Aerial view of Breedon-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire--the quary and the church can be seen

Aerial view of Breedon-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire--the quary and the church can be seen

The central counties of England (the Midlands) have a lot to offer. The country’s mid-point is in the village of Fenny Drayton in Leicestershire. The region is famous for the beautiful Peak District national park (Derbyshire and Staffordshire) with hills, moors, the limestone plateau and caves; Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire, famous for the Robin Hood legends; the “Black Country” area, centered around Birmingham with its industrial heritage; the National Forest project to plant an extensive forest in parts of Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, which has been going since the 1990s. Stradford-on-Avon in Warwickshire was the home of the literary genius William Shakespeare; Kenilworth Castle in the same county is the subject of Walter Scott's novel Kenilworth; and Newstead Abbey house in Nottinghamshire was the ancestral home of Lord Byron. You will find castles, Elizabethan mansions and country homes, parks and gardens, rolling fields, canals and rivers, rural English architecture and pretty medieval towns here. Leicestershire has been renowned for its production of world-famous cheeses; the West Midlands—for the school of Pre-Raphaelite artists; Derbyshire—for numerous natural springs... Eyam, the village associated with the Black Death, lies within the region, as does the home of the only native English monastic order of the Gilbertines (in Sempringham, Lincolnshire).

Christianity may have reached central England with the Romans in the first century A.D. After the Anglo-Saxon invasion, the Midlands was dominated by the Saxon kingdom of Mercia (“people of the borders”), the largest of the seven early English kingdoms. The first well-known Mercian king was the infamous Penda, who crops up in many of our articles since he was responsible for the martyrdom of several Christian rulers of other kingdoms. Mercia reached its zenith in the eighth century under the powerful Kings Aethelbald and Offa, who ruled for eighty years altogether. Its decline began as a result of Viking raids in the early ninth century and it had been divided into English and Danish areas by the end of that century. In the tenth century, Mercia was controlled by ealdormen of Wessex, with the Kings of Wessex effectively ruling the whole of England.

Such illustrious early saints as Bertram of Ilam, Chad of Lichfield, Edith of Polesworth, Paulinus of York1 and Werburgh of Chester labored in this region; Sts. Alcmund, Rumwold and Wistan were venerated here posthumously; and St. Wilfrid of York reposed in the town of Oundle2. Central England is home to such ancient ecclesiastical centers as Coventry, Derby, Leicester, Lichfield, Repton, Southwell, Stafford and Tamworth. There are some fine Saxon churches, numerous holy wells with unique histories, caves where hermits used to live, and even places associated with appearances of the Mother of God. Among modern masterpieces, St. Giles Catholic Church in Cheadle, Staffordshire, by the architect Augustus Pugin, is worth mentioning. Let’s talk about several locally venerated saints of central England.

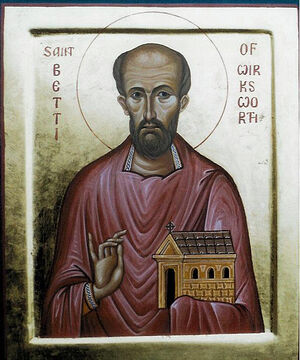

Saint Betti of Wirksworth

An icon of St. Betti of Wirksworth, by Aidan Hart (kindly provided by Canon David Truby) The only author to mention this obscure saint is the Venerable Bede, who in his History of the English Church and People wrote that in 653 four priests named Adda, Betti, Cedd and Diuma were sent from Northumbria to preach the Gospel in Mercia, serving as the first missionaries in this land, previously a bastion of paganism. They came with the newly-baptized young Prince Peada of Mercia3 (a son of Penda), who soon would become the first Christian ruler of this kingdom. Alas, Peada’s reign was very brief: he was treacherously murdered on Pascha in 656—according to one version, at the instigation of his wife, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria. Nothing is known of what became of Adda; St. Cedd was soon called back to Northumbria and later travelled to the kingdom of Essex, which he enlightened; St. Diuma was consecrated the first bishop of the Mercians and the Middle Angles, though he reposed a few years later. And St. Betti, according to a late tradition, founded a church in what is now the attractive town of Wirksworth in Derbyshire, on the edge of the Peak District, and evangelized the neighboring areas. Recently his veneration among some Orthodox has been revived, and his icon painted.

An icon of St. Betti of Wirksworth, by Aidan Hart (kindly provided by Canon David Truby) The only author to mention this obscure saint is the Venerable Bede, who in his History of the English Church and People wrote that in 653 four priests named Adda, Betti, Cedd and Diuma were sent from Northumbria to preach the Gospel in Mercia, serving as the first missionaries in this land, previously a bastion of paganism. They came with the newly-baptized young Prince Peada of Mercia3 (a son of Penda), who soon would become the first Christian ruler of this kingdom. Alas, Peada’s reign was very brief: he was treacherously murdered on Pascha in 656—according to one version, at the instigation of his wife, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria. Nothing is known of what became of Adda; St. Cedd was soon called back to Northumbria and later travelled to the kingdom of Essex, which he enlightened; St. Diuma was consecrated the first bishop of the Mercians and the Middle Angles, though he reposed a few years later. And St. Betti, according to a late tradition, founded a church in what is now the attractive town of Wirksworth in Derbyshire, on the edge of the Peak District, and evangelized the neighboring areas. Recently his veneration among some Orthodox has been revived, and his icon painted.

St. Mary's Church in Wirksworth, Derbyshire (kindly provided by Canon David Truby)

St. Mary's Church in Wirksworth, Derbyshire (kindly provided by Canon David Truby)

Today St. Betti is remembered in the magnificent Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Wirksworth. During the nineteenth-century restoration works, an Anglo-Saxon coffin lid was discovered under its chancel area—it has been known as the “Wirksworth stone” ever since. The lid is oblong and measures five by three feet, though originally it was larger. It dates back to the late seventh century and is decorated with religious scenes. The lid was on top of a stone coffin with the well-preserved skeleton of a tall individual inside it. The coffin was closed after some archeological research, and the lid was placed into the north wall of the church. Though there is no solid evidence, it is possible that St. Betti who died in the second half of the seventh century was buried in this tomb. The chancel is in a very prominent place worthy of the church founder, and the decorations on the lid are fitting for such an important figure. The subsequent research of the remains supported the idea that the skeleton may belong to a Saxon-era priest. Obviously, it was buried under the chancel floor to save it from Henry VIII’s commissioners.

The supposed St. Betti's coffin lid at St. Mary's Church in Wirksworth, Derbyshire (kindly provided by the 'Message Machine' Company through Canon David Truby)

The supposed St. Betti's coffin lid at St. Mary's Church in Wirksworth, Derbyshire (kindly provided by the 'Message Machine' Company through Canon David Truby)

The lid has some of the best surviving Anglo-Saxon carvings. They depict scenes from the life of Christ and the Apostles. In the top row, you can see the Savior washing the disciples’ feet; the crucified Lamb of God (symbolizing Christ); the Dormition and burial of the Mother of God; and the Presentation of the Infant Christ in the Temple. In the lower row, there are the scenes of the Harrowing of Hell; the Ascension of the Lord; the Annunciation; and the Mother of God holding her Divine Child, Who holds the scroll in one hand and points to St. Peter with the other. Though they are only slightly younger than St. Betti himself, the carvings look as if they were created yesterday! No wonder they are described in the book England’s Thousand Best Churches by the author Simon Jenkins (b. 1943), who testifies that the figures “radiate life.” This set of carvings illustrates the closeness of the theology of that age to Orthodoxy, especially in respect to the role of the Mother of God in our salvation. The precious elaborate lid is now kept in the nave.

There are a number of other carvings on the church walls, depicting both Biblical and non-Biblical events, dating back to the Saxon and medieval periods, along with fragments of early stone crosses, grave slabs, etc. Among the most interesting features are the scene of the serpent and Adam near the “Wirksworth stone,” and the figure of a miner in the south transept symbolizing the town’s lead mining industry. All these are rare survivals, since church art works were destroyed throughout the country under Henry VIII and Oliver Cromwell.

The first church on this site was founded in the 650s, and the current structure, in the Early English and Perpendicular Gothic styles, dates back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It was restored by the architect George Gilbert Scott in the 1870s and again more recently. Among its other points are stained glass windows by a Pre-Raphaelite artist, numerous memorials, the interesting Holy Rood Chapel and, quite unusually, two baptismal fonts. It deserves to be called one of the finest churches in Derbyshire.

Outside the church there is a medieval preaching cross shaft in a circular churchyard (an indicator of a pre-Norman origin) on an earlier base which may have been Saxon. The first such cross on this site was probably erected by St. Betti.

It is believed that the town’s origin is connected with local warm thermal water springs. The Wirksworth community preserves some old customs, such as the annual “dressing” (decorating) of the wells and “clipping the church” (in this case: close to the Nativity of the Mother of God), when the whole congregation encircles the church by holding each one’s hands, often followed by cheering, dancing, singing hymns or a sermon. The church has musical traditions and often serves as a venue for concerts. There are references to Wirksworth in the novels The Mill on the Floss and Adam Bede by George Eliot.

Saint Hardulph of Breedon-on-the-Hill

Commemorated August 6/19 and August 21/September 3

The story of St. Hardulph (Hardulf) is another story of an obscure saint venerated in a splendid Midland church. This time it is the Priory Church of St. Mary and St. Hardulph in the village of Breedon-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire—the only church to bear his name, though he was also venerated at St. Oswald’s Augustinian Priory of Nostell in West Yorkshire. According to the most popular tradition, St. Hardulph lived in the second half of the seventh century as a hermit in an ancient cave-dwelling near Ingleby in south Derbyshire, and possibly as a monk at the monastery at Breedon-on-the-Hill five miles away just over the Leicestershire border, where he was buried. A hermit with the name Hardulph is mentioned in the twelfth-century Life of St. Modwenna of Burton-on-Trent, who lived at the same time. But there is an alternative version--that our saint was named Eardwulf and was an early ninth century King of Northumbria (c. 796–c. 806) who was exiled to Mercia during the dynastic strife and ended his days there as an ascetic.

The Anchor Caves near Ingleby, Derbs (by Colin Park, Geograph.org.uk)

The Anchor Caves near Ingleby, Derbs (by Colin Park, Geograph.org.uk)

Near the hamlet of Ingleby, a network of connected ancient caves cut out of soft sandstone rocks—and still in solitude—attracted many early hermits. Apart from Hardulph, the name of the medieval Monk Bernard is known. The caves are dotted along the cliffs within a distance of around 100 yards and are collectively called the “Anchor Church.” Centuries ago they were skillfully adapted for human living: with the roof, the floor, doors, windows, rooms and a chapel. Until recently, modern scientists believed these caves to be eighteenth-century “follies” (decorative buildings designed to enhance the natural landscape), but according to the latest findings of the Royal Agricultural University’s Cultural Heritage Institute, Wessex Archeology, and the University of Bristol’s Speleological Society, they date back to the early Middle Ages—perhaps to the ninth century, making them the oldest surviving Saxon domestic interiors in existence.4 St. Hardulph may have created the first crude hermitage in the Anchor Cave for himself, but there were obvious later alterations, since the pillars look Gothic (too early for his time) and there were attempts to create a vaulted ceiling. Sadly, graffiti is another one of the more recent additions.

According to a medieval document, Hardulph lived as a recluse in a cell in a cliff by the River Trent (which has since changed its course) and once saved two nuns—sent to take the book that he had forgotten to bring to St. Modwenna5—from drowning.

Replica of the Saxon angel's carving at the Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Hardulph in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (provided by Rachel Askew)

Replica of the Saxon angel's carving at the Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Hardulph in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (provided by Rachel Askew)

As for Breedon-on-the-Hill, the resting place of St. Hardulph, this settlement is a puzzle. The first part of its name, “Bre”, means “hill” in Old Welsh, and “dun” too means “hill” in Old English. This elevated place in an otherwise flat area must have been considered holy from the pre-Christian period and was used as a fortress in the Iron Age. It is believed that the evangelization of what is now Leicestershire began from there. Breedon-on-the-Hill Monastery was reputedly founded by the holy King Ethelred of Mercia and dependent on the larger Peterborough Abbey in Cambridgeshire (then in Mercia). The name of the first abbot of Breedon was Hedda (who later served as Bishop of Lichfield), and St. Hardulph may have been its second abbot, though there is not enough evidence to confirm this. At least our saint was buried at the monastery church and has been held in special esteem here ever since. Some scholars suggest that St. Hardulph came to the new establishment in Breedon from Cambridgeshire to preach and teach here and even taught St. Modwenna the monastic life, but again there is lack of evidence to confirm this theory. There is even the version that Breedon Monastery appeared on the site of St. Hardulph’s hermitage. In any case, St. Hardulph is above all venerated by modern Orthodox as a hermit of holy life. The conversion of Mercia started a generation before St. Hardulph, and while there were missionaries, bishops, abbots, abbesses and priests, the eremitic movement was extremely popular.

Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Hardulph in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (provided by Martin Vaughan through Rachel Askew)

Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Hardulph in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (provided by Martin Vaughan through Rachel Askew)

Breedon Monastery gained fame as a great center of monastic life, culture, crafts and learning in the “Age of Saints.” It is no wonder that St. Tatwine, the future tenth archbishop of Canterbury (731–734; feast: July 30), in his young years was a priest-monk at this monastery and maybe even a disciple of St. Hardulph. Known for his piety and erudition, St. Tatwine composed a Latin grammar book and a collection of riddles, which have both survives. He was esteemed by St. Bede, who wrote: “In the year of our Lord's Incarnation 731, Archbishop Bertwald died of old age... In his stead Tatwine, of the province of the Mercians, was made archbishop, having been a priest in the monastery called Briudun [Breedon]. He was consecrated in the city of Canterbury…, being a man renowned for religion and wisdom, and notably learned in Sacred Writ” (b. V, ch. XXXII).

There was a list of saints’ relics that were housed at the Breedon Priory Church’s crypt (which may be buried under the floor east of the altar). These saints are Beonna (probably Abbot of Peterborough till 805), Monk Cotta (nothing is known of him), and Frithuric (a Mercian nobleman who endowed Breedon Monastery in about 676, though he is mentioned as a martyr in an Exeter litany). Breedon was a popular pilgrimage destination. Since bones from both sexes have been found in a cemetery by the church, it is suggested that Breedon was a double monastery.

One of the Saxon carvings at the church in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (taken from Leicestershirechurches.co.uk)

One of the Saxon carvings at the church in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (taken from Leicestershirechurches.co.uk)

The church of Breedon has the largest collection of Anglian art in existence, including relief sculptures on panels, carvings, bands of frieze (on religious and secular motives), and fragments of stone crosses, dating to the eighth and ninth centuries. The surviving stone structure with panels representing processions of robed and bearded figures might have been an outer part of St. Hardulph’s Saxon shrine.

The Saxon figure believed to represent the Mother of God at the Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Hardulph in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (provided by Rachel Askew)

The Saxon figure believed to represent the Mother of God at the Priory Church of Sts. Mary and Hardulph in Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics (provided by Rachel Askew)

The cowled figure of a mysterious woman holding a Gospel book and giving a blessing is thought by experts to represent the Mother of God, but this is open to debate. Another famous robed figure represents “the Breedon angel,” who also offers a blessing. Currently large-scale restoration works are going on in the church, which is why the original angel carving is inaccessible and was replaced by a replica. The latest research of the original shows that it could be the Archangel Gabriel. You will see saints, various human figures, warriors, vine, birds, beasts, hunting, ornaments and patterns on your “”Saxon” tour around the church. Many experts see Byzantine, partly Mediterranean, Celtic, Saxon and Danish influences in these enigmatic artworks. Be that as it may, all of them demonstrate that Breedon was a very important Christian center. These unique carvings, the message of which is not always easy to understand, are displayed throughout the church. All these masterpieces created in the Saxon era were preserved by the post-Conquest Catholic monks and rescued during the Dissolution. Many of them ended up built into the church’s south porch, but since 1937 they have all been kept inside the church (those in the south aisle are encased to protect them from damp).

The church sits within an Iron Age hill ford on top of a limestone hill 400 feet high, with a working quarry below it (several counties can be seen in a clear day). It consists of a sanctuary, a nave, the north and the south aisles with the Lady Chapel and a tower. The monastery of Breedon was mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Later it suffered at the hands of the Vikings (probably in 874, when they sacked nearby Repton), but during the reign of St. Edgar the Peaceable the monastery was restored or refounded by St. Ethelwold of Winchester. In 1122, it was re-established as an Augustinian priory, which depended on the aforementioned Nostell Monastery. The present church is largely the chancel of the pre-Dissolution monastery church. It was purchased by the wealthy Shirley family for their burial at the time of the Reformation, and the villagers petitioned for it to be spared, so the edifice stands to this day, while the claustral buildings were demolished.

In the early twentieth century, the church still organized pilgrimages to Ingleby’s Anchor Caves. At present, they are visited in private by Orthodox Christians or by small groups.

There is St. Hardulph’s Church of England Primary School in Breedon-on-the-Hill. The nearest town to this village is Ashby-de-la-Zouch. Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned in its castle in 1569.

Venerable Modwenna of Burton-on-Trent

Commemorated July 5/18

St. Modwenna's image on the altar frontal of St. Modwen's Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (kindly provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate) If there was an early Life of this saint—the holy virgin Modwenna (Modwen) of Burton—it was sadly lost. All we have is two biographies from the twelfth century and other late documents, which are full of inconsistencies. According to those legends, St. Modwenna was of Irish origin, was a missionary, died in Scotland and was buried in England, and her relics were claimed by the English, the Irish and the Scottish. Some even say that there were two or more saints with this name. However, if we rely on the more reliable tradition that persists in the Midlands, the English St. Modwenna was a holy maiden and ascetic of the seventh century, who founded or was an abbess of the Mercian Polesworth Monastery in what is now Warwickshire (or Trensall in Staffordshire, according to another version) on the land given by a Mercian king and later lived as an anchoress on the small island of Andresey (in honor of the Apostle Andrew) in the River Trent near the present-day Staffordshire town of Burton-on-Trent, where she was buried and became famous for miracles. She may have enlightened the area around Burton and founded one or more churches here. The monastery called Burton Abbey6 was founded near her hermitage to perpetuate her feats. The town of Burton-on-Trent grew around it. Her memory is still alive in this county.

St. Modwenna's image on the altar frontal of St. Modwen's Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (kindly provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate) If there was an early Life of this saint—the holy virgin Modwenna (Modwen) of Burton—it was sadly lost. All we have is two biographies from the twelfth century and other late documents, which are full of inconsistencies. According to those legends, St. Modwenna was of Irish origin, was a missionary, died in Scotland and was buried in England, and her relics were claimed by the English, the Irish and the Scottish. Some even say that there were two or more saints with this name. However, if we rely on the more reliable tradition that persists in the Midlands, the English St. Modwenna was a holy maiden and ascetic of the seventh century, who founded or was an abbess of the Mercian Polesworth Monastery in what is now Warwickshire (or Trensall in Staffordshire, according to another version) on the land given by a Mercian king and later lived as an anchoress on the small island of Andresey (in honor of the Apostle Andrew) in the River Trent near the present-day Staffordshire town of Burton-on-Trent, where she was buried and became famous for miracles. She may have enlightened the area around Burton and founded one or more churches here. The monastery called Burton Abbey6 was founded near her hermitage to perpetuate her feats. The town of Burton-on-Trent grew around it. Her memory is still alive in this county.

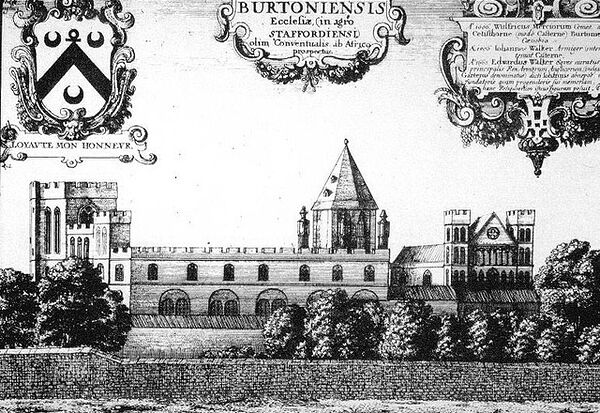

An old print of Burton Abbey, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate)

An old print of Burton Abbey, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate)

At first St. Modwenna was buried on Andresey, where a memorial chapel was mentioned from the early thirteenth century onwards (first dedicated to St. Andrew, then to St. Modwenna). Then her holy remains were translated to the Abbey Church of Burton-on-Trent, where they were visited by pilgrims. Her first precious shrine was despoiled under Abbot Leofric shortly before the Norman Conquest and her body was later enshrined again and placed behind the choir near the altar. There was another translation in the twelfth century, followed by new miracles. Many monarchs, beginning with William I, visited Burton Abbey and St. Modwenna’s relics. A new shrine was made in the fifteenth century. There was a famous statue of St. Modwenna with her tame red cow and St. Modwenna’s staff (women strove to lean upon or walk with it as it relieved labor pains). Alas, all these relics were destroyed during the Reformation. Though the veneration of saints was prohibited, girls in Burton continued to be named “Modwen” after the Reformation. In the Middle Ages, her fame spread to the monasteries of Winchester and Reading, and parts of her relics were kept in Canterbury and Salisbury Cathedrals. One of numerous medieval fairs in Burton was held on St. Modwenna’s feast-day. She is usually depicted as an abbess with a cow by her side.

Inside St. Modwen's Anglican Church in Burton-on-Trent (provided by St. Modwen's parish)

Inside St. Modwen's Anglican Church in Burton-on-Trent (provided by St. Modwen's parish)

Interior of St. Modwen's Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate)

Interior of St. Modwen's Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate)

The market town of Burton-on-Trent has a population of 70 000 and is known for its breweries. It is in eastern Staffordshire next to the Derbyshire border. It is home to the two churches in the world dedicated to St. Modwenna: the Anglican St. Modwen’s Church and the Catholic St. Mary and St. Modwen’s Church. The Catholic church has a set of stained-glass windows depicting scenes from our saint’s life. Built in the late 1870s in the neo-Gothic style, it is richly embellished with murals inside and has statues of the Mother of God and St. Modwenna in canopied niches outside. Though the Anglican church has no windows representing St. Modwenna, it does have an altar frontal showing her, and a (liturgical) cope with “Celtic” images connected with her medieval biography, including her swans, the river, and the sea of glass like unto crystal (Rev. 4:6). The alabaster panel in the church, apart from our saint, depicts the Savior, Sts. Peter, Chad and Martha.

Sts. Mary and Modwen's RC Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (taken from Churches-uk-ireland.org)

Sts. Mary and Modwen's RC Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (taken from Churches-uk-ireland.org)

The parish celebrates a patronal feast every year on the Sunday nearest to July 5 (the saint’s feast according to the old calendar). The church stands on the site of the Benedictine abbey, which was closed under Henry VIII: part of the former abbey church was then used as a parish church, demolished around 1718 and replaced by the present structure. In some sense this church is the successor of the abbey: it was finished in 1728. Built of red sandstone, this imposing town center church dominates the market square. It is built in the classical style and comprises a nave with five bays and galleries on three sides, an apse, a narthex, a tower, a porch, with the sanctuary and the Lady Chapel. One of the few survivors from the old abbey in this church is a fifteenth-century font.

St. Modwen's Anglican Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (provided by St. Modwen's parish)

St. Modwen's Anglican Church in Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (provided by St. Modwen's parish)

The Catholic primary school in Burton bears the name of St. Modwenna. Burton Bridge was the scene of a battle during the English Civil War, when the Royalists captured the town in 1643. Burton was the birthplace of Robert Sutton, who in 1588 was executed under Elizabeth I in Stafford just for being a Catholic priest.

In addition to the churches, Burton and the surroundings have some other sites worth visiting to remember the legacy of the holy abbess and anchoress. Firstly, the minor ruins of Burdon Monastery are visible in the grounds of the riverside Winery bar and restaurant. I’ll say a few words about its history. The earliest monastery in Burton appeared in the seventh or eighth centuries. It was refounded in 1003 by the wealthy nobleman Wulfric, who became its patron and was buried in its cloisters. That monastery was dedicated to St. Benedict of Nursia and All Saints. After the Norman Conquest, a Catholic Benedictine abbey appeared on its site: a community of monks dedicated first to St. Mary and later to St. Mary and St. Modwen. The veneration of this saint was so great that Burton was once called “Mudwennestow,” meaning “Modwenna’s holy place.”

The monastery church was divided into the “upper” church for monks and the “lower” one for the townsfolk. The monastery occupied a huge area of fourteen acres and was the center of the town’s life. The monastery church had chapels dedicated to St. Mary (with Her statue), St. Edmund, St. Nicholas, the Apostles, the Martyrs, the Confessors. Subsequently there was even a guild attached to the monastery. At one time, it was the poorest of England’s monasteries, yet at another time—the most important monastery in Staffordshire (Blithbury Priory in Staffordshire was dependent on it). The Annals of Burton Abbey were written at the monastery in the thirteenth century and cover its history between 1004 and 1263. It was dissolved in 1539, though it functioned as a college of Christ and the Virgin Mary for a dean and several prebendaries for a few years afterwards. Only some arches from the chapter house and a cloister wall can be found in a garden. St. Modwenna’s Anglican Church sits close by.

St. Modwenna's statue, Andresey, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (photo - Wikimedia Commons) Secondly, Andresey Island where the saint lived as an anchoress is connected with the town by two bridges. St. Modwenna chose St. Andrew the First-Called as her heavenly patron and had her hermitage chapel and a holy well dedicated to him. Nothing remains of her cell, but the well still exists: it is located between the two bridges by the river and is fenced off to prevent it from desecration and disturbance by animals. It was famous for healings (scrofula and other diseases). Pilgrims used to bring generous offerings to give thanks for their healing. The chapel was also a pilgrimage destination and had its own keeper.

St. Modwenna's statue, Andresey, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (photo - Wikimedia Commons) Secondly, Andresey Island where the saint lived as an anchoress is connected with the town by two bridges. St. Modwenna chose St. Andrew the First-Called as her heavenly patron and had her hermitage chapel and a holy well dedicated to him. Nothing remains of her cell, but the well still exists: it is located between the two bridges by the river and is fenced off to prevent it from desecration and disturbance by animals. It was famous for healings (scrofula and other diseases). Pilgrims used to bring generous offerings to give thanks for their healing. The chapel was also a pilgrimage destination and had its own keeper.

Though the veneration of holy wells was suppressed under Henry VIII, St. Modwenna’s Well was still used by believers in the eighteenth century with reports of miracles. Andresey Island also has a contemporary monument to our saint, the holy foundress and patroness of this town. The small Cherry Orchard marks the site of the first (wooden) chapel, which housed her relics, before they were translated to the monastery church. A stone chapel was later erected on its site (the original one was desecrated by the Danes in the fateful year 874) to commemorate the saint’s memory: it stood here for centuries, but no traces of it survive.

St. Peter's Church in Stapenhill, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (Photo from Burton-on-trent.org.uk)

St. Peter's Church in Stapenhill, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs (Photo from Burton-on-trent.org.uk)

Thirdly, there is the nineteenth-century St. Peter’s church in Stapenhill, a suburb of Burton, sitting at the foot of a hill on the site where St. Modwenna founded one of her churches in the area. The original church had Sts. Peter and Paul as its patrons and may have had minster status before the Conquest. Some of its stained-glass windows represent Sts. Alban, Chad and Modwenna.

Stained glass image of St. Modwenna at Hamstall Ridware church, Staffs (kindly provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate) Outside Burton, there used to be an altar in honor of St. Modwenna in the thirteenth century St. Oswald’s Church in Ashbourne, Derbyshire. This church preserves a fragment of medieval glass thought to show St. Modwenna (head only). The Church of St. Michael and All Angels in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, has a medieval stained-glass window which may represent St. Modwenna. The ancient Pillaton Hall near Penkridge, Staffordshire, which belonged to the landowning Littleton family, had a chapel dedicated to St. Modwenna. Now the house is partly ruined and partly reconstructed, and the chapel was restored in 1880 and is still in use. Centuries ago, a chapel was dedicated to our saint in the parish church of Offchurch in Warwickshire.

Stained glass image of St. Modwenna at Hamstall Ridware church, Staffs (kindly provided by St. Modwen's Assistant Curate) Outside Burton, there used to be an altar in honor of St. Modwenna in the thirteenth century St. Oswald’s Church in Ashbourne, Derbyshire. This church preserves a fragment of medieval glass thought to show St. Modwenna (head only). The Church of St. Michael and All Angels in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, has a medieval stained-glass window which may represent St. Modwenna. The ancient Pillaton Hall near Penkridge, Staffordshire, which belonged to the landowning Littleton family, had a chapel dedicated to St. Modwenna. Now the house is partly ruined and partly reconstructed, and the chapel was restored in 1880 and is still in use. Centuries ago, a chapel was dedicated to our saint in the parish church of Offchurch in Warwickshire.