The wonderworking Albazin icon of the Mother of God, “The Word Was Made Flesh”, from the Church of holy Archangel Michael, village Vysokoye of the Pestravka district, the Samara province. A local historian I knew asked me:

The wonderworking Albazin icon of the Mother of God, “The Word Was Made Flesh”, from the Church of holy Archangel Michael, village Vysokoye of the Pestravka district, the Samara province. A local historian I knew asked me:

“Do you know what became of the Albazin icon of the Theotokos?”

I looked so perplexed that she added:

“It was you who wrote about the demolition of our cathedral. That icon was one of its main holy shrines. Its second name is ‘The Word Was Made Flesh’. Don’t you know that?”

I had to confess that I knew nothing about that icon.

The historian smiled ironically and moved away without asking any more questions.

True, I did write about our Resurrection Cathedral which had once dominated the center of Samara and could be seen from the Volga River miles away. The cathedral had been the main attraction of Samara and the pride of the whole Volga region[1]. The edifice took twenty-five years to build, but it took Bolsheviks as many as five years to “enthusiastically” destroy it. It had truly been built to last!

I thought that since all the icons had been burned on a day “specially designated” for this purpose, the “obscure” Albazin icon had no chance to survive.

I got back home from that half conference-half meeting, turned my laptop on and read the available information about that icon. I learned that the icon derived its name from the Albazin Fortress in Priamurye[2], which was founded in 1650 by the prominent Russian explorer Yerofey Khabarov. The Mother of God twice saved the fortress from the Chinese forces that besieged it. Through the intercession of the All-Holy Virgin, in the 1680s the Chinese imperial forces suddenly withdrew from the beleaguered Albazin where the Russian soldiers were praying and preparing for death, just as in 1382, Tamerlane, who had been advancing on Moscow with his formidable army, was suddenly pulled away.

The wonderworking icon was brought to Samara by Bishop Guriy (Buratovsky), who in October 1892 was assigned to the Diocese of Samara. While seeing the bishop off, the parishioners of Blagoveshchensk who loved him dearly, with tears in their eyes presented the hierarch with the cathedral’s icon so that it could protect him on the banks of the Volga, just as it had preserved him on the banks of the Amur. In addition, as a token of their esteem and love they also presented him with a copy of the Albazin icon for private prayer.

Having read many other remarkable details about the Albazin Fortress, Bishop Guriy and numerous miracles wrought through the holy icon, I got to the following point:

“By decree of the Holy Synod of August 24, 1895 no. 4142, the Russian Church blesses the annual commemoration on March 9 of the ancient icon of the Mother of God, called, ‘The Word Was Made Flesh’, kept at the Blagoveshchensk Cathedral, giving it the name ‘the Albazin icon.’”

I read this for the first, second, and third time until at last it came home to me that March 9 according to the old calendar means March 22 according to the new calendar!

It seemed to me that I knew absolutely everything about March 22 because it is my birthday!

March 22 is the day of the spring equinox, and it is popularly known in Russia as “the arrival of the larks.” On that day my granny used to treat me, a child, to baked pastries in the shape of larks.

It is the feast-day of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, Armenia. I hadn’t known about that before my life in the Church began. In order to flaunt my knowledge in front of my peers I even wrote in an article on the film that Boris Lavrenyov (1891–1959), the author of the famous story, “The Forty-first” (which was adapted to film), must have known about the Forty Martyrs.

And, like a bolt from the blue, I discovered the most important thing about March 22!

And the word was made flesh (Jn. 1:14)—this is in essence the continuation of the first verse of the Gospel of John: In the beginning was the Word (Jn. 1:1).

We often repeat this phrase without understanding that the apostle was not talking about the “Logos” as a literary term: he meant Christ, the incarnate Word of God that lived among us; that’s why “the Word was made flesh.”

The type of representation of the Virgin Mary with the Child in Her womb is called “Orans”, or “Orante”, which can be translated not only as, “She Who is praying”, but also as “the Directress.”

For me personally it meant that the Theotokos has always been my Guiding Star.

No sooner had my ignorance (that I had foolishly bragged about) been dispelled than I dug up far more impressive details about that icon of the Mother of God and the dramatic events associated with it that took place in the 1930s—a period when all aspects of the life of the Church were being destroyed.

There was the thriving Chagra[3] Convent of the Protecting Veil of the Theotokos [now Kirovsky village in the Samara region.—Trans.] in the south of the Samara province. It was famous not only across the Volga region but all over Russia. Fr. Alexander Yungerov[4]], the convent’s spiritual father, was noted for his holy life and the gifts of clairvoyance and healing, so the convent attracted crowds of pilgrims. It was said that even during terrible droughts, heavy rains would always appear as if from nowhere, water the plants of the convent’s gardens, and then stop.

This is what we read about Fr. Alexander in the Samara Diocesan Gazette for 1896:

“There were special, extraordinary gifts of the Holy Spirit for Christians of the early Church of Christ in the age of the Apostles. Perhaps in our times, for the awakening of conscience of those who are weak in faith or seeking the Lord, great figures with special spiritual gifts are necessary as well. These are individuals with the spirit and zeal of the Prophet Elias, such as Fr. John of Kronstadt, the learned Bishop Theophan who lived as a recluse at Vysha, or Fr. Ambrose of Optina. Undoubtedly, one of them is our pastor—Fr. Alexander Yungerov.”

The Bolsheviks laid waste to the convent, expelled the nuns and set up a pigpen on its territory. These are historical facts and not a literary image. After a time even the pigpen lay in ruins. While searching for Fr. Alexander’s grave, I saw “the abomination of desolation” with my own eyes.

But amid tall weeds and waste ground, pious laywomen managed to preserve his holy grave and put a fence around it. Thus in due time, Fr. Alexander’s relics were uncovered. Now they rest at the Iveron Convent in Samara.

Righteous Alexander of Chagra. When I learned that the Holy Protection Convent of Chagra was being revived,[5] I decided to visit it and see the progress of its construction work. Besides, there is the village of Vysokoye close by, where Archimandrite Vladimir (Naumov), a very interesting priest, has served for more than fifty years at the Church of the Archangel Michael (which was never closed in the Soviet era). At last my wish came true and I called on Fr. Vladimir.

Righteous Alexander of Chagra. When I learned that the Holy Protection Convent of Chagra was being revived,[5] I decided to visit it and see the progress of its construction work. Besides, there is the village of Vysokoye close by, where Archimandrite Vladimir (Naumov), a very interesting priest, has served for more than fifty years at the Church of the Archangel Michael (which was never closed in the Soviet era). At last my wish came true and I called on Fr. Vladimir.

The church rector and I were sitting on the veranda of his house and talking. The sun was shining, and our conversation was going smoothly. I received a warm welcome from Fr. Vladimir because I had brought him my book on Metropolitan John (Snychev) of St. Petersburg, who was his spiritual father. He treasured the future metropolitan’s spiritual gifts so much that he would often come to him—first to confess his sins, and then just to relax and go fishing.

Archimandrite Vladimir (Naumov). When our conversation gradually drifted to the subject of convent, Fr. Vladimir brightened up and told me about its last abbess, Mother Agnia (Loginova):

Archimandrite Vladimir (Naumov). When our conversation gradually drifted to the subject of convent, Fr. Vladimir brightened up and told me about its last abbess, Mother Agnia (Loginova):

“Do you know what kind of abbess she was? I was told she galloped on horseback! She saved all the convent’s holy objects that could be hidden here. She was so brave! And what about us? I wish we could inherit if only a tiny bit of their faith and fortitude!”

He was staring at me fixedly through his glasses, screwing up his eyes.

“This is who we should write about!”

“Have the convent’s holy icons survived?”

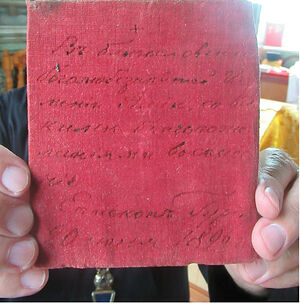

“You’ll see several ancient icons at the church. But there is also a very special one in the altar, it bears the inscription:

'A blessing for the most God-loving Abbess Agnia, with all best wishes for salvation. Bishop Guriy, June 20 1896.’

'A blessing for the most God-loving Abbess Agnia, with all best wishes for salvation. Bishop Guriy, June 20 1896.’

“The icon is called, ‘The Word Was Made Flesh’.”

Once again he looked at me intently, screwing up his sharp eyes.

“What’s the matter with you? You don’t believe? Tomorrow I’ll take it out of the altar after the Liturgy and you’ll venerate it.”

“Thank you, Fr. Vladimir!”

And I told him the same story I have just told the readers, quickly and in a somewhat confused manner.

Archimandrite Vladimir (Naumov) with the icon, “The Word Was Made Flesh”. This icon had been brought to the church by one of its parishioners. That was long ago, so nobody knows how that person had obtained this holy icon. But the fact that it belonged to Bishop Guriy is confirmed by the inscription on its reverse side.

Archimandrite Vladimir (Naumov) with the icon, “The Word Was Made Flesh”. This icon had been brought to the church by one of its parishioners. That was long ago, so nobody knows how that person had obtained this holy icon. But the fact that it belonged to Bishop Guriy is confirmed by the inscription on its reverse side.

And for the umpteenth time in my life I received proof that it is only with time that we learn the most important things, provided that we don’t think too much of ourselves, that we supposedly know everything and have solved all the mysteries. The more you live the more you learn—this is a remarkable aspect of our faith.

And this knowledge is infinite.