How diverse can the life of a man be? A pie vendor at the market, the owner of the largest sausage factory in Russia, a supplier to the Court of His Imperial Majesty, a penniless old man in a tumble-down house on the outskirts of a settlement deep in the woods... And then also a philanthropist remembered for generations, even in Soviet times, despite the propaganda about “bloodsucking exploiters,” the builder of a beautiful church and... a holy martyr. All this is the description of the man, a merchant of the second guild, Nikolai Grigoryevich Grigoriev.

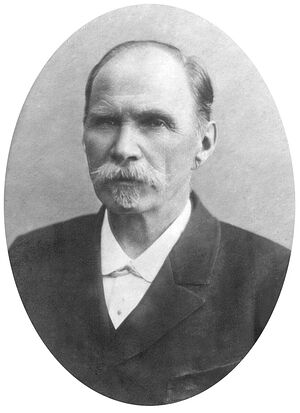

Nikolai Grigoryevich Grigoriev Nikolai Grigoriev was born in the village of Ratmanovo, Uglich uyezd, Yaroslavl region, on December 1, 1845. There were pictures of peasant labor preserved in his childhood memories, but also his whole family’s visits to the church in the village of Dubrovy, a parish church for the residents of Ratmanovo. They had to travel twelve versts through forests and swamps. Some time later, the parishes were reorganized and Ratmanovo was attached to Sergiyevsky. It wasn’t that far, about five versts away, but the old wooden church of St. Paraskeva of Iconium was old and dilapidated. It only had services in winter, while in summer the worshipers were welcomed by the unheated St. Sergius Church made of stone. According to tradition, St. Sergius of Radonezh, the luminary of Russian holiness, visited Sergievsky and founded a monastery there. Sergievsky hermitage existed until the thirteenth century. During the secularization of the Church under Catherine II it was closed, but its church continued to operate, warming the hearts of residents of nearby villages with prayer.

Nikolai Grigoryevich Grigoriev Nikolai Grigoriev was born in the village of Ratmanovo, Uglich uyezd, Yaroslavl region, on December 1, 1845. There were pictures of peasant labor preserved in his childhood memories, but also his whole family’s visits to the church in the village of Dubrovy, a parish church for the residents of Ratmanovo. They had to travel twelve versts through forests and swamps. Some time later, the parishes were reorganized and Ratmanovo was attached to Sergiyevsky. It wasn’t that far, about five versts away, but the old wooden church of St. Paraskeva of Iconium was old and dilapidated. It only had services in winter, while in summer the worshipers were welcomed by the unheated St. Sergius Church made of stone. According to tradition, St. Sergius of Radonezh, the luminary of Russian holiness, visited Sergievsky and founded a monastery there. Sergievsky hermitage existed until the thirteenth century. During the secularization of the Church under Catherine II it was closed, but its church continued to operate, warming the hearts of residents of nearby villages with prayer.

Peasant childhood is short. Aged ten, the boy was considered quite capable of a full workload. Kolya’s father worked in the field in the summer, and in the winter he traveled to Uglich for seasonal work in a small sausage factory, or as it was called then, a sausage house. In 1855, he took his son with him. The inhabitants of Uglich were often called sausage makers at the time, as the best sausage producers operated in this ancient town from as early as Petrine times. They were artisans and did everything by hand. The ten-year-old Kolya Grigoriev began his work life at one of them. The boy happened to be quite deft and thirsty for knowledge. Not only did he work well, but he also took an interest in production technology and by the age of a little over fifteen, he had already had learned its secrets. As for his life’s journey, it took him to new places, this time to the first capital of the nation.

Nikolai did not succumb to the corrupting influence of a big city: he did not get to drink or waste money, but he put aside every penny

The year 1861 was notable in Russian history because of the abolition of serfdom. The centuries-old foundations were breaking apart. Both land owners and peasants found themselves at a crossroads—how to live on. Young Nikolai kept his wits. He fixed his passport and traveled to Moscow. Once there, the young man did not spend much time looking for a decent position and went to work where help was needed. He became a pie vendor on Okhotny Ryad Street. The position was among the lowest, but it gave both bread and shelter. Some time later, the sensible young man was noticed by the owner of one of Moscow’s food shops and invited to work for him, this time as a clerk. Kolya agreed, of course.

As he was working in the shop, he mastered the basics of commerce, just as he had previously mastered the basics of sausage production. He did not succumb to the corrupting influence of the city—he did not drink or wast money but saved every penny. Sooner or later, he managed to open his own sausage house on Okhotny Ryad. By then, Nikolai was already married to Anna Theophanovna, the daughter of his first employer. The owner himself, his young wife and a few hired help made up the first Grigoriev production team. They worked with honesty and alacrity and their sausages came out quite delicious. The enterprise was making a profit. Nikolai Grigorievich turned out to be a talented technologist and entrepreneur. By 1876 he had become a merchant of the second guild, and in 1878, having accumulated the initial capital, he bought out the premises of F. Volnukhin’s sausage factory in Kadashevskaya Sloboda, nonoperational by then.

Tea time at the dacha. Nikolai Grigorievich and Anna Theophanovna

Tea time at the dacha. Nikolai Grigorievich and Anna Theophanovna

The young industrialist handled the matter of purchasing shop equipment on a grand scale. Within twenty years, he replaced the ruins with the most modern sausage plant in Moscow. He brought the best equipment from abroad, right down to his own mini-electric power station. Ten two-story stone buildings, a huge meat-safe for storing ten thousand pood (one pood equals to sixteen kilograms. —Trans.) of meat, and electrical equipment. He even installed outdoor lighting and rails with carriages running between the buildings—nothing like this had ever been seen in Moscow before, at least not in the sausage-making industry! N.G. Grigoriev’s sausage and food products factory became the largest production of meat delicacies in Moscow, if not in the whole of Russia. It produced up to a hundred thousand poods of sausages in eleven varieties. Additionally, there were two hundred thousand pieces of pork hams, smoked and boiled ham, roll-ups, and boiled Vienna and Russian sausages, and then stuffed geese, ducks, turkeys, capons, and poulard... Just reading the list makes your mouth water! The Grigoriev’s factory had a store where this finger-licking goodness was sold at discounted prices not only to workers, but also to the residents of the neighboring area. In total, Moscow had six large Grigorievsky stores and several small ones. Its products were delivered to different cities of Russia as far as Siberia, as well as abroad to Paris, Berlin, and Vienna. It was awarded ten medals at international exhibitions. Grigoriev’s sausages were welcomed at the palatial tables of the tsars, and from 1896, the factory received the honorary title of the Supplier of the Court of His Imperial Majesty, while its owner was named a hereditary honorary citizen. One significant detail: in 1896, during the infamous celebrations of the coronation on Khodynka Field,1 the gift sets for common folk included, among others, two hundred grams of Grigoriev’s sausages.

While making his way in life, Nikolai Grigorievich preserved a humane attitude

While making his way in life, Nikolai Grigorievich preserved a humane attitude. Out of care for his workers, he repurchased nine residential houses in the First and Second Kadashevsky Lanes and at Bolshaya Ordynka adjacent to the factory. Workers with families were offered free housing there, with a dormitory for unmarred men on the territory of the factory. Factory workers, numbering about two hundred, and a hundred employees had their own firstaid clinic, school, kindergarten, and free canteen. What’s noteworthy is that the backbone of the factory staff was made up people from Nikolai Grigoriev’s native land, Ratmanovo and neighboring villages. He sincerely considered his fellow villagers as relatives and thus offered them both work and shelter. Nikolai Grigorievich himself and his family settled in a large house in Second Kadashevsky Lane. One of its entrances faced the courtyard of the factory, so that it took no time for the owner and his sons, who studied the basics of business from childhood, to show up at the shop floor. When the First World War broke out, Nikolai Grigorievich made room for the military hospital in his residence. This was the scale of his values: family, work, and Motherland... Naturally, it simply could not be otherwise.

Grigoriev’s family home in Moscow

Grigoriev’s family home in Moscow

The factory became for Nikolai Grigorievich an extension of his own family home. It was truly a big family with the founding father at its head. A simple Russian man, he achieved everything by working hard and brought the ideal of true brotherhood to fruition. He created the very same corporate culture that modern large companies are so concerned about, but more often than not, it is nothing but hypocrisy. The secret of success here lies in the genuine, good-hearted attitude towards others, when you see them as equals and not simply instruments for making money. Looking at the photos of Nikolai Grigorievich, you realize that this man was completely devoid of arrogance and the desire to flaunt his success. Modest and approachable, he even dressed simply and never displayed any of the ostentation of the “nouveau riche” or vaunted himself over the ones he once broke bread with.

His fellow countryman could come to him for help and no one left without being comforted. There are still some folks living in Ratmanovo whose great-grandmothers, brides from poor families, were gifted a dowry by Nikolai Grigorievich. This help was quite significant: it was hard for an unendowed bride to marry someone, and even after becoming someone’s wife she might have to endure reproaches and rebukes all her life. The gratitude of the girls who received help was such that the memory of it was passed down from generation to generation. For feasts such as Christmas, wagon trains loaded with gifts travelled from the successful countryman to Ratmanovo, obviously carrying mouthwatering products from his factory. Nikolai Grigorievich also built and maintained a paramedic station with a maternity ward in his native village that treated about six thousand patients.

There are textbook examples of people losing touch with their roots, faith, and kindness once they gain success. But could it also be true that our textbooks examples, compiled when it was customary to see only the dark side of historical Russia, have been all very wrong? Meanwhile, many Russian merchants who were born as peasants preserved the best qualities inherent to this most traditional of classes: deep faith in God, love and respect for the Motherland and its people, regardless of their position and wealth. As a tribute to those merchants, Russia still have some of the churches, hospitals, and factories they have built...

Nikolai Grigorievich also preserved deep faith. He became the main benefactor of the Church of the Resurrection of Christ in Kadashahy, the parish church of his household and factory. During the general repairs in the church that took place in 1893–1903, he repaired its porch stairs, lined the floors with cast-iron slabs, and donated expensive liturgical utensils.

The restored church of the Holy Hierarch Nicholas the Wonderworker in Sergievsky

The restored church of the Holy Hierarch Nicholas the Wonderworker in Sergievsky

In addition to the Church of the Resurrection in Kadashy, Nikolai Grigorievich also helped several other churches, including the Church of the Apostles Peter and Paul in Petrovsko-Razumovsky not far from his summer house. He was elected its steward. It’s worth noting that in pre-revolutionary Russia, the church steward wasn’t the parish council vice-chair as is customary today, but someone who actually took care of the material needs of the church. That’s exactly who the merchant Nikolai Grigorievich was.

To build a church in the place of his birth was a dream Nikolai Grigorievich cherished from his youth

However, his major good deed was the construction of the St. Nicholas Church in the village of Sergievskoye near Ratmanovo, completed before 1911. To build a church near his place of birth was a dream Nikolai Grigorievich cherished from his youth. The Church hierarchy blessed him to build it in Sergievskoye, that ancient place of prayer. The result was a beautiful white stone church in the style of Russian fretwork, with a heap of kokoshniks,2 tent-shaped top, and five onion domes. Nikolai Grigorievich dedicated its construction to the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of his factory. “Not to us, O Lord, not to us, but to Your name be the glory,” the Russian merchant never grew tired of thanking the Creator for his achievements!

The heated church was designed to accommodate six hundred people. In the fall of 1911, it was consecrated by Archbishop Tikhon (Belavin) of Yaroslavl—the future holy Patriarch. Local residents were jubilant and thanked the church builder—yet, no one then knew that a short time later Nikolai Grigorievich would be faulted for the construction of the church, “a hotbed of toxic religious propaganda”...

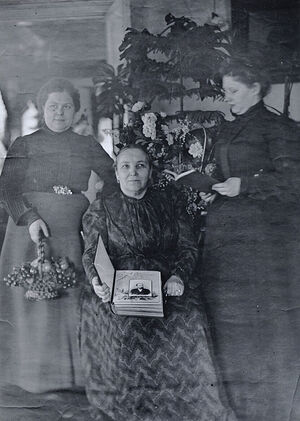

Anna Theophanovna with daughters-in-law But at the time, Nikolai Grigorievich did not stop at the construction of the church. He undertook to arrange a convenient road leading towards it between Ratmanovo and Sergievsky. It is worth noting that for its construction, he purchased the stones from the local peasants who had collected them on their plots. This was a double good deed: the locals were basically paid for clearing their own fields. The benefactor undertook to plant trees along the road so that travelers walking along it on hot days wouldn’t be exhausted from the heat. That’s how he lovingly took care of every detail of the construction. But sadly, the First World War prevented the realization of the project.

Anna Theophanovna with daughters-in-law But at the time, Nikolai Grigorievich did not stop at the construction of the church. He undertook to arrange a convenient road leading towards it between Ratmanovo and Sergievsky. It is worth noting that for its construction, he purchased the stones from the local peasants who had collected them on their plots. This was a double good deed: the locals were basically paid for clearing their own fields. The benefactor undertook to plant trees along the road so that travelers walking along it on hot days wouldn’t be exhausted from the heat. That’s how he lovingly took care of every detail of the construction. But sadly, the First World War prevented the realization of the project.

Meanwhile, life moved forward. Old age was drawing near, and it seemed to herald nothing but well-deserved honor and peace. His children were all grown up: two sons and two daughters. Konstantin and Michael continued their father’s legacy. Beginning from the age of fourteen, they helped at the factory, having worked all the positions from the lowest to the top. The daughters were married and grandchildren were growing older. There are photos left of a large family vacationing at the dacha in Petrovsko-Razumovsky. Contentment, mutual love, and peace. But then came the day when all that was crushed.

The revolution happened in Russia. Apparently, Nikolai Grigorievich did not immediately realize the scale of the catastrophe. After all, the workers loved him and his production was of benefit. Yet... the wave of destruction couldn’t care less about what exactly got in its path. The ideologists of the revolution condemned to destruction all “class alien elements,” where the good ones were considered even more harmful than the “bad” ones, because they would hinder the spread of the very idea of world revolution. In 1918, the factory was confiscated and closed. Konstantin and Mikhail Grigoriev were arrested and sent to Butyrka prison. All property was confiscated. Anna Theophanovna, Nikolai Grigorievich’s faithful wife, unable to endure what happened, died of grief.

Grandchildren of N.Grigoriev play croquet at dacha in Petrovsko-Razumovsky

Grandchildren of N.Grigoriev play croquet at dacha in Petrovsko-Razumovsky

The authorities did not kill Nikolai Grigorievich, who by then was already seventy-five years old. They were probably afraid that it would turn the numerous workers of the Grigoriev factory against them. But the fate prepared for him was even harder than quick death. In 1919, he was deported to his native village and deprived of civil rights. The locals were strictly forbidden to accept the exile into their homes or help him in any way. He was practically condemned to die of hunger and cold. His native home in Ratmanovo was occupied by strangers. A lonely elderly man settled in an abandoned bathhouse on the outskirts of the village of Derevenki near Sergievsky. Сompassionate villagers certainly tried to bring him food and firewood. But the authorities didn’t shirk checking the fulfillment of their restrictive measures. They put up a sentry of ideologically loyal Komsomol members who caught violators by the bathhouse. Nikolai Grigorievich, barefoot and dressed in rags, had to beg from door to door through the villages and find sustenance in the woods. He this way for a good three years. Did God comfort him? Was He with His sufferer? We will never know that, but we believe that, yes. Finally, his way of the cross came to an end. In the fall of 1923, local hunters found the body of Nikolai Grigorievich in the woods. Judging by the place where it happened, the martyr was walking towards the church he had built, the St. Nicholas Church that stood shut for a year already at the orders of the new “masters of life”. He was buried nearby in secrecy in disregard of the threat of persecution. A cross made of bricks was laid out on the grave. That’s how Archimandrite Victor (Zakharov) recognized it when he was given obedience to restore St. Nicholas Church at the end of twentieth century and became interested in its history. Owing to his efforts and with the blessing of Archbishop Mikhey of Yaroslavl and Rostov, Nikolai Grigorievich was glorified among the locally commemorated saints as a martyr who suffered in large part for the faith, as he meekly bore to the end the heavy cross he was vouchsafed to bear.

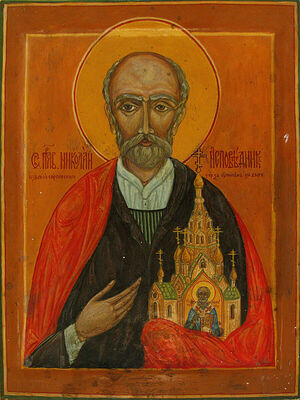

The icon of the new martyr Nikolai Grigoriev One can only be stunned by this narrative. It undercuts the stereotypes about greedy merchants, along with the modern stereotype that says “nothing personal, it’s only business,” which means one supposedly can’t succeed otherwise. It also speaks about how terribly savage the people can be. What was in the souls of those young Komsomol members who didn’t let anyone bring bread to an old man dying of hunger? To whom were they more inhumane—to Nikolai Grigorievich himself or to his neighbors who had to live knowing that a man who had done them so much good was suffering nearby? He was sentenced to starvation, but they were condemned to the murder of the soul, to indifference and faithlessness... But the martyr was glorified with God, while faith and gratitude in the hearts of people was restored—or it could be that it really never died.

The icon of the new martyr Nikolai Grigoriev One can only be stunned by this narrative. It undercuts the stereotypes about greedy merchants, along with the modern stereotype that says “nothing personal, it’s only business,” which means one supposedly can’t succeed otherwise. It also speaks about how terribly savage the people can be. What was in the souls of those young Komsomol members who didn’t let anyone bring bread to an old man dying of hunger? To whom were they more inhumane—to Nikolai Grigorievich himself or to his neighbors who had to live knowing that a man who had done them so much good was suffering nearby? He was sentenced to starvation, but they were condemned to the murder of the soul, to indifference and faithlessness... But the martyr was glorified with God, while faith and gratitude in the hearts of people was restored—or it could be that it really never died.

I heard this story as I was watching a movie about Nikolai Grigorievich Grigoriev called “Merchant of Zamoskvorechye. Light from the heart. Nikolai Grigorievich Grigoriev” made by director Elina Baklashova. It is part of the documentary series, with each series revealing a forgotten gem—the name and the fate of a Russian merchant, philanthropist, creator. To watch the movie “Merchant of Zamoskvorechye. Light from the heart. Nikolai Grigorievich Grigoriev” and other films of the series, go to Elina Baklashova’s website [Russian].