As in the previous century, one of the main centers of Christianity and culture in Western Europe in the eighth century was Ireland with its relatively small population, which numbered around 250,000 at most.

Irish monks enjoyed indisputable authority among the people. One of its characteristic examples was the declaration of the “laws of the saints”, which were instituted in monasteries and then adopted by the rulers of the numerous kingdoms Ireland was divided into. The first such law was introduced in 697 by St. Adomnan, Abbot of Iona, and became known as “the Law of Adomnan” (“Cain Adomnain”), or “the Law of the Innocents.” It prohibited the killing of women, clerics and children who did not take part in warfare (that is, noncombatants, to put it in modern terms) and perpetrators were exposed to substantial fines. In 734, “St. Patrick’s Law” was enacted, and in 788 “St. Ciaran’s Law” was proclaimed.

“When the laws were promulgated and amended, the heads of church communities would travel all over regions of Ireland with relics… They would receive gifts from rulers and distribute alms.”1

Saints’ remains were venerated by people as great relics. In 727, a conflict between two clans flared up in Ireland. Hoping that through the prayers of St. Adomnan a truce could be reached, the monks from Iona Monastery brought the saint’s relics to Ireland and visited forty churches that belonged to Iona. And indeed, it became possible to reach a truce very soon. Many people took an oath on the holy abbot’s relics and promised to obey “The Law of Adomnan”,2 who discouraged enmity between people.

In the second half of the eighth century there appeared an ascetic movement that aimed to cleanse Church life in Ireland from numerous abuses. For example, rivalry between the supporters of different monasteries would often result in scuffles and bloody clashes. One of them took place in 764 and turned into a real battle—as a result about 200 people were killed because of false religious zeal. The leading figures of that ascetic movement, such as St. Maelruain, Dublitir and other bishops and abbots, called themselves “Celi De”, or “Culdees”, which can be translated as “worshippers (sometimes “servants”, “companions”) of God”.

St. Maelruain is venerated as the founder and first abbot of Tallaght Monastery near what is now Dublin. He was tonsured at the monastery of St. Ruadan of Lothra. In 774, he obtained lands in Tallaght from the King of Leinster to establish a monastery there and brought the relics of holy martyrs to it. Some Lives call him “bishop of Tallaght”, though there is no solid evidence confirming the existence of a diocese there. St. Maelruain used to say that the three most profitable things for monks throughout the day should be “prayer, manual labor, and study”. During the day they will obtain much profit from reading, writing, and sewing clothes. The rule of St. Maelruain, based on the instructions of the Egyptian desert fathers through St. John Cassian, devotes much attention to fasting, praying and repentance to one’s confessor, whom the Celts called “the soul friend.”3 This rule was also introduced in other Irish monasteries that joined the Culdee movement. The purpose of the rule was to return to older forms of ascetic life in Ireland. Special attention was given to genuflexion and prostration in prayer, the mortification of the flesh and such strict practices as prayer in cold water with arms raised up in the form of the cross, and full abstinence of alcoholic drink… St. Maelruain’s followers, the Culdees, also forbade the practices of “pilgrimage”, or “wandering for Christ” so characteristic of Celts—as well as moving from one monastery to another, sea voyages and settling abroad.4 St. Maelruain reposed in the Lord in 792.

St. Oengus honored and appreciated St. Maelruain, his beloved mentor and teacher, so much that he called him “the great sun of the south plain of Meath”.5 St. Oengus himself composed martyrologies in verse and prose, and the Stowe Missal (containing unique recordings of ancient Irish liturgical texts).6 The Culdee movement attached great importance to Christian education and the enlightenment of the people—monks in particular—producing some of the most educated Western theologians and thinkers of the age. Culdee communities attracted pious laypeople as well. Some groups of laypeople started to form their own small communities. They were like villages, situated in wild, remote areas, and people lived there in piety together with their families, practicing farming and manual work, often praying and singing spiritual hymns (in addition to the participation in Church prayer and the sacraments).

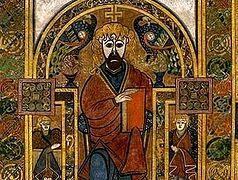

Learned Irish monks generously shared the fruits of their Christian and classical education with people from the Continent; they were sought after at the court of Charlemagne and other Western monarchs. A network of Irish monasteries founded by the Gael missionaries covered the whole Continent. In the eighth century, monasteries inside Ireland were at a high level of contemporary Western Christian culture. Some of the most brilliant examples were book miniatures, remarkable for their striking originality because (unlike Continental ones) they were not influenced by tradition of Late Antiquity. Their distinctive characteristic is the domination of ornamentalism over figurative pictorialism: “A combination of the abstract geometry of the Celts (various spirals and twists) and motifs of the Anglo-Saxon animal style is characteristic of the décor of Irish manuscripts.”7 Another peculiarity of Irish miniatures is their brilliance, the use of bright, pure colors, separated by a strong, sharp-cut outline. Irish artists who illuminated manuscripts would avoid leaving any blank space and cover the whole leaf with a colorful ornament. Figurative motifs are little developed, complying with the decorative message and fitting into the ornament, so the image is always two-dimensional. Most eighth-century Irish illuminated manuscripts are the Four Gospels. Among the most celebrated manuscripts of the age is the Book of Kells, which contains the Four Gospels, and is kept at Trinity College in Dublin. It dates back to the late eighth or the early ninth century. Irish scribes developed a distinct style of calligraphy, based on a synthesis of Roman half-uncial and elements of the Greek practice of writing letters. This easily recognizable script became known as “insular”, and it greatly influenced Anglo-Saxon calligraphy. In some manuscripts, Irish scribes used Greek letters to write Latin texts. Another attribute of early Irish Christians is the reverence with which they held spiritual books. Books were venerated as relics and miraculous properties were attributed to them. According to Svetlana Kovalevskaya:

“Most manuscripts survive in poor condition because they were used for healing people and animals, and even were taken to battles.”8

The Celtic art of the jeweler, of the metalworker and of stone carvers (both insular and Continental) had been known for their high level of perfection since the La Tene Culture. The achievements of ancient craftsmen in art were inherited by Irish jewelers, metalworkers and blacksmiths of the Christian era. The finest workpieces of the eighth century were commissioned by the Church. Liturgical vessels and other items for church use were made of gold, silver, bronze, tin; they were decorated by inserts of multicolored enamel or glass, filigree, carving and engraving. The majority of the surviving items are reliquaries. A notable example of jewel art is the eighth-century reliquary that was found in Rannaghan—it has images of the Savior in a tunic, angels and martyred soldiers, whose garments are covered with intricate ornaments.

Almost all of the Christian churches in Ireland in the first millennium A.D. were wooden (mainly oak, a short-lived material). No traces of those buildings have survived to this day, and we can above all judge the country’s early Christian architecture by book miniatures. These were “rectangular buildings with protruding corner beams, a high, gabled double-pitched roof with a carved ridge… Beams were placed vertically.”9 The altar in such churches was separated from the nave, with partitions separating the male and the female parts of the church space. Doors and doorways were adorned with carvings, walls and partitions were covered with sacred images and ornaments. The earliest records of stone churches (of which none are preserved) go back to the eighth century. Such temples were a rare exception at that time. Why stone buildings appeared so late on the island (which is replete with stone, though, unlike Russia, has a scarcity of forests) is unknown. There have been various attempts to explain this phenomenon.

“Some researchers conjecture that the pre-Christian oak worship and the reverence to the first wooden churches originally founded by saints were revealed in this way.”10

In the late eighth century, Ireland, like continental Europe, suffered a disaster that continued for several centuries and changed the course of its history radically. These were raids of the Norsemen. In 794, Vikings ravaged settlements on small islands between Britain and Ireland. During those assaults Irish monasteries were looted and their monks massacred. Those forays were followed by new plundering raids by Scandinavians who would disembark from their longships on the coast. In the early ninth century, the Norsemen would attack the settlements of Eire from the shores, and later would move upstream on their drakkars further inland, where they would murder people, steal treasures, burn the local dwellings, churches, monastic and buildings, and take locals captive or enslave them. Assaults were made once a year. The Irish tried to resist and indeed managed to beat off some attacks, but in most cases they suffered defeats from the aggressive and ruthless invaders. Besides, their political fragmentation made the nation very vulnerable. Describing the situation in Ireland in the early ninth century, a chronicler from Ulster wrote:

“There was no bay, no harbor, no fortification, no shelter, no burgh that was not flooded with Vikings or pirates.”11

Having consolidated their positions on the coast, Vikings settled and overwintered there. Later their settlements appeared further inland, or at a distance that could be covered in a day and then deep inland. Now the threat of annihilation and enslavement was a real danger to the Gaels of Ireland—something that the Britons had gone through several centuries before [at the hands of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.—Ed.] and had only managed to retain independence in the west of their motherland—in Wales.

The political and national catastrophe that had befallen Ireland didn’t strangle it spiritually. Its missionaries’ religious zeal of didn’t fade away, and the country continued to produce saints.