Describing the Indescribable

PHOTO GALLERY

To one nun iconographer, St. Justin (Popović) wrote:

“I wish for you, my child, enlightenment and illumination from the Lord, so you might learn as best as possible the art of imprinting the unspeakable beauty of the face of the Lord in paint. Indescribable, He allowed Himself to be described, taking on a human body. He—the ‘Unapproachable Light’—came down to us, to become accessible to us men, through ‘the veil of the flesh.’ The holy art of iconography is to express this in paint.”

How can this great and holy art be learned? How can we describe the Indescribable? The iconographer sisters of the St. Alexander Nevsky-Novo Tikhvin Monastery in Ekaterinburg tell about their experience.

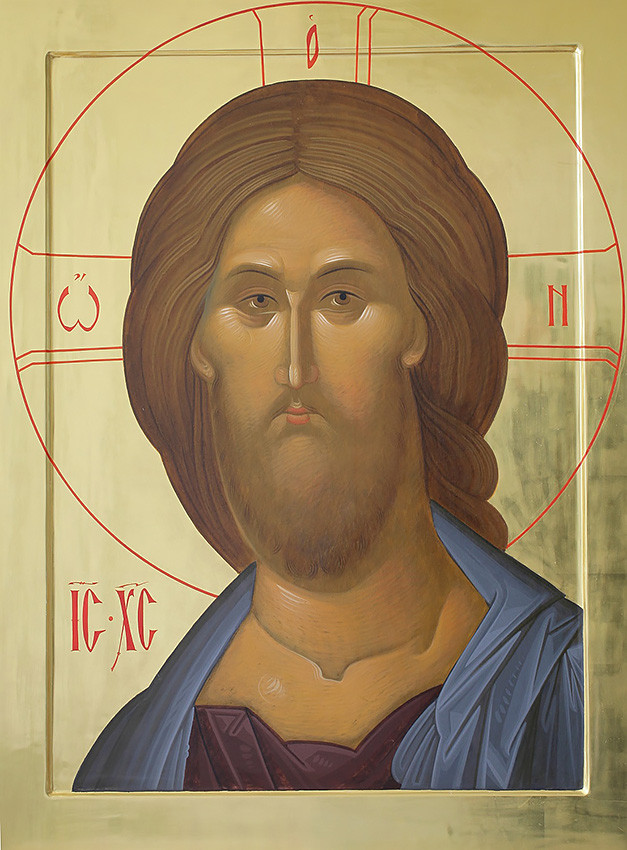

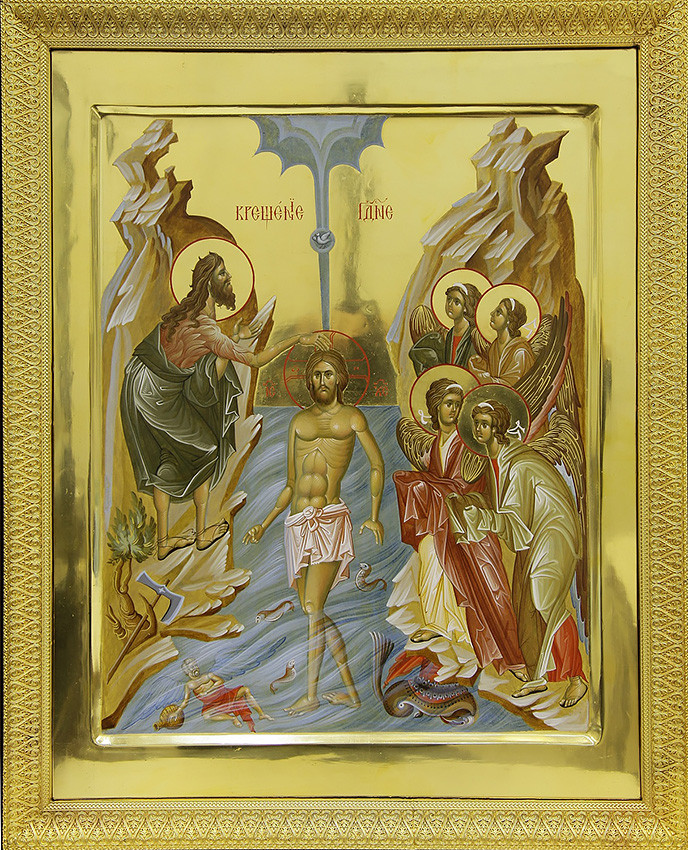

The highest beauty cannot be adequately conveyed by ordinary artistic means—it requires special means of representation and special symbolism. The iconographic language has been developed by the Church for centuries. The monastery has chosen Byzantine icons of the Palaiologian period (second half of the 13th century-first half of the 14th century) and ancient Russian icons of the 13th-15th centuries as role models. This period was the apogee of icon painting.

When you look at a canonically-painted icon, where every detail has its spiritual meaning, then, even without knowing the exact meaning of every symbol, you get the feeling that the depicted countenances and events are “not of this world.” Such icons are truly theology in colors.

During their trips to the ancient churches of Greece, Serbia, and Macedonia, where the best examples of Byzantine iconography of the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries have been preserved, the sisters carefully study the frescoes of Byzantine masters and their students: the composition, color scheme, and image details.

The sisters spend hours carefully copying the icons painted by ancient masters in these churches.

Thanks to this work, they learn the unique iconographic language.

“For us, it’s important to learn not just to copy ancient icons, but to create new images using the techniques we have learned,” says Mother Anna, who bears obedience in the iconography workshop.

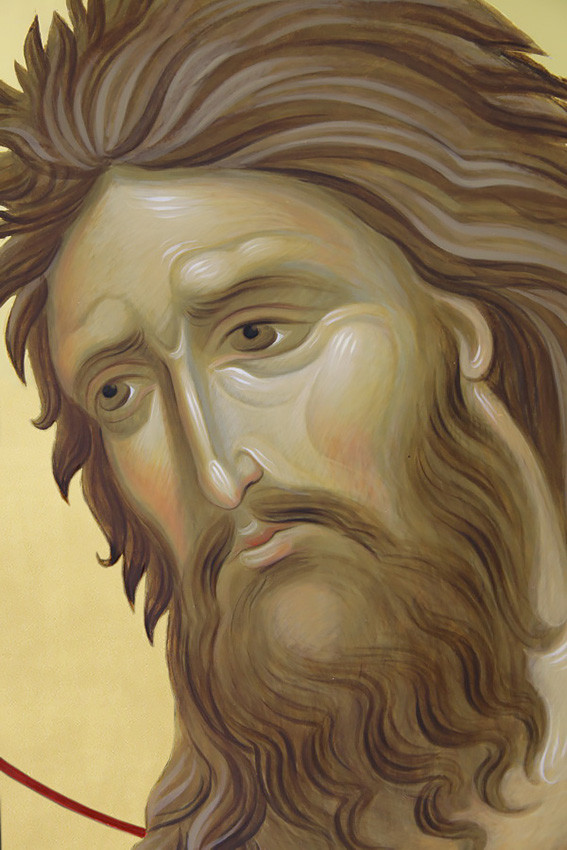

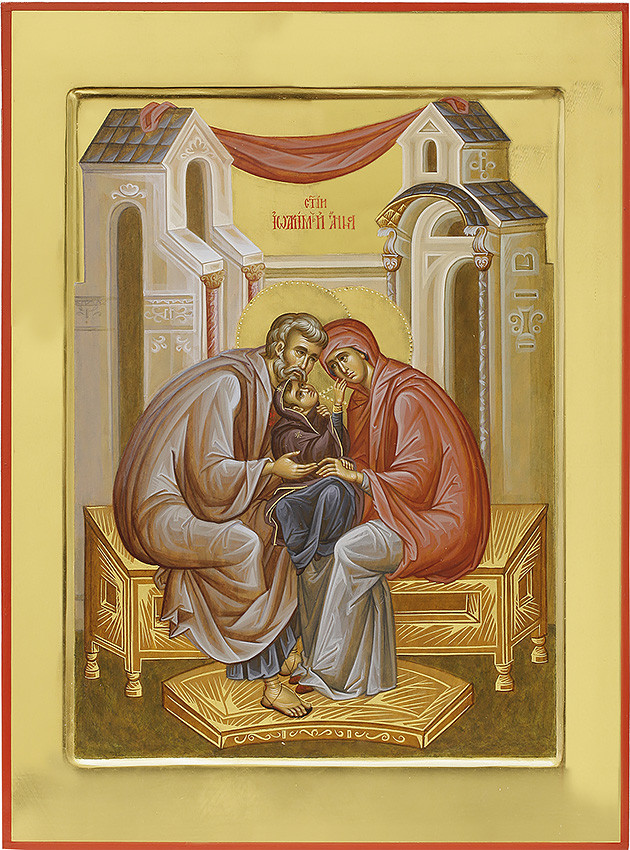

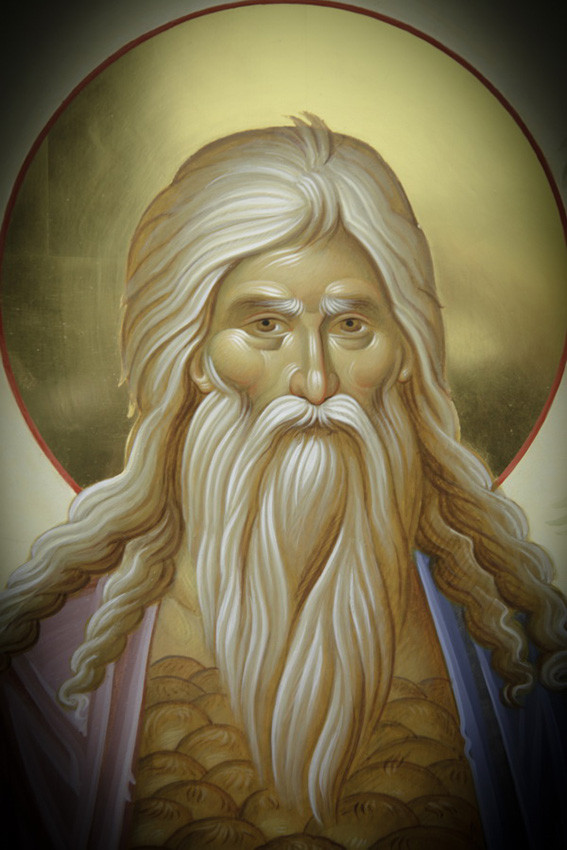

“The most striking thing for us about Byzantine icons is the freedom with which they are painted. We work so hard just to copy an icon with all its details. But the ancient masters painted as freely as you speak your native language. Their skill is amazing: How subtly they applied colors, how skillfully they made the brushstrokes, how well they knew anatomy, such that icons perfectly show both cheekbones and brow ridges—their faces are alive, not conventional. You can look at them forever and admire some lock of hair that accidentally got away from the saint, or the touching, purely infant-like gesture of the little Most Holy Theotokos sitting in the arms of her parents. The figures in icons are not static, but truly alive, very emotional.

“It can be compared with studying a foreign language. First you have to learn letters, then words and grammar, then how to build phrases and read texts in the foreign language. And gradually, if you study a lot, you will learn to speak the language fluently, so that you yourself can write new texts. It’s the same with the iconographic language. To learn to speak it freely, we have to copy and study a lot and comprehend all the details.

“Our iconographer nuns were engaged in the same work—the study and copying of ancient icons—in the Tretyakov Gallery, where they have one of the largest collections of Russian and Byzantine icons in Russia, including icons painted by St. Andrei Rublev.

“Interestingly,” says Mother Anna, “on the icons painted by St. Andrei Rublev, experts couldn’t detect any traces from the brush even with a microscope, unlike the icons of other masters. It’s like his icons weren’t made by hands… How wide was his brush? In what direction did he make his strokes? This remains a secret of the saintly master.”

The sisters turn to experienced specialists for advice. They’ve been talking with art critic and restorer Anna Yegorievna Yakovleva for more than twenty years now. Teachers regularly come to the monastery to hold lectures and practical classes.

Of course, iconographers have to constantly improve their skills of drawing and painting, of plastic anatomy and composition, and the ability to convey the living colors of nature. They regularly work with professional artists. The sisters are especially grateful to the artists Vasily Grigorievich and Lyubov Gennadievna Antsiferov, with whom they’ve been friends for many years.

Specialists also help the sisters solve practical problems—to develop drafts of iconostases and the interiors of churches. For example, the sisters developed the color and tonal layout of the monastery church of the Joy of All Who Sorrow Icon of the Mother of God together with Professor E. N. Maximov.

Work on sacred images is impossible without the advice of a spiritually experienced person. Many of the sisters’ sketches and prepared icons are shown to the monastery’s spiritual father Schema-Archimandrite Abraham, who gave his blessing twenty-five years ago to create an iconography workshop in the monastery. It was Fr. Abraham who immediately set the direction of the workshop—to focus on the best examples of Byzantine and ancient Russian iconography, because they combine high artistic skill and spiritual content, inspiring prayer.

“Icons depict people and events in a slightly different way than we see them in life. Natural proportions are changed and faces are depicted differently than in academic painting. Why? So we would see not only the external side of the event, but, most importantly, its inner essence. Thanks to special iconographic techniques, everything becomes symbolic, meaningful, forcing us to look at things differently” (from a conversation of Fr. Abraham with the sisters).

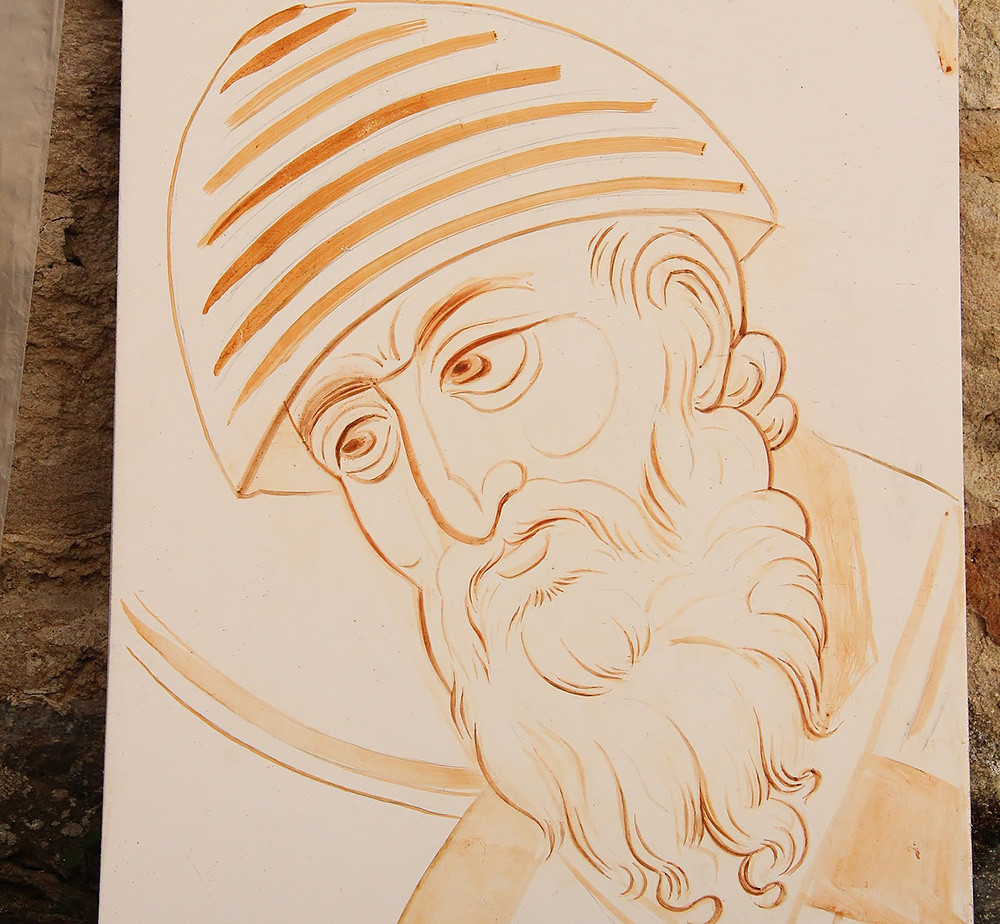

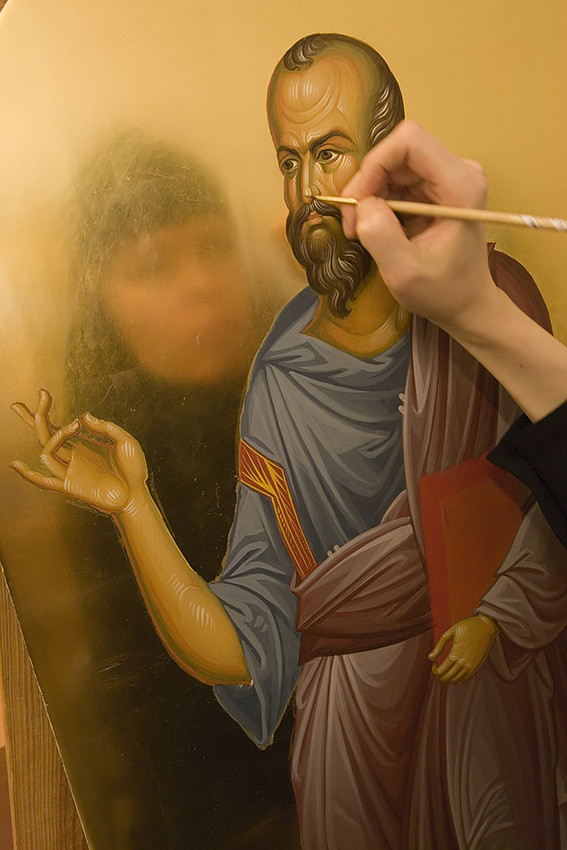

Several sisters are involved in the work on each icon: One applies the primer, another makes the drawing, and a third applies the gold.

The workshop tries to adhere to the ancient techniques of icon-painting: The paint is applied in a special way, in several layers, in a certain sequence. This is why the images on ancient icons looked spiritualized and penetrated with light.

The most delicate work is, of course, painting the face. The iconographer nuns strive to paint the faces of the Lord, the Mother of God, and the saints so they would be alive and expressive, and strictly canonical.

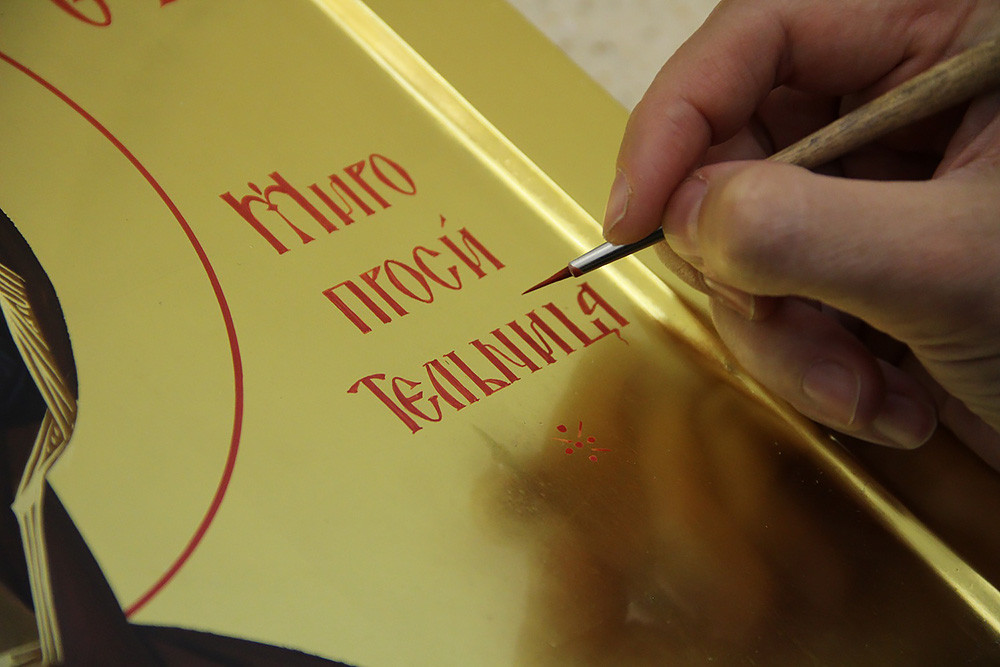

All details should be carefully painted on icons as well: the halo, letters, and medallions.

For more than ten years now, the sisters have been mastering the difficult art of fresco painting. Its difficulty is in that you have to fill a large space with painting, and with very large images (for example, the Savior’s halo in the dome of the monastery cathedral has a diameter of thirteen feet), and in creating multi-figure compositions.

The sisters have painted frescoes in several of the monastery churches.

“The most important thing in the art of iconography is, of course, not technique or paint,” says Mother Anna. “How can we create the image of a holy person? How can an icon convey holy, exalted feelings rather than ordinary human experiences and passions? After all, an icon is made for prayer, and it should inspire and elevate the human spirit. How can we understand or feel how, for example, the Savior should look? What facial expression should the Mother of God have? How can I put this in the icon? For us, as for any iconographer, it’s the most difficult and most important question.”

St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco spoke about it:

“An icon is not a portrait; a portrait depicts only the earthly appearance of a man, but an icon conveys his inner state, his holiness and nearness to Heaven. An icon should display unseen podvigs and shine with Heavenly glory.”

Translated by Jesse Dominick