The following is the text of a talk by the author on Fr. Nicola Yanney on October 28, 2018, at a pilgrimage in Kearney, Nebraska, commemorating the 100th anniversary of his repose.

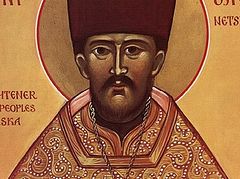

Photo: orthodoxhistory.org I think the first time I became aware of Fr. Nicola was when I read Bishop Basil’s enthronement address, in 2004. He talked about this circuit-riding priest who had a huge territory that basically covered the entire middle of the United States. It’s impressive, for sure—but really, I have to be honest, it doesn’t stand out. There were a LOT of circuit-riding Orthodox priests in those days. I wasn’t here for the diocesan pilgrimage ten years ago, but it struck me as a family honoring their forefather—totally appropriate, but not necessarily a big deal for anyone outside of the diocese. Fr. Nicola is the ancestor of the Diocese of Wichita, and he’s interesting to us because he’s OURS, but if you’re Greek or Russian or Serbian or you live on one of the coasts, Fr. Nicola is just another old priest. There were a lot of those guys.

Photo: orthodoxhistory.org I think the first time I became aware of Fr. Nicola was when I read Bishop Basil’s enthronement address, in 2004. He talked about this circuit-riding priest who had a huge territory that basically covered the entire middle of the United States. It’s impressive, for sure—but really, I have to be honest, it doesn’t stand out. There were a LOT of circuit-riding Orthodox priests in those days. I wasn’t here for the diocesan pilgrimage ten years ago, but it struck me as a family honoring their forefather—totally appropriate, but not necessarily a big deal for anyone outside of the diocese. Fr. Nicola is the ancestor of the Diocese of Wichita, and he’s interesting to us because he’s OURS, but if you’re Greek or Russian or Serbian or you live on one of the coasts, Fr. Nicola is just another old priest. There were a lot of those guys.

I am not here to talk about Fr. Nicola because he’s the forefather of the Diocese of Wichita, or because he was the first priest ordained by St. Raphael, or because he’s a somewhat notable historical figure in American Orthodoxy. Those things are all true, but they’re footnotes. The reason Fr. Nicola is important, the reason he warrants the attention, not just of Antiochians in Mid-America, but of all Orthodox Christians around the world, is because he is an icon of faithfulness, and endurance, and sacrifice for the sake of Christ. The legacy of Fr. Nicola is not merely this diocese; the legacy of Fr. Nicola is sanctity.

Fr. Nicola’s early biography is interesting but not necessarily uncommon. He grew up near the Balamand Monastery. He got married in his late teens, and he left his village to come to America, to try to make a life for his family that was better than what was available in Syria. In this, he was like so many others, including my own family, and many of yours. America was the land of opportunity, and seeking that opportunity meant leaving behind home and family and community.

He was just Nicola Yanney then, of course—not yet Father Nicola. He and his wife Martha went first to Omaha, and Nicola worked as a peddler—again, like a lot of young Syrian immigrants at the time. They had kids, and they moved to a little homestead not too far from Kearney, and they planted modest roots. I don’t know what their expectations were, or if they had expectations. I do know that they were pious Orthodox Christians who had gone years without even seeing a priest, much less confessing or taking communion or having their kids baptized.

And then one day, something unexpected happened. The year was 1899. Nicola and Martha had been in Nebraska for almost six years. A few years earlier, a dynamic young Syrian priest named Fr. Raphael Hawaweeny had come to New York to minister to the scattered Syrian Orthodox immigrants in America. And now, in the late summer of 1899, St. Raphael made it all the way to the remote town of Kearney, Nebraska… I’ll let St. Raphael himself tell the story, from his missionary journal:

“On Tuesday, September 7th, I departed Omaha and went further west to the city of Kearney, where I arrived after midnight instead of arriving at 3:30 PM as planned. […] When I arrived in Kearney almost all of our Syro-Arabs came to greet me at the station. From the train they took me to the house of their elder in an open carriage. It was so cold that I was shivering all the way and warmed up only at the fireplace in the house of my hosts, and paid for it with sniffles. We all stayed up until four in the morning, after which time everyone went home to get some rest. The next morning, I felt so bad that I wasn’t able to serve the Divine Liturgy, but only a Typica service.”

So, pausing there for just a moment—this account starts to tell you something about St. Raphael, and how devoted he was to his people. His train was delayed eight hours; he arrived, exhausted, after midnight; it was cold and he felt sick—and then he stayed up until four in the morning visiting with his people, and then, after barely a nap, he woke up in the morning for a church service, even though he felt so bad he couldn’t serve the Liturgy. Anyway, St. Raphael continues:

“In the evening, I felt better, and offered to the members of the local community to go on horses to the farm of one of the Orthodox Syro-Arabs who lives there with his family and brother, located about 18 miles to the northeast of Kearney. At 9 PM with 15 people with me on four horse-drawn carriages, we departed for our journey. The weather was beautiful, the road was even, and it was a full moon. My companions enjoyed it so much that the entire trip they were singing church and national songs.”

Okay, so St. Raphael, who was sleep-deprived and fighting a bad cold, heard about this farmer—Nicola Yanney—and his family, who were living way out in the country. And he volunteered to travel to them in the middle of the night. This was his own idea. This is the good shepherd who leaves the 99 sheep and seeks after the one who is lost. In this case, not lost spiritually—the Yanneys were spiritually quite strong—but literally lost in the wilderness. He could have sent some of the Kearney Syrians to go bring the Yanneys back to the city, but no—he went to them himself. That’s the kind of pastor St. Raphael was.

“We arrived at the house of our farmers at about one in the morning. From all the noises and firing from handguns of my companions, the farmers ran out from their house and learned that their priest has arrived, and they were so overjoyed that, with tears and thanksgiving, they embraced us and kissed the ground, my hands, and my feet, thanking the Lord God, who granted them to see an Orthodox priest after seven years without one. Truthfully, we all cried as well, seeing such joyous greetings from them. The wife of the farmer cried more than anyone from her joy. She was mourning so much that living in such a distant place, she was deprived of an ability to ever see an Orthodox priest who could confess and commune them, and most importantly, would baptize her four children, the oldest of which was six years old. Now her sorrow has turned to joy, and not believing her eyes, she continually crossed herself, raising her hands to heaven, thanking the Lord for this unexpected mercy.

“The home was very small. We all stayed in one room. From exhaustion, some started falling asleep on their chairs, others on the floor, and I was offered a small couch. In the morning everyone, with piety, attended the Matins service. After that, I served the Blessing of Waters and blessed the house and their entire farm. Having spent the entire day there, we returned to Kearney in the evening. The next day, this farmer, with his whole family and the brother, came to Divine Liturgy and for the baptism of their children…”

This was Nicola’s first encounter with St. Raphael, and more than that, it was his first encounter with a proper Orthodox missionary. He’d known priests and monks in Syria, but Raphael was something different—he was a pastor with a flock that wasn’t concentrated in a village, but was scattered across a continent. And Raphael’s devotion and self-sacrifice, to care for the most isolated of his people, left a deep impression on Nicola that became apparent during his own years as a missionary priest.

Eventually St. Raphael left, and life continued for the Yanneys. They had four little kids, and Martha was expecting their fifth. Nicola was 29 years old—five kids before the age of 30. And then something went wrong. Martha wasn’t well. She went into labor too early. There was no one to help, and even the best doctors at the time probably couldn’t have done anything. Martha died in childbirth. Nicola was a widower at 29, with five kids.

And then he watched, helplessly, as his newborn baby wasted away and died, too, just days later.

I know that infant death was much more common back then than it is now, and it was also a lot more common for women to die in childbirth. But that doesn’t take away from the agony Nicola and his surviving children experienced. As a husband and father—my own fifth child was just born in August—I feel a particular sorrow for Nicola. The pain of a loss like that never goes away.

But it’s what happened next, what Nicola did after being widowed, that really begins to set him apart. Before Nicola were at least two paths—one narrow and one broad. The broad path would have been remarriage, and you could hardly fault him for choosing that path. He had little kids who needed a mother. He was a young man, only 29 years old. He easily, easily could have justified mourning for a time and then finding a new wife among the many Syrian immigrants who were flooding into the United States, and even making their way as far as Nebraska.

The narrow path was kind of an unheard-of path. It wasn’t like the priesthood was a viable career option—we didn’t have seminaries at that point, and there wasn’t even an Antiochian bishop in America yet. Orthodoxy had barely begun to take root, and there was only a smattering of parishes in the whole country, of any ethnic background. But a little over a year after Martha’s death, the Orthodox Syrians in Kearney wanted a parish of their own, and they decided as a group that Nicola should be their priest. And he agreed to bear this cross. It meant that he would never remarry, and it also meant that he’d have to sacrifice time with his children for the sake of his priestly ministry. He could hardly have foreseen just how big that sacrifice would be.

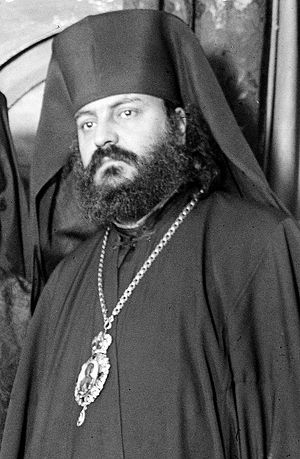

St. Raphael of Brooklyn. Photo: en.wikipedia.org While all this was going on, St. Tikhon, the Russian archbishop, had arranged for St. Raphael to become a bishop himself, giving the Syrians their own hierarch. In early 1904, Nicola traveled from Kearney to New York City, to be present at Raphael’s consecration, and then to be ordained a priest. This was his first big trip away from his kids, and they stayed with family. After his ordination, Fr. Nicola spent time with St. Raphael in Brooklyn and then returned home to Nebraska. But he wasn’t just coming back to pastor the fledgling parish in Kearney—St. Raphael gave him responsibility for an enormous geographic area, covering a territory that’s roughly equivalent to the modern-day Diocese of Wichita and Mid-America. St. Raphael may have been the shepherd to the lost Antiochian sheep of North America, but as a practical matter, that was too much territory for one man to cover in an effective way. So Fr. Nicola would be his deputy, himself a shepherd to the lost Antiochian sheep of the American Plains.

St. Raphael of Brooklyn. Photo: en.wikipedia.org While all this was going on, St. Tikhon, the Russian archbishop, had arranged for St. Raphael to become a bishop himself, giving the Syrians their own hierarch. In early 1904, Nicola traveled from Kearney to New York City, to be present at Raphael’s consecration, and then to be ordained a priest. This was his first big trip away from his kids, and they stayed with family. After his ordination, Fr. Nicola spent time with St. Raphael in Brooklyn and then returned home to Nebraska. But he wasn’t just coming back to pastor the fledgling parish in Kearney—St. Raphael gave him responsibility for an enormous geographic area, covering a territory that’s roughly equivalent to the modern-day Diocese of Wichita and Mid-America. St. Raphael may have been the shepherd to the lost Antiochian sheep of North America, but as a practical matter, that was too much territory for one man to cover in an effective way. So Fr. Nicola would be his deputy, himself a shepherd to the lost Antiochian sheep of the American Plains.

Fr. Nicola’s missionary travels are exhausting to read. If I actually tried to convey an accurate sense of these travels, your eyes would glaze over, and I would never finish this talk. Seriously—this is a big part of Fr. Nicola’s story, but it’s just something I can’t delve into because I’d lose the audience.

So it’ll have to do when I say, he routinely spent six-plus months away from home, leaving behind his four children in the care of his brothers. And we’re talking about trips across vast areas of land, mostly by train and sometimes by horse and buggy, nights spent in all manner of uncomfortable and makeshift beds, cold, heat, loneliness, discomforts of every sort. Again, this would go on for many, many months at a time.

Fr. Nicola didn’t travel so much because wanted to be away from his family. It’s important to understand this, and to understand the difference between Fr. Nicola and St. Raphael. I’ve spent a lot of time studying the life of St. Raphael, and praying to him. He’s a great saint who sacrificed a lot, but he also was restless by nature. He didn’t like to sit still. So his work in America suited him perfectly—he was always on the move, and when he wasn’t on the road away from New York, there were always projects to occupy him there, like building a cathedral and establishing a cemetery. And he was a monk, with no children and nothing to really miss when he was traveling.

Fr. Nicola was very different: from all the evidence we have, he seemed to be more of a homebody, happy to spend months on end working diligently on his little farm (which he had to give up when he became a priest). He was a single parent, with four small children whose mother had died. His correspondence with his children reveals how deeply he loved them. He was not some kind of escapist who wanted to be away from home to avoid family life. He wanted to be with his children, farming the land, and he sacrificed that for the sake of his ministry, to bring the sacraments to Syrian immigrants who otherwise would starve spiritually.

Three years into his priesthood, in April 1907, Fr. Nicola set off on one of his long missionary trips. He expected to be away from his children for many months. But in June, he was in Colorado when he received word that his 11-year-old daughter Anna was very sick, near death. He rushed home, but by the time he arrived in Kearney, she was unconscious. She died on June 7, and Fr. Nicola had to serve her funeral. He wasn’t able to say goodbye, or hear her confession, or give her communion. It is hard to imagine what he must have felt. Surely, an event like this would have broken some men—his service to Christ meant that he wasn’t there for his daughter as she lay dying. But Fr. Nicola did not curse God, or abandon his post.

It would have been completely understandable if Fr. Nicola had cancelled his long missionary journey at this point. His daughter was dead, his sons needed him, and his parish in Kearney needed him, as they too mourned the loss of Anna. How could you blame him for staying home for a long while? But no—Fr. Nicola remained in Kearney for only two or three weeks, and then he was back on the road, back to seeking out those scattered Antiochians and serving liturgies and baptisms and weddings and funerals. Again, he was not an escapist, running away from his grief—he no doubt wanted to be home, but his duty to God came before all else.

In all this, Fr. Nicola’s model was St. Raphael. Over the coming years, Fr. Nicola continued his dual ministry as priest of St. George parish in Kearney and as a traveling missionary throughout the Plains. St. Raphael’s Syrian diocese was growing, and with more priests, there was a hope that Fr. Nicola might have fewer travel obligations. Raphael himself made a return visit to Kearney in September of 1914, and he pushed for the parish to build a new church. Things were looking up.

Met. Germanos Shehedi. Photo: orthodoxwiki.org But on the very day of St. Raphael’s arrival in Kearney that September, storm clouds began to appear over the Syrian diocese: Metropolitan Germanos Shehadi, an Antiochian bishop from Syria, arrived in America. Germanos was ostensibly here for a fundraising trip, to raise money for an agricultural school in his diocese back in Syria. But he also conveniently came to the safety of the United States just as World War I erupted in the Old World. St. Raphael was wary of Germanos’ true motives, but he gave him a blessing to visit the Syrian parishes. For a few months, everything seemed relatively stable.

Met. Germanos Shehedi. Photo: orthodoxwiki.org But on the very day of St. Raphael’s arrival in Kearney that September, storm clouds began to appear over the Syrian diocese: Metropolitan Germanos Shehadi, an Antiochian bishop from Syria, arrived in America. Germanos was ostensibly here for a fundraising trip, to raise money for an agricultural school in his diocese back in Syria. But he also conveniently came to the safety of the United States just as World War I erupted in the Old World. St. Raphael was wary of Germanos’ true motives, but he gave him a blessing to visit the Syrian parishes. For a few months, everything seemed relatively stable.

St. Raphael was only 54 years old, but all his missionary work had put a great strain on his body. He started showing signs of weakness not long after he returned to New York from Kearney, and by the end of 1914, he was bedridden. The end came in February—on February 27, 1915, Fr. Nicola received a telegram in Kearney, informing him that the great bishop was dead. He served a Trisagion for Raphael’s soul on Sunday, and on Tuesday, he boarded a train for Brooklyn, to attend the funeral.

The Syrian diocese pretty much collapsed right then, at the funeral. Syrian priests streamed into Brooklyn in the days following St. Raphael’s death, and as they gathered together, they found themselves in disagreement. Some said that Raphael was under the Russian Church, and so the Russian hierarchy would consecrate a new Syrian bishop. Others disagreed, pointing out that St. Raphael himself had said that his diocese was—and I quote—“a diocese of Antioch, notwithstanding its nominal allegiance to the Russian Holy Synod.” So which would it be—Russia, or Antioch? The Russy-Antacky schism had begun.

Part of the problem was that St. Raphael had no obvious successor. The main pro-Russian candidate was the highly ambitious, highly political Archimandrite Aftimios Ofiesh. His rival-slash-ally was the very young—I’m talking early-to-mid-twenties—Archdeacon Emmanuel Abo-Hatab, who had been St. Raphael’s assistant in his final years. Neither of these men was qualified to be a bishop.1

On the other side, there was that troublesome but charismatic Antiochian metropolitan, Germanos Shehadi. Germanos had taken a shine to America, and America had taken a shine to Germanos. Many, many Syrians thought that of course Germanos should be Raphael’s successor. But there were two problems: one, the Russians weren’t on board with this, and two, the Patriarchate of Antioch didn’t actually want Germanos to stay in America, and over the years, they would keep ordering him to return to Syria.

Archimandrite Aftimios Ofiesh. Photo: ru.wikipedia.org It’s interesting—nobody has ever suggested it, but it seems to me that the best candidate to succeed St. Raphael may actually have been Fr. Nicola himself. He never would have been nominated—he was far to not-political, too humble, too unambitious. He wasn’t part of the circle of influencers in the Syrian diocese—people like Ofiesh and Abo-Hatab and Fr. Basil Kerbawy of the Brooklyn cathedral. But he was canonically eligible, morally upright, and completely self-sacrificing as a pastor. Who knows what would have happened had the Syrians at the time been more open-minded and considered him. He would have been much more worthy than any of the men who were actually in the running, and much more in the mold of St. Raphael himself.

Archimandrite Aftimios Ofiesh. Photo: ru.wikipedia.org It’s interesting—nobody has ever suggested it, but it seems to me that the best candidate to succeed St. Raphael may actually have been Fr. Nicola himself. He never would have been nominated—he was far to not-political, too humble, too unambitious. He wasn’t part of the circle of influencers in the Syrian diocese—people like Ofiesh and Abo-Hatab and Fr. Basil Kerbawy of the Brooklyn cathedral. But he was canonically eligible, morally upright, and completely self-sacrificing as a pastor. Who knows what would have happened had the Syrians at the time been more open-minded and considered him. He would have been much more worthy than any of the men who were actually in the running, and much more in the mold of St. Raphael himself.

But that’s all speculative—no one considered Fr. Nicola as a candidate. Everyone was forced to pick a side—did you want Aftimios, or Germanos? Which was also framed as, should we be under Russia, or under Antioch? In hindsight, there was no right answer. St. Raphael had been highly ambiguous when he talked about Russia and Antioch, and he’d left behind no protégé, no successor. To be blunt, both Aftimios and Germanos were unworthy—anaxios. World War I was raging. The Russian Church waited two years before consecrating Aftimios, and by then Russia itself was in the throes of revolution. In the meantime, Germanos kept picking off parishes and refusing to go back home to Syria.

In the end, Fr. Nicola chose Germanos, which to him would have meant less about Germanos personally (he didn’t really know him that well) and more about choosing Antioch (and not choosing the completely unacceptable Aftimios). I can’t fault Fr. Nicola for that choice. He was totally removed from church politics, trying to make the best decision in an impossible situation, with two really poor options. He suffered for that choice—Emmanuel Abo-Hatab, on behalf of Aftimios and the Russy faction, went around suing all the priests that sided with Germanos, trying to seize their parish property. He filed a lawsuit against Fr. Nicola and won, and in 1918, Emmanuel’s lawyers were in the process of trying to seize Fr. Nicola’s house, when the Spanish flu pandemic hit.

The Spanish flu. In 1918, as troops returned home from the first World War, they brought with them a deadly strain of the flu. It’s estimated that the Spanish flu killed up to 100 million people globally, and in America, about 28% of the population caught it, and over half a million people died. There was widespread panic, and at various times, governments would order quarantines. The flu spread in three waves—the first and least deadly wave came in the spring of 1918. The second began in late summer, peaking in October, when it killed 195,000 Americans in one month.

As all this was happening, Fr. Nicola was busy. He was dealing with the Russy-Antacky lawsuit, and the prospect of losing his house. His son and daughter-in-law were expecting their first baby—his first grandchild. And in September, his new bishop, Metropolitan Germanos, visited Kearney. After Germanos left, Fr. Nicola went on his usual missionary journeys. He probably first heard about this new wave of the flu during his travels, in early October. He visited Wichita, and there was already a citywide quarantine in place, so he couldn’t serve the Divine Liturgy in the new church of St. George—the first Orthodox church in Wichita. While he was in Wichita, he anointed the sick, and he served a funeral for a 16-year-old Syrian girl who died while he was in town. There’s a decent chance that Fr. Nicola caught the flu there, in Wichita.

Then he went back up to Nebraska, visiting scattered groups of Syrians and then returning to Kearney, just in time for the flu outbreak to hit the town. The local and state governments imposed a quarantine. Some of Fr. Nicola’s parishioners were sick, and despite the quarantine, Fr. Nicola took the reserve sacrament and began going house to house, anointing them, giving them communion. A young man in the parish died, and then a toddler. Fr. Nicola served the funerals. More and more people came down with the flu. Fr. Nicola’s own health continued to deteriorate—he was weak, his breathing worsened. He had to have known that he was dying.

But he did not rest. I wonder if it even occurred to him to rest—would it have even been a temptation to a priest who had already so crucified his own will, his own self-interest, for the sake of Christ and his flock? A lesser man—a normal man, really—could have rationalized the need for rest. After all, he had great responsibilities—his parishioners needed him, and all the other Syrians throughout mid-America. His grandchild would be born any day now. His family needed him. But Fr. Nicola did not stop visiting his people, anointing them, giving them communion, helping them either to heal or to prepare for death.

This, in fact, was his own preparation for death. He ministered to his people until he physically could not continue and literally collapsed. This calls to mind the Lord himself, whom Fr. Nicola imitated and served—having loved his own, he loved them to the end (John 13:1). His last words to his sons were, “Keep your hands and your heart clean.” He died at midnight, as October 28 turned to October 29.

The local Kearney newspaper reported, “During the past week Rev. Yanney worked faithfully among his parishioners here, many of them being stricken with the influenza. Considerable exposure to the disease was inevitable and although he had complained of not being the best of health he continued his work uninterrupted until the last.” The Brooklyn Arabic newspaper Al-Nasr wrote of Fr. Nicola’s death, “It was the worst hour when we received the telegram from the children of Father Nicola. They told us that we had lost him because he was always the first to serve the people and the congregation.”

Fr. Nicola lived in the United States in the 20th century. He was not given the opportunity to die a martyr’s death. But we cannot doubt that he would have embraced martyrdom. And the manner of his death echoes the martyric end of another great Antiochian saint, Joseph of Damascus, dean of the patriarchal cathedral where St. Raphael’s parents were parishioners. In 1860, Druze madmen rioted and massacred Orthodox Christians in Damascus. Amidst this chaos and bloodshed, St. Joseph took the reserve sacrament and literally jumped from rooftop to rooftop, going into the homes of his parishioners to prepare them for martyrdom. When he was finally cornered by the Druze, St. Joseph consumed the rest of the sacrament, moments before he was brutally murdered.

Fr. Nicola was not killed by an anti-Christian mob, but his faithfulness, his courage, his patient endurance of suffering, his selflessness, and his devotion to his people to the very end, demonstrate without question that he would have embraced martyrdom, had he been presented with the opportunity.

What, then, is the legacy of Fr. Nicola? He was a pioneering priest, a founder of parishes, a moderately notable historical figure for Antiochian Orthodoxy in America. But to me, his legacy is much more than that: he is an icon of what a priest should be, and a model for all of us—clergy and laity, married and celibate, all Orthodox of whatever jurisdiction—for all of us, he is a model of what true faith looks like in practice. And that legacy belongs, not just to the Antiochians of mid-America, but to all Orthodox Christians, everywhere in the world.

I suppose I should close by saying, may his memory be eternal, but there can be little doubt about that—better, perhaps, to say: Holy Father Nicola, pray to God for us!

Used with permission

Sanctity of Life. A sermon delivered on “Sacred Gift of Life Sunday”''Brothers and sisters, be bold for life. And not because it’s a right but because it’s a gift from God for which all we can do is say thank you.''

Sanctity of Life. A sermon delivered on “Sacred Gift of Life Sunday”''Brothers and sisters, be bold for life. And not because it’s a right but because it’s a gift from God for which all we can do is say thank you.'' St. Raphael’s seminary thesis now available in English: “The True Significance of Sacred Tradition and Its Great Worth”Orthodox Christians of St. Raphael’s time (1860–1915) in the Ottoman Empire were constantly exposed to the proselytization efforts of Catholic and Protestant missionaries. St. Raphael’s thesis is a response to their efforts and claims and represents “an interesting and active dialogue with Western Christianity.”

St. Raphael’s seminary thesis now available in English: “The True Significance of Sacred Tradition and Its Great Worth”Orthodox Christians of St. Raphael’s time (1860–1915) in the Ottoman Empire were constantly exposed to the proselytization efforts of Catholic and Protestant missionaries. St. Raphael’s thesis is a response to their efforts and claims and represents “an interesting and active dialogue with Western Christianity.”