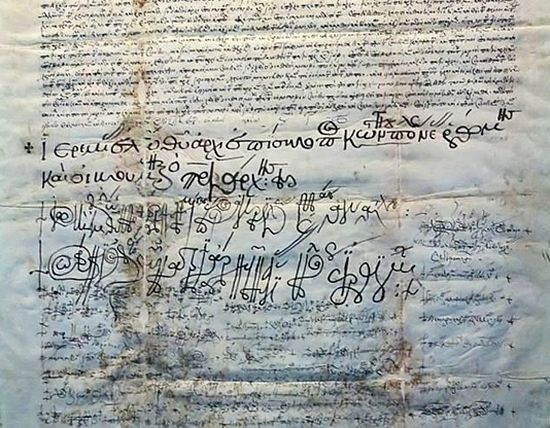

17. Establishment of the Moscow Patriarchate

Gramota of the Synod of Constantinople on the founding of the Moscow Patriarchate, May 8, 1590

Gramota of the Synod of Constantinople on the founding of the Moscow Patriarchate, May 8, 1590

After a period of de facto autocephaly, the Russian Orthodox Church had received its charter from the Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1588, granting it its own Patriarch. After Malorussia and Belorussia had become part of the Russian Empire, the Russian Orthodox Church hoped that, with the reuniting of these ancient Russian lands, the divided Church would also be reunited. But this did not turn out to be so simple—through the centuries of unrelenting pressure, the Uniate Church had already been sufficiently established in Galicia.

18. Submission of the Kiev Metropolitanate to the Moscow Patriarch

The Little Russians were divided on the subject of joining the Moscow Patriarchate. The masses and lower ranking Cossacks looked toward Moscow, but the Cossack leaders and aristocracy preferred the autonomy they enjoyed from a far-away Patriarch of Constantinople to the real and near authority of Moscow. Under the important leadership of the scholarly Metropolitan Peter Mogila, the Orthodox Church in Kiev had begun to grow into its own after long neglect. Politically, Little Russia was divided into two parts—the Cossack leaders wanted to retain the free-wheeling status they enjoyed, and hoped even to raise themselves to the dignity of the Polish landowners, while the lower classes were thoroughly weary of the latter’s tyranny, and felt relief under Russian rule. Little Russia entered a prolonged time of difficulties, rife with betrayals and internecine wars— Cossack leaders appealing now to Moscow, now to Warsaw

During this period, the late seventeenth century, political leanings directly affected the Kiev hierarchs’ inclinations. Just as the King of Poland had always appointed the Kiev Metropolitan, so the Cossack leader Bogdan Khmelnitsky and his successors were now placing their own candidates on the Metropolitan’s throne. There were also presiding hierarchs appointed by Moscow who then defected to Poland, and vice versa. Anathemas were exchanged, and the people were left to guess as to who was right and who was wrong. Finally, a peace treaty was signed between Poland and Russia in 1686; and although the Kiev Metropolitan was not entirely willing to be consecrated by the Moscow Patriarch, the unification was ratified in Constantinople in 1687, putting an end to the two-hundred-year-long separation. Some historians say that Moscow influenced the Ottomans to pressure the Constantinople Patriarch into ceding Kiev to Moscow. In any case, one historical result is the important contribution to Russian Orthodoxy of Little Russian saints, such as that of St. Job of Pochaev, St. Dimitry of Rostov, St. Paisius Velichkovsky, and others.

However, the Orthodox dioceses remaining in the torn-away Lithuanian regions and Galicia had no option to unite with Moscow, whether they wanted to or not—and now, deprived of support even from Little Russia, they were completely downtrodden.

Russian historian A. P. Dobroklonsky wrote of difficulties endured by Belorussian and Galician Orthodox in the period prior to the return of Volhynia and Little Russia to Russian protection in 1795:

The Orthodox suffered every possible restriction. In 1717 the Sejm deprived them of their right to elect deputies to the [local] sejms, and forbade the construction of new and the repairing of old churches; in 1733 the Sejm removed them from all public posts. If that is how the government itself treated them, their enemies could boldly fall upon them with fanatical spite. The Orthodox were deprived of all their dioceses and with great difficulty held on to one, the Belorussian; they were also deprived of the brotherhoods, which either disappeared or accepted the Unia. Monasteries and parish churches with their lands were forcibly taken from them…. From 1721 to 1747, according to the calculations of the Belorussian Bishop Jerome, 165 Orthodox churches were removed, so that by 1755 in the whole of the Belorussian diocese there remained only 130; and these were in a pitiful state.… Orthodox religious processions were broken up, and Orthodox holy things subjected to mockery…. The Dominicans and Basilians acted in the same way, being sent as missionaries to Belorussia and the Ukraine—those “lands of the infidels,” as the Catholics called them—to convert the Orthodox…. They went round the villages and recruited people to the Unia; any of those recruited who carried out Orthodox needs was punished as an apostate. Orthodox monasteries were often subjected to attacks by peasants and schoolboys; the monks suffered beatings, mutilations, and death. “How many of them,” exclaimed [Archbishop] George Konissky,36 “were thrown out of their homes! Many of them were put in prisons, in deep pits; they were shut up in kennels with the dogs, they were starved by hunger and thirst, fed on hay; how many were beaten and mutilated, and some even killed!”… The Orthodox white clergy were reduced to poverty, ignorance, and extreme humiliation. All the Belorussian bishops were subjected to insults, and some even to armed assault….37

It was also during this time, in 1720, that the Pochaev Monastery was seized by the Catholics, and Uniate monks replaced the Orthodox—an occupation that would last 110 years.

The confusing movement back and forth between Moscow and Warsaw continued until the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth weakened and broke apart.

19. Crimea and Novorossia Become Part of Russia

During the late eighteenth century, following the Russian-Turkish War, Russia annexed the territory of the Crimean Khanate, an arm of the Ottoman Empire, which included the Crimean peninsula and eastern steppes on the mainland—an area called then Novorossia—“New Russia.” Following this, Empress Catherine II expanded Russian territory into this area, populated by a Turkic people who had mingled over the centuries with the Mongol hordes. They had made the Crimea a slave-trading station—the slaves being southern Russians, who were in high demand by the Ottomans. St. John the Russian38 (also most likely from that area) was one of these victims of human trafficking, who nevertheless achieved great sanctity in Turkish captivity. Western Europe took a dim view of Catherine’s expansion, but the resulting cessation of raids on the people to sell them into slavery was no doubt a welcome change to the local population.

(This territory would become part of the Ukraine only after the 1917 revolution, when Lenin annexed the mainland territory to the Ukraine in order to entice Ukrainians into the USSR. The Crimean peninsula was annexed to the Ukrainian Socialist Republic later by Nikita Krushchev, also of Ukrainian descent, as another pro-Ukrainian gesture.)

20. Return to Orthodoxy

It was also during the reign of Catherine II that Poland was partitioned. Three successive partitions, from 1772 to 1795, saw the oncepowerful Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth divided between Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Volhynia and Belorussia (as also Poland) became part of the Russian Empire. The higher clergy of the Uniate Church were typically pro-Polish. Russian rule favored either a return of the Uniates to Orthodoxy, or a conversion to Latin Catholicism. Now under a new, Orthodox monarch, many Uniates were in fact happy to return to Orthodoxy, and did so. A leading figure in this reversion was the Uniate Bishop Joseph Semashko.39

Metropolitan Joseph Semashko. The Polish uprising against Russian rule, which took place in November 1831, was officially supported by the Uniate Church. After this revolt failed, the Russian authorities began their strategy of removing all Uniate synod members and stripping the Polish magnates of their privileges. As Polish influence waned in Volhynia, so did the Unia. In 1831, the Pochaev Lavra was returned to the Russian Orthodox Church (with which it staunchly remains to this day), and in 1839 the now Orthodox Bishop Joseph Semashko led the Synod of Polotsk (Belorussia), and the Union of Brest was terminated. (There are no Uniate churches in Belorussia today, while Roman Catholic churches function there in larger numbers than in Russia.) All Uniate churches in the Russian Empire—which included Belorussia and the Right Bank Ukraine40—were incorporated into the Russian Orthodox Church. Those members of the clergy who did not desire to become Orthodox—amounting to about a quarter of the total—were deprived of their clerical status. Unfortunately, many were even persecuted. The territories that had become part of the Russian Empire later than others naturally had more Uniates. After the decree of religious tolerance issued in 1905, they would be allowed to remain Uniates.

Metropolitan Joseph Semashko. The Polish uprising against Russian rule, which took place in November 1831, was officially supported by the Uniate Church. After this revolt failed, the Russian authorities began their strategy of removing all Uniate synod members and stripping the Polish magnates of their privileges. As Polish influence waned in Volhynia, so did the Unia. In 1831, the Pochaev Lavra was returned to the Russian Orthodox Church (with which it staunchly remains to this day), and in 1839 the now Orthodox Bishop Joseph Semashko led the Synod of Polotsk (Belorussia), and the Union of Brest was terminated. (There are no Uniate churches in Belorussia today, while Roman Catholic churches function there in larger numbers than in Russia.) All Uniate churches in the Russian Empire—which included Belorussia and the Right Bank Ukraine40—were incorporated into the Russian Orthodox Church. Those members of the clergy who did not desire to become Orthodox—amounting to about a quarter of the total—were deprived of their clerical status. Unfortunately, many were even persecuted. The territories that had become part of the Russian Empire later than others naturally had more Uniates. After the decree of religious tolerance issued in 1905, they would be allowed to remain Uniates.

Meanwhile, Galicia remained on the volatile fault line between Catholicism and Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Austrians gave no small trouble to the Orthodox Rusyns, as the Trans-Carpathian people were called.41 While the Poles always maintained a dialogue—albeit an uneven one—with the Russians, the Austrians viewed the Russian element with a cooler malice. The Russian Empire was gaining might, and the pull of a strong, Orthodox monarchy was growing among the Rusyns. Galicia contained a large population of non-Polish people who became polarized between those who considered themselves part of the Russian people—the Orthodox—and those who considered themselves Ukrainians, having a separate identity from Russia—mostly consisting of Uniates. Fearing a separatist uprising, Vienna began to systematically exploit this division, supporting the Ukrainophiles in every way. Thus, efforts were increased to drive the psychological wedge between Russians and Ukrainians even deeper, and Galicia became a stronghold of Ukrainian nationalism, as it is even today.

Once an instrument of Polish domination, the Greek (ByzantineRite) Catholic Church now became an instrument of this rising Ukrainian nationalism. Austria also financed the publication of literature in the language used by Rusyns and Galicians, in order to cultivate a greater linguistic difference between Russian and Ukrainian. Rusyns were more and more called a special nation with their own unique history, and Russia was framed as an enslaver and occupier. These methods of social engineering continued up to the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but they have had a lasting effect on Galicia.

21. World War I, the Fall of Austro-Hungary, and the Rise of Ukrainian Nationalism

When even these Germanic machinations did not entirely work, the Austrians simply killed all Russophiles, even among the Uniates—and there were such Uniates who still considered themselves Russian. In fact, the first concentration camps in Europe were built during World War I—not by Germany, but by Austria, and not for Jews, but for Galicians, Carpatho-Russians, and other Russophile Ukrainians. The most well known of these was Talerhof, near Graz, in southeastern Austria. At first, from 20,000 to 60,000 people died from disease, beatings, torture, and execution. Over 100,000 fled to Russia, and around 80,000 were killed after the Russians retreated. This included 300 Greek Catholic priests suspected of sympathizing with the Orthodox. This planned genocide left a population in Galicia that was now predominantly Ukrainophile.

When, after the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed, western Galicia became part of the restored Republic of Poland. Eastern Galicia and Volhynia declared itself the “Western Ukrainian People’s Republic.” However, after the Polish-Soviet War, the Peace of Riga (March 18, 1921) designated this land as part of Poland, and this was internationally recognized on May 15, 1923. This left a disgruntled separatist population, with even more unrest caused by the Polish government’s intolerance of minorities and its policy of forcible Polonization. Since the many Orthodox Christians in this area could no longer be connected with the Russian Church, which was, in any case, undergoing terrible persecutions at the hands of the Bolsheviks,42 the Patriarchate of Constantinople took over the administration of the Churches in the new states that were formerly part of the Russian Empire, such as Finland, the Baltic states, and Poland. In 1924, it granted autocephaly to the Churches in these states, and the Polish Orthodox Church was born. The Pochaev Lavra, now located outside the Soviet Union, became part of this new autonomous Church.

After the Russian Revolution, Orthodox Ukrainian nationalists decided to form a uniquely Ukrainian Church, separate from the Moscow Patriarchate. They held a synod in Kiev and declared the formation of the “Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.” In 1924, the Patriarchate of Constantinople granted autocephaly to this body. However, after the formation of the USSR, and Ukraine’s incorporation into it in 1921, these Christians began to suffer the same fate as those in other parts of the Soviet Union.43

The long-suffering and patience of a once-Orthodox population in the face of persecutions was wearing thin, and as European war crimes in general became more and more horrific, from Galicia-Volhynia a monster was hatched—a Ukrainian nationalist movement prepared to commit any deed to create an independent, “ethnically pure” western Ukraine. One of the leaders of this movement was Stepan Bandera— whose portrait is now being paraded around western Ukraine by various right-wing groups, and who is considered by them a national hero worthy of emulation.44

In 1929, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (oun) was formed in Vienna. In an illegal propaganda tract, the military arm (uvo) of the oun wrote:

The uvo constitutes a revolutionary organization whose fundamental task is to propagate the idea of a general revolutionary uprising of the Ukrainian people, the ultimate aim of which is the establishment of our own independent and undivided nation.

They considered anyone who leaned either towards Poland or the Soviet Union a traitor. The tract continued:

We must change the psychology of our society and the psychology of the enemies, and influence world opinion. Terror will be not only our means of self-defense but also of [revolutionary] agitation which will reach everyone: our own people as well as outsiders, regardless of whether they desire it or not….

Proclamation: The complete removal of all [occupiers] from Ukrainian lands will create the possibility for and expansive development of the Ukrainian people in the borders of their own nation…. In its internal political activity, the Ukrainian nation will strive to attain borders encompassing all Ukrainian ethnographic territories.45

22. World War II and Its Aftermath

From 1941 to 1944, this policy took the form of extreme ethnic cleansing, first against Polish Jews in the city of Lvov, and later against Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. The first extermination, known as the Lvov Pogroms, took place over a four-week period, claiming 6,000 lives, while the second, known as the Volhynia Massacre, occurred over nearly two years and resulted in as many as 100,000 deaths, mostly of women and children. The atrocities committed by the Ukrainian nationalists against the Poles in the countryside were so sadistic and heinous that they are, simply, unspeakable. Many Ukrainian villagers, both Orthodox and Catholic, were horrified by the crimes and tried to save the Poles; they risked their lives in doing so, and those who were caught were slaughtered along with the Polish victims. 46

To put it briefly, when the German Nazis occupied Poland, the Ukrainian nationalists, led by Bandera, saw this as an opportunity for independence. The Fascist Germans trained them in the mechanics of destroying whole villages. They set the Ukrainians against the Poles, knowing that the Poles would retaliate when given the chance, and all this fit well with the Germans’ plans. The Ukrainian nationalists then implemented their plan of ethnic cleansing.47

In 1939, as one result of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union, western Volhynia was annexed to the Ukrainian SSR. The Pochaev Lavra, now freed from Polish oppression, rejoined the Moscow Patriarchate. The huge numbers of pilgrims that began to visit it, as one of the only monasteries that had not been closed by the Soviets, were actually instrumental in keeping it open. When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, the Germans did not close the Lavra, but did pillage it to a large degree. In May of 1942, under the German occupation, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church was revived. The Pochaev Lavra did not agree to become part of it, desiring instead to be part of the “Ukrainian Autonomous Orthodox Church” which formed in 1941 and remained part of the Moscow Patriarchate. In October 1942, the Autocephalous Church united with the Autonomous Church in a ceremony at the Pochaev Lavra, becoming an exarchate of the Moscow Patriarchate.

When the Soviets won the war, and Galicia-Volhynia became part of the Soviet Union, Stalin was swift to disband the Greek Catholic Church in favor of the Russian Orthodox Church—not of course because he was a conscious guardian of Orthodoxy, but because the Greek Catholic Church was seen as the spiritual leader of the Ukrainian nationalists. The ethnic cleansing in Volhynia had been initiated by the Ukrainian-Nationalist leadership from Eastern Galicia.48 In 1931, the Ukrainians in Galicia had been mostly Greek Catholics.49 There were even cases where these priests had incited and blessed the killings from the pulpit, reading special prayers over the knives, axes, saws, and pitchforks that were to go forth into genocidal action against the Poles. These cases were by no means representative of the Greek Catholic Church as a whole (the Ukrainian Catholic Metropolitan at the time, Andrey Sheptytsky, denounced the violent acts perpetrated by the oun), but the image of Ukrainian Catholic priests blessing the ethnic cleansing of Poles, after centuries of work by the Catholic Church to Latinize and Polonize western Ukraine, points to the staggering complexity of the situation.

23. The Post-war Years

After the war, many of the Ukrainian nationalist leaders, mostly of Greek Catholic background, emigrated—mainly to the United States and Canada. At home, the Soviet authorities were sending whole communities to Siberia and, in a stroke, the Greek Catholic Church was officially gone from Western Ukraine. In 1948, the Soviet state organized a synod in Lvov, at which the Union of Brest was officially annulled. Many churches were simply closed, as were most other churches in the rest of the USSR. For the Orthodox, the Soviet government’s tolerant attitude toward the Church that began during the war came to an end in 1953 with Stalin’s death and the accession of Khrushchev to power.50 Churches that had only recently been reopened were again closed, including the Kiev Caves Lavra.

Conditions remained more or less the same until the late Soviet period. As the thousand-year anniversary (1988) of the baptism of Rus’ drew near, state attitudes began to change, in keeping with the perestroika and glasnost policies of Mikhail Gorbachev.51 By 1988, the government began returning churches and Church property to believers, including the Kiev Caves Lavra. The state even officially apologized for the previous oppression of religion.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and Ukraine became an independent state, the remaining Greek Catholics emerged from underground, and, with moral support from some Ukrainian communities abroad, began to seize Orthodox churches, often using violence against the clergy and congregation.52

In 1990, the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church elevated what had long been its Ukrainian Exarchate to the status of an autonomous, self-ruling Church.

24. Today

This has been but a brief overview of the complex history of Orthodoxy in Ukraine. Mongol Tatar invasions, aggression from Catholic Poland, and internecine struggles have left their mark on Ukrainian Orthodoxy. However, the very fact that people preferred to live (and die) there despite such antagonistic conditions is proof that their faith was strong. The major monasteries—the Kiev Caves Lavra, the Pochaev Lavra, the Kiev Protection Convent, and others—are still Orthodox and still well populated, while there are no Uniate monasteries to speak of. But Ukrainian nationalism, encouraged as always by western “friends,” sees the Russian Church as a foreign occupation force, and has, even from the beginning of the twentieth century, produced a highly confusing variety of Ukrainian Orthodox schisms, the latest of which is the so-called Kiev Patriarchate, led by Philaret Denisenko.

When Patriarch Pimen of Moscow and All Russia reposed in 1990, Metropolitan Philaret (Denisenko) of Kiev became the Locum Tenens (temporary substitute). He was not elected Patriarch, but he would have continued to serve in the Moscow Patriarchate if the president of the newly independent Ukraine had not “strongly suggested” that he become the head of a Ukrainian national Church, formed and supported solely by the Ukrainian government. When the synod of the Moscow Patriarchate learned of his intentions, they offered him a diocese in Russia, but he refused, and remained in Kiev. The Moscow Patriarchate was also concerned about information that Denisenko had for a long time been living with a wife and children. Philaret decided to take up the offer of support from the new Kiev government to head a Ukrainian autonomous Church, but he first had to come to terms with an existing, “autocephalous Church” based in Lvov.53 That “Church,” in fact a combination of two different “autonomous Churches,” was then approached by Philaret. Philaret invited “Patriarch” Mystislav of this “Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church” to Kiev, giving him lodging in his own home.54 There, in Philaret’s home, Mystislav died at age ninety-four, and Philaret, who had, in effect, been running the Church, became the new “Patriarch.” This caused a new schism within that “Church.”

Metropolitan Vladimir (Sabodan), head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) from 1992 to 2014 In April, 1992, there was a hierarchical council of the Russian Orthodox Church, at which twenty bishops from the Ukraine (eighteen of whom had the right to vote) participated. A major topic was the situation in the Ukraine and the status of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—a discussion in a venue that would free the Ukrainian bishops from all inhibition or pressure from the Ukrainian authorities. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainian participants voted against complete independence for the Ukrainian Church, because it would then be forced to struggle against “Uniate aggression” all by itself, without any support from its like-minded fraternal Church, while it was obvious that the schismatic “Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church” was unlikely to cease its own divisive and politically charged activities. The majority of Ukrainian bishops disavowed the signatures they had placed upon a declaration of autocephaly accepted in Kiev under admitted pressure from Metropolitan Philaret and the Ukrainian government.55 Metropolitan Vladimir (Sabodan) was elected head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Metropolitan Vladimir (Sabodan), head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) from 1992 to 2014 In April, 1992, there was a hierarchical council of the Russian Orthodox Church, at which twenty bishops from the Ukraine (eighteen of whom had the right to vote) participated. A major topic was the situation in the Ukraine and the status of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—a discussion in a venue that would free the Ukrainian bishops from all inhibition or pressure from the Ukrainian authorities. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainian participants voted against complete independence for the Ukrainian Church, because it would then be forced to struggle against “Uniate aggression” all by itself, without any support from its like-minded fraternal Church, while it was obvious that the schismatic “Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church” was unlikely to cease its own divisive and politically charged activities. The majority of Ukrainian bishops disavowed the signatures they had placed upon a declaration of autocephaly accepted in Kiev under admitted pressure from Metropolitan Philaret and the Ukrainian government.55 Metropolitan Vladimir (Sabodan) was elected head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Metropolitan Onuphrius (Berezovsky), current head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). Most Ukrainian Orthodox believers are still in the UOC (Moscow Patriarchate), and do not take “Patriarch” Philaret seriously. However, the “Kiev Patriarchate,” with the present Ukrainian government’s support and the use of its paramilitary groups, has taken over a number of churches, including the important St. Sophia Cathedral. “Patriarch” Philaret is regularly shown by the Western media as the head of the Ukrainian Church, with no mention of the legitimate Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Autonomous Church (Moscow Patriarchate), who, since August 2014, has been Metropolitan Onuphrius (Berezovsky). The First Deputy Secretary-General of NATO has even met with Denisenko in an official capacity.56

Metropolitan Onuphrius (Berezovsky), current head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). Most Ukrainian Orthodox believers are still in the UOC (Moscow Patriarchate), and do not take “Patriarch” Philaret seriously. However, the “Kiev Patriarchate,” with the present Ukrainian government’s support and the use of its paramilitary groups, has taken over a number of churches, including the important St. Sophia Cathedral. “Patriarch” Philaret is regularly shown by the Western media as the head of the Ukrainian Church, with no mention of the legitimate Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Autonomous Church (Moscow Patriarchate), who, since August 2014, has been Metropolitan Onuphrius (Berezovsky). The First Deputy Secretary-General of NATO has even met with Denisenko in an official capacity.56

In Volhynia, the churches are roughly divided between the “Kiev Patriarchate” and the Moscow Patriarchate. Volhynia is a mostly rural region, and the local people attend whichever church is closest to them. They generally accept both Churches there out of convenience, but all the monasteries in that region are under the Moscow Patriarchate, and the monastics are firmly resolved to remain in the canonical Church. The Moscow Patriarchate celebrates its services in Church Slavonic, while the “Kiev Patriarchate” uses a translation into modern Ukrainian. The latter grates on the ears of the older generation who know Church Slavonic, but the younger generation is becoming accustomed to the innovation. While the use of Ukrainian in the Church services may seem to many as an innocuous change, it can also be viewed as a continuation of the “linguistic division” and social engineering intended to deepen the rift between Russians and Ukrainians.

In Galicia, the Greek Catholic Church now prevails over the Orthodox Church. The Pochaev Lavra near Ternopil is now constantly under threat from the “Kiev Patriarchate,” and on Holy Thursday 2015, the Ternopil regional council voted to transfer the property of the Holy Dormition Pochaev Lavra to the state.

Although the “Kiev Patriarchate” has made appeals to the Patriarch of Constantinople to be granted autocephaly, this has not happened, and the “Kiev Patriarchate” has not been recognized by any Local Churches as a canonical Church. [This article was written before the current confusing situation, wherein Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople has sent its exarchs to Ukraine to begin the process of granting authocephaly to the schismatic "Church". This move, which has not recieved any support from the other Local Orthodox Churches, caused the Russian Patriarchate to cease commemortion of the Constantinople Patriarch and cease participation in any joint activities. At the time of this posting, the whole affair is still unresolved.]

Meanwhile, the Greek Catholics have continually petitioned an apparently reluctant Rome for their own “Patriarch,” and now their chief hierarch, Sviatoslav Shevchuk, is being called the Patriarch of the Greek Catholic Church. However, he is not the only one coveting that same title, and there have been others in the past. The Moscow Patriarchate has repeatedly protested against this to the Vatican, which has continually reassured the Moscow Patriarchate that it would not sanction a Greek Catholic Patriarchate in Ukraine. However, although the Vatican has not recognized Shevchuk’s title of “Patriarch,” neither has it disbanded the Unia. The Greek Catholics conduct dialogue with the “Kiev Patriarchate,” preferring them to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), which still has the largest number of the faithful in its fold. While the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) remains the most traditional Orthodox Church in the Ukraine, the Greek Catholic Church has become more liberal and westernized, and the “Kiev Patriarchate” is somewhere between the two. Many see the “Kiev Patriarchate” as a bridge to the Unia, and the Uniates, as before, as a bridge to Roman Catholicism.

Map of Ukraine as it looks today.

Map of Ukraine as it looks today.

It must be reiterated that by far the majority of Christian Ukrainians are Orthodox, and that most of these Orthodox are in the canonical Church. Ukrainians are in general a religious people, but this writer perceives a direct correlation between the violence done to the Ukrainian Orthodox people over many centuries by the Latin West and the violent nature of Ukrainian nationalism, an idea that has been taken to its present extreme in Greek Catholic Galicia.

25. Civil War

Tensions in Ukraine continued throughout the post-Soviet period, but erupted into open conflict and civil war in early 2014. After a U.S.-assisted coup, pro-Western, anti-Russian elements took over the government, supported by militant neo-Nazi groups. Pro-Russian, mostly Orthodox citizens in Crimea, fearful for their safety, held a referendum in which they overwhelmingly decided to become part of the Russian Federation. The Russian-speaking eastern Ukrainian provinces of Lugansk and Donetsk (likewise Orthodox in the great majority) refused to accept the coup in Kiev, resulting in an armed conflict between those provinces and the Kiev government that continues to this day.

The various Churches in Ukraine have been deeply affected by the events of the last two [now five at the time of this posting] years. The Orthodox in Western Ukraine have often had no choice but to go to the Uniate churches simply because they lacked their own. Over the years the two Churches have managed to coexist, partly because the Unia was a phenomenon forced upon the masses, though most were not totally convinced. Now the so-called “Kiev Patriarchate” is being forced on many Ukrainians, who are either unwilling to accept it, or who are passively accepting it out of ignorance of Church canons or simply out of convenience—reasons similar to their acceptance of the Unia in its time. The current civil war is exacerbating the tension between the three groups of Ukrainians: those who speak Russian and consider themselves a part of historical Rus’, those who speak Ukrainian but still consider themselves part of Rus’, and Ukrainian nationalists, who dissociate themselves entirely from Rus’ and want the entire Ukraine to do the same. This cannot but influence the religious landscape in Ukraine. And thus continues the tumultuous history of this country of hardworking, poetic, religious people—who gave the world Sts. Anthony and Theodosius of the Kiev Caves, Sts. Theodosius and Lawrence of Chernigov, the writer Nikolai Gogol, and many, many others—for whom all the churches of the Moscow Patriarchate are currently offering up special prayers at the Liturgy—“For peace in the much-suffering Ukrainian land.”

From The Orthodox Word No. 300-301. Used with permission. Follow the link to find the digital version.