The Orthodox Church in West Bengal, India

EDITORS’ PREFACE

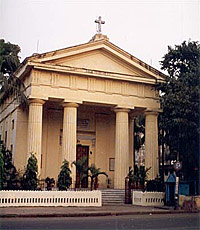

Holy Transfiguration church in Calcutta Holy Transfiguration church in Calcutta |

| Holy Transfiguration church in Calcutta |

In the middle of the first century, the Apostle Thomas arrived in India, bearing the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ. Laboring in southern India, he performed numerous miracles and was eventually martyred for the Faith in Moulapore, an ancient city near Madras. Despite being geographically separated from the rest of the Orthodox world by Muslim empires for many centuries, Christianity survived in small pockets into modern times. Although many of these groups trace their lineage back to the Apostle Thomas, none of these churches remained in communion with the Orthodox Patriarchates.

In modern times the Orthodox Church returned to India. Greek merchants built a grand and richly endowed church dedicated to the Holy Transfiguration in Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1924, but it was not until the 1980s that an Orthodox mission to the Indians was established. This occurred with the arrival of Fr. Athanasios (Antheles), a Greek hieromonk from Egypt. Basing his mission in the village of Arambah, West Bengal (about ninety miles from Calcutta), Fr. Athanasios built there a church dedicated to the Apostle Thomas. For the next ten years he traveled on foot to the surrounding villages, preaching the Gospel. By the time of his repose in 1990 he had formed twenty-four clusters of believers and translated the Divine Liturgy, a Service Book, and an Orthodox Catechism into the local Bengali dialect.

In 1991 Fr. Ignatios (Sennis), a hieromonk from Mount Athos, arrived in West Bengal to continue Fr. Athanasios’ work. Soon after his arrival Fr. Ignatios established the Philanthropic Society of the Orthodox Church. The society was formed for two reasons: first, to provide basic health care and food for the destitute and starving in a state that has practically no social services; and second, to protect the Orthodox mission from the West Bengal Communist regime, which prohibits any kind of missionary activity. While ministering to the physical needs of the Indian people, the missionaries are also able to spread the Orthodox Faith.

In 2004 Fr. Ignatios was consecrated Bishop of Madagascar under the Patriarchate of Alexandria. By the time of his departure from India, the Orthodox Church had grown to include sixteen parishes, five thousand faithful, ten priests and two deacons — all under the jurisdiction of Metropolitan Nikitas of Hong Kong and South East Asia (Ecumenical Patriarchate).

Since 1995 the Orthodox Christian Mission Center (OCMC) has been sending teams to Calcutta annually. Working with the local clergy, team-members offer catechism and seminars, and assist with the ongoing mission outreach. In 2006, an American priest, Fr. Paul Martin, traveled to India as part of an OCMC team, in order to spiritually and physically feed the hungry of Calcutta.

Our mission team leader, Fr. Stephen Callos, warned us that Calcutta would be an assault to all of the senses, and he was right. The eyes, the ears and the nostrils — but especially the nostrils — find ample reason to take offense. To say that the city is overpopulated would be an understatement. The eye is glutted, busy with impressions, and most of these are unpleasant: people squeezed together in cardboard sheds; shops all a jumble, tightly pressed within congested

stalls, bringing to mind the bas-relief on a Hindu temple — or a closed accordion; noise unremitting, the cries of peddlers and beggars, automobile horns by day and night, packs of stray dogs howling at the moon. And then there is the chaos of traffic, no emission control, few stop lights, signs or speed limits; a multitude of cars, rickshaws, and buses racing about every which way, riders like rag dolls sitting precariously atop or clinging for dear life to bumpers — all madness to an occidental. In Calcutta entire families squat near trash heaps in the streets, with plastic tarps their only protection from the elements.

But what is most offensive about this place, and most distinctive, is the smell — the scent of decay in the hot, wet air — urine, dung, and disease. An essay on Calcutta, "The City of Dreadful Night," speaks of "The Great Calcutta Stink": "It is faint, it is sickly, and it is indescribable. It resembles the essence of corruption that has rotted for the second time — the clammy odor of blue slime. And there is no escape from it."

Rudyard Kipling wrote this around the year 1890, but it is as true today as ever. Some things never change. I still have the dreadful smell of the City in my nostrils, and there I expect it will stay for some time. Fr. Stephen, who has represented OCMC in Calcutta four times, says the smell remains with him long after returning home. As far as I’m concerned, it may never go away.

While serving the OCMC mission in India I kept recalling the 17th chapter of the Acts of the Holy Apostles. There St. Paul addresses the Athenians. He sees the shrines to the gods and acknowledges the Greeks to be in all things very religious (Acts 17:22). It is telling to see Paul choosing a Greek word that can mean both "religious" and "superstitious" — and here, I think, is the key to understanding the people of India, the vast majority of whom are Hindu. These people are very religious, but also very superstitious. They worship many strange gods, and one finds little shrines to the gods on every street — shrines to Kali, Krishna, Shiva, Durga, and others. But towering above them all is Kali Temple, one of the largest temples in the world dedicated to any Hindu deity. In a section of town called Kalighat it stands, an assault to all reason and civility, decayed and primeval, just next door to Mother Theresa’s Home for the Dying and only blocks away from Holy Transfiguration Greek Orthodox Church, our home in Calcutta. Gangs of Kali priests gather in front, hawking, gesticulating. Take note: daily animal sacrifices are offered here, and the sanctum sanctorum is open to all for a price! I am accosted when passing in civilian clothes, but when in cassock I am left alone. See the viscera of goats, thrown in the streets where they decay in the dust and slime! The stink is intensified, as if the essence of Calcutta is located here, so near the ancient river Hughli.

I do not understand this dark Kali and her appeal. I do not understand her heart of darkness. Yet in Bengal Kali is most popular of all, the goddess of destruction, black, depicted with bloody tongue, a necklace of skulls and a skirt of severed arms. Cherubim Ghosh, a young convert to Orthodox Christianity and our guide in West Bengal, tells me that he had once been devoted to Kali and at first had difficulty resisting the almost incessant nagging of his mother and companions to return to the goddess. Knowing something about British India, I ask him about the Thaggies or "Thugs," a sect of Kali worshippers whose practice of ritual murder had been outlawed in the nineteenth century. He says that ritual murder is still practiced, though not openly, and that the Thugs have long been underground. Is this possible? It has the ring of a ghost story. Nevertheless, I get chills just thinking of it.

I have said that the Indians of West Bengal are superstitious. They appeal to their gods for favors and relief from suffering, which is perfectly understandable, given their deplorable living conditions. But they seem to do this with superstitious dread. The Hindus include in their pantheon Christ, the Theotokos, and even Mother Theresa. Some of them come to our Matins and Vespers services, venerating our icons and praying with us. Tim Arestou, administrator of the Orthodox orphanage near Calcutta, tells me that thousands come every year to worship Christ at His Nativity. I have the sense that they are covering all the bases, so they see nothing contradictory about turning to Christ and the Mother of God and then returning to Krishna and Kali, the mother of destruction.

But clearly these people are also very religious, and parts of what they have can be baptized, brought into Christianity. They are a pious and gracious people. When Hindus come to our services, they have an unusual way of venerating icons that is very beautiful, waving their hands over the lighted candle next to the icon and then patting their heads and faces before pressing their cheeks on the icon surface. Then they kiss and make prostrations. In our distribution of food to the poor — and we ministered to thousands in one morning — some made prostrations before us, touching our feet with both hands.

The Hindus have three major gods — Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu — and in theory, at least, they believe in a single deity. This one God or single Reality they call Brahman. Although this belief is fundamentally different from Christian belief in the Holy Trinity, it may help prepare Hindus to accept Trinitarian doctrine when they come to the true revelation of God in Orthodox Christianity.

Many know that the Hindus greet one another with joined hands, palms touching, and a bow. This form of greeting is actually widespread throughout Asia, and is interpreted in different ways by various traditions.[1] In the context of Orthodox Christianity, it may be accepted as a gesture of love, respect, and the recognition of the image of God within each person. I love this gesture and am pleased to say that it is has been assimilated into the indigenous Orthodox Christian culture.

India is such a strange world. It seemed to me another planet, or at least centuries removed from our modern existence — though in many ways I had the sense that this world is more "real" than ours. The people in Calcutta are in touch with the realities of existence, suffering and death, while we often live artificial lives, plugged into our computers and seeking escape in our pleasures and our work.

I am still overwhelmed, just beginning to make sense of my stay of nearly one month in West Bengal. Fr. Stephen Callos of the Greek Archdiocese, Fr. Nathan Kroll of the Orthodox Church in America, and I spent most of our time at St. Nektarios Greek Orthodox Church and Compound near the village of Akina about sixty miles from Calcutta. Our mission was to teach the native clergy, catechists, and the newly baptized, some of whom came long distances to participate in our seminars. This was far and away the most satisfying of all my experiences in India. Our brothers and sisters in India are hungry for the truth, and they respond with great love and gratitude. But communication is not always easy. My translator, Fr. Andrew Mondale, was excellent, though even with his help there were obstacles to overcome. Several instances come to mind. During a class on the Eucharist some were having difficulty with the Christian concept of sacrifice, until I alluded to an offering made to the god Shiva at a shrine just outside the compound gates — a potato set before a clay idol. I asked whether we should bring our potatoes, goats, fruits, and vegetables to church and place them on the altar. They replied with a resounding, "No!" "What then does God want?" Their response, almost in unison, delighted me beyond words — "He wants our hearts!" After this I was able to speak of the "sacrifice of praise" and the lifting up of our hearts as essential elements of Eucharistic worship.

During a class on creation I used the analogy of the sun’s heat when speaking of God’s creative love, His energies, and there was a misunderstanding. One man asked, "Is God the sun?" The people can be very simple and literal, but they have no difficulty understanding that God is Love.

I have said that the situation in India recalls St. Paul among the pagans. At no time was this clearer than when a question was raised concerning eating foods offered to the gods. This is a pressing matter among the Christians in India, since all of them have Hindu relatives and friends, and often they are expected to eat of these foods.-Of course, the problem is addressed in I Corinthians, chapter 8, but before India I had never expected to find this passage of any practical value, at least not in this quite literal sense.

After morning classes Fr. Nathan and I took walks in the village. The natives live in mud huts with grass roofs. I am convinced that we were some of the first whites ever encountered there. The people gaped at us — we might as well have been alien life forms — but all were excited to see our cameras. Often they would draw near and hint for us to take their pictures, as if they would thereby attain a kind of immortality. Rice paddies are all around, of course, as are shrines to the gods. And palms trees. Cobras are common. Gregory, a fifteen-year-old Christian boy, told me that a cobra had taken his father’s life two years before. He lives in a two-room mud hut with his mother, but she is the sole supporter and rarely home. He has to fend for himself, yet he is full of joy and still innocent.

In the countryside around Akina we saw a cremation site or ghat, with earthen jars, sticks, and charred human bones. After a recent burning ceremony those paying homage had placed sticks topped with rags onto the ghat. These are like little flags, and their purpose is to indicate a favor owed the deceased, so as to avoid the reprisals of an angry spirit. The pots contain body parts that didn’t burn — mostly belly buttons, I am told. But the Hindus do not always practice cremation. Cherubim explained to me that the bodies of little children and wandering ascetics (called sannyasis) are sometimes buried, since it is believed that the fire of God burns clean the souls of such as these.

Tim asked me to come to the orphanage on a Sunday after Liturgy to see the children and comfort those who had no visiting relatives. I did, and the orphans showered me with affection. In the evening, after I told them some stories, they even put on a show for me, with traditional dancing and singing. One fragile wisp of a blind child got up to sing "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star" in English, and little Despeta — who is five or six and has a fatal brain tumor — spent the whole time clinging to me. This little girl had been abandoned at the orphanage gates. She is certainly well loved here, both by the teachers and the other orphans. She is not expected to live beyond the age of eight, but in her little, special way she has brought such joy to this place, and I am sure her spirit will continue to give blessings even after she is gone. Many, both here and in America, pray for her. The orphanage is a place where God’s light shines distinctly, in the faces of children and in the work of the teachers.

On a tour of the orphanage grounds, I was shown a large shop area where children are instructed in various practical skills, such as sewing. There is a house for the blind, and at present five blind children are in residence. The blind children sit together at mealtime with their teacher, a Christian woman of sixty-two years whose face fairly beams with the love of God.

It is important to see that the ministry at the orphanage is one of great, divine love — a love distributed to all, regardless of creed. Many of the orphans are not Christian. I met Rupa, a Hindu girl of about fifteen, who is very good and has a big heart. She worries about her friends and her little sister and wants them to do well in school. I spoke with her privately, praised her and offered some encouragement. She responded warmly, happily, and I noticed that she danced for me with a special joy.

But there are many Rupas. The point I want to make is that the area where children are instructed in various practical skills, such as sewing. There is a house for the blind, and at present five blind children are in residence. The blind children sit together at mealtime with their teacher, a Christian woman of sixty-two years whose face fairly beams with the love of God.

It is important to see that the ministry at the orphanage is one of great, divine love — a love distributed to all, regardless of creed. Many of the orphans are not Christian. I met Rupa, a Hindu girl of about fifteen, who is very good and has a big heart. She worries about her friends and her little sister and wants them to do well in school. I spoke with her privately, praised her and offered some encouragement. She responded warmly, happily, and I noticed that she danced for me with a special joy.

But there are many Rupas. The point I want to make is that the good people oflndia are ripe for Christ. As I have tried to say, they are religious by nature. They hunger and thirst for Christ, and some pray with us without understanding Who He is. It is our mission as Orthodox Christians to reveal Christ in our actions, to show these dear people the meaning of God’s love. And I can assure you that this is exactly what is being done in Calcutta, in Akina, and at the orphanage.

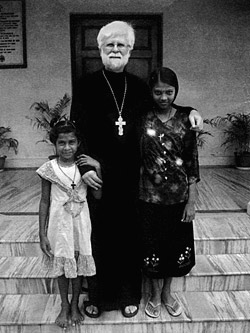

Иерей Пол Мартин с детьми из приюта Иерей Пол Мартин с детьми из приюта |

| Father Paul Martin and children of the Orthodox orphanage in India |

Every Monday at the church in Calcutta rice, beans, salt, sugar, and soap are distributed to the poor. Fr. Stephen arranged it so that Fr. Nathan and I had a chance to participate, not together but separately, since at least two priests were needed in Akina to conduct classes. Preparing for the distribution is heavy work in the heat. Many bags need to be weighed and put into stacks. During the preparation, long lines formed around the church — armies of the poor and the maimed, numbering in the thousands. I saw an old midget in rags leading his tall, blind friend. Both were crippled. I saw several people without hands or legs. Many had large tumors and growths. All were grateful to receive from us. To see the love and gratitude on their faces as I gave them food and soap, to have them prostrate themselves before me and touch my feet, was deeply humbling. I am writing this with some trepidation. I am not worthy, but the story needs to be told.

On my last day in Akina, Sarbojit Dalle, an English-speaking boy who will be baptized soon, came to me with a group, saying that the people think we have been "very good, very clear, very good teachers." "You understand us," he says, and they ask if I am a teacher at home. When I say that I used to teach English, they give wide smiles and many nods. Sarbojit explains that they all want Fr. Stephen, Fr. Nathan and me to return. He asks that we pray for them, and we ask that they pray for us.

Then we three priests give speeches. I tell the people that they will be in my heart always, that we will be joined in Christ by our prayers and thoughts and in the Sacraments. Fr. Nathan speaks briefly and sincerely — as he says, "with words locked in my heart." And Fr. Stephen finishes with loving sentiments. As usual, Fr. Andrew Mondal translates, since few of the people speak English. Then George, one of the catechists, comes forward as a representative of the people with something to say. He thanks Fr. Stephen for being so faithful over the years to the mission, and Fr. Nathan for his dedicated service. I do not know what I said or when I said it, but he thanks me for having helped him resolve some trouble he had. Indeed, God works in strange ways.

Over the weeks we all heard many inspiring stories demonstrating the strong faith of our Orthodox brothers and sisters in India. Fr. Stephen told us about a man whose employer threatened to fire him should he be baptized. He ignored the threat, and nothing happened. Eventually, the employer began expressing an interest in Christianity and even came to one of the seminars sponsored by OCMC. It takes real courage to become a Christian in India — and it takes courage to remain Christian. Converts are often rejected by family and friends, but they know that to be rejected for love of Christ is cause for rejoicing. One man told me that, when he converted and his home became a center of Christian worship, the villagers threatened him and his family with bodily harm. He remained firm, however, and now years later many in his village are Orthodox. Unfortunately, this does not always happen. And even when it does, acceptance and peace come gradually and often with pain. One of the catechists said that his parents still will not talk to him years after his baptism. He prays for a change of heart in his parents, and he longs for it. But the point is that there is a price to pay in India for converting to Christianity, and we all should be aware of this. The witness of such people is inspiring. It demonstrates the power of our Faith, as well as God’s loving-kindness and care for His children.

So I am pleased to report that the Church in West Bengal, India is alive and well. Needless to say, I’m also pleased to have survived to tell about it. Notwithstanding the terrible jet lag and culture shock, both coming and going; in spite of the swarming gnats, mosquitoes and other pests; regardless of intestinal problems and the sweltering heat and humidity — even in consideration of that Great Calcutta Stink — it was a deeply rewarding experience, one I’ll cherish until my dying day. Now just weeks after my return I long to go back, if it is God’s will. But there remains so much to assimilate, so much more to understand and talk about before I can think of returning. I am not finished with India. My writing and thinking about it has become a daily obsession. But I offer here some of my thoughts, hoping that something will capture your interest and move you to pray for our brothers and sisters there and be generous with your time and money. Missionaries are needed, but if you cannot go, please remember these people in your prayers and in your offerings.

I am sure Frs. Stephen and Nathan join me in thanking the many good and generous people who have supported our trip to India with their prayers and offerings. And we pray that God will continue to bless His Church, and that He will open our hearts to the wonderful possibilities for Orthodox Christian missionary work in India and throughout the world. Amen!

October 2006

Fr. Paul Martin is attached to the Sts. Peter and Paul Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Palos Park, Illinois, and is serving as priest at the Annunciation-Agia Paraskevi Greek Orthodox Church in New Buffalo, Michigan.

To support the Orthodox mission in West Bengal by making a donation or by becoming a missionary to India, contact the OCMC:

Orthodox Christian Mission Center

P.O. Box 4319 St. Augustine, FL 32085-4319 USA

Phone: 1-877-GO-FORTH (1-877-463-6784)

Website: www.ocmc.org

[1] In India, the accompanying salutation, "Namaste, "literally means "Not to me, but to you [I bow]."