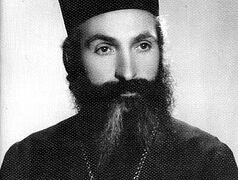

When you read or learn from the recollections of his contemporaries about the life of Serbian Patriarch Pavle (1914–2009), you come to a joyful conclusion: It is possible—and necessary—to live with Christ even in our not-so-bright times. And this “not-so-bright,” it turns out, can be overcome—by bringing the light of the Gospel into life. The very light that shone in Bethlehem, on Mount Tabor, at Golgotha, and over the Tomb of the Risen Christ. That light, it turns out, is eternal. One only needs to allow it to shine into one’s heart—and then, you see, life begins to grow clearer. Patriarch Pavle demonstrated this constantly. Here are a few memories of him that bring warmth into our winter cold.

The Cobbler Bishop

Contemporaries and friends of Patriarch Pavle recall that while he was still a teacher at the Prizren Theological Seminary—and later, when he had already become a bishop in Kosovo and Metohija—Pavle selflessly helped poor students. He gave them his own salary and the firewood allotted to him for heating, repaired their shoes, and rebound their textbooks. Later he set aside several rooms in his episcopal residence where poor students could live and eat free of charge together with the monks who also attended the theological seminary. In return, the hierarch asked for only one thing: that order and discipline be observed, writes Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavljević; 1927–2021).

Contemporaries and friends of Patriarch Pavle recall that while he was still a teacher at the Prizren Theological Seminary—and later, when he had already become a bishop in Kosovo and Metohija—Pavle selflessly helped poor students. He gave them his own salary and the firewood allotted to him for heating, repaired their shoes, and rebound their textbooks. Later he set aside several rooms in his episcopal residence where poor students could live and eat free of charge together with the monks who also attended the theological seminary. In return, the hierarch asked for only one thing: that order and discipline be observed, writes Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavljević; 1927–2021).

Two Poor Friends

There are many other testimonies to the reposed Patriarch’s mercy as well. One journalist recalls:

“People used to say about Pavle that he was very frugal, almost stingy; he always turned off the lights, saved on everything, picked up crumbs, disliked new clothes… Because of my work, I often had to be at the Patriarchate, and once I saw there, in the waiting room, a very poorly dressed old man. I needed to prepare an article about the life of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Patriarch’s meeting was long, and we had to wait in the reception area. I sat down next to the old man and casually asked, ‘And whom are you waiting for?’

“ ‘Well, the Patriarch, of course,’ he answered. ‘He’ll help me—we’ve been friends since childhood. I’m from Bosnia myself; during the war everyone fled to Germany, and I was left alone. Now I’m getting ready to go there to them, but I don’t have money for the journey.’

“I must confess with shame that my first thought was: “Ah, another beggar.” Because in those years there were many like that. ‘Good people, help however you can, I don’t have money for the trip’—a familiar story. But what struck me was the old man’s humility and his kind of bright, childlike confidence that the Patriarch would not abandon him. And that is exactly what happened.

“When, after the meeting, the Patriarch was told that someone was waiting for him in the reception area who claimed they knew each other, Pavle came out of his office, looked closely at the old man, recognized him, embraced him, and called him by name. I no longer remember the name, but I understood that the poor old man was from a Muslim family.

“The Patriarch asked how he could help. Then he almost ran to his office, brought out an envelope with money, and instructed his secretary to buy a train ticket to Germany. After that, he spent some time asking his friend about his life, his family, his children… He saw him to the door and told him to be sure to come again if he needed anything. That was how I learned a little about the life of the Serbian Orthodox Church.”

The Patriarch-“Realtor”

Patriarch Pavle’s deacon, Father Momir Lečić, recounts:

“He helped orphans very often and could not endure it when people talked about it. A simple example: The Patriarch saved up money and in the village of Mrčajevci near Čačak bought two houses with garden plots for two large families of refugees from Kosovo and Metohija, from the city of Peć. In the same village he bought another house for a large family from Kraljevo—there were nine children there. Before that, the family had been living in a metal container of fourteen square meters. I know many other similar cases. For example, a woman, a refugee from Prizren, came to the Patriarch and tearfully told him that her daughter had stopped growing—some serious illness. But, she said, she had heard that in Switzerland there was some good medicine, though the price was completely beyond their means. What did the Patriarch do? He called a Serbian priest in Zurich, described the situation of the family in need, and the very next day that priest sent with a pilot some extremely expensive medicines, which truly helped the little girl overcome the illness. Later, that same priest helped raise three and a half million for the poor in Belgrade.”

“And How Am I Supposed to Act?”

The same deacon says:

“Pavle also never took the salary that was due to him as Patriarch. He paid for his basic needs out of his meager pension. And he often paid scholarships for poor students—for example, one African student who was studying at the medical faculty in Belgrade. Or he supported one well-known academic among us. There were very many such cases in the Patriarch’s life, and I think an entire book could be compiled simply by listing them.”

Radmila Radić recounts the following episode in her biography of Patriarch Pavle:

“Once, during the war, he looked out the window and saw a group of refugees standing in the courtyard of the Patriarchate, out in the rain. Pavle went outside, opened the massive wooden gates, and invited them to come into the house to rest and dry off. When some staff members objected, saying that ill-intentioned people might enter together with the group, he replied: “And how, in your opinion, am I supposed to act? Sleep in warmth and watch children get soaked by the rain and shiver with cold?!”

Discerning Strictness

Patriarch Pavle used to say: “The Risen God is my witness: I could come and beg on behalf of our suffering brothers, sisters, and children—in churches, in hospitals, in wealthy restaurants, and in luxurious mansions. I would stand there and ask for help.”

Pavle taught the Serbian people that without mercy toward one’s neighbor there is no salvation; that all our possessions—both spiritual and material—are a talent, a loan given for a time, for which one day we will have to give an account before the Lender, the Creator and Lord. Did we use this loan wisely, according to conscience, with mercy, without vanity or self-display? Did we act according to the example of the saints, who not only gave up their possessions and “comfort,” but gave their very lives for their neighbors, following the example of Christ?

Such reasonable stewardship of this divine “loan” implies both the utmost caution and a categorical rejection of dishonesty, laziness, and drunkenness—everything the world calls “enjoying life.” Such “enjoyment” leads to vice, toward which there can be no indulgence, according to the apostolic commandment:

If any would not work, neither should he eat (2 Thess. 3:10).

This patristic caution and strictness Pavle once demonstrated in practice. A certain beggar constantly asked him for money “for bread,” but spent it on drink. When the Patriarch learned that the money was doing harm, he began buying the man bread himself—but the shameless beggar would exchange it for alcohol. Then Pavle started breaking the bread in half, so that it could not be resold. After that, the beggar never appeared before the Patriarch again.

Mercy does not mean indulging vice; Christian strictness and discernment are essential. And Patriarch Pavle was not stingy—he was discerning. Christianly discerning. That is a quality we could all use more of.