiritual father of the Romanian Prodromou Skete on Mt. Athos. He was the last of a generation of great spiritual fathers who grew up in the interwar period and became confessors of faith under the communist dictatorship. Several of them will soon be canonized.

Disciple of Elder Cleopa

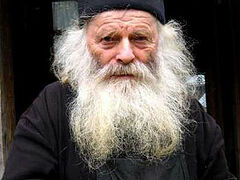

Fr. Iulian in 2018 Fr. Iulian (Lazăr) was on born on January 8, 1926, in the village of Vorona, Botoșani County. Romania had become “great” just eight years prior,1 and his generation grew up with a sense of pride of belonging to a country that had a bright future, much better than the past. It was this generation that laid the spiritual foundation of today’s Romania.

Fr. Iulian in 2018 Fr. Iulian (Lazăr) was on born on January 8, 1926, in the village of Vorona, Botoșani County. Romania had become “great” just eight years prior,1 and his generation grew up with a sense of pride of belonging to a country that had a bright future, much better than the past. It was this generation that laid the spiritual foundation of today’s Romania.

However, their bright dreams were carried away by the Second World War that descended on the country, tore it apart, and brought the red plague of communism. The dramas that played out then left a deep mark in the heart of the future spiritual father, and he began to seek solace in God:

Beholding the horrors of war, a friend and I decided to enter a monastery. The suffering made us children think about the monastery. So God prompted us to seek and choose the monastic life. It was a calling.

Archimandrite Cleopa (Ilie) At the age of twenty, the future spiritual father of Prodromou left the world to enter Sihăstria Monastery in Neamț County, where just two years prior, another Botoșanian, Fr. Cleopa (Ilie), was named abbot. And the monastery spiritual father was another schemamonk from Botoșani—the meek Elder Paisie (Olaru), under whose stole Fr. Iulian also confessed.

Archimandrite Cleopa (Ilie) At the age of twenty, the future spiritual father of Prodromou left the world to enter Sihăstria Monastery in Neamț County, where just two years prior, another Botoșanian, Fr. Cleopa (Ilie), was named abbot. And the monastery spiritual father was another schemamonk from Botoșani—the meek Elder Paisie (Olaru), under whose stole Fr. Iulian also confessed.

At the time when he became a new novice, Sihăstria was full of life. Although the skete didn’t have such a rich history like the great Secu and Neamț Lavras, but sanctified by the feats of the hesychasts who founded it, it attracted monks with its strict order and the fame of Elder Ioanichie (Moroi), one of the most famous ascetics of Neamț. Fr. Iulian didn’t manage to meet Fr. Ioanichie—the elder had died two years before he entered the monastery gates, but his name was surrounded by an aura of holiness. And Fr. Ioanichie left the cenobitic monks the power of his prayers and a humble abbot, his disciple, who used to take the monastery sheep out to pasture in the mountains, Fr. Cleopa (Ilie).

Hieroschemamonk Paisie (Olaru)

Hieroschemamonk Paisie (Olaru)

The white nights of beginners

A deep silence reigned in the monastery—the silence of the other world into which one plunges in order to find God. And in this silence of the night, Fr. Iulian was awake in prayer. His cellmate, Fr. Ioanichie (Bălan), with whom he shared not only joys and woes, but also prayer, was overtaken by sleep. Then he got up and humbly, with love for God, began to do prostrations and pray. They agreed that when one was resting, the other would get up and pray. Thus, in their cell, which they shared as brothers, prayer never stopped. And from his own cell, the abbot Fr. Cleopa would bless and strengthen them. And this severe struggle with the weak flesh and sleep sanctified them both.

Elder Iulian in the great schema But soon the thirst for God and prayer would be troubled by the red storm stirred up from the east. Decree No. 410, adopted in 1959, effectively abolished monasteries throughout the country, dispersing monks to their homes, into the world, where it was much easier to monitor and pressure them. In order not to be closed, Sihăstria was transformed in the eyes of the authorities into a shelter for elderly monks. Only the elderly monks and the young ones who had a theological education could stay.

Elder Iulian in the great schema But soon the thirst for God and prayer would be troubled by the red storm stirred up from the east. Decree No. 410, adopted in 1959, effectively abolished monasteries throughout the country, dispersing monks to their homes, into the world, where it was much easier to monitor and pressure them. In order not to be closed, Sihăstria was transformed in the eyes of the authorities into a shelter for elderly monks. Only the elderly monks and the young ones who had a theological education could stay.

The Securitate (Romanian Department of State Security) started searching for Fr. Cleopa, and he was forced to flee to the desolate dense forests to escape their claws. Left without the pillar of light that supported the monastery, Fr. Iulian also chose the eremitic life and retired to the desert together with another monk from the same brotherhood.

However, instead of weakening the monks, the years of communist persecution only made them stronger. Hidden in the light of God, these hesychast monks protected the country with their prayer. We don’t know the labors of Fr. Iulian as a hermit, but there is no doubt that the fruit was an even greater immersion into the depths of the heart and drawing near to Christ.

The relaxation that came in 1964 was needed for monastic life to return to normal. Only then could Fr. Cleopa return from the wilds of the forest. But he was no longer the same. He left a monk tried in the battle with the passions, full of strength, loved and revered, and returned a monk experienced in hesychastic trials, grown to full maturity in Christ, who would attract the entire country with his counsel and the light given him by grace. Fr. Iulian was spiritually baked in the fire of Fr. Cleopa’s instructions and cleansed in the tears poured out in Confession before Fr. Paisie (Olaru). He became a flame lit by two lamps.

A monk on the Holy Mountain

The Romanian Prodromou Skete, raised from the ruins

The Romanian Prodromou Skete, raised from the ruins

For any monk, Mt. Athos is a peak only not of stone but an invisible one, composed of prayers and tears and illuminated by the eternal love of the Mother of God. This is the Holy Mountain that the Most Holy One chose for herself and turned into her heavenly garden on earth. She summons her ministers here, and she also arranged that the communist regime would release the Romanian monks to Mt. Athos for a pilgrimage. Of course, the communists did this not out of piety, but to show the West, whose money they were eager to get their hands on, that they too were open for religious freedoms. Thus, Fr. Iulian and other monks from Romania were able to set foot on holy Athonite ground for the first time in 1977.

He was fifty years old and he was already an experienced spiritual father. He spent four years in Lacu Hermitage and then went to Prodromou Skete, which was in ruins at that time. “There had been no services in the church for more than thirty years! Rain was pouring down into the church and the plaster was falling from the walls. But we said that even were we to starve to death, we would never again return to communism,” said Fr. Atanasie (Floroiu), the current abbot of Prodromou, who came from Romania to Mt. Athos a year after Fr. Iulian. And Fr. Iulian never returned to Romania.

The depth of humility

Fr. Iulian at sixty-two years of age He had his own paths along which he quickly climbed to the summit of Mt. Athos to pray. In the evening I would see him leave; he disappeared instantly, even when he had passed eighty. At that age, he was strong as a rock, spiritually robust, with indestructible faith and iron health.

Fr. Iulian at sixty-two years of age He had his own paths along which he quickly climbed to the summit of Mt. Athos to pray. In the evening I would see him leave; he disappeared instantly, even when he had passed eighty. At that age, he was strong as a rock, spiritually robust, with indestructible faith and iron health.

Fr. Andrei (Coroian) was an indefatigable pilgrim. Like hundreds of thousands of Orthodox from the former communist countries, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, he began to take Athos by storm. For these pilgrims, longing for prayer and a life of holiness, it was a great joy to find the simple and humble love of Elder Iulian.

In the 2000s, when the Holy Mountain was flooded with Romanians, Russians, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Georgians who came on pilgrimage, Fr. Iulian was eighty years old. That’s when Fr. Andrei met him.

I’ve always felt at peace with him, so I became very close with him. Once, listening to his instructions, I sat in his cell all night, and at dawn we went to church together. I was amazed when I realized that he knew the entire New Testament by heart. In his cell he had a library of several hundred volumes concealed by a white curtain—a good library from which he was able to bring forth hundreds of quotes. And he had a special way of giving instructions, wrapping his counsel up in little poems to make it easier to remember.

He was a monk of holy life, a monk of colossal spiritual depth who had led a pure life from a young age. He reminded me of Fr. Sofian, a spiritual man of great power, who manifested himself in the depths of humility, love, and patience. He wasn’t a great preacher like Fr. Cleopa, nor a confessor of the faith like Fr. Iustin, but he was the personification of deep humility, which gave him great strength of faith. He was like a rock.

The gifts of holiness

Fr. Iulian with Fr. Cleopa on Mt. Athos in 1977

Fr. Iulian with Fr. Cleopa on Mt. Athos in 1977

Ascetic labors and prayers were formed in the heart of Fr. Iulian. His soul, strengthened by night vigils, gave strength to his body, as though it weren’t the body of an old man. In those years, he confessed thousands of Romanian pilgrims who flocked from all over the world to Mt. Athos. The door to his cell was always open. You could go see him at any time; monk or pilgrim—you were always welcome.

And that’s what Gheorge Crăsnean did one day in 2009. He knocked on the door and entered without waiting for the response. Fr. Iulian was sitting in the corner, his head bent over a Bessarabian who was confessing to him.

Father was listening to the confession, and tears were rolling down his face and flowing onto his stole, which was shaking from the sobs of this Christian from the other side of the Prut River! They were both weeping, and it occurred to me at that moment that God Himself might also be weeping from the bitterness of these repentant tears.

This gift of grace—to become one with the pain of the one confessing to you, and to build a bridge of boundless Divine love over the abyss of sins—is a sign of a Spirit-bearing confessor.

Fr. Constantine Coman recalls:

I had many meetings with Fr. Iulian, but one left a permanent mark in my heart. It was a general Confession. I’d done it before, but I’d never confessed in such detail before. I was staying on Mt. Athos with one hermit. I remember like it was yesterday… Fr. Iulian came to see us in this forest and heard my confession for hours, pouring his Divine goodness out upon me. This is a sign of a great confessor—kindness, a reflection of God’s kindness, which isn’t conditioned by our deeds. Such was Fr. Iulian… He won me over with his kindness, after I dumped out in front of him all my dirt all the way back to childhood. I think this confession in the forests of Mt. Athos has remained in my soul as one of the most beautiful pages of my Christian life.

Thousands of pilgrims who sought counsel from Elder Iulian also noticed something else from him: a gift of grace given only to the saints—the power to see with the eyes of the spirit. Often, it wasn’t even necessary to confess, because the Elder knew everything that was in your heart. Gheorge Crăsnean, who counted his trips to Mt. Athos (at sixty-three years of age, he’d already had 170 meetings with Fr. Iulian), witnessed how the Elder saw the pilgrims’ innermost thoughts several times:

Once I went to Mt. Athos with another man, and without knowing him, Fr. Iulian went up to him and said out of the blue: “You’re going to regret what you did. You’ll want to return but won’t be able to!” And he left, and this guy started weeping because he knew that everything Father told him was true. Thus the Spirit spoke through his mouth.

“His face radiated only light”

Costion Nicolescu met Fr. Iulian only once, but that was enough for the memory of the saint to be permanently imprinted in his soul:

Costion Nicolescu met Fr. Iulian only once, but that was enough for the memory of the saint to be permanently imprinted in his soul:

It’s been thirteen years already. When I first went to Prodromou, they told me the most experienced and capable confessor there was Fr. Iulian—that is, not the abbot Fr. Petroniu. Fr Iulian was considered a spiritual father with a capital S, and most of the monks were spiritually nourished under his mantle.

He received us in his cell. He was already elderly—eighty-three. He was very simple, small in stature; white-faced with a white beard—everything about him was white—smiling, and everything he said, he said with joy. He spoke with us and we jotted some of his thoughts. It was the counsel of a man who clearly had a wealth of experience behind him; a man who had achieved virtuosity in proclaiming the Gospel to whomever was before him—a skill that came through many years of honing, through prayer and ascetic labors. God became transparent through his being.

He comforted all of us; he had a sweetness of nature, a gentleness that called you to Confession. All of this was intertwined with steadfastness of faith, which I have seen in the great monks I’ve met. He was the kind of meekest father, ready to pour out all his warmth and love on you when he absolved you of your sins. You could feel him suffering with you in Confession. Even when he was talking about sins, he communicated to us with all the light of his being.

He had achieved the simplicity that is characteristic of our great confessors, who relied not on much study, but on the experience of faith. His simplicity was the simplicity of a peasant, and we had the impression that it was no longer him living, but Christ living in him, and this greatly transformed him. Therefore, his face radiated only light, but a light that was quite young. The old age peeking through the whiteness of his beard was paradoxically imbued with youth.

There was a fire in him that you can’t find even in young people—that unquenchable fire that is ever stoked, and not only by prayer, but also by something beyond prayer. Prayer comes from us, but Fr. Iulian had such a paradisaical state that had become natural for him—a state that didn’t come from him but was poured out on him from above. It seemed he had already left prayer and asceticism behind and had entered into another state—like a hot air balloon rising up to the heavens. Of course, the basket of his balloon was full of prayer and asceticism, but he was already ascending naturally, without their help.

I haven’t seen Fr. Iulian since then, but that unique encounter was so powerful that I have placed him forever upon the iconostasis of my heart.

Great transition

Fr. Iulian cutting the grass at Prodromou, 1988

Fr. Iulian cutting the grass at Prodromou, 1988

On March 9, Fr. Iulian closed his eyes. He didn’t die—the doctors said he was in a coma, but I’m sure he was in the hands of God. The next day, Friday, March 10, while the Divine Liturgy was being celebrated in the church, the fathers of Prodromou decided to serve Unction at the Elder’s bedside. At the fourth Gospel, Fr. Iulian opened his mouth, breathed three times, and departed to the Lord…

Gheorge Crăsnean’s last memory of his spiritual father is, in a way, the seal of the Elder’s life:

A few years ago, Father went through a difficult ordeal. He was on the verge of death. He didn’t recognize anyone anymore, but one of his disciples who knew the craft of natural healing returned him to us. A couple of weeks after this ordeal, he was able to walk around the garden again. I went to see him in his cell. We talked, and I said to him: “Father, it’s amazing: Two weeks ago you didn’t recognize me, and now you can quote Scripture by heart!” I saw that he was sad, and he said to me: “What, do you still not understand that now, while we’re talking, the Holy Spirit is with us?”

Therefore, I confess to you that I even have a kind of joy that Father has died, because he who lives well can’t die badly, and he was a monk who really lived well. And I’m sure that he’s in Paradise, because he was a man of holy life.