The woman poured precious oil of myrrh upon thine awesome and royal head, O Christ our God.

Matins of Holy Wednesday, ode eight

I have found David my servant: with my holy oil have I anointed him.

Psalm 88:20

Among the righteous of the Old Testament, few shine more brightly than King David. God chose him as “a man after his own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14), and so much that transpires in Holy Week was foreshadowed in his life. Our Lord Jesus Christ is his descendant, and in Christ’s kingship are fulfilled all the promises once made to David:

Thy seed will I establish for ever, and set up thy throne from one generation to another … He shall call me: Thou art my Father, my God, and the defender of my salvation. And I will make him my first-born, higher than the kings of the earth (Ps. 88:5, 26–27).

David died, “and his tomb is with us to this day,” but these promises were made in prophecy concerning the One who was to come (cf. Acts 2:24–35).

“The Anointed”: this is everywhere a mark of kingship; it is also the very meaning of the title Messiah or Christ. Whereas David was anointed as king by Samuel the Prophet, the Son of David was anointed not by man, but by the Holy Spirit, who descended upon Him in the form of a dove at His baptism in Jordan.

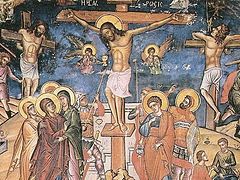

At the midpoint of Holy Week, however, we remember an occasion when Jesus was anointed, not by his “equal in Godhead,” as at Theophany, but by his creature, a woman who had “fallen into many sins” (Hymn of Kassiani).

A repentant harlot: such is the woman we encounter on Holy Wednesday, and in her we perceive a great biblical theme. How often throughout Scripture has God’s chosen but unfaithful people been likened to a harlot? For long ago you broke your yoke and burst your bonds, we read in Jeremiah, and you said, “I will not serve.” Yea, upon every high hill and under every green tree you bowed down as a harlot (Jer. 2:20). And, in Hosea: My people inquire of a thing of wood, and their staff gives them oracles. A spirit of harlotry has led them astray, and they have left their God to play the harlot (Hosea 4:12).

That Israel should have asked for an earthly king at all was an instance of her pining after the ways of the nations. Samuel tried to dissuade them, but to no avail. No! but we will have a king over us, that we also may be like all the nations, and that our king may govern us and go out before us and fight our battles. (1 Sam. 8:19–20)

And so God granted their desire—but not as a sign of favor. Samuel anointed Saul as king, but his reign was bitter, full of turmoil and envy. Where now is your king, to save you; where are all your princes, to defend you—those of whom you said, “Give me a king and princes”? I have given you kings in my anger, and I have taken them away in my wrath (Hosea 13:10–11). Indeed, so severe was Saul’s reign that, while he still lived, the Lord commanded Samuel to anoint a new king, but in secret: David, the youngest of his brothers, and all but forgotten (1 Sam. 16:11–13).

Yet after David’s anointing, Saul’s spite grew only more intense. For in David, Saul now feared the challenge of a rival, though one who had no need to impose himself or vaunt his divine election. In fact, David fled from Saul in the wilderness where, at one point, he could easily have vanquished Saul forever. Yet, Christ-like, he forbore (1 Sam. 24:3 ff).

My Kingdom, Christ said to Pilate, is not of this world (John 18:36). In the world men continue to submit themselves to the tyranny of the devil. The prince of this world, like Saul, continues to fill the land with guile and madness, furiously raging against the legitimate authority of God.

After his baptism and the descent of the Spirit, Christ was driven into the wilderness, to be challenged and mocked by the evil one. Though it was well within his power at any point to vindicate his rightful claim as Son of God, he, like David, forbore (cf. Matt. 4:1–11).

Eventually, all Israel publicly acknowledged David as their ruler, conceding that it was he who had truly been leading them even while Saul was still alive (cf. 2 Sam. 5:1–3).

Christ too was openly recognized by the people: when he entered Jerusalem. They spread their garments before him and shouted Hosanna to the Son of David! (Matt. 21:9), expecting him to lead them in throwing off the Roman yoke, thus to restore again the kingdom to Israel (Acts 1:6). But since Christ’s warfare is not against flesh and blood (Eph. 6:12), the people were disappointed of their hope, and their waning enthusiasm would soon give an opportunity for the Jewish rulers to make their move.

David, long into his reign, was betrayed by one of his closest confidants: Ahithophel, whose counsel David trusted as if he had asked at the oracle of God (2 Sam. 16:23). With David’s son Absalom, Ahithophel conspired against the king, but when his plan came to naught, he despaired and hanged himself (2 Sam. 17:23). How bitter is the Psalmist’s lament: Even my own familiar friend in whom I trusted, who ate of my bread, has lifted up his heel against me (Ps. 40:9).

These words hang heavy in the air during the last week of Christ’s earthly sojourn as Judas becomes a spy for Christ’s enemies (cf. John 13:18). Entrusted with the moneybox, the false disciple can barely disguise his greed. Feigning concern for the poor, he begrudges the woman’s extravagance as she anoints the Lord with costly oil (cf. John 12:4–6). Was Judas, even at that hour, trying to stifle a faint inner misgiving when he saw the woman’s torrent of love for the one he had resolved to sell?

The harlotry of Israel—a millennium and more of lawlessness and idolatry—all this converged as through a funnel upon Iscariot’s treacherous heart. Israel always turned aside to other gods, and Judas entrusted himself to the protection of silver. He turned his back on the true God, only to find no hope or refuge in any other. Yet his heart was already so sunk in self-deceit that repentance proved beyond him. Like Ahithophel, despairing, he hanged himself.

Yet there is more than this to tell of the fate of Israel. For, alongside Judas, holy Church also shows us the sinful woman. She too, in her harlotry, is emblematic of faithless Israel. Yet she repents. And in her compunctionate heart is gathered together all Israel’s yearning for communion with God: centuries of sacrifices, prayers, and prophetic warnings. The false disciple may betray; the leaders of the Jews may plot and interrogate; Roman soldiers may mock and jeer—but this woman, like Samuel of old, anoints in secrecy the true King of the Jews, and on behalf of her people she confesses the Messiah of Israel.

She anoints the Lord not for the sake of an earthly kingdom, which passes away, but in readiness for death and burial, to which the Lord will submit that, he might destroy him who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery. (Heb. 2:14–15).

Adam and Eve, like shame-faced slaves, hid from the footsteps of the Lord in Paradise. But freed of the guilt of sin through her repentance, this woman draws near to those same beautiful feet with myrrh and tears (cf. Hymn of Kassiani). She is redeemed through Christ and raised to the dignity of a citizen in the New Jerusalem.

As Orthodox Christians we too have been anointed with holy Chrism, that we should be raised even higher than the dignity of citizens: that we should reign with Christ for ever (cf. Rev. 22:5). Our anointing, like Christ’s, is a preparation for burial. Before we can reign with him, we must suffer with him and not deny him (1 Tim. 2:12); only through being buried with him can we be raised up to newness of life (cf. Rom. 6:4, 8). Vladimir Lossky puts it thus:

We have received the royal unction of the Holy Spirit, but we do not yet reign with Christ. Like the young David, who after his anointing by Samuel had to endure Saul’s hatred before he obtained his kingdom, we must resist the armies of Satan, who like Saul is dispossessed but still remains “the prince of this world.”1

The treacherous disciple grew faint at the sight of battle and gave himself over to evil and eternal death. But the woman, through repentance, put on the armor of salvation, fought the good fight, and took hold of eternal life (1 Tim. 6:12).

Through such warfare, a sin-loving harlot is transformed into a pure bride, adorned for her husband. Throughout the long, moonless night of this age, she keeps watch with joy for the midnight coming of the divine Bridegroom. Wise in her renewed virginity, she keeps her lamp full of oil and burning brightly. She is ready, when he comes, to be led by him into the eternal Bridal Chamber, there to partake of his delights.