The

Mount of Olives is one of the holiest places on the

earth. It is first mentioned in the Bible over a

thousand years before the birth of Christ, in the

Second Book of Kings, where one finds described the

expulsion of King David from Jerusalem and his

withdrawal to the Mount of Olives for prayer (II

Kings 15:23, 30-32). It was here also that the

Prophet Ezekiel beheld a vision of the cherubim and

the glory of the Lord (Ezek. 11:22-23). All four

evangelists likewise recount for us the principal

events in the Savior's earthly life, all of which are

connected with the Mount of Olives. The summit of the

Mount, for example, witnessed the prophecy of the

final days of Jerusalem (Luke 19), of the Dread

Judgment (Matt. 24), the Lord's parting instructions

to His disciples, and the foretelling of Peter's

denial. The Savior loved the Mount of Olives and

spent nights there in prayer. On Holy Thursday,

following the Mystical Supper on Mount Sion, the

Master and His apostles, "having sung a hymn,

went out into the Mount of Olives" (Matt.

26:30). There He promised to meet His disciples in

Galilee after His Resurrection (Matt. 26:32; Mark;

14:28). And this, of course, is where He ascended

into heaven, as is recounted in the Acts of the Holy

Apostles (Acts 1:12). Olivet was also the place where

the palace of Herod stood, and where Joanna, the wife

of Chuza, buried the precious head of St. John the

Baptist after his execution, where it was discovered

by the ascetic Innocent in the 4th century, as we

read in the Menologion under the date February

24th.

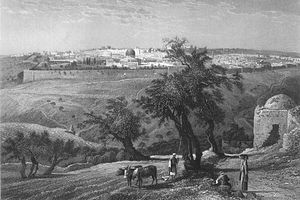

View of the Mount of Olives from Mount Zion. From vol. 1 of Picturesque Palestine

It is natural that the Mount of Olives became a place reverently venerated from the very beginnings of Christianity. Under the patronage of the holy Empresses Helena and Eudocia, and of the Emperor Justinian, many magnificent churches were erected on the Mount. Among them was the Church of the Ascension, built by the Empress Helena on the site of the Savior's Ascension. On the feast of the Ascension, many processions would pass from the Holy Sepulcher to this church. Eyewitnesses relate that, on this day, so many lamps were lit on Olivet that the whole mountain appeared to be on fire. It is interesting to note the custom of the time to build churches on Olivet in such a way that the congregation could look above themselves into the very heavens into which the Savior ascended. In all, there were twenty-four churches on the Mount.

The Mount of Olives also became one of the first centers of monasticism in Palestine. The multitude of caves on the Mount were thickly populated with ascetics, a fact eloquently attested in the Lausaic History of Palladius. Here, also, the venerable Melania the Roman founded two convents.

All of these monuments of ecclesiastical history were destroyed and rebuilt several times. But after the siege of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187, the Mount of Olives was given over to sheikhs, who demolished the monasteries and other buildings. Those churches that remained fell into utter desuetude. The area was totally devoid of human habitation until the 1860s, when Christians began to settle on Olivet again.

Here

it would be appropriate to recount in brief the story

of the Russian pilgrims' attraction to the Holy Land,

and the founding of the Russian Ecclesiastical

Mission in Jerusalem.

View of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olive. From vol 1, Picturesque Palestine.

"The Holy City of Jerusalem and the Holy Land have attracted the attention of the Russian Orthodox people from the earliest times. The holy Prince Vladimir sent an embassy to the Near East in the year 1001. In 1062, the monk Barlaam of the Monastery of the Caves in Kiev went to the Holy Land on a pilgrimage, and by the 12th century pilgrimages had already reached massive proportions," writes Archpriest Alexander Trubnikov. "From the Russian literature of the period, we know of the 'Travels of Abbot Daniel', who, in the company of a group of pilgrims from various regions of Russia, toured the Holy Land, visiting all the holy sites. Abbot Daniel conversed with monks and princes. As a 'representative of the Russian land,' he was met with respect and attention everywhere he went. From the second half of the 14th century, the record of the monk Stephen of Novgorod has been preserved; from the beginning of the 15th century, the description of Hierodeacon Zosimas of Kiev; and from the 17th century, that of 'poor Basil, surnamed Gogora.' The records of the merchants Tryphon Korobeinikov and Yuri Grekov, who were sent by Tsar Ivan the Terrible to Constantinople, Jerusalem, and Antioch to pray for the Tsarevich Ivan, have been also preserved.

"The lure of the Holy Land," Archpriest Trubnikov continues, "did not diminish with the passing of the centuries. We have seen that the state policy of the Russian Empire, as soon as it became involved with world affairs, was constantly and persistently concerned with the Christians of the Near East. The activities of imperial policy were an expression of the national concerns of the entire populace of Russia. The Orthodox patriarchs of the East were frequently invited to Russia where they were met with honor and were invited to take part in the activities of the Church of Russia. Thus, Patriarch Macarius of Antioch participated in the councils of 1656 and 1666, cooperated in strengthening the reforms of Patriarch Nikon and reassured the clergy who were troubled over the rise of the Schism. A particularly close bond was established in 1847, when the Most Holy Synod of the Church of Russia sent its Ecclesiastical Mission to the Holy Land, the objectives of which included: representing the Church of Russia before their Holinesses, the patriarchs of the East; championing Orthodoxy; and rendering assistance to pilgrims.

|

|

"Archimandrite Porphyrius (Uspensky) was appointed chief of the Mission. Other members were Hieromonk Theophan (Govorov),[i] a graduate of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy, who subsequently became Bishop of Vladimir, (later he withdrew to become a recluse in Vysha and is renowned as a religious writer). There were also two clerks. Despite the small size of the Mission's staff and its chronic under-funding (7,000 rubles a year), in five years, up until the outbreak of the Crimean War, it managed to set up an Arabic printing press at the Patriarchate in Jerusalem, which began to issue liturgical books in Arabic. Four pastoral schools were also founded for Arab clergymen—in Jerusalem, Lydda, Ramalla and Jaffa. Finally, the Mission organized the reception of pilgrims. The war terminated the activity of the Mission, but in 1858 a new mission of eleven members, headed by Bishop Cyril (Naumov), arrived to take its place. The budget assigned it was twice that of the previous Mission (14,650 rubles). Bishop Cyril, like his predecessors, was active in a great many fields. Having won the respect of the Turkish administration, the local populace and the Orthodox clergy, he was able to improve significantly the situation and conditions of Russian pilgrims sojourning in the Holy Land. The Mission accomplished much in encouraging many Arab uniates to return to the bosom of the Orthodox Church.

"This period saw the birth of an organization later known as 'The Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society'. The society took up donations for the Holy Land throughout Russia. As a result of the Society's activity, more than a million rubles were collected between 1858 and 1864. As it received these funds, the Mission proceeded to purchase plots of land sanctified by one or another event in sacred history, and to build on these parcels hospices for pilgrims, almshouses, hospitals, and other such establishments. In 1864, Bishop Cyril was recalled to Russia. About a year later, he was replaced by Hieromonk Leonid (Kavelin). He was followed in office by Archimandrite Antonin (Kaspustin), previously rector of the embassy church in Constantinople, whose role in the history of the Mission is paramount."

In

1870, Father Antonin acquired a parcel of land to the

southeast of the site of the Ascension of the Savior,

on the very summit of the Mount of Olives, which, as

Archimandrite Cyprian writes, "was the cause of

no little indignation and hostility on the part of

the Latin counterparts of our Mission."

Archimandrite Antonin (Kapustin)

During the period in question, there appeared in Palestine, under the protection of Emperor Napoleon III of France, an ardent champion of Catholicism, the Comtesse de la Tours d'Auvergne, who selected the Mount of Olives as the center of her activity; there she built a Carmelite convent, in the hope that, with time, she would be able to take over the entire mountain. But thanks to the energy and activity of Fr. Antonin, the remaining parcels of land were, one by one, bought up by him from their owners. And now the site is adorned with a spacious Russian convent.

During the excavations conducted for the laying of this convent's foundations, the following discoveries were made:

1.

Beneath the present chapel on the site of the

discovery of the precious head of St. John the

Baptist, floors were uncovered, replete with mosaics

depicting fish, birds, and ornamental designs,

similar to the mosaics at Jerusalem's Monastery

of the Cross, and ascribed to the 5th-7th centuries.

There was also an inscription mentioning a certain

"Jacob, Armenian Bishop of Metspin."

The place where according to tradition the precious head of St. John the Baptist was found (the rounded indentation), and ancient mosaics.

2. In the so-called "residence of the archimandrites," floors decorated with Byzantine-style mosaics, possibly antedating the 6th century, were uncovered.

3. In the residence of the abbots, they found a 5th century mosaic with an inscription mentioning "Theodosius, the most glorious chamberlain."

4. Many burial caves were also discovered, some with mosaic decorations.

All of this bore witness to the fact that, in antiquity, the Russian property on the Mount of Olives had been the site of a vast and rich necropolis and a number of churches, Greek and Armenian.

Not

far from the site of the discovery of the precious

head of St. John the Baptist on the Mount of Olives,

there is a stone on which, according to tradition,

the Mother of God stood during the Ascension of our

Lord Jesus Christ into the heavens. During the

excavations conducted by Fr. Antonin near this stone,

there was discovered, as he reports, "a fragment

of a golden mosaic tessarae and a multitude of small

cubes of white marble," as well as the bases of

two columns, all dating to the 6th century of the

Christian era. Also uncovered was the tomb of a 6th

century archdeacon. "Beyond doubt, a church

existed here," writes Fr. Antonin, "one of

the most ancient churches of Jerusalem. May it

someday exist again, with the blessing of Him Who

lifted up His hands here and has blessed every good

undertaking." Around this ancient church there

once existed a Greek convent (possibly one of those

founded by St. Melania). During the invasion of the

Persian King Chosroes in 614, the city of Jerusalem

was destroyed, and we know from history that 1,207

bodies of the slain were found on the Mount of

Olives. The convents were also destroyed, and the

nuns suffered martyrdom. Traces of their blood are

visible to this day as indelible stains on the marble

flagstones of the present church. So says

tradition.

The chapel of St. John the Baptist, built over the site of the finding of his precious head.

In the same place, on the remains of an ancient Byzantine church, Fr. Antonin decided to construct a temple in honor of the Ascension of the Lord, just as in 1860, fifteen years previously, he had erected a church in Athens on the ruins of the ancient Lykodemus church.

See Part 2: Fr. Antonin, Fr. Parthenius, and the Founding of the Community

From Святой Елеонъ, The Mount of Olives Convent 1886–1986, (Jerusalem: Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, 1986), 129–138. Posted on OrthoChristian.com with permission.

Nun Taisia (Ostrikova), Nun Marina (Chertkova), Vladimir Dauvaldier

I enjoyed the article very much.