The Letter to the Hebrews makes it clear. As Orthodox Christians, we are the heirs of a long tradition of witness. This tradition embraces not only the whole of Church history beginning with the New Testament but includes the Old Testament as well. We need to be careful, though. There is a tendency, a temptation really, to think of Holy Tradition, this tradition of witness, in abstract terms. The evidence of our faith is not found in the history of ideas but in the testimony of those men and women who have gone before. Tradition doesn’t exist in a chemically pure form but is embodied in the lives and deaths of those who are “well attested by their faith.”

Writing in the second century, St Justin Martyr expands this tradition of witness to include what we might call a witness of desire. Specifically, Justin saw how in their pursuit of Truth and Virtue the pagans also participated in preparing humanity to receive the Christ. Or, to say the same thing in a slightly different fashion, God uses our desires to draw us out of ourselves and to Him.

Again, in both the tradition of witness and the witness of desire, what we encounter are not abstract ideas but concrete human beings. Together with Moses, we meet in the tradition of witness not only “Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, of David and Samuel and the prophets” of the Old Testament but also the “apostles, … prophets, … evangelists, and … pastors and teachers” of the New Testament who labored “for the edifying of the body of Christ, till we all come to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to a perfect man, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ” (Ephesians 4: 12, 13, NKJV).

To the public witness of revelation, there is the secret witness of the human heart and its desires. Here we meet not only Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle but Homer, Aesop, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and the myriad philosopher, playwrights, poets and ordinary men and women who throughout the ancient world who longed to see “what was promised.”

While different in form, one public, the other hidden, both the tradition of witness and the witness of desire remained unfulfilled until the coming of Christ and His Church. The whole human family before Christ, Jews as well as pagan, finds its perfection in Him and in His Body the Church and “apart from us they should not be made perfect.”

This last statement sounds as arrogant to modern ears as it did scandalous and foolish to those who lived at the time of Christ. And if what we profess is merely a philosophy—albeit a true philosophy—we are guilty at least of arrogance if not something quite worse. Even when true, any human philosophy is necessarily limited. No matter how true or noble, merely human ideas and ideals inevitably become an ideology. Charity becomes control; virtue is replaced by mere conformity; obedience by servility; and awe in the presence of God a pervasive and deadening sense of anxiety.

But what we profess is not a philosophy, even if (in the hands of some) it has become an ideology.

What we profess instead is human thought illumined by divine grace to become the Good News.

What we profess is the grace given to ordinary men and women so that they have the courage to bear witness to the Living God no matter what the cost.

What we profess is not mere history.

What we profess is human history transformed and transfigured to become Holy Tradition, the Voice of the Holy Spirit leading the Church from generation to generation.

What we profess is the power of God to fulfill the deepest desires of the human heart,

…to heal what is broken in us,

…to reform even the most hardened sinner and

…to raise the dead to life everlasting.

And the evidence for this? The lives of those who have gone before us. The evidence is also found in the lives of those who encountered Him Who Philip see today in the Gospel. And having encountered Jesus what does Philip do? He finds Nathanael and introduces him to Jesus.

For his part, Nathanael is skeptical; “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” Interestingly, Jesus doesn’t chastise him for his hesitation but commends Nathanael for his honesty; “Behold, an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!” Philip’s acceptance as much as Nathanael’sreservation are both acceptable before God. The former because it is a word spoken from a believing heart; the latter because it is a word spoken from a heart that longs to believe. Nathanael desires the Savior Who Philip has found—or rather, Who has found both him and Philip.

The great challenge of the Gospel is not that it’s true—though it is—but that it isn’t ours. We are the stewards of the Gospel, of a way of life that has been entrusted to us and which can only be accepted in gratitude. This is why the summit of Christian worship is the Eucharist (from the Greek word εὐχαριστία (eucharistia), meaning “thanksgiving”).

It belongs to each of us to offer our heartfelt thanks and gratitude to God. Doing so, however, requires that we offer to God a sacrifice modeled after Christ’s. I must give my whole life to God the Father, in the Name of Jesus Christ, through the power of the Holy Spirit.

I must do this even if the heart I give is, like Nathanael’s, skeptical and hesitant. I must do this even if, like many among the Jews, it is a heart bound by law and custom. I must do this even if, like the pagans, it is a heart in love with its own ideas. I must offer to God my whole heart in whatever condition I find it.

It is only when we give ourselves to God that He transform us and make us His apostles. We are each us called to be witnesses like Philip even if, like Nathanael, our faith is hesitant. No matter what the condition of our hearts, God tell us today that we too will “see heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of man.”

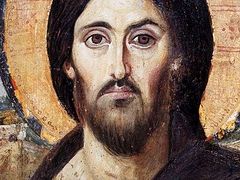

The icons that we carry today are only one of the myriad tangible reminders of the life to which we have been called. They remind us of the truth of the Gospel and the power of Jesus Christ to transform our lives today as he did the lives of the saints who have gone before us.

My brothers and sisters in Christ, to celebrate the Restoration of the Icons, to celebrate the Sunday of Orthodoxy and to profess “the faith of the Apostles; … the faith of the Fathers; … the faith of the Orthodox; … makes fast the inhabited world” (Synodikon of Orthodoxy) is to commit ourselves personally, here and now, to follow Christ and to live as His witnesses secure in His love for us and the whole human family.

In Christ,

+Fr Gregory