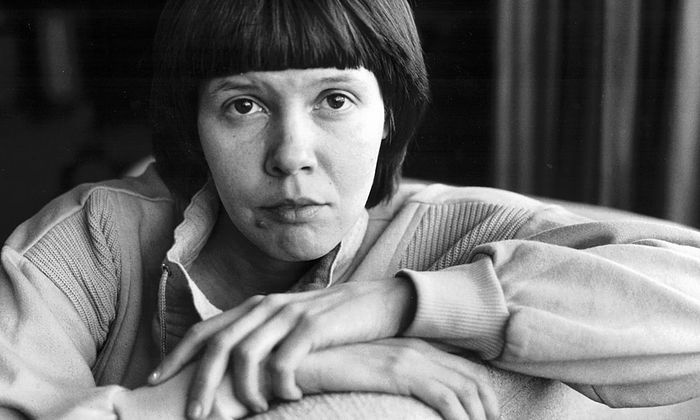

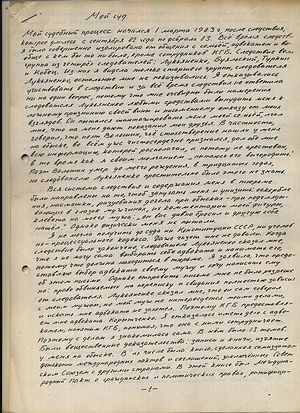

Irina Ratushinskaya was a Russian poet and writer, an Orthodox Christian and at the same time, “an especially dangerous political criminal”. Because of her poems, in 1983 she was sentenced to seven years in a maximum security prison followed by exile—a five year term, the harshest prison sentence ever given to a woman under a political article after Stalin’s death. The year was 1983, which was not one of the Red Terror years,[1] nor of the Stalinist repressions[2]. The Soviet Criminal code contained no such article under which one could be persecuted for “writing poems”, nor for “signing human rights letters”. How could a woman be jailed without breaking any laws, even if she was, without a doubt, not pleasing to the atheist regime? This manuscript written by Irina Ratushinskaya was saved; it describes how her trial was conducted, how the witnesses were intimidated, how even the dead gave evidence against her and the living lost their right to speak.

Sergey Gerashenko, the son of Irina Ratushinskaya

Irina Ratushinskaya’s book, Grey is the Color of Hope, published in 1988 after she and her husband had emigrated to the U.S., describes her ordeal in the Soviet “strict regime” prison camp, where she was incarcerated after sentencing for four years.

***

My court hearing began on the first of March 1983, after a criminal investigation that lasted from September 1982 until February 1983. All the time during the investigation I was completely isolated from communicating with my family, my lawyer, or anybody else, expect KGB employees. The criminal investigation was lead by a group of four government investigators: Lukyanenko, Bujalskij, Turkin and Kobez. Out of all of them I have only met the head of the group, the investigator Lukyanenko; the rest didn’t show themselves to me. I refused to take part in the investigation and did not answer a single question during throughout the investigation, because the intention of the investigator Lukyanenko were obvious to me from the outset—that is, to extract from me by any means possible a false admission of guilt and a written retraction of my views. He tried to blackmail me using my family, and he lied to me that my friends were giving evidence against me. In particular, he said that the poet Voloshin (they found his poem on me when they searched me), made a confession and provided all the information that he possibly could on me, and that is why he was not arrested. But by being silent, I was supposedly “trying to protect him”.

“The investigator said that the poet Maximillian Voloshin made a confession and provided all the information that he possible could on me...

The poet Voloshin died in the 1930s, before I was born, but it is forgivable for the government investigator Lukyanenko to not know this fact.

The whole set up of the investigation and my remand in custody were aimed at scaring and humiliating me: insults, sneers, full undressing during searches—with peeping men, their comments about my figure, and slander against my husband. They said, “He dumped you and found somebody else.” Still, physically they did not torture me.

Before the trial I could get a copy neither of the USSR Constitution, nor the Criminal-Procedural Code. They didn’t even give me newspapers. When the investigation was over, the government investigator Lukyanenko told me that I could not choose and hire a lawyer myself, because I must remain in custody. I stated that I will give the option to choose a lawyer to my husband and that I want to write a letter to him to tell him that. However, I was forbidden from sending the letter: the right of the accused to any correspondence and meetings are entirely up to the government investigators. Lukyanenko told me that he himself spoke to my husband and that my husband was no longer interested in my affairs and didn’t want to look for a lawyer. That is why the KGB is providing me with a lawyer, Koritchenko. I refused to deal with the lawyer hired by the KGB, knowing that she collaborates with them. That is why I got to know the legal case myself. My case had thirteen volumes. There was physical evidence: writings and books taken away from me when I was searched. One of them was a self-published book, photocopies of international pacts and agreements between the Soviet Union and other countries. In that book, there was an international pact about human and political rights, ratified by 35 countries including the USSR. The pact evidently showed that the internal laws of a country cannot contradict the international pact, so I’ve decided to build my defense on the only available document to me, even though the document was listed as part of the physical evidence against me. I made notes from that book and used them during the trial and later when I put together my appellate complaint to the Supreme Court to re-examine the law as was decided by the trial court.

However, when I was brought to the courtroom, it turned out that not a single person out of those who knew me were let in, including my family. I sat alone in the courtroom, guarded by three KGB workers, and then I heard my mother screaming in the corridor: “Let me in, my daughter is being judged there!”

However, when I was brought to the courtroom, it turned out that not a single person out of those who knew me were let in, including my family. I sat alone in the courtroom, guarded by three KGB workers, and then I heard my mother screaming in the corridor: “Let me in, my daughter is being judged there!”

But they didn’t let her in. Instead, thirty people entered the courtroom led by a man dressed in civilian clothes. They conducted themselves in an orchestrated manner and obeyed the man so that when he told them—they sat where they were told to sit and during intervals they left the courtroom when they were commanded to leave. I knew that it was a typical KGB trick: The hearing was supposed to be open, but it was the KGB that decided who was to be present and who was not and so they filled the courtroom with their own people. There were exactly as many people as there were seats in the courtroom.

I declared to the court that I refuse to be defended by the KGB appointed defense counsel Koritchenko and want to defend my case myself. Koritchenko asked for the court to decide whether she may leave, but should the court indeed appoint her as the defense counsel, she would submit herself to the court. But the judge Zubez said that the court cannot let me defend myself, “as I am not qualified”, and obliged Koritchenko to conduct my defence instead of me. So, in the end it came down to me not being able to defend myself, and as for Koritchenko—she was silent almost throughout the whole process. She opened her mouth only twice—once she asked the court to draw one more witness but did not insist on that being done. And once she asked my student, an eighteen year-old witness:

—Why didn’t you report the accused to the party bodies earlier?

“Why didn’t you report the accused?” my defense counsel asked my student, an eighteen year-old witness.

I addressed the court with the statement that I believe that the trial was illegal for the following reasons. That according to the international pact which was signed by the USSR, the court had no legal right to prosecute me for expressing my views, convictions and also for my poems, even if everything that I wrote gets distributed regardless of countries’ borders. I have never conducted the propaganda of war, terror or racist hate crime, so my case fell under the relevant article of the protections of the pact entirely. Nonetheless, I was left without the right of defense. The government prosecutors did not call people to appear as witnesses in whose defense my husband and I have written open letters—neither the Nobel laureate Andrei Sakharov, nor Vladimir Kisilik, who was planning to immigrate.

The investigation was clearly conducted in an improper political manner and the accusations were largely based on the legal principles of “slander”, a term repeated 150 times during the trial. But the elements of slander had not been proven a single time and the investigation did not even check as to what extent the facts stated in those human rights documents I signed were factual. Moreover, it is not appropriate to apply the term “slander” to fictional writing, as it contains no references to actual names and facts.

It was announced that the trial is to be conducted in public, yet it was closed to everybody who knew me and in reality was only open to those selected by the KGB. If there was not enough space because of the KGB workers, they could have found a larger courtroom and brought in additional chairs.

On the basis of what I just described I demanded that the Nobel laureate Andrei Sakharov be brought in as a witness, to have the right of defense returned to me, and let the courtroom be open to all those who want to be there. Should that not be done, I said that I believe that the very fact of such a trial is an illegal act and I refuse to take part in the breaking of the law in any shape or form. Nonetheless, I noted that I was reserving the opportunity to make a final statement.

As I was making this speech, judge Zubez interrupted me a number of times, ordered me to be quiet and to sit down. However, each time he addressed me with questions, I began this speech again from the very beginning and on the sixth time the court had to hear me out. But my speech was not taken into account and my demands were not satisfied. The trial continued, but I no longer took part in it and didn’t respond to the questions the judge asked me.

The first day of the trial was dedicated to a repetition of the alleged crimes, which the prosecutor listed verbally, soliciting informally my responses to the accusations. The judge Zubez told me that by being silent I “was making the situation worse for myself” and that they were expecting “sincere remorse” from me.

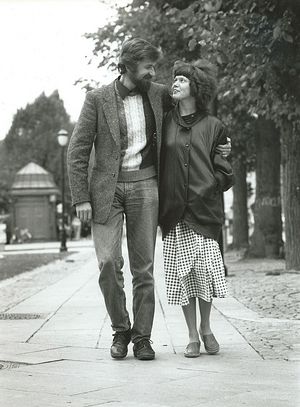

Irina Ratushinskaya with her husband, Igor Gerashenko The questioning of the witnesses took place under the same circumstances. My husband was called forward as a witness. He declared that he considers the court to be illegal because I had no right of defense. It turned out that the government investigator told him that the lawyer cannot receive access to me before the end of the investigation and the family will be informed once the investigation is over. However, after the end of the investigation he deceived my husband, insisting that the investigation was still ongoing and that the date of the trial was not yet known. My husband found out about the day of the trial only when he was called to attend the court as a witness. He petitioned for the trial to be postponed until after he signs a contract with a lawyer and after the lawyer gets through thirteen volumes of my case. But the request was refused. On this basis and out of moral and ethical consideration, he refused to answer questions about me or anybody else, declaring only that it was the judges who were criminals and not me. He demanded to remain in the courtroom as is allowed by the Soviet law, even if that means that he must sit in the only remaining empty place in the courtroom—on the bench of the accused next to me. But the judge ordered him out of the courtroom. When he was at the door he shouted to me that I have the right to examine the protocol of the trial and note written remarks to the protocol.

Irina Ratushinskaya with her husband, Igor Gerashenko The questioning of the witnesses took place under the same circumstances. My husband was called forward as a witness. He declared that he considers the court to be illegal because I had no right of defense. It turned out that the government investigator told him that the lawyer cannot receive access to me before the end of the investigation and the family will be informed once the investigation is over. However, after the end of the investigation he deceived my husband, insisting that the investigation was still ongoing and that the date of the trial was not yet known. My husband found out about the day of the trial only when he was called to attend the court as a witness. He petitioned for the trial to be postponed until after he signs a contract with a lawyer and after the lawyer gets through thirteen volumes of my case. But the request was refused. On this basis and out of moral and ethical consideration, he refused to answer questions about me or anybody else, declaring only that it was the judges who were criminals and not me. He demanded to remain in the courtroom as is allowed by the Soviet law, even if that means that he must sit in the only remaining empty place in the courtroom—on the bench of the accused next to me. But the judge ordered him out of the courtroom. When he was at the door he shouted to me that I have the right to examine the protocol of the trial and note written remarks to the protocol.

The witnesses who were called to come forward were the Grishins couple and our friend Ostromogilskiy. All three refused to give evidence citing that the trial itself was illegal, that I did not have a right to defend myself and that it was a closed trial. The judge threatened the three of them with problems at work and openly conducted himself rudely. He started criminal proceedings against the three of them as they refused to give evidence. All three were sentenced to six months of forced labor.

The remaining witnesses were either my students, colleagues, or KGB workers. The witnesses Kozdoba, Ostapovsky, Lejenin, Rybak, Okondza and Sergeeva were the informants. My arrest had been preceded by three years of surveillance by the KGB; I knew that they were trying to provoke me and for that reason I did not engage in open conversations with them.

“The witness Sergeeva: I saw her only once before my arrest—when she came to us to conduct a search together with the KGB workers”

I never spoke a single word to the witness Sergeeva: I saw her only once before my arrest, when she came to us to conduct a search together with the KGB workers—the purpose of her presence then was not clear to us. During the search she tried to provoke me and my husband with insults, rummaged through our things, even threatened me but we did not react to these provocations. During the trial she also said expletive words addressed to me and my husband, tried to insult me, and yet the judge Zubez laughed at me: “Why are you pretending to be a simpleton? Can’t you hear what they are saying about you, and yet you don’t refute it? Why are you holding your tongue?”

The witness Ostapovsky mostly talked about how he spilled blood in Afghanistan (he was talking about his own blood), whilst people like me were undermining the foundations of the state.

My students and my work colleagues at the kolhoz[3] tried to defend me in every way they could. But they did not know the laws and nothing came of their efforts. So they talked about the government investigator Buyalski pressuring them to give evidence, threatening them with problems at work and at university. At the same time, he was saying, “In conversation with you, Ratushinskaya said such and such,” and he demanded that they testify to it in writing. It wasn’t a hard thing to do as my students were all seventeen and eighteen year-olds, and they were in their first year of study at university. None of them knew that during the investigation they had the right to refuse to give evidence under pressure.

The discussions went along these lines:

Eighteen-year-old Monaenkova:

—Ratushinskaya didn’t say anything special to me. The investigator did not write it down as I said it.

Judge Rubez:

—Then why did you testify to it in writing? Do you know what happens if one provides false evidence?

Monaenkova:

—But the investigator Bujalkovksi told me to sign it.

Zubez:

—Well, was he wrong in telling you that? Did you have such a conversation with Ratushinskaya or not?

Monaenkova:

—But she only said she talked about things that you can overhear while standing waiting in any queue. That is not slander.

Zubez:

—I am not asking you whether it is slander or not. I am asking you whether she talked to you about Afghanistan. Did she?

Monaenkova:

—I do not remember.

Zubez:

—How can you not remember? Have you got a bad memory? How were you admitted to the university then? How can you be a student if you’ve got a bad memory? Interesting, do they know at your university that you are serving as a witness on a political case? We should inform them how you conduct yourself here. Or do you share the views of the accused?

Monaenkova:

—I do not share them.

Zubez:

—Oh, so you acknowledge that she has anti-Soviet views? So why are you, a komsomolka,[4] a student, trying to blanch over the fact?

Monaenkova is crying.

Zubez:

—Witness Monaenkova, do you confirm your testimony that you have signed at the investigation? Or did you give false evidence?

Monaenkova:

—I confirm my testimony.

She left the courtroom in tears, hiding her eyes from me. But can you judge a student who can get kicked out of university after a single call from the KGB, or judge her for not knowing how to conduct herself in a way that would cause me no harm? In a similar spirit other witnesses were questioned, who were not KGB informants. An interesting fact was that despite the interrogation of people from the team I worked with before my arrest, the court nonetheless included into my sentencing as an aggravating circumstance the fact that “from April 1979 I haven’t worked anywhere”—despite the fact that they arrested me as I was on my way to work.

“My husband’s sentence was added onto mine, in the hope that I would object to it and thus give them the required testimony against him

Another amusing aspect of the trial was that they added my a charge against my husband for writing an article entitled, “Administrative arrest—a fight against hooliganism or an economic necessity?” That article was published under his name in the Informational Bulletin of the Free Inter-professional Union of Workers.[5] My name was not listed [as a co-author of this article] as my husband wrote it all by himself. This fact was known to the investigation and to the court, as the article was part of the evidence. However, it seemed that they expected me to react by expressing my protest in that I was being sentenced for my husband’s article. But that could have been interpreted as me giving evidence against him and the court could have used it [by opening a case against him]. Yet since I was quiet and my defense counsel was idle, the prosecutors couldn’t remove the accusation themselves. So this accusation remained in my sentencing. Yet there is no big mistake in that as the article tells the truth and if I had any claim to it, I would have gladly signed my name under it.

On the same day, the second of March, the court examined the evidence. The process took one minute and forty five seconds—I set the time by the wristwatch of the KGB security guard standing close to me. It consisted of the judge and two jurors taking the relevant volumes of my case from a stack on one side of the table and putting them into a stack on the other side of the table, without even pretending to read them.

“Well, we know all that,” said Judge Zubez.

The prosecutor Pogoreliy made a speech about how Soviet society needs to be constantly vigilant. At the same time, he made references “ to comrade Andropov[6] himself”. He demanded that the court give me the maximum sentence possible according to Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and according to Part One of Article 70 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. The defense counsel Korytchenko was also ordered to say something, and she declared that, despite conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, I had not enticed anybody onto the path of crime, and on that basis the court should find me innocent.

As planned, I demanded to make a final statement. I intended to voice all the texts for which I was incriminated, beginning with poems, and then declare once more that they had no right to judge me for voicing my views. I began by reading the poem, “Motherland”, which was the first listed accusation among many. However, I was interrupted at the very first line. Judge Zubez shouted:

—Be quiet! We will not let you cite libel! What do you ask of the court?

Me:

—There is nothing to ask of the court. But I have a right to make a final statement and wish to make it.

Zubez:

—Since you not asking anything then I deprive you of the right to talk.

That’s how the second day of my trial ended.

On the third of March there they pronounced my sentencing. Again, no one was allowed into the courtroom. I listened to my sentence and I was taken back to jail. On the fourth of March, on my birthday, I was given the copy of my sentence. I knew that I had a right to familiarize myself with the protocol of the trial, but didn’t know under which article of the Criminal-Procedural Code, and without it I could not write the relevant claim [to ask for the protocol]. Unexpectedly, my defense counsel Koritchenko paid me a visit to persuade me to plead guilty in my appeal to the Supreme Court. I saw that she had the Criminal-Procedural Code with her and I demanded to look through it. I noted down the necessary articles of the Code and let Koritchenko go; she was very nervous that I got hold of the Code. There was no law forbidding convicted prisoners from reading the legal code. But there were secret injunctions and we both knew it.

When I got hold of my trial protocol, it turned out that there was no written transcript of the proceedings and that the protocol was not in line with what really happened during the trial.

“I got hold of my trial protocol. But it was not in line with what really happened during the trial”

The protocol did not contain the text of my speech to the court, neither that the right to make a final statement was taken away from me, nor the phrases by witnesses that the defense (had it existed) could have used. I wrote my remarks to the protocol listing twenty-three points and sent it back to the court, however none of the remarks got accepted. After all, the cooking up of the protocol was not cooked up just so that I could damage their paperwork.

After their trial, prisoners are allowed a half an hour meeting with a relative of their choice. But the choice was made for me by the KGB—my husband was categorically denied a meeting with me and instead, they set up a meeting with my mother-in-law. My mother-in-law passed me my husband’s advice to write an appellate complaint to the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialistic Republic. I listed all the violations I had noted during the investigation and the trial and demanded an open court investigation with a right of defense. I submitted the appellate copies of my courtroom speech and my remarks to the protocol. But not even I was not allowed to attend the Supreme Court hearing. Three weeks later I received a written reply that the Supreme Court had reviewed my case and the sentencing was not overruled. There were three signatures under this response: Tchaikosvky, Lyaskin and Shidlovski.

When I was being taken away from the Kiev KGB jail to the prison camp, the copy of my sentencing and all my notes were taken away from me. For three years I demanded that my sentencing be returned to me and only in July 1986 did I get it back. The text of my speech during the trial, my appellate complaint, and my remarks to the protocol were never returned to me. Now the copies of these texts are kept in two places: the KGB archives in Kiev and in the archives of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.