Source: Alaska Dispatch Publishing

Under delicate snowflakes crocheted by the town mayor, beneath a grand chandelier imported from Russia, a Yup’ik priest in a remote Southwest Alaska village led parishioners in song, prayer and praise day and night this week for Orthodox Christmas, or Slaviq.

Most of America took down Christmas trees a week ago, but here in the heart of Orthodox Christian Alaska, people were cutting fresh trees for the holy holiday’s pinnacle on Wednesday, Orthodox Christmas Day. The celebration will stretch on for a week or more.

It’s one of the most significant celebrations of the year for a branch of Christianity tightly braided into Alaska Native culture. This celebration is clearly rooted in church, not the mall. Many Yup’ik people who hold fast to their traditions of living from the land also have latched onto Orthodox Christian traditions, even some that Lower 48 parishes have let go. That includes sticking with the older Julian calendar, which designates Jan. 7 as Christmas Day.

Nowhere in the U.S. is there a higher percentage of Orthodox Christians than Alaska, with 94 parishes, 45 priests and an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 church members, said Bishop David Mahaffey, the Anchorage-based leader of the Orthodox Church in Alaska. For the parts of Alaska that are most deeply Orthodox -- the Aleutian chain and the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Southeast and Kodiak Island -- it's high season.

Schools in a number of deeply Orthodox villages, including Napaskiak, Kwethluk and Kasigluk, all near Bethel, remain closed on winter break, allowing children and families to pray, feast and sing together.

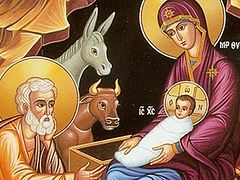

“Kristusaq yuurtuq,” they sang Wednesday in Napaskiak’s St. James Parish church, Yup’ik for “Christ is born.” They caroled house to house in Yup’ik, English and Slavonic, the Eastern European church language, singing songs of rejoicing, of angels and shepherds, of wise men and the star they followed to the manger in Bethlehem, which the Bible describes as the birthplace of Jesus.

Village residents followed shining stars, too, carried from one house to the next by young altar servers who spin them during the singing like super-sized sparkling pinwheels.

“We’re proclaiming that Christ is born in each house, and the star is Christ,” said the Rev. Vasily Fisher, priest of St. James Parish.

'Culture within a culture'

In Western Alaska, the Orthodox religion embraced the Yup’ik culture, and vice versa.

“It’s almost like a culture within a culture,” said Ana Hoffman, a member of St. Sophia Orthodox Church in Bethel and the de facto choir director there.

Many of the priests are Yup’ik and so are the texts.

In Orthodox tradition, greetings bring more than a simple “hello.” Women in close family relationships may kiss on the lips. People pull in during a handshake and press cheeks, first on one side, then twice on the other, Hoffman said.

“Without saying it, you are asking that person to forgive you if you have offended them in any way,” she said. That gets to a Yup’ik way, too, she said. “It’s done through motion and not endless conversation.”

The roots of the village parishes go back to the time of the Russian-American Company and the fur traders, who only went as far north as there were sea otters and seals, Mahaffey said. The Russian missionaries began their work in the late 1700s and early 1800s and their Orthodox religion didn’t spread farther north than the Pribilof Islands on the Bering Sea or past the Yukon River on the mainland, he said.

But the Alaska parishes aren’t Russian Orthodox. They are part of the Orthodox Church in America, which isn’t governed by a mother church in Russia, Mahaffey said.

In fact, it was a Ukrainian bishop who brought with him the traditions of caroling, which is not a Russian custom, and starring, which isn’t done in the Lower 48, said the Rev. Elia Larson, the priest at St. Sophia Orthodox Church.

In Alaska, there weren’t many priests in the church’s early days. The church became the identity of lay leaders along the Kuskokwim River who embraced it, Larson said.

“Our grandfathers, our grandmothers, they became the living continuation of the faith,” he said.

An otter for Christmas

The village of Napaskiak, about 7 miles south of Bethel on the Kuskokwim River ice road, is home to about 400 people, and most of them are both Yup’ik and Orthodox.

Over days of celebration, every home in the village will have opened to carolers and the stars, said Fisher, who originally is from Kwethluk. “Even the Moravian homes are starred,” he said.

In the parish graveyard next to the church, the Williams family this week set up a freshly cut tree and decorated it with twinkly lights. They live just down the boardwalk.

“Their souls in the graves are with us, within us,” said Evan Williams, father of seven, including an adopted grandchild. “We want them to have Christmas too."

The family and the village are between the traditional and modern worlds, he said. His oldest son was checking his cellphone. The Disney Channel was on the big TV.

On Tuesday afternoon, Orthodox Christmas Eve, Evan’s wife Sharon was skinning an otter on the living room floor. She planned to cook it in a soup for a feast for when the carolers and spinning star come to their home, which will probably be Saturday or Sunday. Son Bernard, 16, whom they call “Nardi,” and the village public safety officer trapped the otter out on the tundra, about 50 miles from the village.

Daughter Megan, 17, watched her mother work.

“Mom, can I try?” she asked. It was tricky.

“You are holding your uluq the wrong way,” her mother told her, referring to a curved knife commonly used in several Native cultures. “You have to push down, like this.”

The family celebrated Christmas on Dec. 25 with Santa and gifts for family members.

“This one is for everyone,” Evan Williams said of Orthodox Christmas. “We mainly celebrate this.”

With the otter nearly skinned, the family left for a quick drive on the ice road to Bethel to buy more gifts before church.

A traveling feast

Parishioners came by foot, four-wheeler and truck for Christmas Eve’s Nativity vigil, two services in one that lasted more than two hours, and again for the Divine Liturgy on Christmas Day.

Timothy Jacob, Napaskiak’s mayor, crocheted dozens of snowflakes that hung from the ceiling. The project took him a month, he said. He had been gone from the village for a while and wanted to contribute something.

“My vision was really a magical moment right here, right now, as we approach our Slaviq,” he said.

Joe Bavilla’s grandfather, Fritz Larson, helped build the church. Bavilla wanted to put his mark on it, too. He led an effort to buy the ornate Russian chandelier, which took a crew of a dozen to install.

“It gives light to everybody,” he said.

Men gathered on one side of the worship hall, women on the other. Most stood, as is the tradition. Elders crowded on the few wooden benches.

Fisher, the priest, chanted the names of church saints and the church hierarchy. He walked the borders of the room with sweet-smelling incense. The room got smoky after a while. He sang the story of the Nativity from the Gospel of St. Matthew.

“Nunaniqluni,” he said, a Yup’ik word for a glorious, joyful feeling that could come from inside, or from seeing something wonderful. “The beauty of God.”

The Orthodox service is a scripted interplay between priest, choir and congregation.

As the Christmas service wrapped up, altar servers brought out spinning stars from Napaskiak and the nearby villages of Oscarville and Napakiak, which don't have their own parishes. The youths walked with the stars down the boardwalk. The whole congregation followed. Dozens of people crowded into the small home where the priest, his wife (who goes by her Orthodox name, Olga) and their six children are living temporarily while their parish home is being renovated.

The space grew hot on a day with single-digit temperatures outside. Olga, her mother and other helpers prepared the feast: caribou stir-fry and moose soup, spaghetti with ground beef, jello salad and potato salad, cakes and akutaq, or Eskimo ice cream.

The carolers sang in Yup’ik, English and Slavonic, and then Fisher blessed the food with holy water. The first to eat were the few who had held to the tradition of fasting.

The host traditionally gives gifts to all who come. The priest’s children and others kept passing them out: bars of soap and washcloths, cooking spoons and flashlights, socks and more socks, bags of candy and Cracker Jacks, little toys.

After a few hours, the celebration was set to move on to the home of the assistant priest, then to the home of a priest who died, then to the family who lost a young man in a killing late last year.

It will go on for days. At the end, they will sing in the graveyard, for the souls there.