The Pied Piper of Hamelin

The Pied Piper of Hamelin Not long ago on Facebook an argument broke out about what is at first glance an innocent object—namely, an apple. After my operation I was unable to move around, and I decided to spend the wealth that had suddenly fallen into my lap—free time—on a Facebook discussion. This was on the eve of the feast of the Transfiguration, and I and two other priests were arguing on the theme of whether or not this fruit can be eaten before it has been blessed by the Church on the feast day poetically called by our folk, “The Savior of the Apples.” Internet battles are almost always accompanied by heated arguments. This one was no exception. The truth didn’t really come out during the discussion, but some very relevant problems of modern pastoral work were delineated, and I would like to talk about them here.

To put it briefly, the essence of the argument was that the fathers, motivated by love for their flock, allowed them to taste the fruit (early apples and grapes)[1] before the feast of the Transfiguration, while I insisted on the ban, emphasizing its meaning: the remembrance of our forefather’s sin, and especially stressing the sanctions that come from violating the commandment. As a result, one particularly “loving” father (incidentally, he is currently suspended from the priesthood) accused me of misanthropy. I will cite an especially colorful fragment of his “accusatory speech”: “My spiritual father over our twenty-five-year-long relationship never once said a single judgmental word to me, never mind ‘punishment’. He explained to me that the one who stands behind the flock with the whip is a shepherd, but the one who stands ahead of them with the pipe is a pastor. You are apparently just an ordinary shepherd who doesn’t know how to love children or your flock, and that’s why you are trying to justify your sadistic inclinations.”

That is the conversation that came out in the social network, and everyone left it without giving up their own opinions. What irked me was their obsession with “Love”. If it were possible to make the first letter, already capitalized, even larger, then this preacher’s passion would have required an at least 100 point typeface. Love without rules is, in my view, the most exact way to describe this phenomenon. We habitually, even with a kind of gratification, berate the Western values system that has been “enriched” recently with such prizes as the legalization of same-sex marriages, juvenile law, the replacement of mama and papa with parent no. 1 and no. 2, and on the horizon are most likely legalized incest and pedophilia. The army of Love is confidently marching over the taboos standing unshakably on mankind’s path, upheld by the stilts of this exalted to the heavens “L”. It is the logical apotheosis of Western European humanism. But they are understandable: the consumer society, eudaemonistic culture, epicurean, Dionysian, sybaritic, and… let those who enjoy rebuking call it what syndrome they like. But how did these same stilts grow out from under the ryassas of Orthodox priests in a supposedly conservative milieu?

With a light hand quivering from laughter, Francois Rabelais (1494-1553) outlined the humanistic ideal in his “rule” of the Abbaye de Thélème: “Do as thou wilt!” And this utopia has become a reality before our eyes not only in secular Western society but also in Western, mainly Protestant, Churches and has metastasized throughout the world. This even includes part of our Eastern Orthodox Church.

To make the picture clear I will cite a description of this most progressive abbey.

“In the Abbey of Thélème there are no walls surrounding it, no schedules, and it accepts only ‘those men and women who are distinguished by their beauty, stateliness, and courteousness.’ Women are forbidden to flee the society of males, and the abbey can be left at any time. Instead of the vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience its inhabitants ‘are obliged to proclaim that each has a right to match in lawful manner, be rich, and enjoy full freedom.’ And in general, the only rule the abbey espouses is, ‘Do as thou wilt!’ The abbey has a name that comes from the Greek word, θέλημα, which means ‘will, desire.’

“The abbey and its inhabitants represent a genuine utopic ideal. The luxurious abbey has ‘9332 living rooms, each one having its own bathroom, office, cloakroom, and prayer room…’”[2]

Curiously, Rabelais[3] was one of the favorite authors of the famous English occultist and satanist Alister Crowley (1875-1947). Crowley even called his villa in Sicily the “Telema Abbey”, where he and a few followers gave themselves over to monstrous occult and tantric practices.

Rabelais’s ideas were reflected in the main principles of Crowley’s teaching, which he summed up in a few words:

- Do what you want, and that is your law;

- Love is the law, love corresponds to Will;

- You have no law other than acting according to your will.[4]

So that shows the evolution from humanism to satanism. The two legs of this monster walking around the planet are: Love and Will. Love without rules and your own will. We pray to God: “Hallowed in Love be Thy name! Thy Kingdom of Righteousness come! Thy holy will be done!”

The example one of these fathers gave in the heat of the argument is quite telling: a shepherd walks behind with his whip while the pastor walks ahead with his pipe. The first, in the author’s mind, is hatred incarnate, while the second is the personification of love. The pastoral image of the shepherd with a pipe is a favorite scene from the Renaissance. Anyone who has even once seen how a shepherd herds his flock can confirm that he walks behind the sheep and attentively watches that nothing happens to them. If even one sheep slides off a tall mountain slope the shepherd patiently searches it out and lifts it up, binds its wounds, takes it on his shoulders and carries it. If wolves come near he calls the sheep and drives the wolves away, risking his own life. This is the example that Christ gives, painting a picture of the Good Shepherd. This is true pastoral love—not with a pipe, his back to the sheep, but caring, much laboring, without sleep or rest, outwardly unattractive, sweaty, covered with dust and dirt, but so dear and close to the immortal human soul that you can’t confuse his voice with anything else.

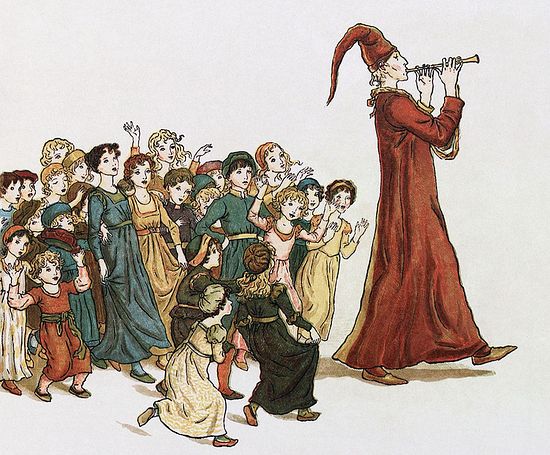

Another character comes to my mind who also likes to play the pipe and head processions—the Pied Piper, who led the children out of the Hamelin.

The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Fragment of an engraving produced from the painting by George Pinwell.

The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Fragment of an engraving produced from the painting by George Pinwell. Many Protestant Churches have played the pipe to such a point that they now marry same sex couples, allow women to become priests, and rent out their empty churches to nightclubs, bars, and health clubs. The flock is tired of listening to the pipe; they want some other form of entertainment, because they have never been taught any true spiritual work.

Humanism, which foamed up in Europe on the wave of the Renaissance, played an evil joke on it. The exchange of the theocentric consciousness of medieval man for an anthropocentric one was a true catastrophe. This anthropological revolution, which preceded everything that came after it, was made possible in Catholic society due to one mistake in the dogmatic teaching of the Roman Catholic Church, which states that with the fall, man’s nature did not change—only his relationship with God was ruined. This “not seeing” sin in human nature, which migrated from Catholicism to Protestantism, in a risky, thrilling struggle for the rights of man led finally to the legalization and defense of sin itself.

As opposed to Western European humanism the humanism of the Eastern Church is built on the principles of Orthodox teaching: from the moment of our first parents’ fall, the nature itself of the first Adam and his descendants was profoundly damaged. But we must love man, even in his fallen state, while we must hate the sin that has nested in his nature. This love through suffering is the love of the cross. It reaches its perfection by passing through the furnace of fiery temptations, becoming courageous and fearless. Though it be covered with curses, contempt, mockery, and threats, it is nevertheless unafraid of pronouncing a resolute “no” to the gendarme of liberal values. It’s honor is praised by the Apostle Paul in his hymn (cf. 1 Cor. 13), it strives toward eternity—it never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away (1 Cor. 13:8). Only it restrains the world subject to the law of entropy from total collapse. It is the salt of the earth (Mt. 5:13). And it preserves its qualities only in the light of the true faith. The moment the faith dies out, the salt loses its strength and becomes good for nothing.

Their distortion of the dogmatic teaching sank the Catholic and Protestant Churches into the darkness of carnal mindedness, from which in the final analysis will come the “man of sin”, the “son of perdition”—the antichrist. He will be the incarnation of illicit love and the deification of self-will. His forerunner and servants have put much effort into preparing mankind for accepting the “messiah”, whose proud lips, filled with lies, will pronounce blasphemy against the truth. It is he who blithely plays the pipe and leads a mankind zombified by illicit love into the abyss of eternal perdition.

And what do the holy fathers write for the edification of pastors? When you turn to our patristic inheritance you never cease to be amazed at how the instruction of our Church’s teachers to their contemporaries applies so precisely to our times also.

In his book, On the Duties of the Clergy, St. Ambrose of Milan places at the foundation of honorable priestly service the following four virtues: wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance. A servant of the Lord should not be enticed by earthly pleasures; he should manifest all the moral qualities that the Apostle Paul requires of him[5] (see 1 Tim. 3).[6]

Basing their teaching on the words of the Apostle Paul to “be all things to all men”, the holy fathers paid particular attention to the various pastoral approaches in the work of saving souls. St. John Chrysostom wrote that a pastor should be important and not proud, stern and propitious, authoritative and at the same time sociable, dispassionate and obliging, humble and not man-pleasing, strict and merciful.[7] “What testimony do we need,” says St. Gregory the Theologian, “in order to correct a manner of life and subject dust to the spirit, for there are different inclinations and understandings with men and with women, with the old and the young, those in authority and those in submission… some are taught by a word, others by example, some need a whip, while others need a bit… one must be angered without being angry; have contempt without being contemptuous; lose hope without despairing; heal some with meekness, others with humility, and yet others with rebukes, and so on.”[8]

St. Gregory the Dialogist goes into more detail about the different methods of healing infirmities in his Pastoral Rule—a special work dedicated to the problems of pastors. St. Gregory shows himself to be a subtle psychologist and experienced instructor when he teaches that a priest is allowed at times to condescend to his flock’s lesser vices in order to remove the greater ones:

“It often happens also that the soul is wounded by the infirmity of two vices, one of which acts less, the other more strongly. In such cases it is wiser to give speedier help against the vice that is more dangerous and more quickly leads to perdition. And if the soul cannot be saved from imminent death in any other way than by increasing the opposite vice, then the preacher in his teaching, acting with wise discernment, can allow the increase of one, in order to save from imminent death the one who is threatened by the other. In acting this way, he does not increase the illness but meanwhile saves the life of the sick one he is doctoring, waiting for a convenient time to effect total recovery to health. Thus, we see no few examples of the fact that many have been drawn into unrestraint in satiating themselves with various lures of food and drink, almost ready to give themselves over entirely to the enticement of the passions overcoming them; but when from fear in the struggle they make an effort to restrain themselves within the boundaries of temperance, then they are given over to the temptation of vainglory. In such people one vice can in no way be completely destroyed if we do not allow an overbalance in food for the other, so that one as if squeezes and casts out the other. What wound should be hounded more energetically if not the one that causes danger? Thus, we can allow sometimes that through the virtue of restraint arrogance might increase in a person, if only luxury might not destroy his decidedly intemperate life… allowing the lesser destroys the greater, in order that not yet having grown to that measure of perfection, in order to destroy all the evil in oneself, one might remain for the time being with the lesser fault, to at least be delivered from the greater vice (Chap. 40).[9]

The modern Christian would judge differently: “It would be better for me to eat everything and be humble but love everyone, than to fast strictly and think myself better than everyone.” However, St. Gregory sees a greater danger in love of luxury than in the vainglory that accompanies temperance.

Another holy father of the Western Church, blessed Jerome of Stridon, councils the pastor never to eat to satiety, but to the contrary, forget sometimes about lunch, or at least about dinner. And about drinking wine he says outright, “Remember, Lot was not conquered by Sodom but by wine.”[10]

And of course, at the cornerstone of priestly service the teachers of the Church place compassionate pastoral love. In a textbook on pastoral theology for candidates to the priesthood it is said that a pastor of rational sheep “must take all measures to cultivate in his heart this most exalted and eternal good—holy love for people and for the higher world. Without this quality he cannot be a pastor. A pastor without love is like the body without the soul, a flower without color, a morning without the dawn, a day without the radiant sun, or, according to the apostle, an extinguished star, wandering in the darkness of night (see Jude 1:13).

If we talk about the measure of fervency of pastoral love we briefly note that pastoral love increases with the pastor’s self-denial, the bearing of his flock’s sorrows, the continual struggle with his own self-love, with fiery prayer and unremittingly forcing himself towards works of piety.”[11]

In all of the above patristic sayings on pastoral service resounds the thought that this is the highest art there is—not playing the pipe, but many years of hard work combined with self-denial and forcing of oneself to acquire the gift of active, compassionate love, which does not smear over festering wounds with greasepaint, but patiently doctors them, pouring on them oil and wine—love and sternness.

In conclusion I would like to address our father-pastors of rational sheep: do not be afraid to be stern, first of all with yourselves. Love of neighbor can become compassionate only through suffering. Any other love is simply playing the pipe; playing without rules.