When you ascend the winding stone staircase leading to the sanctuary containing the robe of Jesus Christ in the Cathedral of St. Peter in the German city of Trier, you’ll definitely stop to catch your breath on the spacious landing half way up. Here, to the left of the little table where they sell books and Catholic souvenirs, is a door with a turnstile to the vestry (built in 1450 and rebuilt in 1900). Here they explain that one can enter for a small fee. A special key sets in motion a metal “spinner” and the pilgrims are allowed in to look at the remarkable treasures of the vestry, and venerate the relics safeguarded there.

The square shape of the room itself, like the quantity of relics contained in it, is not at all large; but here in the ancient reliquaries behind the glass you can see several great Christian shrines. One of them is the small portable altar of the Apostle Andrew, known as the precious “Trier sandal of the Apostle”.

The veneration of the Apostle Andrew in Trier goes back to the early fourth century. Then, in 320, the Roman Emperor, Equal-to-the-Apostles Constantine the Great, began the construction of a cathedral in Trier. His mother, the holy Empress Elena (she is considered the founder of this “house of God”) brought among other rare relics from the Holy Land to the “Northern Rome” the sandal of St. Andrew the First-Called and gifted it to a local Christian community.

St. Andrew was the first to follow Christ. He also brought his brother Peter to the Savior. They were both from Bethsaida, and fished the Sea of Galilee. After the descent of the Holy Spirit, the Apostle Andrew departed to preach the word of God in the eastern countries; he reached the Danube, traversed the Black Sea coast, Taurida (Crimea), and travelled to the upper Dnieper River. From there he went across the Varangian (Viking) lands to Rome and returned to Thrace, where in the small settlement of Byzantium, the future Constantinople, he founded a Christian community. Bringing the light of Christ’s truth to people, the apostle endured no little torment and suffering from the pagans. In the Greek city of Patras, where he worked many miracles of healing and converted the inhabitants to Christ, the apostle received a martyr’s death in the year 62. Before departed to the Lord, tied to the cross at his hands and feet, he taught the truth to the people for two days.

The holy Apostle Andrew was not only venerated in Trier. The traditions going around Europe about him lay at the foundation of a widespread, very ancient Life of the Apostle contained in the “Letter of the Achaean deacons and presbyters,” which dates from the sixth century. In this same century a Latin translation called “The Acts of Andrew” appears, in which a fragment of a story is included about another apostle, Matthew, whose relics are also preserved in Trier. Later this work became known under the Latin title, “The Acts of Andrew and Matthew,” and lay at the foundation of a work by Bishop Gregory of Tours, “Book on the Miracles of the Blessed Apostle Andrew” (592), in which the author testifies to the ancientness of the veneration of St. Andrew the First-Called in Gall, telling of the miracles he worked and recalling the churches dedicated to this saint. In England, “The Acts of Andrew and Matthew” were in the eighth century written in verse about the first-called apostle.

According to tradition, from 1250 in the Abbey of Saint Victor was kept the cross on which St. Andrew was crucified. In 1438 the Duke of Burgundy Phillip the Good took a piece of this cross from here to his palace chapel in Brussels. The Apostle Andrew the First-Called was considered as the protector of Burgundy, and his cross became the symbol of that state. Incidentally, on the flag of Scotland there is a St. Andrew’s cross, and the apostle is considered as the patron of that country also. His relics appeared there in the eighth century (other sources say the fourth century). St. Andrew was also particularly venerated in Austria, Spain, and Ireland.

In Rome, St. Gregory the Great the Dialogist, while he was the Roman pope, founded from 574-575 a monastery named for St. Andrew the First-Called.

The veneration of objects that once belonged to the saint especially spread in Western Europe during the rule of Pope Gregory I. He himself sent the keys to the Apostle Peter’s grave to Rome. Incidentally, in the vestry of the Trier Cathedral of St. Peter are one of these keys and two partial links from St. Peter’s chains.

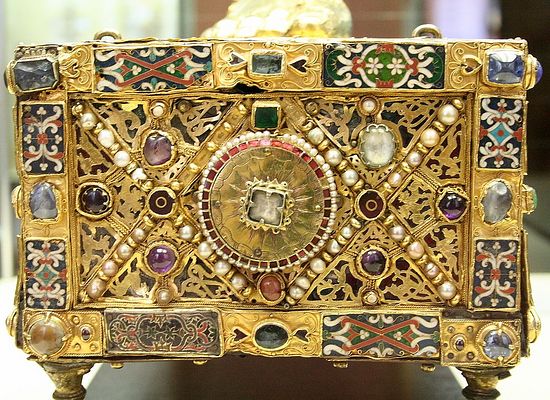

At an expedition dedicated to Emperor Constantine the Great held in Trier in 2007 it was possible to learn how Christian shrines were preserved in early medieval Europe. At first dark glass bottle were used to save relics, as well as small boxes or crosses. In the eighth century, special purses were used, and from the late ninth century on, reliquaries of various forms were used—ostrich eggs, figures, church buildings, and so on. A Russian pilgrim in the Trier vestry would undoubtedly find the original reliquary case with gold filigree in the Byzantine style (eighth century) quite interesting. The text on the sign under it says that the reliquary was made by “Byzantine or Russian masters”.

In the late ninth century reliquaries appear that speak by their form about the relics they contain: a piece of a skull would be found in a reliquary shaped like a head, and a piece of an arm would be in a case shaped like an arm. This is how relics were presented for veneration.

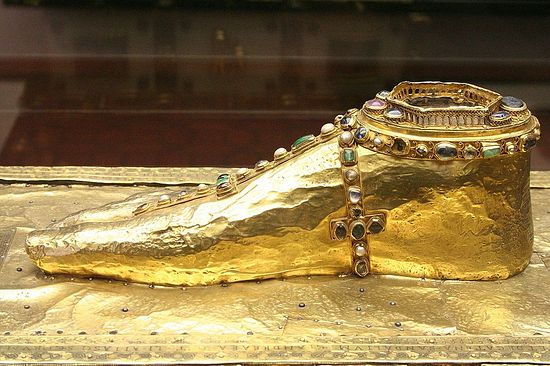

The upper portion of the portable altar of the Apostle Andrew is made in this style. It is a gold-guilt right foot, crossed in several places by thin, elegant straps, decorated with precious stones. From a distance it creates the impression of a foot wearing a sandal, but looking closer we see that only the straps are present, while the sole is not. In fact, a consultant from the the cathedral confirmed that the reliquary in the form of a gold foot on the portable altar of the Apostle Andrew, which was made by craftsmen under the direction of Archbishop Egbert between 977 and 933, does not contain the sandal itself, as some tourist brochures and websites of Western parishes say, but only a part of the strap of St. Andrew’s sandal. Furthermore, to the portable altar belongs the covering from the Apostle Peter’s staff and a nail reliquary (made in 933), where one of the nails that nailed Christ to the Cross was kept.

According to tradition, holy Empress Helen brought to Trier the sandal worn on the right foot of the Apostle Andrew the First-Called. But because it was kept (like other relics in the Trier Cathedral) for a very long time covered over in a stone wall, only a part of the strap remained.

St. Andrew’s portable altar was intended for use in the services in Trier and other cities. It was made by local masters out of fine and durable materials in accordance with traditions of the late 900s.

During services, depending upon the location of the portable altar in the church, the area around it would be adorned with candle stands. All churchly attributes taken together were supposed to combine harmoniously, so that the faithful could easily see what was happening in the altar, what was on it, and what relics were placed nearby.

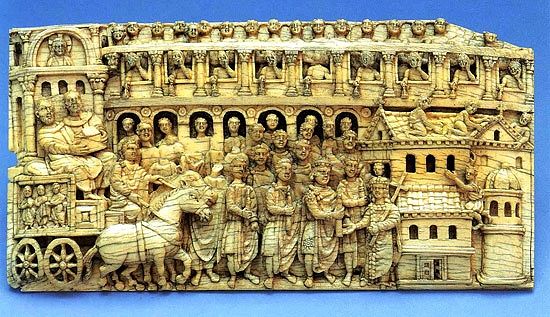

The portable altar of Apostle Andrew, like other precious reliquaries from the vestry of the Trier Cathedral, as those serving there related, were periodically taken to many different European cities for veneration. The solemn procession accompanying the translation of similar relics shown in the unique vestry exhibition, was masterfully depicted on ivory by Byzantine artists in the fifth or sixth centuries.

Depiction of a procession with a reliquary, ivory. Byzantium. 5th or 6th c.

Depiction of a procession with a reliquary, ivory. Byzantium. 5th or 6th c.

In the Trier museums can be seen several examples of shoes from the first centuries of Christianity, including sandals. Inasmuch as we were talking about the latter, it deserves recalling that sandals in apostolic times were the most popular kind of foot covering. They were of a very simple construction. A piece of thick leather was cut to the size of the sole of the foot, and fastened to the foot by straps. A long, thin leather strap was passed between the big and the second toes and tied around the ankle. Or one strap wrapped around the heel and met with the other end, was passed between the big and the second toes and tied to them. Only women had decorations on the straps. When a man sold his property, in the Eastern tradition he would take off his shoe and hand it to the buyer to show that he was giving him ownership rights, as did Boaz’s relative (cf. Ruth 4:7).

The feet were comfortable and cool in sandals, but this sort of shoe left a large part of the foot exposed, and thus the foot was usually covered with dust. Before entering the sanctuary (cf. Joshua 5:16) or someone else’s home the shoes were usually removed; in fact, the right sandal would be removed before the left. As a rule, untying the sandals, removing them, and taking them away was the duty of slaves (cf. Mt. 3:11; Jn. 1:27; Acts 13:25). From this probably comes the expression, “they sold the poor for a pair of sandals” (Amos 2:6). Because sandals were open and did not protect the feet from dust, washing the feet was the first service shown to a visitor (cf. 1 Kings 25:41). Servants were supposed to wash the feet of guests. For the first Christians, the washing of a guest’s feet was considered a Christian act of love (cf. 1 Tim. 5:10). The Lord Jesus Christ Himself gave this example by washing the feet of His disciples (cf. Jn. 13.3-16).

The portable altar of the Apostle Andrew has been kept in Trier for over a thousand years now. This reliquary is also a remarkable work of art by medieval masters. Now more and more Orthodox Christians are coming to Trier to venerate this relic and other great holy relics preserved in the Trier Cathedral, such as the robe of Jesus Christ and the honorable head of the holy Empress Helen.