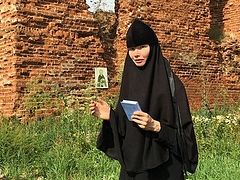

Abbess Nikolaya (Ilina) Igumena Nikolaya (Ilina) is the abbess of the St. Nicholas-Chernoostrovsky Monastery in Maloyaroslavets. A native Muscovite, a scientist with two higher education degrees… How and why did she “trade” pure intellectual tasks for hard physical work, nearly always dirty, in restoring a ruined monastery, and what joy did she find in it?

Abbess Nikolaya (Ilina) Igumena Nikolaya (Ilina) is the abbess of the St. Nicholas-Chernoostrovsky Monastery in Maloyaroslavets. A native Muscovite, a scientist with two higher education degrees… How and why did she “trade” pure intellectual tasks for hard physical work, nearly always dirty, in restoring a ruined monastery, and what joy did she find in it?

How I was baptized

My parents grew up and were educated in the atheist soviet state and were unchurched people, although my great grandmother strongly believed in God and went to church. She became my Godmother.

My father and mother were veterans. My father, Dmitry Vasilievich Korolkov, drove a tank, all the way to Berlin. My mother, Vera Vasilievna, worked in a military hospital during the war, and I was born on May 9, on Victory Day.

I was very ill in infancy and by July I was dying from pneumonia. My great grandmother demanded from my parents: “Let’s baptize the baby or else she’ll die!”

My father was a communist, but he didn’t object. In the 1950s, any Baptism was reported to the authorities, and parents could lose their jobs, therefore they took me to a village church, where I was safely baptized on the feast of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. I recovered and lived.

A child’s prayers

Somehow, from early childhood I always felt that God exists and was accustomed to turning to Him in any difficult circumstances. My Godmother taught me two prayers: “Let God Arise” and Psalm 90. She, my simple, semiliterate Godmother, wrote them down for her favorite granddaughter with mistakes, and that’s how I learned them. I realized and corrected these mistakes only once I was in the monastery.

My mother also joined a monastery later (after my father died) and departed to the Lord as a nun in 2011.

With Mother Nikolaya in Optina

With Mother Nikolaya in Optina

My soul was drawn to God

I liked to learn in my youth and I received two higher education degrees (the Russian University of Transportation and the Moscow Physical Engineering Institute) and worked as head of the laboratory at the Scientific Research Institute while I was finishing grad school. While I was preparing to write my doctoral dissertation, I was studying philosophy and I was already thinking seriously about God and the meaning of life.

In those years, we had the required courses of “scientific atheism” and “scientific communism,” but the human soul was still drawn to God.

The rebirth of Danilov Monastery

In 1983 began the rebirth of Danilov Monastery. It was closed in 1929, the churches and necropolis were destroyed, and a monument to Lenin was erected in the monastery courtyard. The godless authorities also set up a shelter in the monastery for children whose parents were shot at the Butovo firing range. The orphans often got sick and died in the shelter, and they were buried along the monastery walls.

Danilov was the first monastery in Russia that was returned to the Russian Orthodox Church by the soviet authorities (not counting the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, which was transferred to the Church immediately after the war).

The Lord led me to the reviving Danilov Monastery, and I felt such power, such grace! I had days off from my academic and doctoral work, and I started spending them in the monastery. I prayed. I washed the floors. One of the fathers (now an Optina schema-hieromonk), knowing about my profession, said of me: “See what kind of people have come to us!”

And then he saw me with a full bucket.

Optina Hermitage

Optina Hermitage, 1988 In 1988, Optina Hermitage was returned to the Church. The ancient monastery lay in ruins. I went there in July 1988 and then started going there constantly. One of my friends was working there, cleaning the church. One time when she was getting to ready to go on vacation she asked me to fill in for her. I stayed to clean the church, and after that my life became closely connected with Optina.

Optina Hermitage, 1988 In 1988, Optina Hermitage was returned to the Church. The ancient monastery lay in ruins. I went there in July 1988 and then started going there constantly. One of my friends was working there, cleaning the church. One time when she was getting to ready to go on vacation she asked me to fill in for her. I stayed to clean the church, and after that my life became closely connected with Optina.

My first spiritual guide was Fr. Polycarp (Nechiporuk) (now an archimandrite and spiritual father of the Shamordino Kazan-St. Ambrose Monastery). I had met him at Danilov Monastery, and then he and Archimandrite Evlogy (Smirnov) transferred to Optina. Archimandrite Evlogy (now a retired metropolitan) became the abbot of the Optina Hermitage and Fr. Polycarp the dean.

“Either a dissertation or an apostolnik”

After Optina, they started restoring the convent in Shamordino, founded by St. Ambrose of Optina, and Fr. Polycarp was soon blessed to go there as builder and spiritual father. He was very grieved by this, and St. Ambrose himself even appeared him and comforted him.

Like many other of Fr. Polycarp’s spiritual children, I followed him to Shamordino to help him. Many later quit, some were sent away, and I remained to work.

I took my first vacation from the Institute, then my second, and when I had no more vacations left, I quit. Elder Schema-Archimandrite Mikhail (Balaev) (1924-2009) from the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, the future spiritual father of our Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, told me: “Choose: either a dissertation or an apostolnik.”[1]

And I was already well aware that academic work didn’t interest me anymore, that I wanted to be with God.

Shamordino, April 1988. Kazan Cathedral

Shamordino, April 1988. Kazan Cathedral

Obedience as a steward

A month later I was appointed steward of the reviving Shamordino Monastery, although I wasn’t even dressed in a cassock yet. Then they tonsured me as a riassophore with the name Euphrasia in honor of the holy Martyr Euphrasia of Nicomedia.

Much work stood before us: The main monastery church—Kazan Cathedral—stood without any domes, trees were growing on the rotted roof, and there were combines parked in the altar. The hospital building, the trapeza, and all the other monastery buildings were also on their last legs; locals had been living in the residential buildings for a long time, and the brick building erected around the former cell of the great Elder Ambrose of Optina housed a grocery store.

The first sisters of the monastery, mostly city dwellers, had to live without heat, without running water and other amenities. With their own weak female hands they restored the ruined churches, cleared the rubble, dug the foundations, stored firewood and hay for the livestock, and fulfilled a number of other menial tasks.

How the nuns were “well-settled”

The reviving monastery was very poor, but there were even poorer old women from the village of Shamordino who begrudged us. We told them we were bringing some donated wood to the monastery, and they gossiped: “Look how nice everything is arranged for these nuns: They do nothing, and people bring everything to them!”

To this we advised them: “If you prayed, they’d bring things to you too.”

School of humility

As the steward, I had to organize the construction and get the cement and other materials. It was a lot of work, and I also had to go through a school of humility, which was, of course, very beneficial for me.

I would go early in the morning на разводку to the construction teams and confidently plan where to send eeryone: one team there, another here, one squad to the right, one to the left… I would go check on them: One team was drunk, another never started working. And I was left standing with my plans, up the creek without a paddle.

Sometimes everything happens completely differently—in the most miraculous manner. In the 1990s, there was no cement to be found. I would go на разводку and berate myself: “What a lousy steward I am! Someone else would have found and done everything a long time ago, and I can’t even find cement!”

Then I went and saw a “cigar” coming—a cement truck. They brought cement!

“Abbatial” obedience

Having given up my career in the world, I never thought of a career in the monastery. I was puzzled, however, by the words of Elder Mikhail. He reprimanded the sister who was living with me in the same cell (now Abbess Mikhaila): “Don’t refer to Nun Euphrasia as a sister, but as a mother!”

One of the favorite tasks for the future Abbess Mikhaila and I from the first days was cleaning the latrines. They were wooden then and usually dirty, and we really wanted them to be clean. We also had our own “greed:” We really wanted to acquire more grace, and after all, every monastic knows that the heaviest menial obediences teach the soul to humble itself, and that means to attract the grace of God.

When Abbess Nikona (Peretyagina) found out how we were secretly laboring, she scolded us, saying: “You willfully took the ‘abbatial’ obedience for yourself, since according to the tradition of the old monasteries, cleaning toilets was for those who were designated as abbots or abbesses.”

How you have to live in a monastery

One time we went to see Elder Mikhail at the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, and he told us: “You have to live your entire life in the monastery as if it’s the first day you’re there!”

We objected: “Batiushka, come on—our first day we ran around the monastery like fools, kissing every corner of the ruined churches from overwhelming happiness…”

“You were fools before men, but to be that way before God is the most important thing! So, now try to remain such fools your entire monastic life!”

Prayer before a wonderworking icon

Once an Optina hieromonk was invited by Archbishop Clement (now the metropolitan of Kaluga and Borovsk) to go to the Gorny Monastery as the spiritual father. He offered for me to go to Gorny with him and thus he introduced me to Vladyka Clement.

Soon after that, I had to go from Shamordino to Kaluga for some steward business. I had a custom: During trips to Kaluga I would always try to stop by St. George Cathedral and venerate the wonderworking icon of the Kaluga Mother of God. I stepped into the cathedral yard and saw there the very Optina hieromonk. He told me: “They won’t take me to Jerusalem, but Archbishop Clement wants to meet with you. Just wait for me, until I’m free.”

While I was waiting, I went up to the candle desk and ask them to give me an akathist to the Kaluga Icon of the Mother of God. They gave me the seventh issue of the journal “Orthodox Christian” from 1991 with the akathist.

I opened the journal and a note caught my eye: St. Nicholas-Chernoostrovsky Monastery is open--the same monastery where the sisters and I now labor.

I approached the wonderworking icon of the Mother of God and began to pray, and suddenly a lampada started dripping right onto my head. When I went to the candle desk to return the journal, they gave it to me.

St. Nicholas-Chernoostrovsky Monastery in the years of ruin

St. Nicholas-Chernoostrovsky Monastery in the years of ruin

Unexpected tears

When I approached Vladyka Clement, he, absolutely unexpected for me, offered: “The old monasteries are being revived and there aren’t enough inhabitants or possible leaders. Wouldn’t you like to be an abbess in a monastery that’s being revived?”

“Forgive me, Vladyka. I don’t want to!”

“Why?”

“Because I can’t even answer for myself as I should before the Lord, let alone for others…”

Then he said some words to me that were terrifying at that time: “And what if we use our archpastoral authority to put a cross on you and make you an abbess?”

I was so scared that I started crying.

As I later learned, Vladyka cannot endure women’s tears. He didn’t say anything else to me and immediately escorted me out, but, as I now understand, he began to pray. And everyone knows that our Vladyka’s prayers are very strong.

St. Nicholas Church at the Chernoostrovsky Monastery

St. Nicholas Church at the Chernoostrovsky Monastery

Now be a cook

This conversation happened on Ascension, and by Dormition, they had sent me, the Shamordino steward, to be a cook at the diocesan administration. I thought to myself: I refused the abbacy, now be a cook.

But Vladyka obviously just wanted me to, on one hand, be humbled, and on the other, to learn better.

You can’t refuse the abbess’ cross

In response to my story about Vladyka’s proposal, Elder Mikhail said: “You can’t refuse the abbess’ cross, otherwise you will face great temptations!”

Then Vladyka called me a second time and offered: “Let’s continue our conversation.”

But I was already “smart” and answered: “Vladyka, I still don’t want to be an abbess, but I am afraid to refuse.”

Then I confidently added: “And it seems to me it’s not the will of God.”

Vladyka Clement offered me Kazan Monastery in Kaluga. Then some problems began in the reviving Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas men’s Monastery and Vladyka had to close it, but he sent me to revive it as a convent.

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, 1992

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, 1992

First trip to Maloyaroslavets

When I first arrived in Maloyaroslavets, I really didn’t like the ruined Chernoostrovsky Monastery: There was a terrible mess everywhere; nothing was like my monastery (and I really loved Shamordino).

We arrived late in the evening; it was already dark, and behind the ruins and heaps of garbage I didn’t even immediately see the large St. Nicholas Cathedral. And no wonder: It was submerged in darkness and adorned from top to bottom in rotten wooden scaffolding, and inside the wind was blowing. At that time, only the small Korsun Church was active and it was heated by coal. The majority of the surviving monastery buildings lay in ruins. Whole packs of hungry stray dogs were running and howling around the monastery.

Is this how people usually imagine the monastery of their dreams? And I thought: “Will this be my whole life?!”

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, 1991

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, 1991

How I turned to the Optina Elder Moses for help

Everyone discouraged me: “Where are you going?! Where are you going in Maloyaroslavets?!”

I was walking along, and suddenly I was given a book. I opened it—the life of the Optina Elder Moses, the older brother of Elder Anthony, who was sent to be the abbot of the Maloyaroslavets Monastery.

I began to pray: “Dear Elder Moses, tell me: Is it God’s will for me to become the abbess in Maloyaroslavets?”

I opened the book and read the letter of Elder Moses to his brother: “If they call on you to be the abbot in Maloyaroslavets, treat this with all care and humility.”

Prayer to St. Ambrose of Optina

I fervently prayed to Venerable Ambrose of Optina, asking the saint to send me some sisters, at least a few, at least five people, ten, fifteen, and he mercifully answered my prayer: About thirty young girls from Optina came to our Chernoostrovsky Monastery at the same time. Many of them were Muscovites, with higher educations.

The Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Convent was opened by decision of the Holy Synod on April 2, 1992.

Pray and work

The residents of Maloyaroslavets, brought up, like all of us, in the years of soviet godlessness, could not understand how you could trade your life and successful career in Moscow for menial tasks in a ruined monastery in some remote place. They came up with many theories, one of which was that the sisters who had gathered there had actually been arrested and whom the authorities had given the choice: Either go to jail or rebuild the monastery.

After all, it’s very hard for a non-believer to imagine that someone could willingly, by his own desire, come to ruins, filth, and a lack of basic household amenities.

Nevertheless, we went. In fact, the sisters, accustomed to comfortable city living, really had nowhere to live in the then-ruined monastery. We had no hot water—and what hot water? There was no water at all—only in the spring. Then we were given some ceramic heaters, which are usually used in barnyards.

But we did not despair—there was no time for despair. We had to pray and work: roll up our sleeves, install water and heat in the buildings, and restore the beautiful cathedral and wonderful ancient monastery.

His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II and Archbishop Clement at the monastery, 1999

His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II and Archbishop Clement at the monastery, 1999

Twenty-seven-year path

Our monastery is now twenty-seven years old, and of course many things have happened over the years: temptations and sorrows, joys and spiritual revelations.

Perhaps I will tell you about that next time.

God bless all the readers of OrthoChristian.com!