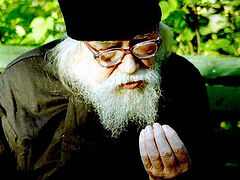

Archimandrite Melchizedek (Artiukhin), an Optina monk and head of the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul—the Optina Monastery podvorye in Moscow—talked in 2017 with the website Orthodoxy and Modern Times about the great Russian elder of recent times, Archimandrite John (Krestiankin).

Good afternoon, dear friends. In today’s talk I would like to share with you some memories of a righteous man of our own time, of the reposed all-Russian elder, of the monk who labored in the Pskov-Caves Monastery—the ever-memorable Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), who fell asleep in the Lord on February 5, 2006. He was called “the all-Russian spiritual father,” and he was known as “the Paschal priest.” The Lord granted me the blessing of knowing him personally, of visiting the Pskov-Caves Monastery, of resolving difficult spiritual questions with him in his cell, and of receiving his answers at the very beginning of my monastic path.

Good afternoon, dear friends. In today’s talk I would like to share with you some memories of a righteous man of our own time, of the reposed all-Russian elder, of the monk who labored in the Pskov-Caves Monastery—the ever-memorable Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), who fell asleep in the Lord on February 5, 2006. He was called “the all-Russian spiritual father,” and he was known as “the Paschal priest.” The Lord granted me the blessing of knowing him personally, of visiting the Pskov-Caves Monastery, of resolving difficult spiritual questions with him in his cell, and of receiving his answers at the very beginning of my monastic path.

Books about the life of Father John have now been published. One remarkable book, The Memory of the Heart, was written by a person close to him, who spent her entire life at his side—the servant of God Tatiana Smirnova. There is also another book entitled The Bright Elder: Father John (Krestiankin). And under the impression of these books and of the grateful memories of Father John shared by many people, I too would like to offer you some of my own specific recollections and episodes, for spiritual benefit and edification.

I first met Father John in 1989. I came to the Pskov-Caves Monastery and asked him specific questions about the spiritual life. One such question was this: To what extent should we combine spiritual life and obedience in our lives? Monastic life and obedience, or one’s working life—as in the case of laypeople—how are they to relate worldly life and spiritual life, and what should be the proper measure and connection between them? And he explained, figuratively, by means of a parable, what our life ought to be like.

He said: “You know, once upon a time in Russia, before the Revolution, there used to be attractions—a circus would often come to the fair, and there would be various performances. One of these attractions was called, ‘A Live Peter the Great for Twenty Kopecks.’ A tent was set up, and inside the tent there was a huge spyglass. A person would enter and begin to look through the spyglass in order to see the living Peter the Great. The attendants would say, ‘Well, adjust it.’ He would adjust it. ‘Adjust it more strongly.’ He would adjust it even more. And then, when nothing came of it, they would ask him, ‘Well, what is it? Do you see him?’ ‘No, I don’t see anything,’ he’d answer. And then they would say to him, ‘Well, really! What did you expect—to see a living Peter the Great for twenty kopecks?’ And that was the end of the attraction.”

This example may, of course, be fictitious, but then Father John went on to explain and show what it meant. He said: “So it is with us in our lives—we often want to see the living Christ for twenty rubles or twenty kopecks. No. One must labor, one must strive, one must live an intense spiritual life, because a man reaps what he sows; he who sows sparingly will reap sparingly, and he who sows generously will reap generously.”

And Father John’s answer was in harmony with an answer found in one of our Patericons. When an elder was walking with his disciples past a sown field, he saw a man reaping in that field. He approached him and said, “Give me some of your harvest.” Then the peasant said to the elder, “Abba, did you sow anything in this field that you might reap it?” “No, I sowed nothing.” “And if you sowed nothing, how do you expect to reap anything from it?” The elder withdrew, and the disciples withdrew in confusion. They returned to their monastery and asked their teacher, “Tell us, why did you ask him about the harvest?” And then he said to them, “I asked this for your sake, so that you might see that if you have sown nothing in worldly matters, you will reap nothing. It’s all the more so in the spiritual life.” If a person does not strive, does not labor, does not pray, does not love going to services, the Church, his home rule of prayer, and cell prayer, such a person will hardly reap anything in his life.

Once I asked him another question. At that time I was serving as the steward in Optina Monastery, and the monastery was only just beginning to be restored. This was a time when a thaw had only just begun; people had only just begun to speak openly about faith after the millennium of the Baptism of Rus’, and we ourselves could hardly believe that it had suddenly become possible to restore and build everything again. Would it last long? Now when we hear all this it may seem strange to us, but then… We had lived through the time of atheistic godlessness.

I asked him this question: “Father, is it worth now to devote ourselves entirely, with full effort, to the restoration of the ruined shrines and monastery? Perhaps those times will return? Perhaps we should concern ourselves only with prayer, and do whatever we can little by little to restore the monastery and its churches?” And then he said, “You know, we must restore the churches of God, because they have been entrusted to us, placed into our hands, and we will puzzle people if we do not restore them.

“And we must also reveal to the world,” he said, “the beauty of the Orthodox spirit through the churches, through frescoes, through icons, through holy relics. People who come in are often first struck by the beauty of the divine services, the beauty of the church, the beauty of its inner fullness. A person may not yet know the hymns, the Gospel, the Church Slavonic language, or the liturgical texts, but already his soul senses that this is another space, another time, another atmosphere. As they say of our churches, it is heaven on earth.”

The future Metropolitan Tryphon (Turkestanov) was once a novice in our holy Optina Monastery. And on his gravestone, which is located at the Vvedenskoye Cemetery in Moscow, there is an inscription: “Children, love the temple of God. The temple of God is heaven on earth.” When Optina Pustyn was being restored, beginning in 1988, very many people of different ranks, and social status—both political and economic—began to come there. It was often my responsibility to meet these groups and delegations of high-ranking officials, and at times I felt lost: I did not know who was who—who was a mayor, who was the chairman of a regional executive committee, what the upper chamber was, what the lower chamber was, who was a minister, and who was, so to speak, some kind of secretary. At that time it was difficult to sort this out, because before that I had been in the seminary, there had been monastic life, and suddenly it became necessary to communicate with secular people who spoke about political events and news of which I had not the slightest idea.

And I asked the elder the following question: “Father John, given my obedience and my position in the monastery, is it permissible for me to take look at the news through the media, so that I might be able to speak with such people in their own language and have some understanding of the political and economic situation in the country?”

Again he answered my question figuratively, with a story. He said: “You know, Father, in our Church there was a famous metropolitan who was engaged in public activity and represented our Orthodox Church abroad at various conferences, symposia, and other public gatherings. And once he was at a conference devoted to the struggle for justice and peace throughout the world. He represented our Russian Orthodox Church. The conference went very well, and afterward a formal banquet was given. And at this banquet—or rather, during it—twenty-seven dishes were served. Only our renowned metropolitan made it to the very last dish. Why? Because when the dishes were served—the first, the second, the third—people who weren’t aware of the order of things pounced on the first dishes that were brought out, and by the time the middle and final dishes arrived, many of them no longer had room in their stomachs. But our metropolitan tasted just a little of each dish, and thus made it all the way to the last one.”

And so Father John, figuratively, through a story, through this parable, showed that one should not, perhaps, immerse oneself in the surrounding circumstances in excessive detail. Yet both a clergyman and a person placed at the head of a parish, a monastery, or a church organization certainly must understand the situation in which we live.

Once I asked him another question: “Father, you know, many people say that these are difficult times, a hard situation, that we have some kind of tense and troubled religious climate. And that generally speaking many people live not in a Paschal spirit, but in a certain spirit of despondency and pessimism, even within religious life.” Then Father John said, “You know, I believe that our present situation in church life (this was around 1990–91) is such that seminaries and academies are opening, so much spiritual literature is being published. We now have such freedom in the Church as has never existed at any time in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church—neither before the Holy Synod, nor under the Holy Synod, nor after it. We can say that we are bathing in grace.”

I mentioned Moscow, how many people say that Moscow has become a kind of Babylon. And he said: “What sort of Babylon is this, when Moscow was called the ‘forty times forty,’ and even now—how many churches there are in it, how many open monasteries, how many shrines, relics, and wonderworking icons! Can one really call Moscow, with its shrines, a ‘second Babylon’? No. In spirit, it can be called a second Jerusalem.”

Such was his spiritual view of our religious and spiritual life. He would say: “We are now bathing in grace. For whereas formerly, in order to write a dissertation, a student had to compose a scholarly work on church life, now I think that if he were simply to list the titles of the books being published today, if only in general terms, that alone would be grounds for awarding him PhD. in Theology.” Just list the titles—all the books, which at that time already numbered several thousand.

I once asked Father John yet another question: “Father, tell me, how should one combine his obedience—constant care from morning to evening about construction, about the restoration of the monastery, the vanity of vanities throughout the whole day?” I think the same question could be asked by any person who works from morning till night, occupied with providing for his own family. In such a life, moments for prayer and spiritual life are carved out somehow—or perhaps only Saturday and Sunday.

To this Father John replied as follows: “You know, Father, our life should resemble a layer cake—pastry, cream, pastry, cream, and powdered sugar on top. If our cake consists only of pastry, it will be tasteless. If it consists only of cream, it will be too cloying. But if the pastry alternates with the cream—pastry-cream, pastry-cream, pastry-cream—and powdered sugar on top, then the cake will be sweet. The pastry is our labors, our worldly cares. If our whole life consists only of them, then such a life will not be sweet. If we have only cream—that is, only prayer from morning till night, which in practice is impossible in our life—then that too would be wrong and would not effective. Everything must be harmonious and measured—our labors should be interwoven with prayers. And not necessarily long ones—very brief ones will do: ‘Lord, bless.’ ‘Lord, help me.’ ‘Lord, I thank Thee.’ The ‘Our Father.’ The Jesus Prayer. And so our labors, alternating and interwoven with prayers will be a sweet cake for Christ.”

I asked, “And what, then, is the powdered sugar?” He replied, “The powdered sugar is humility. Because if labors and prayer have no humility, then, as the Optina elders used to say, where there is humility, there is everything; where there is no humility, there is nothing.”

And when I spoke to him about difficult relationships between people, or among the brethren, or about spiritual children who also experience problems in their families due to misunderstanding, stubbornness, or unwillingness to yield, he said: “Yes, indeed, in our time two words have become like unbearably heavy, hundred-pound weights.” I asked him, “Father, what words are those?” “They are the words ‘forgive’ and ‘bless,’” he said. “What effort, what difficulty, what labor is there in picking up the telephone and calling the abbot to ask for a blessing for this or that matter? Yet everyone acts according to self-will, and everyone acts arbitrarily.”

And Elder Ambrose of Optina used to say: “Your own will both teaches and torments: first it torments, and then it teaches something.” And Abba Dorotheos said that all the snares of the devil are undone by the words “forgive me”. And so we ought more often, in our daily life, among brothers and sisters, among relatives and loved ones in our families, to pronounce from the heart, with understanding and awareness, these words “forgive me” and “bless.” If deeds follow these words, then many problems in spiritual life can be resolved in good, the best, and holy way.

In a conversation with Father John I once asked him about the Typikon, because all the services and all the rites are laid out in full detail in the Typikon and the service books; but when they all come together… What then is the proper measure of observing the Typikon in our contemporary life and in our circumstances? And he said: “You know, when I was ordained in 1945 in the Church of the Nativity of Christ in Izmailovo, and I was a young and beginning priest, during my first week it so happened that the rector fell ill and was only able to come for Sunday Vigil. On Saturday I served the Divine Liturgy, then a moleben, then a pannikhida, then a baptism, then Unction—and so I performed everything according to the full program, letter for letter, as it was written in the service book and prescribed by the Typikon. And when I went into the altar to rest a little and sit down, I suddenly saw that the rector had come into the altar. He was surprised, looked at me and said, ‘Father John, are you already here?’ ‘Yes, I’m already here. I haven’t even left.’ When we looked at the clock, it was a quarter to five in the evening—that is, time to begin the All-Night Vigil. And so, from morning till evening, I had served everything according to the full program; but by the time of Vigil my legs were practically giving way. “And so,” he said, “everything must be observed in relation to the Typikon with discernment and according to circumstances. When there is an opportunity, we perform individual services in full accordance with the Typikon and in full measure. But when everything comes one after another, and there is only one priest, of course all this must be done according to one’s strength, and in proportion also to the strength of the parishioners and the spiritual situation that has taken shape in the parish—because, as the holy fathers told us, measure adorns all things.”

From the history of the Pskov-Caves Monastery, we know that in 2003 President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin came to the monastery and spoke one-on-one with Father John in his cell for forty minutes. And when I was at Father John’s funeral, in a corridor of the monastery I saw a photograph of the President with Father John. Those monks who witnessed that meeting recount that afterwards Father John was uplifted, in a very joyful state of spirit. That is, the meeting undoubtedly had an effect on the President, because Father John, with his love, his forbearance, and his profound wisdom, could not but influence him, could not but impress him with his spiritual depth. And we know—and I was a witness—that on the day of Father John’s repose, or rather on the day of his funeral service, a message of condolence from the President was read aloud, because he personally knew this man, this renowned elder, this, one might say, all-Russian spiritual father.

And when, after the funeral, which took place on March 7, 2006, we were returning to Moscow, I was traveling with a priest. I asked him, “Father, do you have any personal memories of Father John?” He said, “Yes. It was rarely possible to visit Father John—approximately once a year during my vacation. And I once asked him: ‘Father, it is not always possible to ask you directly for a blessing in one difficult situation or another. When there is no opportunity to speak with you and ask your counsel—whom would you bless me to consult in difficult spiritual circumstances of life?’ And he said to me: ‘You know, Father, counsel with three: with your mind, with your soul, and with your conscience. And when all three are in agreement, then act as they prompt you—of course, having first sought a blessing from the Lord.’”

And so we too, dear brothers and sisters, should find if possible a spiritual father—a priest with whom we can resolve our spiritual problems. And all the holy fathers say that whoever seeks with prayer and humility will surely find. There need only be sincere faith, trust, and obedience to one’s parish priest, who in time may become a spiritual father, a spiritual guide for life. Just as a local physician helps a person recover from bodily illness, so also, the role of a spiritual father in life is to help a person find Christ, to help a person live according to the Gospel commandments.

And therefore, dear brothers and sisters, I wholeheartedly advise you to certainly, and perhaps in the near future if there is such an opportunity—to acquire books about Father John, especially his letters and his biography.

And I think that through his holy prayers, the radiant image of Father John, his counsel and instruction, will undoubtedly help us to make sense of difficult moments in our spiritual life, to find answers to the many questions that arise along our spiritual path. For his life, his spiritual experience, was tested by much labor, by many holy fathers, by a life of arduous monastic and priestly prayer. And through the prayers of Father John, thanks to his blessed memory and his spiritual experience, we hope that we too will find the right and true path toward the fulfillment of the holy commandments of Christ.

Amen.