Throughout the centuries, on the eve of the Transfiguration many monks leave the Great Lavra with pack animals loaded with provisions, vestments, and church vessels, and climb to the top of Mt. Athos, 2033 meters above sea level, higher than the clouds, where there is a tiny chapel of the Transfiguration of the Lord. On the evening of the following day they will serve the Vigil according to the typicon of other monasteries on the Holy Mountain. Gradually climbing the mountain, like once the apostles did “on a high mountain” (Matt. 17:1), they sing the hymns for the forefeast to the rhythm of the tinkling bells on the mules: “Let us come together with Jesus, and climb the holy mountain.”

Pilgrims of various nationalities, from other parts of Mt. Athos, join them along the road. The forming procession reminds one of the Jews who gathered from all corners of Palestine together with the “strangers that came out of that land” to celebrate in the house of the Lord on Sion (2 Chron. 30:25), For thither did the tribes go up, the tribes of the Lord, the testimony of Israel, to give thanks unto the name of the Lord (Ps. 121:4).

This “holy peak”, often covered with pure, white snow, at times reflecting the sun’s rays, at times shrouded in clouds, was destined to become the “Mountain of Light”; after all, the ancient world “aithon” means “fiery, radiant, gleaming”. This peak occupies a special place in the heart of the hagiorites. They see in it the axis of the earth that unites heaven with the earth; a kind of pillar along which prayer rises to God—a footstool of God’s throne, the chosen dwelling-place of the All-reigning Queen, the “Mother of the Light”.

Numberless icons and frescoes depict the Theotokos in the Heavens upon the snowy peak of Mt. Athos, covering the world with her Omophorion, the “holy protecting veil” of her prayer.

According to the unshakeable ancient tradition, monks ascend here from time to time to pray closer to heaven and receive from God answers to important questions in their lives.

It was here in the tenth century, on the day of the Transfiguration, that the churchwarden of the Iveron Monastery St. Euthemios beheld the divine light, glimmering like a burning fire, in the hour that he served the Liturgy. “Suddenly, an extremely bright light shone all around, and the earth trembled. All fell to the ground, and only blessed Euphemios remained standing like a pillar of fire, immoveable before the holy table of oblation.”

Four centuries later, the Theotokos appeared to St. Maxim the Kapsokalivite, surrounded by a bright light and fragrance, holding the Lord in her hands, Who blessed St. Maxim and filled him with holy exaltation. Another century later on the same place, where this miracle happened, which was kept secret, Elder Joseph (+1959), the great hesychast and true father of modern-day revival of the tradition of mental prayer on the Holy Mountain, met his co-ascetic Elder Arseny (+1983) and began living a severe ascetic life, wandering across the slopes of the Holy Mountain. Then one day, when he was overcome by despondency, from this same peak a shining ray of light shone and entered into his heart. From that time on, just as on Mt. Tabor, his mind and heart abode always in Jesus.

There is a tradition that seven ascetics live on this peak, naked and known to no one, preserving through the ages and passing on from generation to generation the mystical tradition of asceticism and contemplation.

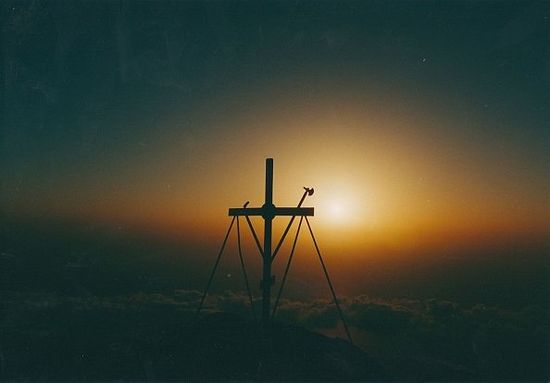

Whether or not this tradition is true, it shows how important the “Holy Peak” is in the consciousness and life of the hagiorites. Therefore the tiny chapel of the Transfiguration and the tall metal cross standing next to it on that narrow cliff have a special symbolism, and portray to heaven and earth the two characteristic components of monastic life: experience of the Cross, the voluntary and constant participation in the Lord’s Passion, which is at the same time also the path of theosis, and life in the light of eschatological glory that Christ once revealed to the apostles on Mt. Tabor. As the Lord ascended the mountain with His chosen the disciples in order to pray (Lk. 9:28), so also do monks, who have renounced the world, live on Mt. Athos in quietude and prayer, living here and now in the light of the Transfiguration. Athos for them is Tabor, a prefiguration of the Kingdom of Heaven.

At the sunset of the Byzantine Empire, when St. Gregory Palamas, a monk of the Holy Mountain and a great theoretician of divine light, was struggling against the humanists and defending hesychasts, supporting the Orthodox teaching on man’s theosis (deification)—his real participation in the life of God through uncreated grace—the theme of the Transfiguration and the nature of the light of Tabor were the center of attention. In all of his writings, St. Gregory Palamas and his supporters make numerous references to this holy event and show that the Transfiguration of the Lord, as the example of our personal deification, is primarily a monastic feast, a feast of the Holy Mountain. Many long years did St. Gregory live at the base of Mt. Athos in the Great Lavra, in the cell of St. Savva, located high in the mountains. Therefore, for every modern hagiorite, Mt. Athos is equated with Tabor and with every “mountain of the Lord” where the Lord was revealed to men. For them, this is Mt. Sion, Mt. Carmel, the Mount of Olives, and Golgotha. Moreover Mt. Athos is for them also like other “holy mountains”, where the Lord made His abode “in His holy place” (Ps. 150:1) “in the midst of the Gods (Ps. 81:1). This in part is Olympus in Bithynia, from whence came the first hagiorites, Mt. Latmos, Mt. Ganos, the mountain of St. Auxentius and other glorious monastic centers in Asia Minor, and the holy mountains of Greece. We can also draw a parallel with Mt. Olympus—the ancient abode of twelve gods. Mt. Athos is related also to the holy cliffs of Meteora, on the highest of which is the Monastery of the Transfiguration, the mountains of the Peloponnese, Macedonia, the Carpathian mountains, Serbia, Armenia with its great Ararat, the Caucasus mountains and the mountains of Russia, as well as the “little mountain” of St. Seraphim in the Sarov forest, Monte Cassino of St. Benedict, Mt. Mercurius—the citadel of the Byzantine ascetics of Calabria—and all the other holy mountains of the Orthodox West. Thus, Mt. Athos can be equated with all mountains like Tabor, for monks of all times, living here.

On this night in the tiny chapel, where only a few people can stand at a time, while all the others try to warm themselves by the big campfire burning outside, the voices of the chanters are transformed into an ecclesiastical trumpet, proclaiming to the world news of the Eternal Light.