Certain philosophers of antiquity are sometimes referred to as “Christians before Christ”, and there are reasons for this.

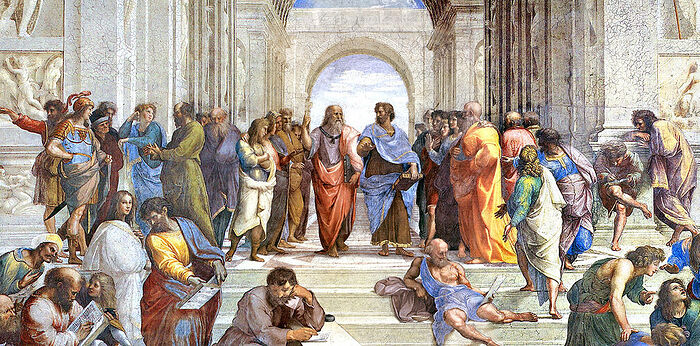

Raphael. School of Athens (1509-11) Fresco. Photo: wikimedia.org

Raphael. School of Athens (1509-11) Fresco. Photo: wikimedia.org

There are many opinions on this subject, but it seems to me that the main prerequisite for the formation of such a view was the fact that many ancient philosophers gradually, by reasoning, came to a doctrine of a Single Beginning or the basis of the world. For example, it can be the monad, which the Pythagoreans understood as the indivisible element of being, the origin of the number, while the number itself was considered to be a condition for any knowledge. Anaximander introduced the concept of “apeiron”—an infinite and boundless primordial substance, which is the basis of the world. For Plato, “the One” is a super-existential prerequisite for any existence, without which everything would turn into chaos and, ultimately, into non-existence. Many more examples can be cited, but you cannot ignore the fact that it was the doctrine of “the One”, regardless of the content, that led to the fact that, having discovered the Jewish faith in the One God, some pagans even before the Birth of Christ accepted Judaism, becoming co-heirs, and sometimes full heirs with Israel.

Thus, we can say that ancient philosophy played a positive and even salvific role for individual people. We also know that practically all those whom we call the Church Fathers had excellent educations, which at that time included the knowledge of philosophy, mathematics, harmony, rhetoric, astronomy and so on. It is also no secret that many of the terms that we use today in Christian theology were borrowed from philosophy and then rethought from the point of view of the Gospel truths. Let’s look at some of them and see how Christianity gave new content to the “old” pagan wisdom.

Perhaps one of the smallest differences is in the concept of the “soul”. Ancient philosophers believed that the soul gives life to the body. The doctrine of the soul as an immortal entity responsible for the thinking and morality of a person appeared as well. Many holy fathers said approximately the same. We know that the soul is an integral part of human nature, which was created by God. However, it is impossible to speak about the soul without mentioning the body. In this regard, antiquity is characterized by dualism. In Plato’s philosophy, the body is the soul’s tomb and prison, the deliverance from which was perceived as a blessing. Therefore, the soul was regarded as the good, and the body as the evil principle in a person. The Christian perspective on the body is absolutely different. All of God’s creation is very good (Gen. 1:31), therefore ancient dualism is alien to Christianity here. Moreover, the Word became incarnate, including in the human body. The Savior was Resurrected in the body, thereby making the Resurrection available to everyone.

Now it is logical to talk about the perception of man in general. In addition to the mentioned view of Plato, we can also consider Aristotle’s opinion. According to him, man is part of a harmonious and orderly cosmos. In addition to the “vegetative” component, man can think and speak, thanks to which such abstract concepts as goodness, justice, good, etc. are available to him. Aristotle also called man a “political animal” in the sense that he can only be a human being when he lives among people like him. Since the time of the Old Testament, the Jews perceived man as the crown of God’s Creation, His image. Christianity opens for man the possibility of apotheosis—that is, unlike ancient philosophy, where the position of man in the cosmos was unchanged, with the Coming of the Savior and thanks to His redemptive accomplishment everyone has a chance to enter into the closest communion with God, and to be transformed.

The concept of virtue is inextricably linked with human activity. Justice was often considered to be the highest virtue in ancient philosophy, but you still need to grow up to it. For Plato there were three parts to the soul (we can often see the same in Christian asceticism): the rational, the spirited, and the appetite. The first corresponds to such virtues as prudence or wisdom; the second to courage; the third to moderation or abstinence. The attainment of all these virtues leads a person to justice. For Aristotle, virtue is the ability to find the “golden mean” in everything, avoiding both excess and deficiency simultaneously. For antiquity, virtue is a moral category, while for Christianity it is a spiritual category. Christians strive to become like Christ, in Whom all the virtues are manifested to the utmost. In Christianity a person does not strive for good for the sake of profit, but for attaining life in God; therefore virtue also becomes a theological category.

Now let’s talk about love. In antiquity, love was one of the principles of cosmic interconnection, a feeling caused by a thirst for wholeness and providing completeness and unity. In the Greek language several terms were developed that distinguish between the types of love: “eros”—passionate and sensual love; “philia”—affectionate love that involves friendship; “agape”—merciful and sacrificial love; “storge”—familial love. For Christians, love is one of the key concepts that define the relationship between people and God. In Christianity, love has many meanings. Through love for God a Christian loves everything He created, and vice versa—through love for God’s Creation, for man, a Christian learns to love God too. The words of Christ about love for enemies in the Sermon on the Mount (cf. Mt. 5:44) could not even have been imagined in ancient thought.

Let’s talk about freedom. On the one hand, in ancient philosophy, freedom was at best understood as self-control. It is on self-control that self-identification was based for the Ancient Greeks. On the other hand, the Stoics were determinists. They argued that man was subject to nature and fate, that he was not free at all. At the same time, the goal of a Stoic’s life was to attain a state of passionlessness, indifferent dispassion, thanks to which he could understand everything that was happening around him. A passionless person is subject only to reason. In Christianity, freedom is not just one of the key concepts, but one of the understandings of the image of God in man. Thanks to freedom, he can determine his existence, his position in the world and bear full responsibility for his choice. Now man’s lack of freedom is manifested in his inability not to sin, therefore the return to freedom that he lost is deliverance from sin through likeness to Christ.

Looking at the interconnections considered above (and they are not limited to the listed examples), you begin to appreciate much more the treasure that each one of us finds in the Church. Philosophy is worth studying if only because with the right approach you can derive benefits from it not only for your own life, but also to develop the ability to defend Christian truths. If the Church Fathers did not disdain philosophy, then all the more should neither we ignore it—of course, without forgetting the Holy Scriptures.