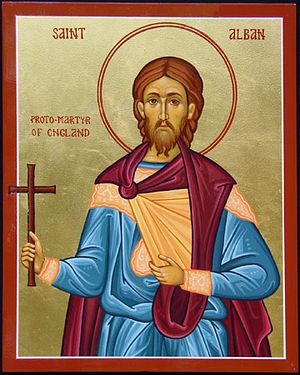

On March 9, 2017, the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church included in the Church calendar the names of fifteen saints who lived in the Western lands before the schism of 1054. Among them are Sts. Alban of Britain and Patrick of Ireland.

The first author to mention St. Alban was St. Venantius Fortunatus of Poitiers (c. 530–c. 605), a bishop, religious poet at the Merovingian court, and hagiographer, in his Praise to Virginity. He calls Alban “fertile Britain’s fruit”. Perhaps this accounts for the early popular veneration of St. Alban in Gaul. He is also mentioned in three early historical documents. However, we find the most detailed and authentic account of St. Alban’s martyrdom in the famous and important work by Venerable Bede of Jarrow, The History of the English Church and People (731), and in the Passions of St. Alban, the First Martyr of Britain (1000), by the learned abbot and hagiographer Aelfric of Eynsham (c. 955–1020). Aelfric mostly relied on the work of Bede. His story is also briefly related by St. Gildas the Wise (c. 500–c. 570), an earlier Church historian and missionary. There are also other and less reliable versions of his Life, written both in Britain and on the continent before and after the Norman Conquest.

The historians still argue as to when exactly St. Alban was martyred. There are three main versions: that it happened about the year 209 under Emperor Septimius Severus (193–211), in 250 under Emperor Decius (249–251), or under Diocletian in about 305. Below is the story of the martyrdom of Alban based on the evidence of St. Bede and Aelfric.

284 years after the incarnation of Christ, a pagan named Diocletian became Roman Emperor. For twenty years he ruled as a ruthless tyrant and ordered Christians everywhere to be killed. The persecutions were at their most savage in 303-305. The brutal persecutions of Christians took place throughout the Roman Empire, reaching even faraway Britain. By that time in other lands many martyrs had already given their lives for Christ. The first martyr who laid down his life for Christ in Britain was the glorious Martyr Alban.

By the year 305, the bloody persecutions of the impious Diocletian had reached Britain and the murderers with frenzied brutality seized Christians throughout the island. One priest managed to flee from the persecutors. In his flight he saw a house where a man called Alban lived. He knocked on the door, seeking shelter from the merciless pursuers. Though Alban had not yet been enlightened by Holy Baptism, he let the priest in and gave him refuge. Of the life of Alban before his martyrdom we only know that he was most probably a soldier and most likely a Romano-Briton, though some researchers argue that he was a Roman (his name is derived from the Latin word “albus” which means “white”).

The priest daily read all the services, sang Church hymns, prayed day and night and kept a strict fast. He regularly instructed Alban in the true faith and told him about God until the saint, enlightened by the grace of the Holy Spirit, rejected the darkness of paganism and came to believe in Christ, was baptized by him and became a faithful Christian.

But the priest was not to live at St. Alban’s house for long. Soon the unrighteous ruler of that region heard that a Christian priest had found refuge in his house. Furious, he ordered his men to go and bring him the cleric and execute him. As soon as the envoys had approached his house, Alban exchanged clothes with the priest in order not to betray him and went out to meet them as if he were the priest. Alban was immediately tied up and led to the vicious magistrate who at that very moment was offering sacrifices to his “gods”—that is, demons.

Seeing the brave martyr, the magistrate flew into a rage, as he understood that their fellow-countryman had hidden a fugitive priest in his own house and, apart from this, had also resolved to die instead of him. He ordered that Alban be taken to the idols, and when this was done he warned the saint that he would be severely punished in the priest’s place if he did not renounce his new faith and bow down before the heathen idols immediately. However, the noble martyr, strengthened by the divine grace for spiritual battle, did not fear these threats at all. He replied that he would neither carry out the judge’s orders nor venerate the lifeless images.

The judge asked him: “What family are you from and what is your social status?” Alban answered: “It’s none of your business what family I come from! If you want to know the truth, I will tell you that I am a Christian and I will serve Christ alone—the only true God.” “Tell me your name at last!” the magistrate demanded. The fearless soldier of Christ said: “My name is Alban, and I believe in Christ the Savior—the true God Who created the world and all things. It is He Whom I confess and Whom I will worship and pray to forever!” The judge responded: “If you want to enjoy the bliss of eternal life, then make a sacrifice to our great gods right away!” Alban then answered: “Your sacrifices are offered not to gods, but to demons, and they will never help you. But you should know that as eternal punishment for idol-worship you will be cast into hellfire forever.”

Enraged, the judge demanded that the saint be flogged, thinking that physical suffering would weaken him, making him lose heart and turn to paganism. But the martyr, strengthened by the Lord, bore the blows with patience, as if it were happening not to him, and thanked God for being vouchsafed suffering for Him. The judge realized that he would not be able to force Alban to renounce Christ and ordered him to be executed.

The pagans led the saint to the site of execution in order to behead him. But as they were crossing a bridge over the River Ver, they had to stop because a great multitude of people—men and women—came to look at the glorious martyr and thus crowded the bridge. Meanwhile the bloodthirsty and ungodly magistrate remained in the city till the evening with neither servants nor assistants near him, fasting against his own will.

Wishing to die for Christ sooner, the brave martyr Alban came down to the river (as he was unable to cross the bridge) and began to pray, looking above to heaven. According to tradition, suddenly the waters of the river parted, exposing the bed, and a path to the opposite bank appeared—it was precisely what he had asked for in prayer. The executioner who was to execute Alban was so struck by the miracle that he at once threw his sword down. He ran after Alban, and as soon as they had both crossed the river, he fell before his feet and admitted that now he wanted to die with him and not to behead him. Now the holy faith united them—the former executioner and the martyr whom he had been ordered to execute.

There was a gently sloping hill nearby with many-colored wonderful flowers growing on it. It looked as if it had long prepared its beauty to receive the holy blood of the great martyr. It is traditionally believed that it was Holmhurst Hill, later renamed to Holywell Hill, where St. Alban’s blood was shed, and it exists to this day. Alban rapidly ascended it and in prayer asked God to send water to the hill. At once a spring gushed forth at the saint’s very feet and swiftly ran downhill, and so the gathered people understood that a miracle had been performed by God through Alban’s prayers and that even nature obeyed holy men. The spring existed for many centuries and had healing properties, which was evidenced by Venerable Bede and many others.

St. Alban was beheaded on the hill and was granted a martyr’s crown in Paradise. But the man who executed him never saw Alban’s dead body—his eyes fell out of their sockets to the ground at the same moment. Ever since, artists have often depicted this scene. Then the executioner who had refused to kill the martyr was put to death as well. His name remains unknown. His body fell beside St. Alban’s holy body. The repentant executioner died on coming to believe in the true God, thus being baptized by his own blood—and his soul was taken to heaven. In the first centuries of Christianity there were many other martyrs who died for Christ in this way. According to Bede, when the executioners returned to the city they recounted to the ruler the numerous miracles performed through the intercession of St. Alban. Soon after that, he stopped the persecutions and thenceforth spoke with respect of the martyrs whom he had previously put to death himself and had proven unable to convert to paganism by means of brutal tortures.

The Roman amphitheater at Caerleon in Newport, Wales, where Sts. Julius and Aaron were presumably martyred

The Roman amphitheater at Caerleon in Newport, Wales, where Sts. Julius and Aaron were presumably martyred According to Aelfric and other early authors, during the same period of persecutions a multitude of other martyrs of both sexes died for Christ in all regions of Britain, having borne many tortures and much suffering. Among them were the saints who have been known as the Protomartyrs of Wales. They are Sts. Julius, Aaron (a Jewish name) and their companions, who were presumably martyred at Caerleon-on-Usk in about 305 and much venerated after that (feast: July 1/14). And here we should make a very important conclusion. The early Christian theologian Tertullian (c. 160–c. 240?) in his work Apologeticus said that the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church. As elsewhere in the world, these words proved true in Britain. For the holy blood of Sts. Alban, Julius, Aaron and a host of other unknown early Orthodox martyrs indeed was the seed of the Church in the British Isles, which prospered in the Orthodox tradition for several centuries afterwards, largely due to the feat of these martyrs. The growth and development of Orthodoxy in these lands became possible after that. And as Bede and other historians further relate, when the persecutions stopped, Christians came out of the woods and other hiding-places. They began to live among people and gradually revived Christianity—they restored the ruined and destroyed churches and lived in peace with all in the true faith. On the site of Alban’s martyrdom a splendid church worthy of the glorious saint was built as well. The Venerable Bede witnessed that in his time healings and many other miracles occurred at that church unceasingly.

Alban was martyred just outside the Roman city of Verulamium, which was the third largest Roman settlement in Britain. Thus, Alban was a local. Verulamium bore this name until about 948, when it was renamed St. Albans—after the saint. It is called St. Albans to this day. This town is just nineteen miles (about thirty-one kilometers) north of London, in the western part of county Hertfordshire in eastern England. Not long ago, archeologists found remains of a Roman cemetery and presumably an early church on a hill near the present Cathedral.

So Alban was buried near Verulamium (later St. Albans) and apart from the large church above his grave from the earliest times there was also a monastery in the town. The time of the foundation of the first monastery is sadly unknown. But it is certain that King Offa of Mercia (ruled 757-796) revived or rebuilt the monastery there. By the Middle Ages the monastery in honor of St. Alban was among the greatest and wealthiest in the country.

Let us mention several interesting facts concerning the early veneration of Alban. This is virtually the only saint who is a connecting link between fourth-century England and the early patristic period in mainland Europe, as well as the period of the late Roman Empire. Notably, the two outstanding Church figures: Sts. Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes (whose names were also included in the Church calendar of the Russian Orthodox Church in March 2017) visited Verulamium in 429. They took a small portion of the saint’s relics to Gaul (this fact accounts for his early widespread veneration on the continent) and gave the church numerous particles of the relics of apostles and martyrs. That is why the first recorded Church veneration of St. Alban is in 429. A large number of early churches in France are dedicated to a “St. Alban”, though it is impossible to identify whether the saint in question is St. Alban of Verulamium or St. Alban of Mainz—another deeply venerated saint (by legend, a Greek priest who preached Christ around Mainz in Germany and was eventually killed by Arians in c. 400; feast: June 21). Ely Monastery in Cambridgeshire claimed that it received a portion of St. Alban’s relics in the eleventh century under Abbot Frederick. This version has always been questioned, however Ely still has a feast-day commemorating this event—the translation of St. Alban’s relics (May 15), though St. Albans denied the authenticity of this translation.

After the Norman Conquest, the popularity of the Abbey and the silver-gilt shrine encrusted with jewels, containing the saint’s relics, remained the same. The Normans built a new and huge Catholic monastery in honor of Alban in St. Albans—the construction work began in 1077 and the edifice was consecrated in 1115. This monastery became one of the most visited in all Britain. A controversial event occurred in the twelfth century. It was Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100–1155)—a historian notorious for inventing a great many tales and myths1 that he portrayed as “the history of Britain”—who wrote of “St. Amphibalus”. Amphibalus was allegedly the priest whom Alban gave shelter in his house. Although he was supported by no early sources, Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that this Amphibalus later preached Christ in Wales and England and was finally murdered by pagans. Eventually, in 1177, somebody’s remains were discovered at Redbourn near St. Albans and was declared “St. Amphibalus’ holy relics” and enshrined at St. Albans. However, the word “amphibalus” (or the similar form: amphibalo) is not a name, but a word meaning a priest’s cloak I which St. Alban dressed himself, in order to save the priest from persecutors. There had obviously been a mistake. The twelfth-century story of Amphibalus is rejected by scholars as a medieval forgery.

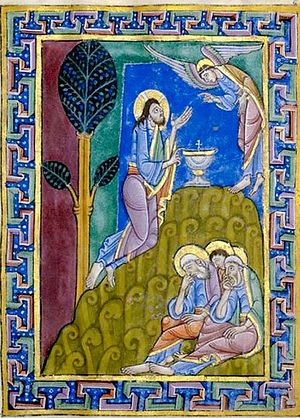

St. Alban's Psalter. A detail depicting the Agony of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane (photo from Wikipedia)

St. Alban's Psalter. A detail depicting the Agony of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane (photo from Wikipedia) The importance and prestige of the Abbey grew in spite of the catastrophic “Black Death” plague in the fourteenth century. It had as many as twenty dependent monastic communities elsewhere. Its abbots were held in high esteem. At its height, the monastery had over 100 monks at a time. Interestingly, the first draft of the famous “Magna Carta” of 1215 was laid down at St. Alban’s. Roughly from the time of King Offa till the nineteenth century, there was “the Liberty of St. Alban” which comprised what is now Hertfordshire. The abbey was so great that Edward I granted St. Albans Abbot palatine status (royal prerogatives within a given area), which was also enjoyed by the bishops of Durham and Ely. Only after the sixteenth-century Reformation was the monastery closed (1539), the shrine smashed to pieces, and the former abbey church purchased by the townspeople in 1553 and used as a parish church for 300 years. By the nineteenth century, the church’s condition had deteriorated so much that only the choir and the presbytery were fit for worship. Large-scale restoration work followed, and the church has been used as an Anglican cathedral since 1877. The cathedral is dedicated to St. Alban and is often called “St. Alban’s Abbey”. Soon after the Reformation, St. Alban’s relics were moved to Germany.

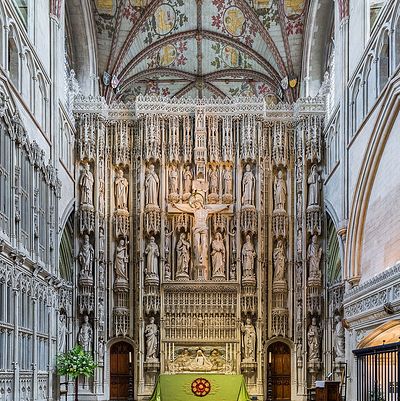

The very beautiful and splendid thirteenth-century shrine, whose 2,000 fragments were unexpectedly discovered in 1872, was “reassembled” and most carefully restored by 1993, and by the mercy of God, in 2002, a portion of St. Alban’s relics (a shoulder bone) was returned to the town from the tenth-century Romanesque St. Panteleimon’s Church in Cologne (Germany), where it had been kept for 1000 years, and solemnly enshrined. Today St. Albans Cathedral is a popular pilgrimage destination. The patron saint, Alban, is now venerated by Orthodox, Catholics, Anglicans and Lutherans. St. Alban’s chapel, also called “the heart of the cathedral”, is situated beyond the high altar and contains the restored Purbeck marble shrine and an Orthodox icon of St. Alban. Remarkably, it holds regular Russian Orthodox services. The cathedral’s congregation celebrates St. Alban’s memory on June 22 (his feast according to the new calendar) with prayers and processions to his shrine, with participants holding roses in their hands. The city of St. Albans also has a Museum of Verulamium with some ruins and numerous artifacts, Verulamium Park and a partly surviving holy well of St. Alban.

This is what Derry Brabbs, a well-known contemporary traveler and author of books on Britain’s ancient monuments, writes of St. Albans Cathedral in his book, Abbeys and Monasteries in Great Britain (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1999, reprinted 2003 for Eagle Editions LTD; p. 35):

“St. Alban was England’s first Christian martyr, executed for his beliefs by the Romans early in the fourth century. None of the buildings from earlier monasteries established on Alban's tomb has survived, and the mighty abbey church around which the city of St. Albans grew was started by the first Norman abbot, Paul of Caen. As there were no local sources of stone, the builders utilized brick from the adjacent ruined Roman city of Verulamium. St. Albans took highest rank among medieval abbeys, favored by a decree from Pope Adrian IV in 1154 declaring that its abbot should be the senior mitred abbot in Parliament. It may be coincidental, but that particular pontiff was the only pope to come from England, Nicholas Breakspear, born not far from St. Albans. A case of nepotism, perhaps? The church has a long nave of twelve bays, some pillars of which are decorated with recently restored medieval wall paintings, helping to alleviate Norman austerity. Medieval designs have been repainted on to the wooden chancel ceiling, providing а perfect visual foil for the exquisite stone screen beneath. Nineteenth-century restoration, although vital in preserving much of the abbey’s fabric, was less than sympathetic to the abbey’s origins. Although work was generously financed by Lord Grimthorpe, a Victorian architect and lawyer, unfortunately he insisted on his own restoration plans.”

Let us add more facts about St. Alban’s Cathedral, perhaps one of the most visited holy places in England, which is nearly 1000 years old. When the Normans built it, this church was the largest in England. Apart from the former abbey gatehouse, it is all that remains of the great Benedictine monastery. The church itself is said to be the second longest in Britain (550 feet or 168 meters long). It has the longest nave in the whole country—its length is 275 feet (eighty-four meters). Its newest part is the west front, which was rebuilt during the nineteenth-century reconstruction. Its austere, solid and amazingly proportioned tower (seven feet or 2.1 meters thick and 144 feet or 44 meters long), the oldest cathedral tower in the country, has Roman bricks in its fabric—in fact, brick from the Roman city of Verulamium was actively used in building the previous Saxon and the present churches. Its interior has features of the Romanesque, Early English and Decorated Gothic styles. The Lady Chapel, which had been completed by 1320, was walled off from the rest of the church following the Reformation and used as a school for 300 years. It was reattached to the cathedral only in the nineteenth century. The modern addition to the cathedral is the chapter house, which was built in the pseudo-Romanesque, style and opened in 1982 with the participation of Her Majesty the Queen. A stone screen separates the nave from the presbytery and the choir. There is a wooden balcony over St. Alban’s shrine—it was from this loft that a monk watched over the church’s precious relics every day before the destructive Reformation. On the south side of St. Alban’s shrine lies the only royal tomb within the cathedral: that of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390-1447), who was a brother of King Henry V and benefactor of the abbey.

The formerly whitewashed and subsequently rediscovered exquisite thirteenth-fourteenth century wall paintings and murals depict crucifixions, many scenes and aspects of the Savior’s life and Passion, scenes from the life of the Mother of God, with shields of many early English saints. Among the best-known paintings are those of Christ in majesty and the incredulity of Apostle Thomas. The sixty-six panels of painted ceiling of the choir and the presbytery’s painted ceiling are superb. The north choir aisle contains a replica of the unique fourteenth-century astronomical clock, created by Abbot Richard Wallingford. After the Reformation, the statues of saints by the fine fourteenth-century screen of the high altar were beheaded or smashed, and it was only in the 1890s that it was decided to carve and install new statues of apostles and early English saints in their place. A prominent feature of the cathedral is the twelfth-century marble altar table in the north transept—a survival from the old abbey; the altar is now uniquely dedicated to the persecuted Church, uniting St. Alban with all other martyrs throughout the history up to our times.

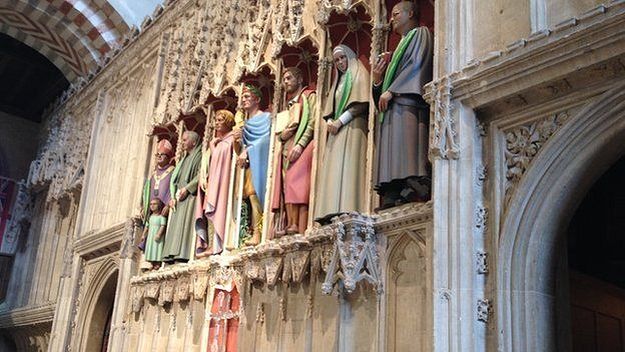

The seven new statues at St. Albans Cathedral - St. Alban is fourth from the left, St. Elisabeth is sixth from the left (source - BBC.com)

The seven new statues at St. Albans Cathedral - St. Alban is fourth from the left, St. Elisabeth is sixth from the left (source - BBC.com) The grand “Michael Stair” was installed in the 1980s to provide the majestic entrance into the main cathedral from the chapter house. Some fabric in the transepts is uniquely of the Saxon and the Roman origin. In fact, the main transept walls have stood practically intact from Norman times, which makes them the cathedral’s oldest surviving feature apart from the tower. The oldest stained glass at the cathedral can be found in the north transept, and stained glass images of the nineteenth and twentieth century are installed in the south transept, the Lady Chapel and near St. Alban’s Chapel. In 2015, seven new painted statues of martyrs of various Christian denominations and different epochs were installed at the cathedral, and among them is a statue of the New Martyr Elizabeth Fedorovna Romanova.

The Roman Catholic Monastery of St. Michael in Farnborough in the county of Hampshire also has a relic of the Protomartyr of Britain. There is an Orthodox small community of St. Alban in St. Albans, belonging to the Exarchate of Orthodox Parishes of the Russian Tradition in Western Europe; there also a parish of St. Alban in the Sourozh Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church in Luton, Bedfordshire and a Romanian Orthodox community of Sts. John the Baptist and Alban in the same town.

St. Alban has been venerated all over England (where nine ancient churches were dedicated to him) and in many other countries since the earliest times. A portion of his relics was kept at Odense in Denmark from the early Middle Ages; the town had a priory of St. Alban that was later transformed into St. Canute’s Cathedral. Now Odense has a cathedral and a Catholic church of the Mother of God, St. Alban and St. Canute where our martyr is venerated. Dozens of churches, several cathedrals and monasteries are dedicated to him in England, Denmark (for example, the “English” St. Alban’s Church in Copenhagen), Germany, France, Switzerland, Italy, Canada, the USA, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and even Japan. The annual largest city festival in Switzerland, Albanifest, held in the city of Winterthur in the canton of Zürich at the last weekend of June, is named after St. Alban because some 750 years ago this city was granted the charter precisely on his feast day.

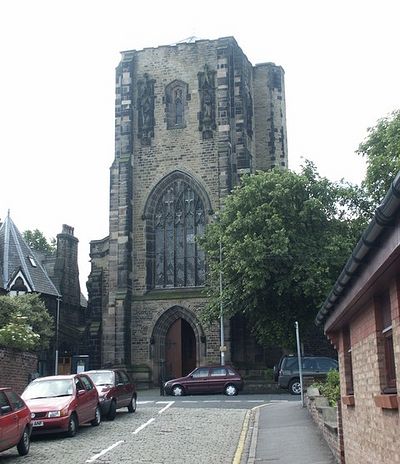

St. Alban's Church in Wallasey, Merseyside

St. Alban's Church in Wallasey, Merseyside Among England’s churches which bear the name of St. Alban let us mention the following ones: St. Alban’s Church in Holborn, London; a church in Croydon in the south of London; the church in Wickersley in South Yorkshire; a church in the resort town of Bournemouth in Dorset; the church in Forest Town in Nottinghamshire; the church in Gossops Green, now within the town of Crawley in West Sussex; St. Alban’s Catholic Church in Macclesfield in Cheshire; the Catholic church in the town of Warrington in Cheshire; the Catholic church in Liscard area within the town of Wallasey in Merseyside; one of the numerous Anglican parish churches in Birmingham; Anglican churches in Withernwick in East Riding of Yorkshire; Dartford in Kent; the Swaythling district of Southampton, Hampshire; in the village of Tattenhall in Cheshire; in Westbury Park in Bristol; in the village with the interesting name of Windy Nook in Tyne and Wear; in Trimdon Grange in County Durham; in Lakenham near the city of Norwich in Norfolk; in the village of Earsdon in Tyne and Wear (the earlier name is Erdesdun, meaning “hill of red earth”, and the church was originally under the care of Tynemouth monastic community which, in its turn, was ruled by St. Albans Monastery) and many others.

St. Alban's Church in Trimdon Grange, Durham

St. Alban's Church in Trimdon Grange, Durham

A town in the state of New South Wales in Australia is called St. Albans. A number of colleges and schools in several English-speaking countries are named after our saint. “St. Alban’s Cross” is a yellow saltire (St. Andrew’s cross) on a blue background. It is a part of the flags of the current St. Albans Cathedral and the town of St. Albans in Hertfordshire.

***

From time immemorial, England was called Albion because of her white cliffs, which can be seen from the coast of France. And the name of her first martyr, Alban, also means “white”. We firmly believe that the very name of St. Alban predetermined that he became one of the symbols and chief patrons of this country. Let us hope and pray that through his intercession the ancient faith and spirituality will be restored in this ancient Orthodox Christian land.

Holy Martyr Alban of Verulamium, pray to God for us!