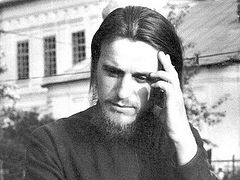

Protopriest Maxim Ivanov. Photo: Pravoslavie.ru

Protopriest Maxim Ivanov. Photo: Pravoslavie.ru

Young, Smiling, Too Active

When I first saw Father Maxim, I asked if he was related to Hieromonk Vladimir (Shikin), the tireless laborer of the St. Seraphim-Diveyevo Monastery—the resemblance was too obvious. To this, Father Maxim replied: “No, no relation.” Later it turned out that I was not the only one who thought so. In particular, one of the parishioners, describing him, said: “You will recognize Father Maxim right away; he is the spitting image of the monk from Diveyevo that everyone writes about.”

Father Maxim practically flew around, glowing with happiness; he was everywhere at once, talking to everyone…

Father Maxim came to the Ascension-St. George Church, located in the old part of Tyumen, young, smiling, and too active. Father Maxim practically flew around, glowing with happiness; he was everywhere at once, talking to everyone. Restoration work was in full swing there; the floor was not laid everywhere, the ceiling was only in the center, but still there was a feeling of something accomplished. The history of the church, alas, is in many ways typical for our country: it was built in the eighteenth century, closed in 1929, the building was used as a club for leatherworkers and chemists, then transferred to a sheepskin-fur factory. And, judging by the sharp smell that lingered in it for a long time after its return to the Church, apparently, not only sheepskins were stored in the holy place, but also fuels and lubricants. Remarkably, there were always people who gladly cleaned, whitewashed, and plastered in the church. My first church obediences were connected precisely with the Ascension-St. George Church. And on October 21, 2006, the honorable relics of the enlightener of Siberia, Metropolitan Philotheus (Leshchinsky), long considered lost, were found in a hiding place. When they were transferred in a solemn procession to the Holy Trinity Men's Monastery, there were so many people that the cable-stayed pedestrian bridge over the Tura River literally shook.

Speaking of this church, one cannot ignore another shrine—the icon of John of Tobolsk. It—or rather, what was left of it—was returned in the early 2000s from the Kurgan region, where in that same 1929 it was taken along with others and laid on... the cattle yard. The icon lay face up, and people and cows walked over it daily... Decades later, only a board with an inscription on the reverse side remained of the icon. It was cleaned, washed, returned to its former place, and it began to renew itself. At first vague outlines, then the face, and after that the eyes and chin gradually began to appear.

Father Maxim entered this all-encompassing poverty with his young Matushka Julia. They settled in a little house on the church grounds, seemingly from the century before last, which is very hard to call comfortable, although there seemed to be plumbing there.

Immediately the church became crowded, or more accurately—full of families with many children. Weddings, baptisms, and molebens before the newly found icon of John of Tobolsk became constant. “The young priest could easily travel to the ends of the earth for confession, a funeral, or the consecration of an apartment or dacha.” And in communication he was always simple and accessible.

Children enjoyed his special love and favor. As I remember now, in the depths of the church several layers of carpets were laid so that the little parishioners who decided to sit or take a nap would not catch cold, and nearby in the corner stood something like a changing table.

The Baptism of Rozaliya

Once I asked Father Maxim to go and baptize my good acquaintance, a wonderful person, a doctor with a capital D—Rozaliya Iosifovna Dombrovskaya. The situation was, let's say, not simple: Rozaliya Iosifovna was born a Lutheran, but at the age of over seventy she began to persistently express a desire to accept Orthodoxy, and at the same time she wanted to see me as her godmother. I will note right away that there is no merit of mine in this. By her essence she had long been, and perhaps always was, Orthodox.

Once I asked Father Maxim to go and baptize my good acquaintance, a wonderful person, a doctor with a capital D—Rozaliya Iosifovna Dombrovskaya. The situation was, let's say, not simple: Rozaliya Iosifovna was born a Lutheran, but at the age of over seventy she began to persistently express a desire to accept Orthodoxy, and at the same time she wanted to see me as her godmother. I will note right away that there is no merit of mine in this. By her essence she had long been, and perhaps always was, Orthodox.

Here are just a few highlights from her life story. After graduating from medical school, she began working in the department for premature babies, while managing to combine work with studies at the medical institute. She talked about how right after classes she went on night duty, which in principle was convenient, because she loved both work and study immensely, and therefore did not know what fatigue was. She looked at the tiny babies who came into this world before term, and all the time thought about how to help them. Mortality at that time (the nineteen-seventies) was quite high. And she came up with an idea: She began to respond to every signal from the child. Eyes opened—run to feed from a pipette, if only two or three drops, but necessarily so that the baby felt the taste of food. If he stirred—approach, let him know you are nearby. Many leave the babies in the incubator, thinking that is enough, but it is not. The little person feels whether he is safe or not, no matter what people say. She talked to the little ones for a long time, read poems to them, prayed and sang songs. Little by little the babies began to recover to the joy of their mothers. Gradually mortality dropped to zero, doctors began to receive thanks, and the young midwife Rosa was even given a bonus—fifteen rubles.

After graduating from the medical institute, as a gynecologist she was sent to a district hospital, and there she had to face what she had studied in her beloved institute but had never encountered in life—“termination of pregnancy.” Abortion in Soviet medicine was put on tap; in every hospital three days a week were abortion days. No more than twenty minutes per operation, including anesthesia.

She fell at the feet of the chief doctor and said:

“I want to retrain in any other specialty. I love medicine, what am I saying—I adore it, but I cannot perform abortions.”

The boss looked at the plan and dryly informed:

“There is a cosmetologist position, and we will allocate a room for you, and you don't need to study much—only six months in Moscow. Write an application; tomorrow I will issue the order.”

She wrote it. And then she asks:

“And what is cosmetology?”

“You will learn and tell us,” came the answer.

In the nineteen-eighties in Tyumen, the first and only cosmetology office was mainly engaged in removing prison tattoos. The demand was huge; people signed up and waited in line for months. They came from the Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets districts. Women were especially anxious, hurrying to remove the prison serial numbers indicating their history of camp life. And some went straight to her right after release. Rozaliya Iosifovna quickly learned to distinguish between political prisoners and criminals among former prisoners. The latter always boasted of their “exploits.”

She prepared thoroughly for the sacrament of Baptism—she read a mountain of literature, wrote down important thoughts in a notebook, cleaned the apartment, set the table, and appeared before us in festive clothes with the words: “This is what I've been moving toward all my life.” The conversation with Father Maxim started right away, from the first minute, as soon as he saw her photograph in a white coat.

“Oh, and you know, we could have been colleagues. I studied medicine at first, but quickly realized it was not for me. But I do have such a cap...”

Then they went into the room, and the most sincere confession I have ever seen began (but did not hear; I had tightly closed the doors the day before), but even through them came sobs in which there was so much pain and regret that my heart literally contracted. And then, during the sacrament of Baptism, when Father Maxim asked what Orthodox name she would like to take, an awkward pause arose. The day before we had talked about anything but this. To imagine that Rozaliya Iosifovna–for family and friends, Aunt Rosa—could be called by another name seemed impossible. Father Maxim, seeing our confusion, began to name names aloud: Raisa, Nadezhda, Vera...

“Oh, let it be Nadezhda!” decided my goddaughter. And so she accepted Orthodoxy with that name. A new feeling arose, the presence of something joyful entered life. The grace of the Lord touched our hearts, and we no longer wanted to talk about anything—just sit and observe our new state.

“I Would Like to Get Even a Little Bit into That Russia”

Father Maxim's public activity deserves a separate discussion. He spoke out against so-called “civil marriages,” or simply put, cohabitation. His sermons made parishioners cry, and therefore change. It was not uncommon to see him marrying couples who had spent twenty or thirty years together, explaining to them simple truths about Christian love, and he did everything with an unfailing smile, in which one could read: “I love you.” In essence, his whole life was a sermon.

He did everything with an unfailing smile, in which one could read: “I love you”

He could easily call and say: “Today we have a holiday; we will be putting cupolas on the church, come.” And we rushed across the whole city to share this joy with him. And once I happened to see how Father Maxim talked with his mother-in-law. Before me stood a happy woman whose son-in-law was infinitely grateful to her for her daughter. She saw it, felt it, and literally glowed. As in any strong marriage, they and Matushka had children one after another, four in all.

And then in that period when it seemed life was settling into a steady course, trouble came to the house, which had long been belied by the pallor of the face and some sluggishness in movements. The beginning of the post on social networks from August 4 looked like this:

“Dear brothers and sisters! I have been undergoing treatment for one year and eight months. Diagnosis—blood cancer...”

He had a month left to live. I remembered how he taught to us repent, to humble ourselves, and said that without this there is no spiritual growth. What did he feel when he learned the diagnosis?...

Once Batiushka introduced me to Prokudin-Gorsky. It was a long time ago. Father Maxim, then still young and just appointed as a priest, said:

“I would like even a little bit, even a tiny bit, to get into that Russia which was Orthodox everywhere. To come as a pilgrim to the Leushinsky St. John the Forerunner Monastery, now flooded... To visit the church in honor of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos here in Tyumen. In 1930, when they blew it up, it rose high above the ground, and then collapsed and crumbled... To look into open village faces that did not know even a tenth of modern sins. I miss that Russia so terribly...”