In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Today we have the remarkable and blessed feast of St. Demetrios of Thessaloniki. You know about the majority of his life, you know that he was the son of the mayor of Thessaloniki, that his parents were secret Christians and didn’t even tell him about it. And only later, when he was already ten or twelve, they took him and showed him the room where they secretly went to pray to God before the icons. They told him that all the idols he heard about and the statues and temples that filled the city of Thessaloniki were demons, untruths, lies invented by the people, but the true God is the God of Sabbaoth, the Lord Jesus Christ, manifested in the flesh.

Then he came to believe and confessed God and was baptized, and when his father died, he became the mayor and received much praise and honor from the emperor. But as soon as Demetrios received authority over the city of Thessaloniki he began to close the places where people gathered to worship idols and publicly preached the true God. Having learned of this, the emperor sent him a message, that he himself was coming to hold trial over him and punish him. However, St. Demetrios did not stop, but only continued to confess Christ and strengthen the gathering places of the Christians and their abodes, hitherto secret, and helped them. He turned many to faith before the emperor arrived and threw him into prison to be tortured.

Perhaps there are three great features that distinguish St. Demetrios from other saints, as the scent of one flower differs from that of another. First, that he came from a noble family of rulers, from the mayor, and enjoyed riches and the praise and honor of the emperor. He could have counted on it in the future and cajoled himself with the hope of reaching Rome and becoming one of the emperor’s confidants, but deemed it all worthless in comparison with the confession of Christ.

This was his distinguishing feature. Other martyrs thought alike, but he especially, like those who had great wealth, left everything and turned to God and confessed Him.

The second characteristic, which I can say is peculiar, which we don’t find in the lives of other saints, is that he blessed Nestor to duel with Lyaeus who mocked Christians. It was precisely those whom he converted and helped that were taken to the arena to be killed and turned into nothing by this Lyaeus, a unique gladiator, reputed to be the strongest in the whole empire, a favorite of the emperor, mocking Christians, and, perhaps, killing them in various ways, to delight the emperor who was entertained by watching Christians in the arena.

And here some youth named Nestor, perhaps already knowing Demetrios before, came to him to ask his blessing for a contest with this Lyaeus, that he could no more mock and kill Christians. Demetrios blessed him. If we know about the Great Martyr Mina that he always stands for justice, quickly helping when you lose something, or when you are treated unfairly, when you are despised despite that you have every right to be respected—then St. Demetrios, before the face of this injustice, this malice, this flood of hatred and unrighteousness which descends upon Christians, does not behave meekly, as a lamb or dove. But his blessing possessed the wisdom of a serpent, as the Savior says,[1] and the mocking of Christians ceased.

That is, his soul burned with a desire for truth. He thirsted for it—blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness…[2] He was one of those who considered it unjust, what was happening when these people, these Christians, believers in Christ, the true God, suffered and underwent such derision. Although he knew that these Christians would not go unrewarded and that a great recompense awaited them in Heaven, still he stopped this injustice already here, on earth.

Perhaps, when a multitude of untruths, evil and adverse events one after the other bring such injustices upon us—even if we deserve them, even if we confess that they should fall upon us, that we are sent what we deserve—we can have St. Demetrios as our helper and say to him: “As then you could not bear to see the Christian race persecuted and scorned, and your blessing made the fragile Nestor stronger than the powerful Lyaeus, and he defeated him, so now do so. Pray to Christ, the Son of God, Whom you love, that He might help me.”

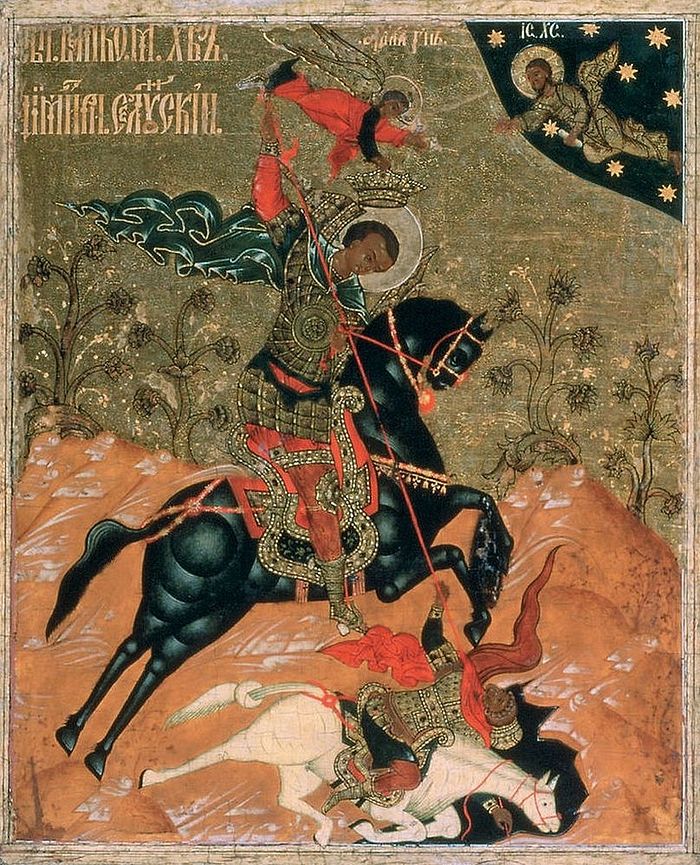

The third unique characteristic is that when they killed him, he raised his right arm—and so he is depicted in icons—when they rushed at him with spears to stab him. He raised his right arm, to be pierced in the right side, as Christ was pierced, and that by his very death he might confess Christ.

All of this we can see in several small details, and we can form an image of St. Demetrios and understand why God glorified him and vouchsafed him such esteem among people, as few saints were blessed with in this age.

Why did Nestor need his blessing? What does a blessing mean? Ultimately, it is prayer. After all, we are unable to bless by our own power, but we ask the blessings of God upon someone. Why did he need his blessing? Why does the blessing of many, or our own blessing have no power, but his had it? Beyond all doubt because he did it for God, out of love for God; he gave his life for Him.

Our prayer and our blessing have only as much power as we give to God from ourselves, and exclusively only for God, and not to please people or for the sake of glory, or the sake of honor and not that people would honor us in the future, but naturally from love for God. And undoubtedly his prayer and blessing had strength because of the many torments he was able to endure, because of the pain he was able to bear, for the sake of the cross he was able to carry on his shoulders with love for Christ, not complaining, not becoming indignant, not murmuring, but conversely, rejoicing.

You can ask yourself, why do I say “not murmuring” and how I know that he wasn’t afraid in prison when he awaited death? Perhaps, before the emperor arrived to the city, he easily performed many great acts, and then he was afraid and trembled and sat in prison in fear, thinking how stupid he was—should he stop then or do everything in secret or some other way? Maybe you think, how do we know this? We know this from that same fact that, dying, he raised his arm. And what does it mean to do this; what does it mean to die in this way?

We all know that death is terrible, that before the face of death a man becomes sincere, and therefore the ancient fathers gathered in the desert and by the manner of death of some monk, they learned what kind of life he had. Before the face of death you don’t want to pretend; it’s impossible to play with death. In your dying pains and fears, in the experience of your final moments of life, there you show who you are—you show your true colors. Thus the fathers gathered in deserts and accompanied a monk departing to that world, laboring in prayer with him, that his soul would depart more easily, that it would be sent to peace, to the palaces of the righteous. And by how he died, how he looked at death, they understood what his life was like.

So in this gesture of St. Demetrios is seen his whole life, especially his mentality, and his love for God. Before death won’t you think how young you are, and why should you die now? … Don’t you think several people whispered this to him? Don’t you think many advised him to pretend that he worshiped idols in order to save his life? Or told him to flee while the emperor still had not arrived? He could have done a lot of things, but he didn’t want to.

And we see how he died, and this gesture of his clearly shows us that he didn’t think about himself, didn’t cherish himself, didn’t love himself, didn’t cry out of self-pity, but loved Christ, and the wounds of Christ caused him more pain than his own, and not necessarily the visible wounds of Christ, but moreso the invisible wounds and sorrow of God at seeing the fear, the haste with which everyone fell away, the cowardice of man—the sorrow of God, Who laid down His life for man, fully trusting him.

And what did He, Who as if gave man carte blanche, receive in return? He gives you everything beforehand, He loves you even before you realize that He loves you. But man, despite this, retreats and runs away, man, despite this, finds a justification for himself to stand back and not confess Him.

But St. Demetrios was not one of these. St. Demetrios was one of those who are pained by this sorrow of God, at the site of this pain of God, more than His physical pain on the Cross. And he desired to die just as Christ died, as if to say: “Let my pain at least a little bit ease the pain of God”—that pain which is unending.

Christ experienced the pain of man’s renunciation of God not only then when He said: My soul is exceeding sorrowful.[3] He says it not only then. He says it even now, seeing the petrification and fear and flight of man. To see man, to whom He appeared every day, conversed with every day in silent prayer, helped every day, comforted every day by His blessings—and to see him now easily disavowing Him and the Church, and barring God from his heart, and indifferently passing by in silence or disowning Christ in word—this is the sorrow and pain of God.

The fathers spoke about it and they said that the love of God walks wounded through the world, finding no rest for itself, for there is no one who would respond to it. It is the wounded love of God, a grieving love, because love can’t be just from one side—it demands an answer from the other side. But man doesn’t hurry to give an answer; man’s answer is elusive. It’s as if you told your loved one that you are attached to him with all your soul, you love him, that he is your friend, but he answers: “Um, yeah, me too…” His answer—is pain, pain for him who would lay down his lie for his friend. Such is our Christian answer. It’s quite evasive, quite timid, standing with its feet in two camps, always ready to drop everything and run away.

St. Demetrios was not this way. His life clearly shows this, but his death as well. Such a death, in which everything, right down to his last movement, is done before Christ, before God, indicates that God was ceaselessly in his heart; it means that in his heart he unceasingly thought about Him; it means that his heart was in love with God and loved His every movement. Every movement and everything that happened with God were for him pain and joy—they were for him everything.

And therefore, I think, God was able to act through him. Therefore God so loved him. Therefore to this day so many miracles have been performed at his grave, near his sacred bones. Therefore we now say about him (for those placing all their hope in God will never die): he that believeth in Me shall never die, but is passed from death to life.[4]

He passed from death to life, and we will remember this both in this age and in the age to come. And we can say the same as Caesar, being thirty-five or forty years old and speaking with human reasoning, said to the statue of Alexander the Great: “At twenty-five years old you conquered the whole world, but I, at forty, have done nothing…”

It is all the more befitting for us to say at the icon of St. Demetrios: “At twenty-one years old you so loved Christ, but we…” But, having grown old in our wickedness, we are unable to say this, from year to year, from minute to minute, not adding good to good, but often evil to evil.

May God help and strengthen us.