Count George Alexandrovich Sheremetev saw Russia for the first time in his life in 2001 at the age of fifty-six. He was among the children of the Russian White emigrants who were born abroad. His life as well as those of his close relatives were full of persecutions and sorrows, wanderings across three continents and foreign countries, among people of various ethnic origins and religious traditions.

Yet in all these wanderings and travels George Alexandrovich and his family have remained faithful to the Orthodox faith, kept their native Russian language, love for their motherland, honored the memory of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers, the New Martyrs and all the victims of the atheist regime, and have always prayed for Orthodox Russia and the Russian nation. Count Sheremetev has shared some of the stories of his life with Pravoslavie.ru regular contributor Olga Rozhneva.

“God preserves everything”

My ancestors made efforts to serve their fatherland. Not only did the Sheremetevs own their patrimonial ancestral lands, they also did charity work, built hospitals and almshouses. The motto of the noble Sheremetev family was the following: “God preserves everything.”

My great-grandfather, Count Alexander Dmitrievich Sheremetev, was born in 1859 in St. Petersburg, was a composer, Flugel-Adjutant of Emperor Nicholas II, and a famous philanthropist. He passed away in 1931 in Paris.

My grandfather, Count George Alexandrovich Sheremetev, was born in St. Petersburg in 1887. He studied at History, Language and Literature Department of the St. Petersburg University and then served in the Horse-Guards Regiment, which was under the patronage of Empress Consort Maria Feodorovna. Subsequently my grandfather visited her in Denmark where she had emigrated following the Russian Revolution.

I am my grandfather’s namesake, because it is our family tradition to name our oldest sons after their grandfathers. I have a grandson who was also given the name George, after me.

In 1910, my grandfather, a twenty-three-year-old valiant officer, married Her Serene Highness Princess Ekaterina Dmitrievna Golitsyn. In 1911, his first son (my father) was born; of course, they gave him the name Alexander.

Spiritual testament

My grandfather’s “spiritual testament” reflects the principles by which he was guided in bringing up his little Alexander. Although my grandad wrote it down in mature age, he collected his reflections that spanned many years from his youth. This is how my grandfather, Count Sheremetev, exhorted his son in this testament: “Remember that nobleness of soul is the only genuine nobleness in life. A noble name and title that you were born with don’t automatically make you noble. Rather, they impose an obligation on you, namely to maintain the good name of your ancestors by all your deeds. A scoundrel is always mean, but if he also bears a noble name, it is truly abominable. Noble is he whose deeds are noble regardless of his name. Get rid of all dirty, dark thoughts that lead to temptation. I will repeat over and over again: Don’t allow yourself to fall for bad, disgusting thoughts; otherwise they will gradually become a habit with you and evil thoughts will turn into evil deeds. All kinds of dirty, dark, obscene thoughts, even if they are not put into action, inevitably lead to ailments and failures in our lives because they separate us from God. God is perfect. When we move towards God, we try to become perfect. However, there are many various kinds of perfection depending on our intentions. You can strive to become better than others, and you can strive to become better for others’ sake. The former is for self-glory, whereas the latter is for the glory of God.

“Be generous just as God pours out great blessings onto people with His generous Hand. Almsgiving is a great virtue and it protects the lives of people. Forgive those whom have personally hurt you and wronged you, and do good for them. But in forgiving personal wrongs, you should be determined to struggle against those who offend the weak and destroy holy churches. You need to bear in mind that you must forgive and forget only personal offences, while you have no right to tolerate crimes committed against others; rather, you should struggle against offenders. The Church fathers say: ‘Divine protection is with him who defends the offended.’ Love God and others, and endure their shortcomings as you are imperfect yourself; don’t be lazy about reading the morning and evening prayers every day; set your hopes on God alone, don’t brag about anything, and, most importantly, avoid pride, for it is the source of all the vices.”

My grandfather also wrote the following about happiness on earth:

“You were born not only to live in this world and enjoy your life. You should also help those whose lives are hard. The more consolation and joy you give to others the happier your life is. The supreme happiness in this world is in loving and serving others.”

For faith, tsar and fatherland

But my grandparents’ happy life was overshadowed by the terrible First World War, in which the total number of military and civilian casualties exceeded that of any conflict previous to it. Count George Sheremetev went through the war with the rank of rotmeister (captain) of his regiment, defending “faith, tsar, and fatherland”. They fought until the Revolution. As soon as his Horse-Guards Regiment’s squadron was revived in the Crimea, he returned to his unit and fought in the volunteer army until its evacuation from the Crimea. In the 1920s he served as secretary of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich. My granfather reunited with his wife and son abroad. Ekaterina Dmitrievna reposed in in the Lord in 1936.

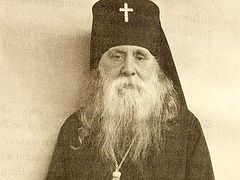

During the Second World War, as a Russian man my grandfather was interned and ended up at a displaced persons’ camp near Hamburg. In 1950, he was ordained and several years later he served in the ROCOR jurisdiction in London, and became the spiritual father of the future Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) from the Patriarchate of Constantinople’s jurisdiction. He also was rector of the church of the Annunciation Convent in London1, which had been founded in 1954 with the blessing of St. John of Shanghai. My grandfather reposed in the Lord in London in 1971.

Abbess Elizabeth’s reminiscences of my grandfather

This is what Abbess Elizabeth (Ampenova; 1908-1999) of the Annunciation Convent in London, who remembered my grandfather with great fondness, wrote about him: “The way he treated others and his method of approaching their souls earned him the love of officers and lower army ranks alike… His living faith in God, deep love for his motherland, loyalty to his sovereign, confidence in the future resurrection of Holy Rus’, a phenomenal knowledge of national history along with both Russian and European literature made him an interesting companion from whom you could learn very much.

“He combined the nobleness of his ancient family with amazing modesty and an almost childlike simplicity. He would show me his diaries where he had made his notes from his youth (and later as a vivacious, brilliant officer) about the things that interested him and touched his heart. Already in that early stage he made notes from the Philokalia on prayer and spiritual perfection…

“Fr. George loved to pray, and had an ability to pray fervently with a sincere, warm heart. Always amiable, endearing, attentive, and cheerful, he would support, comfort us, and when necessary, edify us with a strict instruction.

“An unmercenary, Fr. George could easily give his last penny to someone in need. Despite his aristocratic origin he was very meek and a model of modesty and Christian love for all of us…

“There was such zeal, such fervor in his prayers! His commemoration book contained a long list with hundreds and hundreds of names of the living, sick, suffering, persecuted, exiled, and departed, beginning with tsars, soldiers, clergy, all those martyred by the atheist government, his friends, relatives and those whom he had buried and over whom had performed funeral services in absentia…

“In the final years of his life Fr. George used to repeat that he was very old and weary, yet we couldn’t believe that his end was near. He was relieved by the fact that in spite of his physical weakness he was still able to take care of himself and was not a burden to anybody else. He would say to me: ‘Mother, it is not death but dying that is frightened and difficult to endure!’

“And the Lord took his soul quickly and without pain on the feast of Mid-Pentecost as a sign that his life on earth had become full. The ninth day after his death coincided with the feast of the commemoration of the Appearance of the Sign of the Precious Cross over Jerusalem, signifying that he had borne his cross honestly and righteously till his death. Remarkably, the fortieth day after his repose coincided with the Synaxis of All the Saints of the Russian Lands.”

My parents

My father, Alexander Georgievich, emigrated as a boy of ten. He studied in France and then got a job at a metallurgical company, and worked as a translator—he knew as many as seven foreign languages. My dad fought with the French Army against the Nazi Germany, was taken prisoner and sent to a forced labor camp.

My mother, Marina Iosifovna Mamatsishvili, was Georgian by birth but recieved a Russian upbringing, because her stepfather was the Russian Count Alexander Illarionovich Vorontsov-Dashkov, Flugel-Adjutant of Emperor Nicholas II, and a member of the White movement.

My mother’s parents fought in the First World War and spent the first year of their marriage (1916) in the “army in the field”, where my grandmother Anna Ilyinichna (nee Princess Chavchavadze) was a hospital nurse. Some space within their house (as was the case with other mansions of the Vorontsov-Dashkov family) was used as an infirmary where the wounded would receive treatment.

Following the Revolution Alexander Illarionovich fought in the volunteer army, while his spouse Anna Ilyinichna with children (including my mother) went into hiding to avoid arrest and execution by firing squad. In her memoirs, my grandmother Anna Ilyinichna noted: “It is impossible to write about all these horrors in detail, with so much blood and suffering, so many tears all around!”

“You can kill us if you want, but let the children go!”

My mother recalled how their family was arrested and led to a firing squad: grandmother Anna Ilyinichna (then a very young woman), my mother (then a little girl), her sister Vera, infant brother Illarion and the nanny. The nanny addressed one of the soldiers: “Have a heart! What are you doing? There are children among us! Let them go! You can kill us if you want, but let the children go!”

One of the Red Army officers gazed at her and commanded: “Go away! Immediately! Don’t let me catch you here again!”

And my granny with the nanny and children managed to lose themselves in the crowd and then hid at their friends’. That saved their lives. On the following day the soldiers came to arrest them for the second time, but the servant answered that all of them had been arrested the day before. Then the soldiers in their fury sacked the house and left.

Wanderings across countries and continents

I was born in 1945 and naturally was named George for my grandfather. After the war there was havoc and ruin in Europe, so in 1948 my father took his wife and children to South America. Thus I was born in France and as a three-year-old child ended up in South America.

We first sailed to Brazil and then moved to Argentina. We took up our residence in Buenos Aires, the country’s biggest port city with its European-style architecture and buildings. My father worked there as secretary of the director of the metallurgical works and as a translator in the same field.

The weather in Buenos Aires often seemed unpredictable to us, with temperature jumps from +5 to +20 degrees Celsius in winter, strong winds, summer heat, and high humidity. The climate of South American countries is sometimes unbearable for Europeans.

In the 1950s, economic and financial crises were sweeping over the country. Everybody still hoped that the former “golden age” of Argentina would return soon; before the First World War Argentina had been one of the wealthiest and most prosperous countries in the world. Its per capita income could be compared with that of France and Germany and was much higher than in Italy and Spain. But as years went by things took a turn for the worse, which affected the lives of both the natives and emigrants.

Wanderings again

My dad started looking for ways to take his family to the USA and he eventually succeeded. At the age of eighteen I ended up in another foreign country. I could speak Russian and Spanish and now had to learn English into the bargain.

It was difficult for me to radically change my life and circle of acquaintances. But those wanderings enabled me to get to know the cultures of other countries, the worldviews and mentalities of people of different nationalities. Now besides my native Russian I know English, Spanish and French.

In the USA we first settled in Los Angeles, and later I moved to New York City to get my education. My parents moved from Los Angeles to Sacramento, the capital city of California, in 1973. Mother fell asleep in the Lord in 1991, and father reposed in San Francisco in 1996.

I graduated in communications. I work for a company specializing in multilingual tourism and international technical visits.

On how we have kept the Russian language alive

I was born in France, grew up in Argentina, and live in the USA, yet my blood is Russian and my feelings are also Russian. Our parents cultivated the love for and a sense of belonging to the Russian nation, culture and history in their children.

It was forbidden to speak languages other than Russian at home. We always felt that we were Russian and we considered it our duty to preserve the heritage passed down to us from our fathers and forefathers. True, if you are young and live in a foreign society you willy-nilly habituate yourself to the norms of local culture, yet your roots remain intact.

It was a strict rule that our parents set out: Once we went outside we were to speak the language of the country we lived in, while at home it was our sacred duty to speak in our native tongue. I have two daughters and two sons—Alexander is the elder one and Nikolai is the younger. And I maintain my native language, encourage my children to do the same and hope that they will teach their children (that is, my grandchildren) the same values.

Maria Nikolaevna

My wife Maria Nikolaevna comes from the noble Revutsky family from the former Kherson province. She was born in Brussels, Belgium, where her family had emigrated after the Revolution. Sometimes she recalls her father’s stories, according to which his parents were sent to the “chrezvychaika” [most probably a secret prison], sentenced to death, and he contrived to give them food through the prison window. By a miracle her grandparents survived, although they went through a great deal of sorrow.

The Revutsky family immigrated to the USA in 1951. It was here that Maria Nikolaevna and I met and married. She graduated in art history, became a professor of Art History at the University of San Francisco, and honorary member of San Francisco Art Museum. Her Ph.D thesis was devoted to Byzantine art and the development of the iconostasis in Russia.

Russia’s spiritual power

In 1982, during her studies in London Maria Nikolaevna (while working on her thesis) made a trip to Russia, where she visited many churches, including the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, and sensed the great spiritual power of Russia, which was evident despite the difficult circumstances the country lived in.

The father-confessor of my spouse and her family was Vicar Bishop Nektary (Kontsevich; +1983) of Western America, a spiritual child of the Holy Elder Nektary of Optina (+1928) and a close friend of St. John of Shanghai. Bishop Nektary would tell the Revutsky family about Optina Monastery so vividly that all of them came to love it.

Bishop Nektary would perform memorial services for the repose of the Royal Martyrs [before their canonization in 1981] and gave talks on their importance for Russia. It was at his insistence that the Royal Martyrs were canonized by the ROCOR in 1981, nineteen years before their canonization by the Moscow Patriarchate.

I met Bishop Nektary through my wife when he was a frail old man. But in spite of his feebleness everybody sensed his spiritual strength.

St. John of Shanghai, Wonderworker of San Francisco

We are now talking at the Old Russian Cathedral where the pillar of the ROCOR, St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco (+1966), served. The cathedral’s dean, Fr. James (Corazza), has celebrated a prayer service in front of the icon of the holy hierarch and we have just venerated his mantia (monastic mantle) that is kept here. And it is very symbolic as St. John of Shanghai plays a key role in our family’s spiritual life.

My wife Maria Nikolaevna and her family knew St. John of Shanghai when they lived in Belgium. She recalled how Archbishop John used to serve. He was anything but tall, yet everyone was amazed by his spiritual strength and felt the grace of the Holy Spirit when he served. Whenever the saint blessed his parishioners with his cross, he would make a sign of the cross at full height, right to the floor, with an unshakeable faith in the all-triumphant power of the cross.

Although I saw Archbishop John only once, after our move to San Francisco in 1965, we still attend both this old cathedral (where he used to serve) and the new cathedral in honor of the “Joy of All Who Sorrow” icon of the Mother of God, which was completed through his tireless labors one year before his repose. The relics of this marvelous wonderworker and man of prayer are kept at that new cathedral.

Our fathers-confessors were saintly men

All our family members are very religious people and the life of our family has always been closely connected to the Church. My grandfather was a priest, and my parents always sang in the church choir. Our fathers-confessors were saintly men. And I have been actively involved in the Church life since my childhood.

My first spiritual father, Archpriest John Gramolin, rector of the Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh in Buenos Aires, heard my first confession when I was seven and he was about 100. The confession lasted half an hour, Fr. John explained many things to me in detail and instructed me.

This spiritual elder and mitered archpriest spent the final years of his life at a Russian nursing home in Buenos Aires, and it was after his repose that the administration saw his real documents. It turned out that Fr. John pretended to be ten years younger than he really was in order to get an entry permit, because many countries denied entry visas to elderly people. Thus, according to the Argentinian documents he was 101 years old, whereas according to the Russian documents he was 110. When I was under this elder’s (who was born in 1857) spiritual guidance, it was a living and direct link to the mid-nineteenth century!

My next father-confessor was Archimandrite Sava (Saracevic) who was a Serb. Later he was transferred as a vicar bishop to Canada to serve in the Diocese of Edmonton. His erudition, the gift of spiritual speech and zeal in his ministry made him an outstanding hierarch.

Bishop Sava called on everyone to pray hard for Russia. He deeply venerated St. John of Shanghai, and supported him when the saint was slandered and underwent a judicial trial, although the court eventually acquitted him. After St. John’s blessed repose, Bishop Sava wrote a series of articles about him, collected materials on his life, and testimonies of his miracles, which greatly contributed to the holy hierarch’s canonization in 1994.

Optina Monastery and affinity of souls

My wife and I travelled together to Russia in 2001; it was then that I first stepped foot onto Russian soil. Of course, we went to Optina Monastery and, providentially, the first man we met at Optina was Igumen Tikhon (Borisov), the abbot of the skete; we at once experienced an “affinity of souls”, a spiritual bond with him. From that moment Optina Monastery became a sort of a spiritual haven for us—here we receive Divine grace and try to retain it in our souls.

Evacuation rather than emigration

Nowadays Russians coming to America as emigrants generally seek a better quality of life and hope to find an “earthly Paradise” there. However, as for our families, it was evacuation rather than emigration. “Evacuation” would be a right word. “Emigration” and “evacuation”—these two words have very different meanings. Before our move to the USA we had been well off in Russia, but in America most of us lived in poverty and it was quite difficult for us to settle down and get accustomed to its mode of life.

Members of titled families, of the Russian aristocracy would wash floors in hospitals, work as taxi drivers, loaders and what not, but this by no means belittled their titles. True, we strove to improve our quality of life, but it wasn’t our primary aim. Our goal was to return to Russia one day. We “lived in our boxes”, as it were. We did until recently, waiting for the right time to come back to the motherland.

Now it is probably too late for people of my generation to do it—life is coming to an end… But we do keep up-to-date with all current news and developments in Russia with great concern…

The unfading light

This is what my grandfather, Archpriest George Sheremetev, wrote about the autumn of life: “One shouldn’t be afraid of old age. True, at the beginning it can be very sad that you cannot do the things that previously were both physically and mentally easy. But if you find the strength to bow to the inevitable and accept the will of God Who created the inviolable physical laws, then you will feel relatively at ease. You don’t hurry to finish one or another work any more because the wisdom of old age has taught you that you can’t do everything at once. You retreat into yourself more often and devote more time to communication with your Creator…

“And you begin to feel peace in your soul. Little by little it loses touch with the cares and chores of this life, beholds the unfading light, and gives praise and thanks to God. These peaceful minutes are much more inspiring than the outbursts of joy and impulses of your heart in your young age, which were good in your day as well.

“Spring flowers are lovely and beautiful. Yet the sad, silent melody of falling leaves in autumn is blessed, too. They humbly lie on the ground, unite with it, providing living juices for spring flowers. And their quiet dream ascends to God like a silent prayer that blesses this thoughtful beauty of the autumn forest. For the Almighty does not forget a single blade of grass. This quiet prayer rings for spiritual ears, like a delicate harmony of nature that glorifies the Creator. It is called peace, and I am so sorry for those who don’t feel it.

“The evening has set in. You have worked through the day, poorly as it was. All the difficult tasks in your life are past. And your soul gives thanks to the Lord for giving it strength and help in your life path. A quiet sleep and peace until the Radiant Resurrection are at hand… And Blessed be the Name of the Lord from henceforth and for evermore (Ps. 112:2).”

And we cannot help but exclaim in response: “Amen!”