Kiev boasts a wealth of wonderful ancient monasteries, yet the most mysterious of them is the Zverinets Monastery of the Archangel Michael of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (the UOC-MP), located in the capital’s Pechersky district, to the south of the Kiev Caves Lavra.

Archimandrite Leonty (Zolotarev), assistant of abbot of this marvelous monastery, has acquainted me with it.

The monastery derives its Russian name (“Zverinetsky”) from either the word “zveri” (meaning “animals”) or “zverinets” (meaning “a menagerie”). According to one version, the place was named after the local animal hunting that was once very popular in the thick forests of the area, which had a great variety of animals centuries ago. The “Tale of Bygone Years” [composed in the twelfth century by Monk Nestor in Kiev] reads: “There were a great forest and pine woods near the city [that is, Kiev], and people would hunt beasts there.”

Elena Anatolyevna Vorontsova, doctoral candidate in Historical Sciences, who for many years was head of the “Underground Kiev” department of the Kiev History Museum, suggested, “According to another version, the name had to do with a local menagerie at which animals and birds were kept and specially trained for hunting.”

The most mysterious and enigmatic monastery

Ivan Mikhailovich Kamanin (1850-1921), a historian, paleographer, archivist and author of the first research study of the Zverinets Caves, in his book entitled The Zverinets Caves in Kiev. Their Antiquity and Holiness, published at the printing office of the Kiev Caves Lavra back in 1914, wrote that all the earliest Kiev monasteries were under the ground and only later “rose up to the surface”.

Over the centuries, all of them were subject to alterations: they were reconstructed, remodeled, renewed; and only the Zverinets Caves, untouched beneath the ground for many years, remain absolutely intact and show us how these most ancient underground cells, which were used by zealous brethren of old times, really looked.

The fact is that the earliest Zverinets Monastery, founded during the first century of Christianity in Russia (Rus’), was covered up with earth in the troubled period of attacks by the Polovtsians and Mongol-Tatars, and forgotten for 800 years.

The mysteries of this monastery are yet to be unraveled by pioneers and discoverers—its caves’ total length exceeds that of the Near and the Far Caves of the great Kiev Caves Lavra; moreover, it has at least roughly a kilometer (c. 0.62 miles) of passages which are still unknown and unexplored.

How the underground monastery was discovered

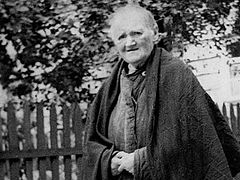

Theodosia Vasilyevna Matvienko. She was the first to show the location of the Zverinets Caves following a miraculous vision.

Theodosia Vasilyevna Matvienko. She was the first to show the location of the Zverinets Caves following a miraculous vision. On the same day, at noon, her neighbor, the artist Dmitry Zaichenko, and his friend, on their way from the neighboring Holy Trinity Monastery of St. Jonas, came up to the exposed hole after the landslide with candles in their hands. They cleared the opening and went down into the hole. And there they discovered a long cave with numerous human skeletons along with monastic cells.

The saints and ascetics of the Zverinets Caves

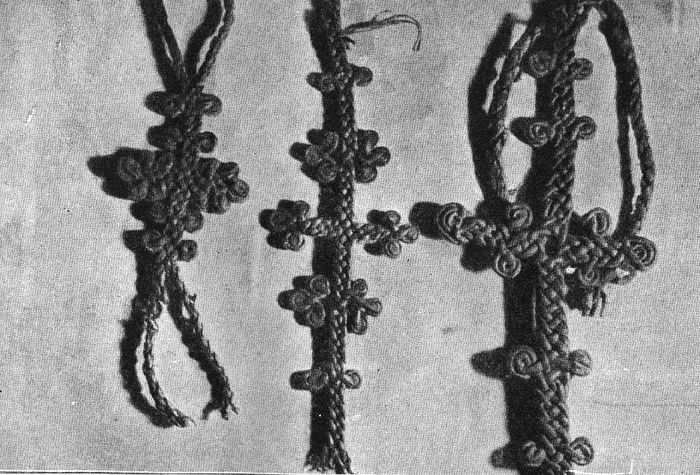

Undoubtedly, the people who rested in the caves were monks: their leather monastic belts depicting the Twelve Major Feasts, prayer ropes, monastic paramans woven from fine threads, half-decayed leather and felt shoes, wooden boards of old coffins (some of them were of cypress and still had their peculiar odor), fragments of millstones for grinding grain—all of them survived the corruption of time.

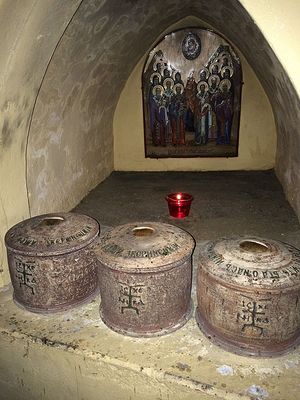

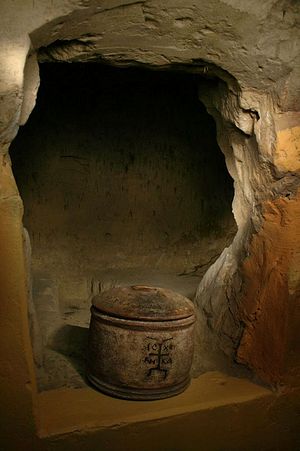

This is how Ivan Mikhailovich Kamanin who explored the caves described the cells of hermits in the Zverinets Caves: “Inside, the hermits’ cells are in the form of a large Russian cooking stove. Their length was equal to human height. A man could squeeze into it through its opening—sometimes easily, sometimes with effort. In the middle of the floor of the cell a hollow was dug knee-deep the full length. There were two benches for lying down on either side of the cell parallel to the hollow. On getting into this cell an ascetic could easily sit on one of the benches with his feet down in the hollow. Standing in the bottom of the hollow, a recluse could rise to his full height. Icons, icon lamps, holy books, vessels for holy water and prosphora could be placed on the opposite bench. The hollow could serve a recluse as a bed in his lifetime and as a grave after his death… The closeness of these cells to the altar enabled the hermits to listen to church services.”

The spiritual writer Evgeny Nikolaevich Pogozhev (who wrote under the pen-name, Poselyanin; 1870-1931) wrote in connection with the discovery of the Zverinets Caves: “There are no words to describe this sense of peace and the absolutely unknown feelings and emotions you are seized with in these caves, inside this diminutive simple church, in complete isolation from the world, amidst the silent remains of the brethren of an unknown monastery!”

Ivan Mikhailovich Kamanin admired the nature around the cave monastery: “The nature around the caves is truly delightful. Standing on the top of this high hill [within which this cave system is hidden], which is still uninhabited and open from all sides, with the blue sky above, and admiring these stunning, beautiful landscapes, you cannot help but feel a closeness to God and are filled with sublime emotion; dispirited by the hustle-bustle of city life, your soul feels relieved and free from the worldly cares, even if it’s just for an hour! What glorious nature!”

A request for prayer

Thirty years later, already aged eighty, Theodosia Vasilyevna Matvienko related to Kamanin how she had gone down to the caves, together with her acquaintance, so that she would not feel so scared. She had seen around fifty decomposed coffins in the small caves, and there were two skeletons with their heads to the opening (the entrance) in each cave. The observant woman counted a total of ninety-nine skulls.

Apart from the monastery’s brethren buried in the cave cells, remains of secular people were also found; they had apparently hidden from their enemies and died in the caves. Their skeletons lay in random positions along the main entrance, which indicates that the funeral rites had never been performed over them.

According to Theodosia Vasylievna’s account, the deceased dwellers of the caves appeared to her in dreams many times and asked her “to feed” them. The pious woman understood exactly what they meant and at once ordered a memorial service at the St. Jonas Monastery for the repose of those who had perished in the cave. After that the apparitions ceased.

“Left to themselves”

On the same day that the caves were discovered, the brethren of the neighboring Holy Trinity Monastery of St. Jonas towards the evening took candles and went to look at the cave monastery. The brethren took some of the finds with them for prayerful remembrance, and that was good, because many “curious folk” immediately thronged to the caves.

Soon the news of the newly-discovered unique monastery spread far and wide, but, unfortunately, it took time for people to realize the great value of this find—its spiritual, cultural and historical importance.

As many as thirty years passed from the moment of the discovery of the caves in 1882 till the beginning of their excavation and investigation, undertaken in late 1912. Over that period the wonderful caves, full of various relics, were not protected, they were “left to themselves” (according to Ivan Mikhailovich Kamanin), and the locals along with visitors from far regions could have stolen many of their precious holy objects.

The ancient monastery’s ascetic and patron

In 1911, new landslides took place exposing two new entrances to the caves. But now the cave monastery had its protector—the confessor of the Holy Trinity Monastery of St. Jonas Igumen Valentin (Korotenko). The Lord revealed the spiritual significance of the caves to him, and Fr. Valentin moved from his “cozy” monastic cell to a hastily built simple board shack in order to guard the cave cells and perform memorial services.

It is hard to imagine the privation and hardships the ascetic had to suffer—cold and scorching heat, threats from treasure hunters and thieves, intrusions of the curious. Nevertheless, most of the pilgrims began to come here in order to pray and sense the grace of the ancient holy site. Thus a skete in the Zverinets Caves came into existence.

He suddenly felt a clear inner command

We light candles and go down into the caves. Our hearts beat faster—this site is filled with the grace of God. Fr. Leonty recounts: “On the feast of the Kazan icon of the Mother of God, October 22, 1911, the new patron of the Zverinets Caves appeared—it was Prince Vladimir Davidovich Zhevakhov. It is known from his diary that in the morning he woke up earlier than usual and suddenly felt an inner command that he must go for the service to the Holy Trinity-St. Jonas Monastery where he had never been before.

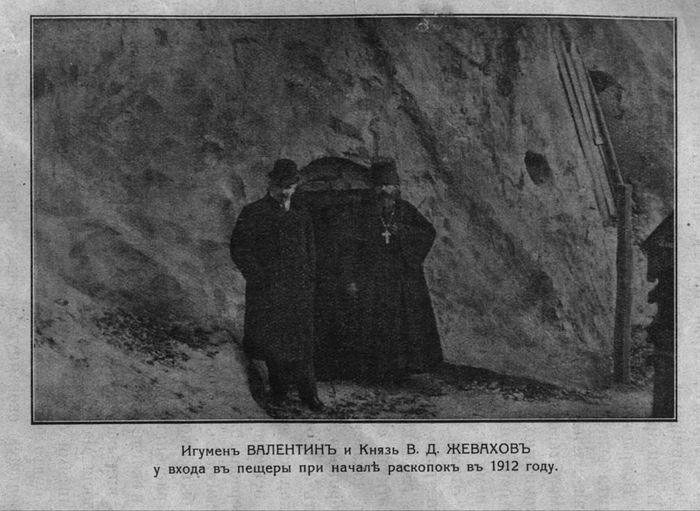

Igumen Valentin and Prince Zhevakhov at the entrance to the caves at the beginning of the excavation work in 1912.

Igumen Valentin and Prince Zhevakhov at the entrance to the caves at the beginning of the excavation work in 1912.

After the Liturgy the prince joined the crowd of pilgrims and decided to look at the then little-known and half-buried caves. After the prayer service and the memorial service, Fr. Valentin brought the prince close to the cave openings, saying: ‘Your Excellency, it would be good to restore a monastery on this ancient holy site.’ And the Almighty through these two men revived monastic life in the Zverinets Caves; although it was not for long.”

If you once visit the Zverinets Caves, you will want to come here again and again

The caves make a strong impression on those who visit them: people want to come back here again and again.

It is interesting that Ivan Mikhailovich Kamanin who investigated these caves physically remained inside them after his repose: at to his own request, he was laid to rest here at the end of Altar Street.

Another man whose remains have rested here at his own will is Igumen Valentin (Korotenko) who died during Great Lent, March 10, 1917. The ascetic was interred in the caves not far from the entrance. The ascetic labors that Fr. Valentin performed for many years were appreciated by the venerable fathers of Zverinets and, in some sense, he became one of them.

Prince Vladimir Davidovich Zhevakhov was so fascinated by the Zverinets Caves that he couldn’t leave them.

How Prince Vladimir Zhevakhov became the meek Monk Joasaph

The prince became the caves’ benefactor and patron and a churchwarden of the church above the caves. It was with his funds that the land above the caves was taken on lease and archeological excavations were carried out. Thanks to his patronage, theft of the caves’ relics was brought to a halt.

Later, over the period of the Revolution and the Civil War, Prince Vladimir Davidovich Zhevakhov together with his twin brother Nicholas hid from the Bolsheviks in these caves and labored as hard as any of the skete monks.

It was perhaps through the prayers of the Zverinets saints of the old times that a brilliant lawyer, honorary justice of the peace and Senior Adviser of the Kiev Governorate Administration Prince Zhevakhov received his monastic tonsure in these caves and became the meek Monk Joasaph—he was given this monastic name in honor of his ancestor, St. Joasaph of Belgorod. Monk Joasaph (Zhevakhov) was ordained a hierodeacon, then a hieromonk, and, lastly, consecrated a bishop.

Then the Solovki Special Purpose Camp, exile, new arrests, and, lastly, martyrdom awaited Bishop Joasaph: on December 4, 1937, the feast of the Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple, he was executed by firing squad near Kursk.

In 2002, the benefactor of the Zverinets Caves, Bishop Joasaph (Zhevakhov) of Mohilev was canonized as a hieromartyr. He is still spiritually present at his beloved Zverinets Monastery: his icon is kept at the Cathedral of the icon of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow”, in its lower church, dedicated to the Holy Hierarch Joasaph of Belgorod and the New Martyr Joasaph of Mohilev.

A catastrophe

Elena Anatolyevna Vorontsova, former head of the “Underground Kiev” department of the Kiev History Museum, wrote: “On June 6, 1918, one of the most terrible tragedies happened in Kiev. Between ten in the morning and noon there were five explosions at the ammunition depots at Zverinets behind the Bratskoye Cemetery. In addition to much destruction and many fires caused by the explosions, two new holes appeared. One of them was close to the Zverinets Caves, the other one—at the opposite end of the plateau, namely beside the so-called Steward’s Gate of the Holy Trinity Monastery. These holes clearly indicated the existence of underground tunnels within the area. The church above the caves was seriously damaged by the explosion. The roof along with the ceiling on the first floor collapsed; icons, the iconostasis, decorations and church furnishings were damaged. The explosion also affected some segments of the caves.”

Shortly before its closure, the Zverinets Skete had about forty monks. In 1933, godless people murdered the abbot of the skete, Archimandrite Philaret (Kochubey), and a year later the skete was dissolved and the church blown up.

The post-war period

Elena Anatolyevna Vorontsova related: “In the post-war period, private residential houses were built in the Zverinets district, and the caves were forgotten for a long time. People finally remembered them in 1964, but the openings were covered with earth. Cavers were aware of an approximate site of one of the entrances on the territory of a private mansion in Michurin Street, but the owners had installed a toilet cubicle there. It was moved and only then did it become possible to go down into the caves and to carry out archeological prospecting. The cave labyrinth turned out to be partly blocked, and the specialists couldn’t reach its end.”

In 1969, by decree of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Zverinets Caves were designated as an archeological monument. Due to this the construction of a multistoried building was cancelled here in 1988, and so the Kiev History Museum has been in charge of these caves.

Fr. Leonty’s story about the icon of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow”

“In June 1918, as a result of sabotage, military depots of the Zverinets fort were blown up, and the explosion wave destroyed the wooden Church of the Nativity of Holy Theotokos above the caves. Soon the temple was restored with the funds of the faithful and consecrated in honor of the icon of the Virgin Mary ‘Joy of All Who Sorrow’.”

After the closure of the monastery in the 1930s the church’s icon was considered lost.

In 1997, a skete of the Zverinets Caves was re-founded. In 2009, on the foundation of the skete, the Monastery of the Archangel Michael was established.

“In 2010, a collector approached the monastery’s father-superior and asked him if he was interested in purchasing a relic associated with our monastery. It turned out to be our church’s icon ‘Joy of All Who Sorrow’. On the eve of Holy Friday, 2010, the icon returned to the monastery and now its largest cathedral is dedicated to the icon of the Mother of God ‘Joy of All Who Sorrow’.”

Fr. Leonty’s story about the Zverinets icon of the Mother of God

“The Zverinets icon of the Mother of God was uncovered when the grave of Abbot Clement of the Zverinets Monastery was dug up in 1913. The icon painted on an enameled iron plate had miraculously survived in the caves’ microclimate with ninety-five to ninety-eight percent humidity! From 1915 on, this icon was adorned with a precious mounting (as it was specially venerated) with the funds of the skete’s benefactor—Prince Vladimir Zhevakhov. When the monastery was closed, the mounting was removed from the original icon, and both relics were most probably given to some faithful parishioners for safekeeping.

“After the war a silver mounting with the inscription ‘The Zverinets Icon of the Mother of God’ came into the possession of Mitred Archpriest Michael Makeyev, who at his Church of the Greatmartyr George the Victorious of the Selishchi village (the Baryshivka district of the Kiev region) preserved a great many relics from monasteries, convents and churches desecrated by atheists in the Soviet era. In 2000 he learned about the Zverinets Monastery from the St. Jonas Monastery’s newsletter and returned our relic to us. This event took place on the feast of the Iveron icon of the Mother of God, October 26.”

The monastery today

Daily services are held at the monastery both in the caves and at the above-ground churches. At present there are three churches here:

1. The cave Church in honor of the Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Colossae.

2. The Church in honor of the Synaxis of the Venerable Fathers of the Zverinets Monastery, built between 2007 and 2010 above the entrance to the caves in the Byzantine style. Its architecture bears resemblance to churches on Mt. Athos.

3. The Cathedral in honor of the icon of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow” in the style of ancient Russian architecture, with its lower church consecrated in honor of the Holy Hierarch Joasaph of Belgorod and the New Martyr Joasaph of Mohilev in 2013.

At the present time, twelve monks live at the monastery, and they have different types of obediences: cleaning the territory of the monastery and tidying up the church; work in the greenhouses and the kitchen-garden, kitchen and refectory; and other obediences that are common at all monasteries.

The Docheiariou Monastery of the Holy Archangels Michael and Gabriel on Mt. Athos gave the Zverinets Monastery of the Archangel Michael a replica of the miracle-working icon “Quick to Hear”. Now the iconographic depiction of this event (significant for the Zverinets Monastery) is kept at the church with the miraculous icon.

The monastery’s official website: http://zvcaves.com.ua/

Archimandrite Leonty speaking about the caves.

Painting of the Zverinets Monastery’s cathedral.